§ 63.

We have learnt to recognize temporal justice, which has its seat in the State, as requiting or punishing, and have seen that this becomes justice with regard only to the future. For without such regard, all punishing and requital of an outrage would remain without justification, would indeed be a mere addition of a second evil to that which had happened, without sense or significance. But it is quite different with eternal justice, which has been previously mentioned, and which rules not the State but the world; this is not dependent on human institutions, not subject to chance and deception, not uncertain, wavering, and erring, but infallible, firm, and certain. The concept of retaliation implies time, therefore eternal justice cannot be a retributive justice, and hence cannot, like that, admit respite and reprieve, and require time in order to succeed, balancing the evil deed against the evil consequence only by means of time. Here the punishment must be so linked with the offence that the two are one.

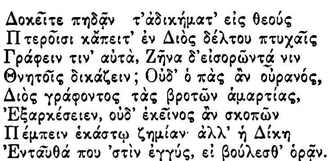

Euripides, Apud Stobaeus, Eclog., I, c. 4.

(Volare pennis scelera ad aetherias domus

Putatis, illic in Jovis tabularia

Scripto referri; tum Jovem lectis super

Sententiam proferre? sed mortalium

Facinora coeli, quantaquanta est, regia

Nequit tenere: nec legendis Juppiter

Et puniendis par est. Est tamen ultio,

Et, si intuemur, illa nos habitat prope.)176

Now that such an eternal justice is actually to be found in the inner nature of the world will soon become perfectly clear to the reader who has grasped in its entirety the thought that we have so far developed.

The phenomenon, the objectivity of the one will-to-live, is the world in all the plurality of its parts and forms. Existence itself, and the kind of existence, in the totality as well as in every part, is only from the will. The will is free; it is almighty. The will appears in everything, precisely as it determines itself in itself and outside time. The world is only the mirror of this willing; and all finiteness, all suffering, all miseries that it contains, belong to the expression of what the will wills, are as they are because the will so wills. Accordingly, with the strictest right, every being supports existence in general, and the existence of its species and of its characteristic individuality, entirely as it is and in surroundings as they are, in a world such as it is, swayed by chance and error, fleeting, transient, always suffering; and in all that happens or indeed can happen to the individual, justice is always done to it. For the will belongs to it; and as the will is, so is the world. Only this world itself—no other—can bear the responsibility for its existence and its nature; for how could anyone else have assumed this responsibility? If we want to know what human beings, morally considered, are worth as a whole and in general, let us consider their fate as a whole and in general. This fate is want, wretchedness, misery, lamentation, and death. Eternal justice prevails; if they were not as a whole contemptible, their fate as a whole would not be so melancholy. In this sense we can say that the world itself is the tribunal of the world. If we could lay all the misery of the world in one pan of the scales, and all its guilt in the other, the pointer would certainly show them to be in equilibrium.

But of course the world does not exhibit itself to knowledge which has sprung from the will to serve it, and which comes to the individual as such in the same way as it finally discloses itself to the inquirer, namely as the objectivity of the one and only will-to-live, which he himself is. On the contrary, the eyes of the uncultured individual are clouded, as the Indians say, by the veil of Maya. To him is revealed not the thing-in-itself, but only the phenomenon in time and space, in the principium individuationis, and in the remaining forms of the principle of sufficient reason. In this form of his limited knowledge he sees not the inner nature of things, which is one, but its phenomena as separated, detached, innumerable, very different, and indeed opposed. For pleasure appears to him as one thing, and pain as quite another; one man as tormentor and murderer, another as martyr and victim; wickedness as one thing, evil as another. He sees one person living in pleasure, abundance, and delights, and at the same time another dying in agony of want and cold at the former’s very door. He then asks where retribution is to be found. He himself in the vehement pressure of will, which is his origin and inner nature, grasps the pleasures and enjoyments of life, embraces them firmly, and does not know that, by this very act of his will, he seizes and hugs all the pains and miseries of life, at the sight of which he shudders. He sees the evil, he sees the wickedness in the world; but, far from recognizing that the two are but different aspects of the phenomenon of the one will-to-live, he regards them as very different, indeed as quite opposed. He often tries to escape by wickedness, in other words, by causing another’s suffering, from the evil, from the suffering of his own individuality, involved as he is in the principium individuationis, deluded by the veil of Maya. Just as the boatman sits in his small boat, trusting his frail craft in a stormy sea that is boundless in every direction, rising and falling with the howling, mountainous waves, so in the midst of a world full of suffering and misery the individual man calmly sits, supported by and trusting the principium individuationis, or the way in which the individual knows things as phenomenon. The boundless world, everywhere full of suffering in the infinite past, in the infinite future, is strange to him, is indeed a fiction. His vanishing person, his extensionless present, his momentary gratification, these alone have reality for him; and he does everything to maintain them, so long as his eyes are not opened by a better knowledge. Till then, there lives only in the innermost depths of his consciousness the wholly obscure presentiment that all this is indeed not really so strange to him, but has a connexion with him from which the principium individuationis cannot protect him. From this presentiment arises that ineradicable dread, common to all human beings (and possibly even to the more intelligent animals), which suddenly seizes them, when by any chance they become puzzled over the principium individuationis, in that the principle of sufficient reason in one or other of its forms seems to undergo an exception. For example, when it appears that some change has occurred without a cause, or a deceased person exists again; or when in any other way the past or the future is present, or the distant is near. The fearful terror at anything of this kind is based on the fact that they suddenly become puzzled over the forms of knowledge of the phenomenon which alone hold their own individuality separate from the rest of the world. This separation, however, lies only in the phenomenon and not in the thing-in-itself; and precisely on this rests eternal justice. In fact, all temporal happiness stands, and all prudence proceeds, on undermined ground. They protect the person from accidents, and supply it with pleasures, but the person is mere phenomenon, and its difference from other individuals, and exemption from the sufferings they bear, rest merely on the form of the phenomenon, on the principium individuationis. According to the true nature of things, everyone has all the sufferings of the world as his own; indeed, he has to look upon all merely possible sufferings as actual for him, so long as he is the firm and constant will-to-live, in other words, affirms life with all his strength. For the knowledge that sees through the principium individuationis, a happy life in time, given by chance or won from it by shrewdness, amid the sufferings of innumerable others, is only a beggar’s dream, in which he is a king, but from which he must awake, in order to realize that only a fleeting illusion had separated him from the suffering of his life.

Eternal justice is withdrawn from the view that is involved in knowledge following the principle of sufficient reason, in the principium individuationis; such a view altogether misses it, unless it vindicates it in some way by fictions. It sees the wicked man, after misdeeds and cruelties of every kind, live a life of pleasure, and quit the world undisturbed. It sees the oppressed person drag out to the end a life full of suffering without the appearance of an avenger or vindicator. But eternal justice will be grasped and comprehended only by the man who rises above that knowledge which proceeds on the guiding line of the principle of sufficient reason and is bound to individual things, who recognizes the Ideas, who sees through the principium individuationis, and who is aware that the forms of the phenomenon do not apply to the thing-in-itself. Moreover, it is this man alone who, by dint of the same knowledge, can understand the true nature of virtue, as will soon be disclosed to us in connexion with the present discussion, although for the practice of virtue this knowledge in the abstract is by no means required. Therefore, it becomes clear to the man who has reached the knowledge referred to, that, since the will is the in-itself of every phenomenon, the misery inflicted on others and that experienced by himself, the bad and the evil, always concern the one and the same inner being, although the phenomena in which the one and the other exhibit themselves stand out as quite different individuals, and are separated even by wide intervals of time and space. He sees that the difference between the inflicter of suffering and he who must endure it is only phenomenon, and does not concern the thing-in-itself which is the will that lives in both. Deceived by the knowledge bound to its service, the will here fails to recognize itself; seeking enhanced well-being in one of its phenomena, it produces great suffering in another. Thus in the fierceness and intensity of its desire it buries its teeth in its own flesh, not knowing that it always injures only itself, revealing in this form through the medium of individuation the conflict with itself which it bears in its inner nature. Tormentor and tormented are one. The former is mistaken in thinking he does not share the torment, the latter in thinking he does not share the guilt. If the eyes of both were opened, the inflicter of the suffering would recognize that he lives in everything that suffers pain in the whole wide world, and, if endowed with the faculty of reason, ponders in vain over why it was called into existence for such great suffering, whose cause and guilt it does not perceive. On the other hand, the tormented person would see that all the wickedness that is or ever was perpetrated in the world proceeds from that will which constitutes also his own inner being, and appears also in him. He would see that, through this phenomenon and its affirmation, he has taken upon himself all the sufferings resulting from such a will, and rightly endures them so long as he is this will. In Life a Dream the prophetic poet Calderón speaks from this knowledge:

Pues el delito mayor

Del hombre es haber nacido.

(For man’s greatest offence

Is that he has been born.)

How could it fail to be an offence, as death comes after it in accordance with an eternal law? In that verse Calderón has merely expressed the Christian dogma of original sin.

The vivid knowledge of eternal justice, of the balance inseparably uniting the malum culpae with the malum poenae, demands the complete elevation above individuality and the principle of its possibility. It will therefore always remain inaccessible to the majority of men, as also will the pure and distinct knowledge of the real nature of all virtue which is akin to it, and which we are about to discuss. Hence the wise ancestors of the Indian people have directly expressed it in the Vedas, permitted only to the three twice-born castes, or in the esoteric teaching, namely in so far as concept and language comprehend it, and in so far as their method of presentation, always pictorial and even rhapsodical, allows it. But in the religion of the people, or in exoteric teaching, they have communicated it only mythically. We find the direct presentation in the Vedas, the fruit of the highest human knowledge and wisdom, the kernel of which has finally come to us in the Upanishads as the greatest gift to the nineteenth century. It is expressed in various ways, but especially by the fact that all beings of the world, living and lifeless, are led past in succession in the presence of the novice, and that over each of them is pronounced the word which has become a formula, and as such has been called the Mahavakya: Tatoumes, or more correctly, tat tvam asi, which means “This art thou.”177 For the people, however, that great truth, in so far as it was possible for them to comprehend it with their limited mental capacity, was translated into the way of knowledge following the principle of sufficient reason. From its nature, this way of knowledge is indeed quite incapable of assimilating that truth purely and in itself; indeed it is even in direct contradiction with it; yet in the form of a myth, it received a substitute for it which was sufficient as a guide to conduct. For the myth makes intelligible the ethical significance of conduct through figurative description in the method of knowledge according to the principle of sufficient reason, which is eternally foreign to this significance. This is the object of religious teachings, since these are all the mythical garments of the truth which is inaccessible to the crude human intellect. In this sense, that myth might be called in Kant’s language a postulate of practical reason (Vernunft), but, considered as such, it has the great advantage of containing absolutely no elements but those which lie before our eyes in the realm of reality, and thus of being able to support all its concepts with perceptions. What is here meant is the myth of the transmigration of souls. This teaches that all sufferings inflicted in life by man on other beings must be expiated in a following life in this world by precisely the same sufferings. It goes to the length of teaching that a person who kills only an animal, will be born as just such an animal at some point in endless time, and will suffer the same death. It teaches that wicked conduct entails a future life in suffering and despised creatures in this world; that a person is accordingly born again in lower castes, or as a woman, or as an animal, as a pariah or Chandala, as a leper, a crocodile, and so on. All the torments threatened by the myth are supported by it with perceptions from the world of reality, through suffering creatures that do not know how they have merited the punishment of their misery; and it does not need to call in the assistance of any other hell. On the other hand, it promises as reward rebirth in better and nobler forms, as Brahmans, sages, or saints. The highest reward awaiting the noblest deeds and most complete resignation, which comes also to the woman who in seven successive lives has voluntarily died on the funeral pile of her husband, and no less to the person whose pure mouth has never uttered a single lie—such a reward can be expressed by the myth only negatively in the language of this world, namely by the promise, so often occurring, of not being reborn any more: non adsumes iterum existentiam apparentem;178 or as the Buddhists, admitting neither Vedas nor castes, express it: “You shall attain to Nirvana, in other words, to a state or condition in which there are not four things, namely birth, old age, disease, and death.”

Never has a myth been, and never will one be, more closely associated with a philosophical truth accessible to so few, than this very ancient teaching of the noblest and oldest of peoples. Degenerate as this race may now be in many respects, this truth still prevails with it as the universal creed of the people, and it has a decided influence on life today, as it had four thousand years ago. Therefore Pythagoras and Plato grasped with admiration that non plus ultra of mythical expression, took it over from India or Egypt, revered it, applied it, and themselves believed it, to what extent we know not. We, on the contrary, now send to the Brahmans English clergymen and evangelical linen-weavers, in order out of sympathy to put them right, and to point out to them that they are created out of nothing, and that they ought to be grateful and pleased about it. But it is just the same as if we fired a bullet at a cliff. In India our religions will never at any time take root; the ancient wisdom of the human race will not be supplanted by the events in Galilee. On the contrary, Indian wisdom flows back to Europe, and will produce a fundamental change in our knowledge and thought.