§ 20.

As the being-in-itself of our own body, as that which this body is besides being object of perception, namely representation, the will, as we have said, proclaims itself first of all in the voluntary movements of this body, in so far as these movements are nothing but the visibility of the individual acts of the will. These movements appear directly and simultaneously with those acts of will; they are one and the same thing with them, and are distinguished from them only by the form of perceptibility into which they have passed, that is to say, in which they have become representation.

But these acts of the will always have a ground or reason outside themselves in motives. Yet these motives never determine more than what I will at this time, in this place, in these circumstances, not that I will in general, or what I will in general, in other words, the maxim characterizing the whole of my willing. Therefore, the whole inner nature of my willing cannot be explained from the motives, but they determine merely its manifestation at a given point of time; they are merely the occasion on which my will shows itself. This will itself, on the other hand, lies outside the province of the law of motivation; only the phenomenon of the will at each point of time is determined by this law. Only on the presupposition of my empirical character is the motive a sufficient ground of explanation of my conduct. But if I abstract from my character, and then ask why in general I will this and not that, no answer is possible, because only the appearance or phenomenon of the will is subject to the principle of sufficient reason, not the will itself, which in this respect may be called groundless. Here I in part presuppose Kant’s doctrine of the empirical and intelligible characters, as well as my remarks pertinent to this in the Grundprobleme der Ethik, pp. 48-58, and again p. 178 seqq. of the first edition (pp. 46-57 and 174 seqq. of the second). We shall have to speak about this again in more detail in the fourth book. For the present, I have only to draw attention to the fact that one phenomenon being established by another, as in this case the deed by the motive, does not in the least conflict with the essence-in-itself of the deed being will. The will itself has no ground; the principle of sufficient reason in all its aspects is merely the form of knowledge, and hence its validity extends only to the representation, to the phenomenon, to the visibility of the will, not to the will itself that becomes visible.

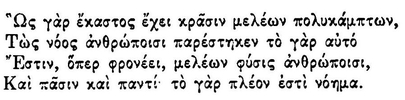

Now if every action of my body is an appearance or phenomenon of an act of will in which my will itself in general and as a whole, and hence my character, again expresses itself under given motives, then phenomenon or appearance of the will must also be the indispensable condition and presupposition of every action. For the will’s appearance cannot depend on something which does not exist directly and only through it, and would therefore be merely accidental for it, whereby the will’s appearance itself would be only accidental. But that condition is the whole body itself. Therefore this body itself must be phenomenon of the will, and must be related to my will as a whole, that is to say, to my intelligible character, the phenomenon of which in time is my empirical character, in the same way as the particular action of the body is to the particular act of the will. Therefore the whole body must be nothing but my will become visible, must be my will itself, in so far as this is object of perception, representation of the first class. It has already been advanced in confirmation of this that every impression on my body also affects my will at once and immediately, and in this respect is called pain or pleasure, or in a lower degree, pleasant or unpleasant sensation. Conversely, it has also been advanced that every violent movement of the will, and hence every emotion and passion, convulses the body, and disturbs the course of its functions. Indeed an etiological, though very incomplete, account can be given of the origin of my body, and a somewhat better account of its development and preservation. Indeed this is physiology; but this explains its theme only in exactly the same way as motives explain action. Therefore the establishment of the individual action through the motive, and the necessary sequence of the action from the motive, do not conflict with the fact that action, in general and by its nature, is only phenomenon or appearance of a will that is in itself groundless. Just as little does the physiological explanation of the functions of the body detract from the philosophical truth that the whole existence of this body and the sum-total of its functions are only the objectification of that will which appears in this body’s outward actions in accordance with motives. If, however, physiology tries to refer even these outward actions, the immediate voluntary movements, to causes in the organism, for example, to explain the movement of a muscle from an affluxion of humours (“like the contraction of a cord that is wet,” as Reil says in the Archiv für Physiologie, Vol. VI, p. 153); supposing that it really did come to a thorough explanation of this kind, this would never do away with the immediately certain truth that every voluntary movement (functiones animales) is phenomenon of an act of will. Now, just as little can the physiological explanation of vegetative life (functiones naturales, vitales), however far it may be developed, ever do away with the truth that this whole animal life, thus developing itself, is phenomenon of the will. Generally then, as already stated, no etiological explanation can ever state more than the necessarily determined position in time and space of a particular phenomenon and its necessary appearance there according to a fixed rule. On the other hand, the inner nature of everything that appears in this way remains for ever unfathomable, and is presupposed by every etiological explanation; it is merely expressed by the name force, or law of nature, or, when we speak of actions, the name character or will. Thus, although every particular action, under the presupposition of the definite character, necessarily ensues with the presented motive, and although growth, the process of nourishment, and all the changes in the animal body take place according to necessarily acting causes (stimuli), the whole series of actions, and consequently every individual act and likewise its condition, namely the whole body itself which performs it, and therefore also the process through which and in which the body exists, are nothing but the phenomenal appearance of the will, its becoming visible, the objectivity of the will. On this rests the perfect suitability of the human and animal body to the human and animal will in general, resembling, but far surpassing, the suitability of a purposely made instrument to the will of its maker, and on this account appearing as fitness or appropriateness, i.e., the teleological accountability of the body. Therefore the parts of the body must correspond completely to the chief demands and desires by which the will manifests itself; they must be the visible expression of these desires. Teeth, gullet, and intestinal canal are objectified hunger; the genitals are objectified sexual impulse; grasping hands and nimble feet correspond to the more indirect strivings of the will which they represent. Just as the general human form corresponds to the general human will, so to the individually modified will, namely the character of the individual, there corresponds the individual bodily structure, which is therefore as a whole and in all its parts characteristic and full of expression. It is very remarkable that even Parmenides expressed this in the following verses, quoted by Aristotle (Metaphysics, iii, 5):

(Ut enim cuique complexio membrorum flexibilium se habet, ita mens hominibus adest: idem namque est, quod sapit, membrorum natura hominibus, et omnibus et omni: quod enim plus est, intelligentia est.)58