§ 55.

That the will as such is free, follows already from the fact that, according to our view, it is the thing-in-itself, the content of all phenomena. The phenomenon, on the other hand, we recognize as absolutely subordinate to the principle of sufficient reason in its four forms. As we know that necessity is absolutely identical with consequent from a given ground, and that the two are convertible concepts, all that belongs to the phenomenon, in other words all that is object for the subject that knows as an individual, is on the one hand ground or reason, on the other consequent, and in this last capacity is determined with absolute necessity; thus it cannot be in any respect other than it is. The whole content of nature, the sum-total of her phenomena, is absolutely necessary, and the necessity of every part, every phenomenon, every event, can always be demonstrated, since it must be possible to find the ground or reason on which it depends as consequent. This admits of no exception; it follows from the unrestricted and absolute validity of the principle of sufficient reason. But on the other hand, this same world in all its phenomena is for us objectivity of the will. As the will itself is not phenomenon, not representation or object, but thing-in-itself, it is also not subordinate to the principle of sufficient reason, the form of all object. Thus it is not determined as consequent by a reason or ground, and so it knows no necessity; in other words, it is free. The concept of freedom is therefore really a negative one, since its content is merely the denial of necessity, in other words, the denial of the relation of consequent to its ground according to the principle of sufficient reason. Now here we have before us most clearly the point of unity of that great contrast, namely the union of freedom with necessity, which in recent times has often been discussed, yet never, so far as I know, clearly and adequately. Everything as phenomenon, as object, is absolutely necessary; in itself it is will, and this is perfectly free to all eternity. The phenomenon, the object, is necessarily and unalterably determined in the concatenation of grounds and consequents which cannot have any discontinuity. But the existence of this object in general and the manner of its existing, that is to say, the Idea which reveals itself in it, or in other words its character, is directly phenomenon of the will. Hence, in conformity with the freedom of this will, the object might not exist at all, or might be something originally and essentially quite different. In that case, however, the whole chain of which the object is a link, and which is itself phenomenon of the same will, would also be quite different. But once there and existent, the object has entered the series of grounds and consequents, is always necessarily determined therein, and accordingly cannot either become another thing, i.e., change itself, or withdraw from the series, i.e., vanish. Like every other part of nature, man is objectivity of the will; therefore all that we have said holds good of him also. Just as everything in nature has its forces and qualities that definitely react to a definite impression, and constitute its character, so man also has his character, from which the motives call forth his actions with necessity. In this way of acting his empirical character reveals itself, but in this again is revealed his intelligible character, i.e., the will in itself, of which he is the determined phenomenon. Man, however, is the most complete phenomenon of the will, and, as was shown in the second book, in order to exist, this phenomenon had to be illuminated by so high a degree of knowledge that even a perfectly adequate repetition of the inner nature of the world under the form of the representation became possible in it. This is the apprehension of the Ideas, the pure mirror of the world, as we have come to know them in the third book. Therefore in man the will can reach full self-consciousness, distinct and exhaustive knowledge of its own inner nature, as reflected in the whole world. As we saw in the preceding book, art results from the actual presence and existence of this degree of knowledge. At the end of our whole discussion it will also be seen that, through the same knowledge, an elimination and self-denial of the will in its most perfect phenomenon is possible, by the will’s relating such knowledge to itself. Thus the freedom which in other respects, as belonging to the thing-in-itself, can never show itself in the phenomenon, in such a case appears in this phenomenon; and by abolishing the essential nature at the root of the phenomenon, whilst the phenomenon itself still continues to exist in time, it brings about a contradiction of the phenomenon with itself. In just this way, it exhibits the phenomena of holiness and self-denial. All this, however, will be fully understood only at the end of this book. Meanwhile, all this indicates only in a general way how man is distinguished from all the other phenomena of the will by the fact that freedom, i.e., independence of the principle of sufficient reason, which belongs only to the will as thing-in-itself and contradicts the phenomenon, may yet in his case possibly appear even in the phenomenon, where it is then, however, necessarily exhibited as a contradiction of the phenomenon with itself. In this sense not only the will in itself, but even man can certainly be called free, and can thus be distinguished from all other beings. But how this is to be understood can become clear only through all that follows, and for the present we must wholly disregard it. For in the first place we must beware of making the mistake of thinking that the action of the particular, definite man is not subject to any necessity, in other words that the force of the motive is less certain than the force of the cause, or than the following of the conclusion from the premisses. If we leave aside the above-mentioned case, which, as we have said, relates only to an exception, the freedom of the will as thing-in-itself by no means extends directly to its phenomenon, not even where this reaches the highest grade of visibility, namely in the rational animal with individual character, in other words, the man. This man is never free, although he is the phenomenon of a free will, for he is the already determined phenomenon of this will’s free willing; and since he enters into the form of all objects, the principle of sufficient reason, he develops the unity of that will into a plurality of actions. But since the unity of that will in itself lies outside time, this plurality exhibits itself with the conformity to law of a force of nature. Since, however, it is that free willing which becomes visible in the man and in his whole conduct, and is related to this as the concept to the definition, every particular deed of the man is to be ascribed to the free will, and directly proclaims itself as such to consciousness. Therefore, as we said in the second book, everyone considers himself a priori (i.e., according to his original feeling) free, even in his particular actions, in the sense that in every given case any action is possible to him, and only a posteriori, from experience and reflection thereon, does he recognize that his conduct follows with absolute necessity from the coincidence of the character with the motives. Hence it arises that any coarse and uncultured person, following his feelings, most vigorously defends complete freedom in individual actions, whereas the great thinkers of all ages, and the more profound religious teachings, have denied it. But the person who has come to see clearly that man’s whole inner nature is will, and that man himself is only phenomenon of this will, but that such phenomenon has the principle of sufficient reason as its necessary form, knowable even from the subject, and appearing in this case as the law of motivation; to such a person a doubt as to the inevitability of the deed, when the motive is presented to the given character, seems like doubting that the three angles of a triangle are equal to two right angles. In his Doctrine of Philosophical Necessity, Priestley has very adequately demonstrated the necessity of the individual action. Kant, however, whose merit in this regard is specially great, was the first to demonstrate the coexistence of this necessity with the freedom of the will in itself, i.e., outside the phenomenon, for he established the difference between the intelligible and empirical characters.143 I wholly support this distinction, for the former is the will as thing-in-itself, in so far as it appears in a definite individual in a definite degree, while the latter is this phenomenon itself as it manifests itself in the mode of action according to time, and in the physical structure according to space. To make the relation between the two clear, the best expression is that already used in the introductory essay, namely that the intelligible character of every man is to be regarded as an act of will outside time, and thus indivisible and unalterable. The phenomenon of this act of will, developed and drawn out in time, space, and all the forms of the principle of sufficient reason, is the empirical character as it exhibits itself for experience in the man’s whole manner of action and course of life. The whole tree is only the constantly repeated phenomenon of one and the same impulse that manifests itself most simply in the fibre, and is repeated and easily recognizable in the construction of leaf, stem, branch, and trunk. In the same way, all man’s deeds are only the constantly repeated manifestation, varying somewhat in form, of his intelligible character, and the induction resulting from the sum of these gives us his empirical character. However, I shall not repeat Kant’s masterly exposition here, but shall presuppose that it is already known.

In 1840 I dealt thoroughly and in detail with the important chapter on the freedom of the will, in my crowned prize-essay on this subject. In particular, I exposed the reason for the delusion in consequence of which people imagined they found an empirically given, absolute freedom of the will, and hence a liberum arbitrium indifferentiae ,144 in self-consciousness as a fact thereof; for with great insight the question set for the essay was directed to this very point. I therefore refer the reader to that work, and likewise to para. 10 of the prize-essay On the Basis of Morality, which was published along with it under the title Die Beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik, and I omit the discussion on the necessity of the acts of will which was inserted here in the first edition, and was still incomplete. Instead of this, I will explain the delusion above mentioned in a brief discussion which is presupposed by the nineteenth chapter of our second volume, and which therefore could not be given in the essay above mentioned.

Apart from the fact that the will, as the true thing-in-itself, is something actually original and independent, and that in self-consciousness the feeling of originality and arbitrariness must accompany its acts, though these are already determined; apart from this, there arises the semblance of an empirical freedom of the will (instead of the transcendental freedom which alone is to be attributed to it). Thus there arises the appearance of a freedom of the individual acts from the attitude of the intellect towards the will which is explained, separated out, and subordinated in the nineteenth chapter of the second volume, under No. 3. The intellect gets to know the conclusions of the will only a posteriori and empirically. Accordingly, where a choice is presented to it, it has no datum as to how the will is going to decide. For the intelligible character, by virtue of which with the given motives only one decision is possible, which is accordingly a necessary decision, the intelligible character, I say, does not come into the knowledge of the intellect; the empirical character only is successively known to it through its individual acts. Therefore it seems to the knowing consciousness (intellect) that two opposite decisions are equally possible to the will in a given case. But this is just the same as if we were to say in the case of a vertical pole, thrown off its balance and hesitating which way to fall, that “it can topple over to the right or to the left.” Yet this “can” has only a subjective significance, and really means “in view of the data known to us.” For objectively, the direction of the fall is necessarily determined as soon as the hesitation takes place. Accordingly, the decision of one’s own will is undetermined only for its spectator, one’s own intellect, and therefore only relatively and subjectively, namely for the subject of knowing. In itself and objectively, on the other hand, the decision is at once determined and necessary in the case of every choice presented to it. But this determination enters consciousness only through the ensuing decision. We even have an empirical proof of this when some difficult and important choice lies before us, yet only under a condition that has not yet appeared but is merely awaited, so that for the time being we can do nothing, but must maintain a passive attitude. We then reflect on how we shall decide when the circumstances that allow us freedom of activity and decision have made their appearance. It is often the case that far-seeing, rational deliberation speaks rather in support of one of the resolves, while direct inclination leans rather to the other. As long as we remain passive and under compulsion, the side of reason apparently tries to keep the upper hand, but we see in advance how strongly the other side will draw us when the opportunity for action comes. Till then, we are eagerly concerned to place the motives of the two sides in the clearest light by coolly meditating on the pro et contra, so that each motive can influence the will with all its force when the moment arrives, and so that some mistake on the part of the intellect will not mislead the will into deciding otherwise than it would do if everything exerted an equal influence. This distinct unfolding of the motives on both sides is all that the intellect can do in connexion with the choice. It awaits the real decision just as passively and with the same excited curiosity as it would that of a foreign will. Therefore, from its point of view, both decisions must seem to it equally possible. Now it is just this that is the semblance of the will’s empirical freedom. Of course, the decision enters the sphere of the intellect quite empirically as the final conclusion of the matter. Yet this decision proceeded from the inner nature, the intelligible character, of the individual will in its conflict with given motives, and hence came about with complete necessity. The intellect can do nothing more here than clearly examine the nature of the motives from every point of view. It is unable to determine the will itself, for the will is wholly inaccessible to it, and, as we have seen, is for it inscrutable and impenetrable.

If, under the same conditions, a man could act now in one way, now in another, then in the meantime his will itself would have had to be changed, and thus would have to reside in time, for only in time is change possible. But then either the will would have to be a mere phenomenon, or time would have to be a determination of the thing-in-itself. Accordingly, the dispute as to the freedom of the individual action, as to the liberum arbitrium indifferentiae, really turns on the question whether the will resides in time or not. If, as Kant’s teaching as well as the whole of my system makes necessary, the will as thing-in-itself is outside time and outside every form of the principle of sufficient reason, then not only must the individual act in the same way in the same situation, and not only must every bad deed be the sure guarantee of innumerable others that the individual must do and cannot leave undone, but, as Kant says, if only the empirical character and the motives were completely given, a man’s future actions could be calculated like an eclipse of the sun or moon. Just as nature is consistent, so also is the character; every individual action must come about in accordance with the character, just as every phenomenon comes about in accordance with a law of nature. The cause in the latter case and the motive in the former are only the occasional causes, as was shown in the second book. The will, whose phenomenon is the whole being and life of man, cannot deny itself in the particular case, and the man also will always will in the particular what he wills on the whole.

The maintenance of an empirical freedom of will, a liberum arbitrium indifferentiae, is very closely connected with the assertion that places man’s inner nature in a soul that is originally a knowing, indeed really an abstract thinking entity, and only in consequence thereof a willing entity. Such a view, therefore, regarded the will as of a secondary nature, instead of knowledge, which is really secondary. The will was even regarded as an act of thought, and was identified with the judgement, especially by Descartes and Spinoza. According to this, every man would have become what he is only in consequence of his knowledge. He would come into the world as a moral cipher, would know the things in it, and would then determine to be this or that, to act in this or that way. He could, in consequence of new knowledge, choose a new course of action, and thus become another person. Further, he would then first know a thing to be good, and in consequence will it, instead of first willing it, and in consequence calling it good. According to the whole of my fundamental view, all this is a reversal of the true relation. The will is first and original; knowledge is merely added to it as an instrument belonging to the phenomenon of the will. Therefore every man is what he is through his will, and his character is original, for willing is the basis of his inner being. Through the knowledge added to it, he gets to know in the course of experience what he is; in other words, he becomes acquainted with his character. Therefore he knows himself in consequence of, and in accordance with, the nature of his will, instead of willing in consequence of, and according to, his knowing, as in the old view. According to this view, he need only consider how he would best like to be, and he would be so; this is its freedom of the will. It therefore consists in man’s being his own work in the light of knowledge. I, on the other hand, say that he is his own work prior to all knowledge, and knowledge is merely added to illuminate it. Therefore he cannot decide to be this or that; also he cannot become another person, but he is once for all, and subsequently knows what he is. With those other thinkers, he wills what he knows; with me he knows what he wills.

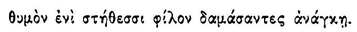

The Greeks called the character ἦθος, and its expressions, i.e., morals, ἦθη. But this word comes from ἔθος, custom; they chose it in order to express metaphorically constancy of character through constancy of custom. Tὸ γὰρ ἦθος ἀπὸ ποῦ ἔθους ἔχει τὴν ἐπωνυμίαν. ἠθιϰὴ γὰρ  διὰ τὸ ἐθίζεσθαι (a voce ἔθος, i.e., consuetudo, ἤθoς est appellatum: ethica ergo dicta est ἀπὸ τοῦ ἐθίζεσθαι, sive ab assuescendo) says Aristotle145 (Ethica Magna, I, 6, p. 1186 [Berlin ed.], and Ethica Eudemica, p. 1220, and Ethica Nicomachaea, p. 1103). Stobaeus, II, chap. 7, quotes: οἱ δὲ ϰατὰ Zήνωνα τροπιϰῶς· ἦθος ὲστι πηγὴ βίου, ἀϕ’ ἧς αἱ ϰατὰ μέρος πράξεις ῥέουσι. (Stoici autem, Zenonis castra sequentes, metaphorice ethos definiunt vitae fontem, e quo singulae manant actiones.)146 In the Christian teaching we find the dogma of predestination in consequence of election and non-election by grace (Rom. ix, 11-24), obviously springing from the view that man does not change, but his life and conduct, in other words his empirical character, are only the unfolding of the intelligible character, the development of decided and unalterable tendencies already recognizable in the child. Therefore his conduct is, so to speak, fixed and settled even at his birth, and remains essentially the same to the very end. We too agree with this, but of course the consequences which resulted from the union of this perfectly correct view with the dogmas previously found in Jewish theology, and which gave rise to the greatest of all difficulties, namely to the eternally insoluble Gordian knot on which most of the controversies of the Church turn; these I do not undertake to defend. For even the Apostle Paul himself scarcely succeeded in doing this by his parable of the potter, invented for this purpose, for ultimately the result was in fact none other than this:

διὰ τὸ ἐθίζεσθαι (a voce ἔθος, i.e., consuetudo, ἤθoς est appellatum: ethica ergo dicta est ἀπὸ τοῦ ἐθίζεσθαι, sive ab assuescendo) says Aristotle145 (Ethica Magna, I, 6, p. 1186 [Berlin ed.], and Ethica Eudemica, p. 1220, and Ethica Nicomachaea, p. 1103). Stobaeus, II, chap. 7, quotes: οἱ δὲ ϰατὰ Zήνωνα τροπιϰῶς· ἦθος ὲστι πηγὴ βίου, ἀϕ’ ἧς αἱ ϰατὰ μέρος πράξεις ῥέουσι. (Stoici autem, Zenonis castra sequentes, metaphorice ethos definiunt vitae fontem, e quo singulae manant actiones.)146 In the Christian teaching we find the dogma of predestination in consequence of election and non-election by grace (Rom. ix, 11-24), obviously springing from the view that man does not change, but his life and conduct, in other words his empirical character, are only the unfolding of the intelligible character, the development of decided and unalterable tendencies already recognizable in the child. Therefore his conduct is, so to speak, fixed and settled even at his birth, and remains essentially the same to the very end. We too agree with this, but of course the consequences which resulted from the union of this perfectly correct view with the dogmas previously found in Jewish theology, and which gave rise to the greatest of all difficulties, namely to the eternally insoluble Gordian knot on which most of the controversies of the Church turn; these I do not undertake to defend. For even the Apostle Paul himself scarcely succeeded in doing this by his parable of the potter, invented for this purpose, for ultimately the result was in fact none other than this:

“Let the human race

Fear the gods!

They hold the dominion

In eternal hands:

And they can use it

As it pleases them.”

Goethe, Iphigenia [IV, 5].

But such considerations are really foreign to our subject. However, some observations on the relation between the character and the knowledge in which all its motives reside will here be appropriate.

The motives determining the phenomenon or appearance of the character, or determining conduct, influence the character through the medium of knowledge. Knowledge, however, is changeable, and often vacillates between error and truth; yet, as a rule, in the course of life it is rectified more and more, naturally in very different degrees. Thus a man’s manner of acting can be noticeably changed without our being justified in inferring from this a change in his character. What the man really and generally wills, the tendency of his innermost nature, and the goal he pursues in accordance therewith—these we can never change by influencing him from without, by instructing him, otherwise we should be able to create him anew. Seneca says admirably: velle non discitur;147 in this he prefers truth to his Stoic philosophers, who taught: διδαϰτὴν εἶναι τὴν ἀρετήν (doceri posse virtutem).148 From without, the will can be affected only by motives; but these can never change the will itself, for they have power over it only on the presupposition that it is precisely such as it is. All that the motives can do, therefore, is to alter the direction of the will’s effort, in other words to make it possible for it to seek what it invariably seeks by a path different from the one it previously followed. Therefore instruction, improved knowledge, and thus influence from without, can indeed teach the will that it erred in the means it employed. Accordingly, outside influence can bring it about that the will pursues the goal to which it aspires once for all in accordance with its inner nature, by quite a different path, and even in an entirely different object, from what it did previously. But such an influence can never bring it about that the will wills something actually different from what it has willed hitherto. This remains unalterable, for the will is precisely this willing itself, which would otherwise have to be abolished. However, the former, the ability to modify knowledge, and through this to modify action, goes so far that the will seeks to attain its ever unalterable end, for example, Mohammed’s paradise, at one time in the world of reality, at another in the world of imagination, adapting the means thereto, and so applying prudence, force, and fraud in the one case, abstinence, justice, righteousness, alms, and pilgrimage to Mecca in the other. But the tendency and endeavour of the will have not themselves been changed on that account, still less the will itself. Therefore, although its action certainly manifests itself differently at different times, its willing has nevertheless remained exactly the same. Velle non discitur.

For motives to be effective, it is necessary for them to be not only present but known; for according to a very good saying of the scholastics, which we have already mentioned, causa finalis movet non secundum suum esse reale, sed secundum esse cognitum.149 For example, in order that the relation which exists in a given man between egoism and sympathy may appear, it is not enough that he possesses some wealth and sees the misery of others; he must also know what can be done with wealth both for himself and for others. Not only must another’s suffering present itself to him, but he must also know what suffering is, and indeed what pleasure is. Perhaps on a first occasion he did not know all this so well as on a second; and if now on a similar occasion he acts differently, this is due simply to the circumstances being really different, namely as regards that part of them which depends on his knowledge of them, although they appear to be the same. Just as not to know actually existing circumstances deprives them of their effectiveness, so, on the other hand, entirely imaginary circumstances can act like real ones, not only in the case of a particular deception, but also in general and for some length of time. For example, if a man is firmly persuaded that every good deed is repaid to him a hundredfold in a future life, then such a conviction is valid and effective in precisely the same way as a safe bill of exchange at a very long date, and he can give from egoism just as, from another point of view, he would take from egoism. He himself has not changed: velle non discitur. In virtue of this great influence of knowledge on conduct, with an unalterable will, it comes about that the character develops and its different features appear only gradually. It therefore appears different at each period of life, and an impetuous, wild youth can be followed by a staid, sober, manly age. In particular, what is bad in the character will come out more and more powerfully with time; but sometimes passions to which a man gave way in his youth are later voluntarily restrained, merely because the opposite motives have only then come into knowledge. Hence we are all innocent to begin with, and this merely means that neither we nor others know the evil of our own nature. This appears only in the motives, and only in the course of time do the motives appear in knowledge. Ultimately we become acquainted with ourselves as quite different from what a priori we considered ourselves to be; and then we are often alarmed at ourselves.

Repentance never results from the fact that the will has changed —this is impossible—but from a change of knowledge. I must still continue to will the essential and real element of what I have always willed; for I am myself this will, that lies outside time and change. Therefore I can never repent of what I have willed, though I can repent of what I have done, when, guided by false concepts, I did something different from what was in accordance with my will. Repentance is the insight into this with more accurate knowledge. It extends not merely to worldly wisdom, the choice of means, and judging the appropriateness of the end to my will proper, but also to what is properly ethical. Thus, for example, it is possible for me to have acted more egoistically than is in accordance with my character, carried away by exaggerated notions of the need in which I myself stood, or even by the cunning, falseness, and wickedness of others, or again by the fact that I was in too much of a hurry; in other words, I acted without deliberation, determined not by motives distinctly known in the abstract, but by motives of mere perception, the impression of the present moment, and the emotion it excited. This emotion was so strong that I really did not have the use of my faculty of reason. But here also the return of reflection is only corrected knowledge, and from this repentance can result, which always proclaims itself by making amends for what has happened, so far as that is possible. But it is to be noted that, in order to deceive themselves, men prearrange apparent instances of precipitancy which are really secretly considered actions. For by such fine tricks we deceive and flatter no one but ourselves. The reverse case to what we have mentioned can also occur. I can be misled by too great confidence in others, or by not knowing the relative value of the good things of life, or by some abstract dogma in which I have now lost faith. Thus I act less egoistically than is in accordance with my character, and in this way prepare for myself repentance of another kind. Thus repentance is always corrected knowledge of the relation of the deed to the real intention. In so far as the will reveals its Ideas in space alone, that is to say, through mere form, the matter already controlled and ruled by other Ideas, in this case natural forces, resists the will, and seldom allows the form that was striving for visibility to appear in perfect purity and distinctness, i.e., in perfect beauty. This will, revealing itself in time alone, i.e., through actions, finds an analogous hindrance in the knowledge that rarely gives it the data quite correctly; and in this way the deed does not turn out wholly and entirely in keeping with the will, and therefore leads to repentance. Thus repentance always results from corrected knowledge, not from change in the will, which is impossible. Pangs of conscience over past deeds are anything but repentance; they are pain at the knowledge of oneself in one’s own nature, in other words, as will. They rest precisely on the certainty that we always have the same will. If the will were changed, and thus the pangs of conscience were mere repentance, these would be abolished; for then the past could no longer cause any distress, as it would exhibit the manifestations of a will that was no longer that of the repentant person. We shall discuss in detail the significance of pangs of conscience later on.

The influence exerted by knowledge as the medium of motives, not indeed on the will itself, but on its manifestation in actions, is also the basis of the chief difference between the actions of men and those of animals, since the methods of cognition of the two are different. The animal has only knowledge of perception, but man through the faculty of reason has also abstract representations, concepts. Now, although animal and man are determined by motives with equal necessity, man nevertheless has the advantage over the animal of a complete elective decision (Wahlentscheidung). This has often been regarded as a freedom of the will in individual actions, although it is nothing but the possibility of a conflict, thoroughly fought out, between several motives, the strongest of which then determines the will with necessity. For this purpose the motives must have assumed the form of abstract thoughts, since only by means of these is real deliberation, in other words, a weighing of opposed grounds for conduct, possible. With the animal a choice can take place only between motives of perception actually present; hence this choice is restricted to the narrow sphere of its present apprehension of perception. Therefore the necessity of the determination of the will by motives, like that of the effect by the cause, can be exhibited in perception and directly only in the case of the animals, since here the spectator has the motives just as directly before his eyes as he has their effect. In the case of man, however, the motives are almost always abstract representations; these are not shared by the spectator, and the necessity of their effect is concealed behind their conflict even from the person himself who acts. For only in abstracto can several representations lie beside one another in consciousness as judgements and chains of conclusions, and then, free from all determination of time, work against one another, until the strongest overpowers the rest, and determines the will. This is the complete elective decision or faculty of deliberation which man has as an advantage over the animal, and on account of which freedom of will has been attributed to him, in the belief that his willing was a mere result of the operations of his intellect, without a definite tendency to serve as its basis. The truth is, however, that motivation works only on the basis and assumption of his definite tendency, that is in his case individual, in other words, a character. A more detailed discussion of this power of deliberation and of the difference between human and animal free choice brought about by it, is to be found in Die Beiden Grundprobleme der Ethik (first edition, pp. 35 seqq., second edition, pp. 33 seqq.), to which therefore I refer. Moreover, this faculty for deliberation which man possesses is also one of the things that make his existence so very much more harrowing than the animal’s. For generally our greatest sufferings do not lie in the present as representations of perception or as immediate feeling, but in our faculty of reason as abstract concepts, tormenting thoughts, from which the animal is completely free, living as it does in the present, and thus in enviable ease and unconcern.

It seems to have been the dependence, described by us, of the human power of deliberation on the faculty of thinking in the abstract, and hence also of judging and inferring, which led both Descartes and Spinoza to identify the decisions of the will with the faculty of affirmation and denial (power of judgement). From this Descartes deduced that the will, according to him indifferently free, was to blame even for all theoretical error. On the other hand, Spinoza deduced that the will was necessarily determined by the motives, just as the judgement is by grounds or reasons.150 However, this latter deduction is quite right, though it appears as a true conclusion from false premisses.

The distinction which we have demonstrated between the ways in which the animal and man are each moved by motives has a very far-reaching influence on the nature of both, and contributes most to the complete and obvious difference in the existence of the two. Thus while the animal is always motivated only by a representa-tion of perception, man endeavours entirely to exclude this kind of motivation, and to let himself be determined only by abstract representations. In this way he uses his prerogative of reason to the greatest possible advantage, and, independent of the present moment, neither chooses nor avoids the passing pleasure or pain, but ponders over the consequences of both. In most cases, apart from quite insignificant actions, we are determined by abstract, considered motives, not by present impressions. Therefore, any particular privation for the moment is fairly light for us, but any renunciation is terribly hard. The former concerns only the fleeting present, but the latter concerns the future, and therefore includes in itself innumerable privations of which it is the equivalent. The cause of our pain as of our pleasure, therefore, lies for the most part not in the real present, but merely in abstract thoughts. It is these that are often unbearable to us, and inflict torments in comparison with which all the sufferings of the animal kingdom are very small; for even our own physical pain is often not felt at all when they are in question. Indeed, in the case of intense mental suffering, we cause ourselves physical suffering in order in this way to divert our attention from the former to the latter. Therefore in the greatest mental suffering men tear out their hair, beat their breasts, lacerate their faces, roll on the ground, for all these are really only powerful means of distraction from an unbearable thought. Just because mental pain, being much greater, makes one insensible to physical pain, suicide becomes very easy for the person in despair or consumed by morbid depression, even when previously, in comfortable circumstances, he recoiled from the thought of it. In the same way, care and passion, and thus the play of thought, wear out the body oftener and more than physical hardships do. In accordance with this, Epictetus rightly says: Tαράσσει τoὺς ἀνθρώπoυς oὐ τὰ πράγματα, ἀλλὰ τὰ περὶ τῶν πραγμάτων δόγματα (Perturbant homines non res ipsae, sed de rebus decreta) (Enchiridion, V)151 and Seneca: Plura sunt, quae nos terrent, quam quae premunt, et saepius opinione quam re laboramus (Ep. 5).152 Eulenspiegel also admirably satirized human nature, since when going uphill he laughed, but going downhill he wept. Indeed, children who have hurt themselves often cry not at the pain, but only at the thought of the pain, which is aroused when anyone condoles with them. Such great differences in conduct and suffering result from the diversity between the animal and human ways of knowing. Further, the appearance of the distinct and decided individual character that mainly distinguishes man from the animal, having scarcely more than the character of the species, is likewise conditioned by the choice between several motives, which is possible only by means of abstract concepts. For only after a precedent choice are the resolutions, which came about differently in different individuals, an indication of their individual character which is a different one in each case. On the other hand, the action of the animal depends only on the presence or absence of the impression, assuming that this is in general a motive for its species. Finally, therefore, in the case of man only the resolve, and not the mere wish, is a valid indication of his character for himself and for others. But for himself as for others the resolve becomes a certainty only through the deed. The wish is merely the necessary consequence of the present impression, whether of the external stimulus or of the inner passing mood, and is therefore as directly necessary and without deliberation as is the action of animals. Therefore, just like that action, it expresses merely the character of the species, not that of the individual, in other words, it indicates merely what man in general, not what the individual who feels the wish, would be capable of doing. The deed alone, because as human action it always requires a certain deliberation, and because as a rule man has command of his faculty of reason, and hence is thoughtful, in other words, decides according to considered abstract motives, is the expression of the intelligible maxims of his conduct, the result of his innermost willing. It is related as a letter is to the word that expresses his empirical character, this character itself being only the temporal expression of his intelligible character. Therefore in a healthy mind only deeds, not desires and thoughts, weigh heavily on the conscience; for only our deeds hold up before us the mirror of our will. The deed above mentioned, which is committed entirely without any thought and actually in blind emotion, is to a certain extent something between the mere wish and the resolve. Therefore through true repentance, which also shows itself in a deed, it can be obliterated as a falsely drawn line from the picture of our will, which our course of life is. Moreover, as a unique comparison, we may insert here the remark that the relation between wish and deed has an entirely accidental but accurate analogy to that between electrical accumulation and electrical discharge.

As a result of all this discussion on the freedom of the will and what relates to it, we find that, although the will in itself and apart from the phenomenon can be called free and even omnipotent, in its individual phenomena, illuminated by knowledge, and thus in persons and animals, it is determined by motives to which the character in each case regularly and necessarily always reacts in the same way. We see that, in virtue of the addition of abstract or rational knowledge, man has the advantage over the animal of an elective decision, which, however, simply makes him the scene of a conflict of motives, without withdrawing him from their control. Therefore this elective decision is certainly the condition of the possibility of the individual character’s complete expression, but it is by no means to be regarded as freedom of the individual willing, in other words, as independence of the law of causality, whose necessity extends to man as to every other phenomenon. Thus the difference produced between human and animal willing by the faculty of reason or knowledge by means of concepts extends as far as the point mentioned, and no farther. But, what is quite a different thing, there can arise a phenomenon of the human will which is impossible in the animal kingdom, namely when man abandons all knowledge of individual things as such, which is subordinate to the principle of sufficient reason, and, by means of knowledge of the Ideas, sees through the principium individuationis. An actual appearance of the real freedom of the will as thing-in-itself then becomes possible, by which the phenomenon comes into a certain contradiction with itself, as is expressed by the word self-renunciation, in fact the in-itself of its real nature ultimately abolishes itself. This sole and immediate manifestation proper of the freedom of the will in itself even in the phenomenon cannot as yet be clearly explained here, but will be the subject at the very end of our discussion.

After clearly seeing, by virtue of the present arguments, the unalterable nature of the empirical character which is the mere unfolding of the intelligible character that resides outside time, and also the necessity with which actions result from its contact with motives, we have first of all to clear away an inference that might very easily be drawn from this in favour of unwarrantable tendencies. Our character is to be regarded as the temporal unfolding of an extra-temporal, and so indivisible and unalterable, act of will, or of an intelligible character. Through this, all that is essential in our conduct of life, in other words its ethical content, is invariably determined, and must express itself accordingly in its phenomenon, the empirical character. On the other hand, only the inessential of this phenomenon, the external form of our course of life, depends on the forms in which the motives present themselves. Thus it might be inferred that for us to work at improving our character, or at resisting the power of evil tendencies, would be labour in vain; that it would therefore be more advisable to submit to the inevitable and unalterable, and to gratify at once every inclination, even if it is bad. But this is precisely the same case as that of the theory of inevitable fate, and of the inference drawn therefrom, which is called ἀργὸς λόγoς,153 and in more recent times Turkish or Mohammedan faith. Its correct refutation, as Chrysippus is supposed to have given it, is described by Cicero in his book De Fato, ch. 12, 13.

Although everything can be regarded as irrevocably predetermined by fate, it is so only by means of the chain of causes. Therefore in no case can it be determined that an effect should appear without its cause. Thus it is not simply the event that is predetermined, but the event as the result of preceding causes; and hence it is not the result alone, but also the means as the result of which it is destined to appear, that are settled by fate. Accordingly, if the means do not appear, the result also certainly does not appear; the two always exist according to the determination of fate, but it is always only afterwards that we come to know this.

Just as events always come about in accordance with fate, in other words, according to the endless concatenation of causes, so do our deeds always come about according to our intelligible character. But just as we do not know the former in advance, so also are we given no a priori insight into the latter; only a posteriori through experience do we come to know ourselves as we come to know others. If the intelligible character made it inevitable that we could form a good resolution only after a long conflict with a bad disposition, this conflict would have to come first and to be waited for. Reflection on the unalterable nature of the character, on the unity of the source from which all our deeds flow, should not mislead us into forestalling the decision of the character in favour of one side or the other. In the ensuing resolve we shall see what kind of men we are, and in our deeds we shall mirror ourselves. From this very fact is explained the satisfaction or agony of mind with which we look back on the course of our life. Neither of these results from past deeds still having an existence. These deeds are past; they have been, and now are no more, but their great importance to us comes from their significance, from the fact that such deeds are the impression or copy of the character, the mirror of the will; and, looking into this mirror, we recognize our innermost self, the kernel of our will. Because we experience this not before but only after, it is proper for us to fight and strive in time, simply in order that the picture we produce through our deeds may so turn out that the sight of it will cause us the greatest possible peace of mind, and not uneasiness or anxiety. The significance of such peace or agony of mind will, as we have said, be further investigated later. But the following discussion, standing by itself, belongs here.

Besides the intelligible and empirical characters, we have still to mention a third which is different from these two, namely the acquired character. We obtain this only in life, through contact with the world, and it is this we speak of when anyone is praised as a person who has character, or censured as one without character. It might of course be supposed that, since the empirical character, as the phenomenon of the intelligible, is unalterable, and, like every natural phenomenon, is in itself consistent, man also for this very reason would have to appear always like himself and consistent, and would therefore not need to acquire a character for himself artificially through experience and reflection. But the case is otherwise, and although a man is always the same, he does not always understand himself, but often fails to recognize himself until he has acquired some degree of real self-knowledge. As a mere natural tendency, the empirical character is in itself irrational; indeed its expressions are in addition disturbed by the faculty of reason, and in fact the more so, the more intellect and power of thought the man has. For these always keep before him what belongs to man in general as the character of the species, and what is possible for him both in willing and in doing. In this way, an insight into that which alone of all he wills and is able to do by dint of his individuality, is made difficult for him. He finds in himself the tendencies to all the various human aspirations and abilities, but the different degrees of these in his individuality do not become clear to him without experience. Now if he resorts to those pursuits that alone conform to his character, he feels, especially at particular moments and in particular moods, the impulse to the very opposite pursuits that are incompatible with them; and if he wishes to follow the former pursuits undisturbed, the latter must be entirely suppressed. For, as our physical path on earth is always a line and not a surface, we must in life, if we wish to grasp and possess one thing, renounce and leave aside innumerable others that lie to the right and to the left. If we cannot decide to do this, but, like children at a fair, snatch at everything that fascinates us in passing, this is the perverted attempt to change the line of our path into a surface. We then run a zigzag path, wander like a will-o’-the-wisp, and arrive at nothing. Or, to use another comparison, according to Hobbes’s doctrine of law, everyone originally has a right to everything, but an exclusive right to nothing; but he can obtain an exclusive right to individual things by renouncing his right to all the rest, while the others do the same thing with regard to what was chosen by him. It is precisely the same in life, where we can follow some definite pursuit, whether it be of pleasure, honour, wealth, science, art, or virtue, seriously and successfully only when we give up all claims foreign to it, and renounce everything else. Therefore mere willing and mere ability to do are not enough of themselves, but a man must also know what he wills, and know what he can do. Only thus will he display character, and only then can he achieve anything solid. Until he reaches this, he is still without character, in spite of the natural consistency of the empirical character. Although, on the whole, he must remain true to himself and run his course drawn by his daemon, he will not describe a straight line, but a wavering and uneven one. He will hesitate, deviate, turn back, and prepare for himself repentance and pain. All this because, in great things and in small, he sees before him as much as is possible and attainable for man, and yet does not know what part of all this is alone suitable and feasible for him, or even merely capable of being enjoyed by him. Therefore he will envy many on account of a position and circumstances which yet are suitable only to their character, not to his, in which he would feel unhappy, and which he might be unable to endure. For just as a fish is happy only in water, a bird only in the air, and a mole only under the earth, so every man is happy only in an atmosphere suitable to him. For example, not everyone can breathe the atmosphere of a court. From lack of moderate insight into all this, many a man will make all kinds of abortive attempts; he will do violence to his character in particulars, and yet on the whole will have to yield to it again. What he thus laboriously attains contrary to his nature will give him no pleasure; what he learns in this way will remain dead. Even from an ethical point of view, a deed too noble for his character, which has sprung not from pure, direct impulse, but from a concept, a dogma, will lose all merit even in his own eyes through a subsequent egoistical repentance. Velle non discitur. Only through experience do we become aware of the inflexibility of other people’s characters, and till then we childishly believe that we could succeed by representations of reason, by entreaties and prayers, by example and noble-mindedness, in making a man abandon his own way, change his mode of conduct, depart from his way of thinking, or even increase his abilities; it is the same, too, with ourselves. We must first learn from experience what we will and what we can do; till then we do not know this, are without character, and must often be driven back on to our own path by hard blows from outside. But if we have finally learnt it, we have then obtained what in the world is called character, the acquired character, which, accordingly, is nothing but the most complete possible knowledge of our own individuality. It is the abstract, and consequently distinct, knowledge of the unalterable qualities of our own empirical character, and of the measure and direction of our mental and bodily powers, and so of the whole strength and weakness of our own individuality. This puts us in a position to carry out, deliberately and methodically, the unalterable role of our own person, and to fill up the gaps caused in it by whims or weaknesses, under the guidance of fixed concepts. This role is in itself unchangeable once for all, but previously we allowed it to follow its natural course without any rule. We have now brought to clearly conscious maxims that are always present to us, the manner of acting necessarily determined by our individual nature. In accordance with these, we carry it out as deliberately as though it were one that had been learnt, without ever being led astray by the fleeting influence of the mood or impression of the present moment, without being checked by the bitterness or sweetness of a particular thing we meet with on the way, without wavering, without hesitation, without inconsistencies. Now we shall no longer, as novices, wait, attempt, and grope about, in order to see what we really desire and are able to do; we know this once for all, and with every choice we have only to apply general principles to particular cases, and at once reach a decision. We know our will in general, and do not allow ourselves to be misled by a mood, or by entreaty from outside, into arriving at a decision in the particular case which is contrary to the will as a whole. We also know the nature and measure of our powers and weaknesses, and shall thus spare ourselves much pain and suffering. For there is really no other pleasure than in the use and feeling of our own powers, and the greatest pain is when we are aware of a deficiency of our powers where they are needed. Now if we have found out where our strong and weak points lie, we shall attempt to develop, employ, and use in every way those talents that are naturally prominent in us. We shall always turn to where these talents are useful and of value, and shall avoid entirely and with self-restraint those pursuits for which we have little natural aptitude. We shall guard against attempting that in which we do not succeed. Only the man who has reached this will always be entirely himself with complete awareness, and will never fail himself at the critical moment, because he has always known what he could expect from himself. He will then often partake of the pleasure of feeling his strength, and will rarely experience the pain of being reminded of his weaknesses. The latter is humiliation, which perhaps causes the greatest of mental suffering. Therefore we are far better able to endure the clear sight of our ill-luck than that of our incapacity. Now if we are thus fully acquainted with our strength and weakness, we shall not attempt to display powers we do not possess; we shall not play with false coin, because such dissimulation in the end misses its mark. For as the whole man is only the phenomenon of his will, nothing can be more absurd than for him, starting from reflection, to want to be something different from what he is; for this is an immediate contradiction of the will itself. Imitating the qualities and idiosyncrasies of others is much more outrageous than wearing others’ clothes, for it is the judgement we ourselves pronounce on our own worthlessness. Knowledge of our own mind and of our capabilities of every kind, and of their unalterable limits, is in this respect the surest way to the attainment of the greatest possible contentment with ourselves. For it holds good of inner as of outer circumstances that there is no more effective consolation for us than the complete certainty of unalterable necessity. No evil that has befallen us torments us so much as the thought of the circumstances by which it could have been warded off. Therefore nothing is more effective for our consolation than a consideration of what has happened from the point of view of necessity, from which all accidents appear as tools of a governing fate; so that we recognize the evil that has come about as inevitably produced by the conflict of inner and outer circumstances, that is, fatalism. We really wail or rage only so long as we hope either to affect others in this way, or to stimulate ourselves to unheard-of efforts. But children and adults know quite well how to yield and to be satisfied, as soon as they see clearly that things are absolutely no different;

(Animo in pectoribus nostro domito necessitate.)154

We are like entrapped elephants, which rage and struggle fearfully for many days, until they see that it is fruitless, and then suddenly offer their necks calmly to the yoke, tamed for ever. We are like King David who, so long as his son was still alive, incessantly implored Jehovah with prayers, and behaved as if in despair; but as soon as his son was dead, he thought no more about him. Hence we see that innumerable permanent evils, such as lameness, poverty, humble position, ugliness, unpleasant dwelling-place, are endured with complete indifference, and no longer felt at all by innumerable persons, just like wounds that have turned to scars. This is merely because they know that inner or outer necessity leaves them nothing here that could be altered. On the other hand, more fortunate people do not see how such things can be endured. Now as with outer necessity so with inner, nothing reconciles so firmly as a distinct knowledge of it. If we have clearly recognized once for all our good qualities and strong points as well as our defects and weaknesses; if we have fixed our aim accordingly, and rest content about the unattainable, we thus escape in the surest way, as far as our individuality allows, that bitterest of all sufferings, dissatisfaction with ourselves, which is the inevitable consequence of ignorance of our own individuality, of false conceit, and of the audacity and presumption that arise therefrom. Ovid’s verses admit of admirable application to the bitter chapter of self-knowledge that is here recommended:

Optimus ille animi vindex laedentia pectus

Vincula qui rupit, dedoluitque semel.155

So much as regards the acquired character, that is of importance not so much for ethics proper as for life in the world. But a discussion of it was related to that of the intelligible and empirical characters, and we had to enter into a somewhat detailed consideration of it in order to see clearly how the will in all its phenomena is subject to necessity, while in itself it can be called free and even omnipotent.