§ 51.

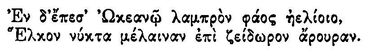

If with the foregoing observations on art in general we turn from the plastic and pictorial arts to poetry, we shall have no doubt that its aim is also to reveal the Ideas, the grades of the will’s objectification, and to communicate them to the hearer with that distinctness and vividness in which they were apprehended by the poetical mind. Ideas are essentially perceptive; therefore, if in poetry only abstract concepts are directly communicated by words, yet it is obviously the intention to let the hearer perceive the Ideas of life in the representatives of these concepts; and this can take place only by the assistance of his own imagination. But in order to set this imagination in motion in accordance with the end in view, the abstract concepts that are the direct material of poetry, as of the driest prose, must be so arranged that their spheres intersect one another, so that none can continue in its abstract universality, but instead of it a perceptive representative appears before the imagination, and this is then modified further and further by the words of the poet according to his intention. Just as the chemist obtains solid precipitates by combining perfectly clear and transparent fluids, so does the poet know how to precipitate, as it were, the concrete, the individual, the representation of perception, out of the abstract, transparent universality of the concepts by the way in which he combines them. For the Idea can be known only through perception, but knowledge of the Idea is the aim of all art. The skill of a master in poetry as in chemistry enables one always to obtain the precise precipitate that was intended. The many epithets in poetry serve this purpose, and through them the universality of every concept is restricted more and more till perceptibility is reached. To almost every noun Homer adds an adjective, the concept of which cuts, and at once considerably diminishes, the sphere of the first concept, whereby it is brought so very much nearer to perception; for example:

(Occidit vero in Oceanum splendidum lumen solis,

Trahens noctem nigram super alman terra.)119

And

“Where gentle breezes from the blue heavens sigh,

There stands the myrtle still, the laurel high,”

[Goethe, Mignon]

precipitates from a few concepts before the imagination the delight of the southern climate.

Rhythm and rhyme are quite special aids to poetry. I can give no other explanation of their incredibly powerful effect than that our powers of representation have received from time, to which they are essentially bound, some special characteristic, by virtue of which we inwardly follow and, as it were, consent to each regularly recurring sound. In this way rhythm and rhyme become a means partly of holding our attention, since we more willingly follow the poem when read; and partly through them there arises in us a blind consent to what is read, prior to any judgement, and this gives the poem a certain emphatic power of conviction, independent of all reason or argument.

In virtue of the universality of the material, and hence of the concepts of which poetry makes use to communicate the Ideas, the range of its province is very great. The whole of nature, the Ideas of all grades, can be expressed by it, since it proceeds, according to the Idea to be communicated, to express these sometimes in a descriptive, sometimes in a narrative, and sometimes in a directly dramatic way. But if, in the presentation of the lower grades of the will’s objectivity, plastic and pictorial art often surpasses poetry, because inanimate, and also merely animal, nature reveals almost the whole of its inner being in a single well-conceived moment; man, on the other hand, in so far as he expresses himself not through the mere form and expression of his features and countenance, but through a chain of actions and of the accompanying thoughts and emotions, is the principal subject of poetry. In this respect no other art can compete with poetry, for it has the benefit of progress and movement which the plastic and pictorial arts lack.

Revelation of that Idea which is the highest grade of the will’s objectivity, namely the presentation of man in the connected series of his efforts and actions, is thus the great subject of poetry. It is true that experience and history teach us to know man, yet more often men rather than man; in other words, they give us empirical notes about the behaviour of men towards one another. From these we obtain rules for our own conduct rather than a deep insight into the inner nature of man. This latter, however, is by no means ruled out; yet, whenever the inner nature of mankind itself is disclosed to us in history or in our own experience, we have apprehended this experience poetically, and the historian has apprehended history with artistic eyes, in other words, according to the Idea, not to the phenomenon; according to its inner nature, not to the relations. Our own experience is the indispensable condition for understanding poetry as well as history, for it is, so to speak, the dictionary of the language spoken by both. But history is related to poetry as portrait-painting to historical painting; the former gives us the true in the individual, the latter the true in the universal; the former has the truth of the phenomenon and can verify it therefrom; the latter has the truth of the Idea, to be found in no particular phenomenon, yet speaking from them all. The poet from deliberate choice presents us with significant characters in significant situations; the historian takes both as they come. In fact, he has to regard and select the events and persons not according to their inner genuine significance expressing the Idea, but according to the outward, apparent, and relatively important significance in reference to the connexion and to the consequences. He cannot consider anything in and by itself according to its essential character and expression, but must look at everything according to its relation, its concatenation, its influence on what follows, and especially on its own times. Therefore he will not pass over a king’s action, in itself quite common and of little significance, for it has consequences and influence. On the other hand, extremely significant actions of very distinguished individuals are not to be mentioned by him if they have no consequences and no influence. For his considerations proceed in accordance with the principle of sufficient reason, and apprehend the phenomenon of which this principle is the form. The poet, however, apprehends the Idea, the inner being of mankind outside all relation and all time, the adequate objectivity of the thing-in-itself at its highest grade. Even in that method of treatment necessary to the historian, the inner nature, the significance of phenomena, the kernel of all those shells, can never be entirely lost, and can still be found and recognized by the person who looks for it. Yet that which is significant in itself, not in the relation, namely the real unfolding of the Idea, is found to be far more accurate and clear in poetry than in history; therefore, paradoxical as it may sound, far more real, genuine, inner truth is to be attributed to poetry than to history. For the historian should accurately follow the individual event according to life as this event is developed in time in the manifold tortuous and complicated chains of reasons or grounds and consequents. But he cannot possibly possess all the data for this; he cannot have seen all and ascertained everything. At every moment he is forsaken by the original of his picture, or a false picture is substituted for it; and this happens so frequently, that I think I can assume that in all history the false outweighs the true. On the other hand, the poet has apprehended the Idea of mankind from some definite side to be described; thus it is the nature of his own self that is objectified in it for him. His knowledge, as was said above in connexion with sculpture, is half a priori; his ideal is before his mind, firm, clear, brightly illuminated, and it cannot forsake him. He therefore shows us in the mirror of his mind the Idea purely and distinctly, and his description down to the last detail is as true as life itself.120 The great ancient historians are therefore poets in the particulars where data forsake them, e.g., in the speeches of their heroes; indeed, the whole way in which they handle their material approaches the epic. But this gives their presentations unity, and enables them to retain inner truth, even where outer truth was not accessible to them, or was in fact falsified. If just now we compared history to portrait-painting, in contrast to poetry that corresponded to historical painting, we find Winckelmann’s maxim, that the portrait should be the ideal of the individual, also followed by the ancient historians, for they depict the individual in such a way that the side of the Idea of mankind expressed in it makes its appearance. On the other hand, modern historians, with few exceptions, generally give us only “an offal-barrel and a lumber-garret, or at the best a Punch-and-Judy play.” 121 Therefore, he who seeks to know mankind according to its inner nature which is identical in all its phenomena and developments, and thus according to its Idea, will find that the works of the great, immortal poets present him with a much truer and clearer picture than the historians can ever give. For even the best of them are as poets far from being the first, and also their hands are not free. In this respect we can illustrate the relation between historian and poet by the following comparison. The mere, pure historian, working only according to data, is like a man who, without any knowledge of mathematics, investigates by measurement the proportions of figures previously found by accident, and therefore the statement of these measurements found empirically is subject to all the errors of the figure as drawn. The poet, on the contrary, is like the mathematician who constructs these ratios a priori in pure intuition or perception, and expresses them not as they actually are in the drawn figure, but as they are in the Idea that the drawing is supposed to render perceptible. Therefore Schiller [An die Freunde] says:

“What has never anywhere come to pass,

That alone never grows old.”

In regard to knowledge of the inner nature of mankind, I must concede a greater value to biographies, and particularly to autobiographies, than to history proper, at any rate to history as it is usually treated. This is partly because, in the former, the data can be brought together more accurately and completely than in the latter; partly because, in history proper, it is not so much men that act as nations and armies, and the individuals who do appear seem to be so far off, surrounded by such pomp and circumstance, clothed in the stiff robes of State, or in heavy and inflexible armour, that it is really very difficult to recognize human movement through it all. On the other hand, the truly depicted life of the individual in a narrow sphere shows the conduct of men in all its nuances and forms, the excellence, the virtue, and even the holiness of individuals, the perversity, meanness, and malice of most, the profligacy of many. Indeed, from the point of view we are here considering, namely in regard to the inner significance of what appears, it is quite immaterial whether the objects on which the action hinges are, relatively considered, trifling or important, farmhouses or kingdoms. For all these things are without significance in themselves, and obtain it only in so far as the will is moved by them. The motive has significance merely through its relation to the will; on the other hand, the relation that it has as a thing to other such things does not concern us at all. Just as a circle of one inch in diameter and one of forty million miles in diameter have absolutely the same geometrical properties, so the events and the history of a village and of a kingdom are essentially the same; and we can study and learn to know mankind just as well in the one as in the other. It is also wrong to suppose that autobiographies are full of deceit and dissimulation; on the contrary, lying, though possible everywhere, is perhaps more difficult there than anywhere else. Dissimulation is easiest in mere conversation; indeed, paradoxical as it may sound, it is fundamentally more difficult in a letter, since here a man, left to his own devices, looks into himself and not outwards. The strange and remote are with difficulty brought near to him, and he does not have before his eyes the measure of the impression made on another. The other person, on the contrary, peruses the letter calmly, in a mood that is foreign to the writer, reads it repeatedly and at different times, and thus easily finds out the concealed intention. We also get to know an author as a man most easily from his book, since all those conditions have there an even stronger and more lasting effect; and in an autobiography it is so difficult to dissimulate, that there is perhaps not a single one that is not on the whole truer than any history ever written. The man who records his life surveys it as a whole; the individual thing becomes small, the near becomes distant, the distant again becomes near, motives shrink and contract. He is sitting at the confessional, and is doing so of his own free will. Here the spirit of lying does not seize him so readily, for there is to be found in every man an inclination to truth which has first to be overcome in the case of every lie, and has here taken up an unusually strong position. The relation between biography and the history of nations can be made clear to perception by the following comparison. History shows us mankind just as a view from a high mountain shows us nature. We see a great deal at a time, wide stretches, great masses, but nothing is distinct or recognizable according to the whole of its real nature. On the other hand, the depicted life of the individual shows us the person, just as we know nature when we walk about among her trees, plants, rocks, and stretches of water. Through landscape-painting, in which the artist lets us see nature through his eyes, the knowledge of her Ideas and the condition of pure, will-less knowing required for this are made easy for us. In the same way, poetry is far superior to history and biography for expressing the Ideas that we are able to seek in both. For here also genius holds up before us the illuminating glass in which everything essential and significant is gathered together and placed in the brightest light; but everything accidental and foreign is eliminated.122

The expression of the Idea of mankind, which devolves on the poet, can now be carried out in such a way that the depicted is also at the same time the depicter. This occurs in lyric poetry, in the song proper, where the poet vividly perceives and describes only his own state; hence through the object, a certain subjectivity is essential to poetry of this kind. Or again, the depicter is entirely different from what is to be depicted, as is the case with all other kinds of poetry. Here the depicter more or less conceals himself behind what is depicted, and finally altogether disappears. In the ballad the depicter still expresses to some extent his own state through the tone and proportion of the whole; therefore, though much more objective than the song, it still has something subjective in it. This fades away more in the idyll, still more in the romance, almost entirely in the epic proper, and finally to the last vestige in the drama, which is the most objective, and in more than one respect the most complete, and also the most difficult, form of poetry. The lyric form is therefore the easiest, and if in other respects art belongs only to the true genius who is so rare, even the man who is on the whole not very eminent can produce a beautiful song, when in fact, through strong excitement from outside, some inspiration enhances his mental powers. For this needs only a vivid perception of his own state at the moment of excitement. This is proved by many single songs written by individuals who have otherwise remained unknown, in particular by the German national songs, of which we have an excellent collection in the Wunderhorn, and also by innumerable love-songs and other popular songs in all languages. For to seize the mood of the moment, and embody it in the song, is the whole achievement of poetry of this kind. Yet in the lyrics of genuine poets is reflected the inner nature of the whole of mankind; and all that millions of past, present, and future human beings have found and will find in the same constantly recurring situations, finds in them its corresponding expression. Since these situations, by constant recurrence, exist as permanently as humanity itself, and always call up the same sensations, the lyrical productions of genuine poets remain true, effective, and fresh for thousands of years. If, however, the poet is the universal man, then all that has ever moved a human heart, and all that human nature produces from itself in any situation, all that dwells and broods in any human breast—all these are his theme and material, and with these all the rest of nature as well. Therefore the poet can just as well sing of voluptuousness as of mysticism, be Anacreon or Angelus Silesius, write tragedies or comedies, express the sublime or the common sentiment, according to his mood and disposition. Accordingly, no one can prescribe to the poet that he should be noble and sublime, moral, pious, Christian, or anything else, still less reproach him for being this and not that. He is the mirror of mankind, and brings to its consciousness what it feels and does.

Now if we consider more closely the nature of the lyric proper, and take as examples exquisite and at the same time pure models, not those in any way approximating to another kind of poetry, such as the ballad, the elegy, the hymn, the epigram, and so on, we shall find that the characteristic nature of the song in the narrowest sense is as follows. It is the subject of the will, in other words, the singer’s own willing, that fills his consciousness, often as a released and satisfied willing (joy), but even more often as an impeded willing (sorrow), always as emotion, passion, an agitated state of mind. Besides this, however, and simultaneously with it, the singer, through the sight of surrounding nature, becomes conscious of himself as the subject of pure, will-less knowing, whose unshakable, blissful peace now appears in contrast to the stress of willing that is always restricted and needy. The feeling of this contrast, this alternate play, is really what is expressed in the whole of the song, and what in general constitutes the lyrical state. In this state pure knowing comes to us, so to speak, in order to deliver us from willing and its stress. We follow, yet only for a few moments; willing, desire, the recollection of our own personal aims, always tears us anew from peaceful contemplation; but yet again and again the next beautiful environment, in which pure, will-less knowledge presents itself to us, entices us away from willing. Therefore in the song and in the lyrical mood, willing (the personal interest of the aims) and pure perception of the environment that presents itself are wonderfully blended with each other. Relations between the two are sought and imagined; the subjective disposition, the affection of the will, imparts its hue to the perceived environment, and this environment again imparts in the reflex its colour to that disposition. The genuine song is the expression or copy of the whole of this mingled and divided state of mind. In order to make clear in examples this abstract analysis of a state that is very far from all abstraction, we can take up any of the immortal songs of Goethe. As specially marked out for this purpose I will recommend only a few; The Shepherd’s Lament, Welcome and Farewell, To the Moon, On the Lake, Autumnal Feelings; further the real songs in the Wunderhorn are excellent examples, especially the one that begins: “O Bremen, I must leave you now.” As a comical and really striking parody of the lyric character, a song by Voss strikes me as remarkable. In it he describes the feelings of a drunken plumber, falling from a tower, who in passing observes that the clock on the tower is at half past eleven, a remark quite foreign to his condition, and hence belonging to will-free knowledge. Whoever shares with me the view expressed of the lyrical state of mind will also admit that this is really the perceptive and poetical knowledge of that principle, which I advanced in my essay On the Principle of Sufficient Reason, and which I have also mentioned in this work, namely that the identity of the subject of knowing with the subject of willing can be called the miracle ϰατ’ ἐξoχήν,123 so that the poetical effect of the song really rests ultimately on the truth of that principle. In the course of life, these two subjects, or in popular language head and heart, grow more and more apart; men are always separating more and more their subjective feeling from their objective knowledge. In the child the two are still fully blended; it hardly knows how to distinguish itself from its surroundings; it is merged into them. In the youth all perception in the first place affects feeling and mood, and even mingles with these, as is very beautifully expressed by Byron:

“I live not in myself, but I become

Portion of that around me; and to me

High mountains are a feeling.”

[Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage, III, lxxii.]

This is why the youth clings so much to the perceptive and outward side of things; this is why he is fit only for lyrical poetry, and only the mature man for dramatic poetry. We can think of the old man as at most an epic poet, like Ossian or Homer, for narration is characteristic of the old.

In the more objective kinds of poetry, especially in the romance, the epic, and the drama, the end, the revelation of the Idea of mankind, is attained especially by two means, namely by true and profound presentation of significant characters, and by the invention of pregnant situations in which they disclose themselves. For it is incumbent on the chemist not only to exhibit purely and genuinely the simple elements and their principal compounds, but also to expose them to the influence of those reagents in which their peculiar properties become clearly and strikingly visible. In just the same way, it is incumbent on the poet not only to present to us significant characters as truly and faithfully as does nature herself, but, so that we may get to know them, he must place them in those situations in which their peculiar qualities are completely unfolded, and in which they are presented distinctly in sharp outline; in situations that are therefore called significant. In real life and in history, situations of this nature are only rarely brought about by chance; they exist there alone, lost and hidden in the mass of insignificant detail. The universal significance of the situations should distinguish the romance, the epic, and the drama from real life just as much as do the arrangement and selection of the significant characters. In both, however, the strictest truth is an indispensable condition of their effect, and want of unity in the characters, contradiction of themselves or of the essential nature of mankind in general, as well as impossibility of the events or improbability amounting almost to impossibility, even though it is only in minor circumstances, offend just as much in poetry as do badly drawn figures, false perspective, or defective lighting in painting. For in both poetry and painting we demand a faithful mirror of life, of mankind, of the world, only rendered clear by the presentation, and made significant by the arrangement. As the purpose of all the arts is merely the expression and presentation of the Ideas, and as their essential difference lies only in what grade of the will’s objectification the Idea is that we are to express, by which again the material of expression is determined, even those arts that are most widely separated can by comparison throw light on one another. For example, to grasp completely the Ideas expressing themselves in water, it is not sufficient to see it in the quiet pond or in the evenly-flowing stream, but those Ideas completely unfold themselves only when the water appears under all circumstances and obstacles. The effect of these on it causes it to manifest completely all its properties. We therefore find it beautiful when it rushes down, roars, and foams, or leaps into the air, or falls in a cataract of spray, or finally, when artificially forced, it springs up as a fountain. Thus, exhibiting itself differently in different circumstances, it always asserts its character faithfully; it is just as natural for it to spirt upwards as to lie in glassy stillness; it is as ready for the one as for the other, as soon as the circumstances appear. Now what the hydraulic engineer achieves in the fluid matter of water, the architect achieves in the rigid matter of stone; and this is just what is achieved by the epic or dramatic poet in the Idea of mankind. The common aim of all the arts is the unfolding and elucidation of the Idea expressing itself in the object of every art, of the will objectifying itself at each grade. The life of man, as often seen in the world of reality, is like the water as seen often in pond and river; but in the epic, the romance, and the tragedy, selected characters are placed in those circumstances in which all their characteristics are unfolded, the depths of the human mind are revealed and become visible in extraordinary and significant actions. Thus poetry objectifies the Idea of man, an Idea which has the peculiarity of expressing itself in highly individual characters.

Tragedy is to be regarded, and is recognized, as the summit of poetic art, both as regards the greatness of the effect and the difficulty of the achievement. For the whole of our discussion, it is very significant and worth noting that the purpose of this highest poetical achievement is the description of the terrible side of life. The unspeakable pain, the wretchedness and misery of mankind, the triumph of wickedness, the scornful mastery of chance, and the irretrievable fall of the just and the innocent are all here presented to us; and here is to be found a significant hint as to the nature of the world and of existence. It is the antagonism of the will with itself which is here most completely unfolded at the highest grade of its objectivity, and which comes into fearful prominence. It becomes visible in the suffering of mankind which is produced partly by chance and error; and these stand forth as the rulers of the world, personified as fate through their insidiousness which appears almost like purpose and intention. In part it proceeds from mankind itself through the self-mortifying efforts of will on the part of individuals, through the wickedness and perversity of most. It is one and the same will, living and appearing in them all, whose phenomena fight with one another and tear one another to pieces. In one individual it appears powerfully, in another more feebly. Here and there it reaches thoughtfulness and is softened more or less by the light of knowledge, until at last in the individual case this knowledge is purified and enhanced by suffering itself. It then reaches the point where the phenomenon, the veil of Maya, no longer deceives it. It sees through the form of the phenomenon, the principium individuationis; the egoism resting on this expires with it. The motives that were previously so powerful now lose their force, and instead of them, the complete knowledge of the real nature of the world, acting as a quieter of the will, produces resignation, the giving up not merely of life, but of the whole will-to-live itself. Thus we see in tragedy the noblest men, after a long conflict and suffering, finally renounce for ever all the pleasures of life and the aims till then pursued so keenly, or cheerfully and willingly give up life itself. Thus the steadfast prince of Calderón, Gretchen in Faust, Hamlet whom his friend Horatio would gladly follow, but who enjoins him to remain for a while in this harsh world and to breathe in pain in order to throw light on Hamlet’s fate and clear his memory; also the Maid of Orleans, the Bride of Messina. They all die purified by suffering, in other words after the will-to-live has already expired in them. In Voltaire’s Mohammed this is actually expressed in the concluding words addressed to Mohammed by the dying Palmira: “The world is for tyrants: live!” On the other hand, the demand for so-called poetic justice rests on an entire misconception of the nature of tragedy, indeed of the nature of the world. It boldly appears in all its dulness in the criticisms that Dr. Samuel Johnson made of individual plays of Shakespeare, since he very naively laments the complete disregard of it; and this disregard certainly exists, for what wrong have the Ophelias, the Desdemonas, and the Cordelias done? But only a dull, insipid, optimistic, Protestant-rationalistic, or really Jewish view of the world will make the demand for poetic justice, and find its own satisfaction in that of the demand. The true sense of the tragedy is the deeper insight that what the hero atones for is not his own particular sins, but original sin, in other words, the guilt of existence itself:

Pues el delito mayor

Del hombre es haber nacido.

(“For man’s greatest offence

Is that he has been born,”)

as Calderón [La Vida es Sueño] frankly expresses it.

I will allow myself only one observation more closely concerning the treatment of tragedy. The presentation of a great misfortune is alone essential to tragedy. But the many different ways in which it is produced by the poet can be brought under three typical characteristics. It can be done through the extraordinary wickedness of a character, touching the extreme bounds of possibility, who becomes the author of the misfortune. Examples of this kind are Richard III, Iago in Othello, Shylock in The Merchant of Venice, Franz Moor, the Phaedra of Euripides, Creon in the Antigone, and others. Again, it can happen through blind fate, i.e., chance or error; a true model of this kind is the King Oedipus of Sophocles, also the Trachiniae; and in general most of the tragedies of the ancients belong to this class. Examples among modern tragedies are Romeo and Juliet, Voltaire’s Tancred, and The Bride of Messina. Finally, the misfortune can be brought about also by the mere attitude of the persons to one another through their relations. Thus there is no need either of a colossal error, or of an unheard-of accident, or even of a character reaching the bounds of human possibility in wickedness, but characters as they usually are in a moral regard in circumstances that frequently occur, are so situated with regard to one another that their position forces them, knowingly and with their eyes open, to do one another the greatest injury, without any one of them being entirely in the wrong. This last kind of tragedy seems to me far preferable to the other two; for it shows us the greatest misfortune not as an exception, not as something brought about by rare circumstances or by monstrous characters, but as something that arises easily and spontaneously out of the actions and characters of men, as something almost essential to them, and in this way it is brought terribly near to us. In the other two kinds of tragedy, we look on the prodigious fate and the frightful wickedness as terrible powers threatening us only from a distance, from which we ourselves might well escape without taking refuge in renunciation. The last kind of tragedy, however, shows us those powers that destroy happiness and life, and in such a way that the path to them is at any moment open even to us. We see the greatest suffering brought about by entanglements whose essence could be assumed even by our own fate, and by actions that perhaps even we might be capable of committing, and so we cannot complain of injustice. Then, shuddering, we feel ourselves already in the midst of hell. In this last kind of tragedy the working out is of the greatest difficulty; for the greatest effect has to be produced in it with the least use of means and occasions for movement, merely by their position and distribution. Therefore even in many of the best tragedies this difficulty is evaded. One play, however, can be mentioned as a perfect model of this kind, a tragedy that in other respects is far surpassed by several others of the same great master; it is Clavigo. To a certain extent Hamlet belongs to this class, if, that is to say, we look merely at his relation to Laërtes and to Ophelia. Wallenstein also has this merit. Faust is entirely of this kind, if we consider merely the event connected with Gretchen and her brother as the main action; also the Cid of Corneille, only that this lacks the tragic conclusion, while, on the other hand, the analogous relation of Max to Thecla has it.124