§ 5.

Now we must guard against the grave misunderstanding of supposing that, because perception is brought about through knowledge of causality, the relation of cause and effect exists between object and subject. On the contrary, this relation always occurs only between immediate and mediate object, and hence always only between objects. On this false assumption rests the foolish controversy about the reality of the external world, a controversy in which dogmatism and scepticism oppose each other, and the former appears now as realism, now as idealism. Realism posits the object as cause, and places its effect in the subject. The idealism of Fichte makes the object the effect of the subject. Since, however—and this cannot be sufficiently stressed—absolutely no relation according to the principle of sufficient reason subsists between subject and object, neither of these two assertions could ever be proved, and scepticism made triumphant attacks on both. Now just as the law of causality already precedes, as condition, perception and experience, and thus cannot be learnt from these (as Hume imagined), so object and subject precede all knowledge, and hence even the principle of sufficient reason in general, as the first condition. For this principle is only the form of every object, the whole nature and manner of its appearance; but the object always presupposes the subject, and hence between the two there can be no relation of reason and consequent. My essay On the Principle of Sufficient Reason purports to achieve just this: it explains the content of that principle as the essential form of every object, in other words, as the universal mode and manner of all objective existence, as something which pertains to the object as such. But the object as such everywhere presupposes the subject as its necessary correlative, and hence the subject always remains outside the province of the validity of the principle of sufficient reason. The controversy about the reality of the external world rests precisely on this false extension of the validity of the principle of sufficient reason to the subject also, and, starting from this misunderstanding, it could never understand itself. On the one hand, realistic dogmatism, regarding the representation as the effect of the object, tries to separate these two, representation and object, which are but one, and to assume a cause quite different from the representation, an object-in-itself independent of the subject, something that is wholly inconceivable; for as object it presupposes the subject, and thus always remains only the representation of the subject. Opposed to this is scepticism, with the same false assumption that in the representation we always have only the effect, never the cause, and so never real being; that we always know only the action of objects. But this, it supposes, might have no resemblance whatever to that being, and would indeed generally be quite falsely assumed, for the law of causality is first accepted from experience, and then the reality of experience is in turn supposed to rest on it. Both these views are open to the correction, firstly, that object and representation are the same thing; that the true being of objects of perception is their action; that the actuality of the thing consists exactly in this; and that the demand for the existence of the object outside the representation of the subject, and also for a real being of the actual thing distinct from its action, has no meaning at all, and is a contradiction. Therefore knowledge of the nature of the effect of a perceived object exhausts the object itself in so far as it is object, i.e., representation, as beyond this there is nothing left in it for knowledge. To this extent, therefore, the perceived world in space and time, proclaiming itself as nothing but causality, is perfectly real, and is absolutely what it appears to be; it appears wholly and without reserve as representation, hanging together according to the law of causality. This is its empirical reality. On the other hand, all causality is only in the understanding and for the understanding. The entire actual, i.e., active, world is therefore always conditioned as such by the understanding, and without this is nothing. Not for this reason only, but also because in general no object without subject can be conceived without involving a contradiction, we must absolutely deny to the dogmatist the reality of the external world, when he declares this to be its independence of the subject. The whole world of objects is and remains representation, and is for this reason wholly and for ever conditioned by the subject; in other words, it has transcendental ideality. But it is not on that account falsehood or illusion; it presents itself as what it is, as representation, and indeed as a series of representations, whose common bond is the principle of sufficient reason. As such it is intelligible to the healthy understanding, even according to its innermost meaning, and to the understanding it speaks a perfectly clear language. To dispute about its reality can occur only to a mind perverted by oversubtle sophistry; such disputing always occurs through an incorrect application of the principle of sufficient reason. This principle combines all representations, of whatever kind they be, one with another; but it in no way connects these with the subject, or with something that is neither subject nor object but only the ground of the object; an absurdity, since only objects can be the ground of objects, and that indeed always. If we examine the source of this question about the reality of the external world more closely, we find that, besides the false application of the principle of sufficient reason to what lies outside its province, there is in addition a special confusion of its forms. Thus that form, which the principle of sufficient reason has merely in reference to concepts or abstract representations, is extended to representations of perception, to real objects, and a ground of knowing is demanded of objects that can have no other ground than one of becoming. Over the abstract representations, the concepts connected to judgements, the principle of sufficient reason certainly rules in such a way that each of these has its worth, its validity, its whole existence, here called truth, simply and solely through the relation of the judgement to something outside it, to its ground of knowledge, to which therefore there must always be a return. On the other hand, over real objects, the representations of perception, the principle of sufficient reason rules as the principle not of the ground of knowing, but of becoming, as the law of causality. Each of them has paid its debt to it by having become, in other words, by having appeared as effect from a cause. Therefore a demand for a ground of knowledge has no validity and no meaning here, but belongs to quite another class of objects. Thus the world of perception raises no question or doubt in the observer, so long as he remains in contact with it. Here there is neither error nor truth, for these are confined to the province of the abstract, of reflection. But here the world lies open to the senses and to the understanding; it presents itself with naïve truth as that which it is, as representation of perception that is developed in the bonds of the law of causality.

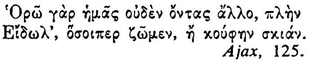

So far as we have considered the question of the reality of the external world, it always arose from a confusion, amounting even to a misunderstanding, of the faculty of reason itself, and to this extent the question could be answered only by explaining its subject-matter. After an examination of the whole nature of the principle of sufficient reason, of the relation between object and subject, and of the real character of sense-perception, the question itself was bound to disappear, because there was no longer any meaning in it. But this question has yet another origin, quite different from the purely speculative one so far mentioned, a really empirical origin, although the question is always raised from a speculative point of view, and in this form has a much more comprehensible meaning than it had in the former. We have dreams; may not the whole of life be a dream? or more exactly: is there a sure criterion for distinguishing between dream and reality, between phantasms and real objects? The plea that what is dreamt has less vividness and distinctness than real perception has, is not worth considering at all, for no one has held the two up to comparison; only the recollection of the dream could be compared with the present reality. Kant answers the question as follows: “The connexion of the representations among themselves according to the law of causality distinguishes life from the dream.” But even in the dream every single thing is connected according to the principle of sufficient reason in all its forms, and this connexion is broken only between life and the dream and between individual dreams. Kant’s answer might therefore run as follows: the long dream (life) has complete connexion in itself according to the principle of sufficient reason; but it has no such connexion with the short dreams, although each of these has within itself the same connexion; thus the bridge between the former and the latter is broken, and on this account the two are distinguished. To institute an inquiry in accordance with this criterion as to whether something was dreamt or really took place would, however, be very difficult, and often impossible. For we are by no means in a position to follow link by link the causal connexion between any experienced event and the present moment; yet we do not on that account declare that it is dreamt. Therefore in real life we do not usually make use of that method of investigation to distinguish between dream and reality. The only certain criterion for distinguishing dream from reality is in fact none other than the wholly empirical one of waking, by which the causal connexion between the dreamed events and those of waking life is at any rate positively and palpably broken off. An excellent proof of this is given by the remark, made by Hobbes in the second chapter of Leviathan, that we easily mistake dreams for reality when we have unintentionally fallen asleep in our clothes, and particularly when it happens that some undertaking or scheme occupies all our thoughts, and engrosses our attention in our dreams as well as in our waking moments. In these cases, the waking is almost as little observed as is the falling asleep; dream and reality flow into one another and become confused. Then, of course, only the application of Kant’s criterion is left. If subsequently, as is often the case, the causal connexion with the present, or the absence of such connexion, cannot possibly be ascertained, then it must remain for ever undecided whether an event was dreamt or whether it really occurred. Here indeed the close relationship between life and the dream is brought out for us very clearly. We will not be ashamed to confess it, after it has been recognized and expressed by many great men. The Vedas and Puranas know no better simile for the whole knowledge of the actual world, called by them the web of Mâyâ, than the dream, and they use none more frequently. Plato often says that men live only in the dream; only the philosopher strives to be awake. Pindar says (Pyth. viii, 135): σϰιᾶς ὄναρ ἄνθρωπoς (umbrae somnium homo),18 and Sophocles:

(Nos enim, quicunque vivimus, nihil aliud esse comperio, quam simulacra et levem umbram.) 19 Beside which Shakespeare stands most worthily:

“We are such stuff

As dreams are made on, and our little life

Is rounded with a sleep.”

The Tempest, Act IV, Sc. 1.

Finally, Calderón was so deeply impressed with this view, that he sought to express it in a kind of metaphysical drama, Life a Dream (‘La Vida es Sueno’).

After these numerous passages from the poets, I may now be permitted to express myself by a metaphor. Life and dreams are leaves of one and the same book. The systematic reading is real life, but when the actual reading hour (the day) has come to an end, and we have the period of recreation, we often continue idly to thumb over the leaves, and turn to a page here and there without method or connexion. We sometimes turn up a page we have already read, at others one still unknown to us, but always from the same book. Such an isolated page is, of course, not connected with a consistent reading and study of the book, yet it is not so very inferior thereto, if we note that the whole of the consistent perusal begins and ends also on the spur of the moment, and can therefore be regarded merely as a larger single page.

Thus, although individual dreams are marked off from real life by the fact that they do not fit into the continuity of experience that runs constantly through life, and waking up indicates this difference, yet that very continuity of experience belongs to real life as its form, and the dream can likewise point to a continuity in itself. Now if we assume a standpoint of judgement external to both, we find no distinct difference in their nature, and are forced to concede to the poets that life is a long dream.

To return from this entirely independent empirical origin of the question of the reality of the external world to its speculative origin, we have found that this lay firstly in the false application of the principle of sufficient reason, namely between subject and object, and then again in the confusion of its forms, since the principle of sufficient reason of knowing was extended to the province where the principle of sufficient reason of becoming is valid. Yet this question could hardly have occupied philosophers so continuously, if it were entirely without any real content, and if some genuine thought and meaning did not lie at its very core as its real source. Accordingly, from this it would have to be assumed that, first by entering reflection and seeking its expression, it became involved in those confused and incomprehensible forms and questions. This is certainly my opinion, and I reckon that the pure expression of that innermost meaning of the question which it was unable to arrive at, is this: What is this world of perception besides being my representation? Is that of which I am conscious only as representation just the same as my own body, of which I am doubly conscious, on the one hand as representation, on the other as will? The clearer explanation of this question, and its answer in the affirmative, will be the content of the second book, and the conclusions from it will occupy the remaining part of this work.