James Philpott had a sea story or two to tell. Shipwrecked three times, his final skirmish on the North Atlantic was his tale of disgust and how charity showed him discourtesy.

On February 20, 1922, while on a journey from Cadiz laden with salt for St. John’s, the J. N. Rafuse, owned by the J. T. Moulton firm of Burgeo, was abandoned in mid-ocean and the crew taken off by the Norwegian steamer Terrier. The latter vessel was en route to Liverpool, England.

In the process of transferring the shipwrecked sailors to the steamer, the lifeboat capsized and three from the Rafuse were drowned: Captain George Harvey, aged twenty-eight and single, of Fortune; Mate Ambrose King, twenty-five, Marystown; and Cook Ephriam Billard, thirty-three, of Burgeo. As well, the first mate of the Terrier, who was in charge of the lifeboat, drowned.

Three others of the J. N. Rafuse’s crew—Bosun L. Janes and John Clothier, both of Burgeo, and James Philpott of Jamestown, Bonavista Bay—survived. Captain Harvey had taken command of the Rafuse a few months before and was on his first overseas voyage on her. He had previously commanded the General Byng out of Grand Bank.

Survivor James Philpott, born in Jamestown in 1897, found a berth on the J. N. Rafuse because of a family connection. His youngest sister, Leona Philpott, was married to Tom Harvey of Fortune.

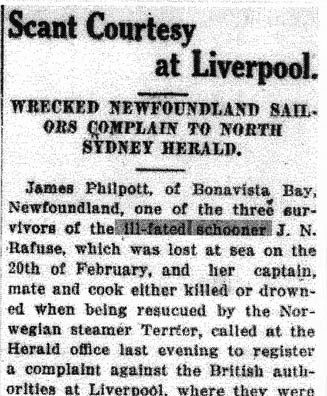

Philpott’s story of survival on the J. N. Rafuse was initially documented in the Nova Scotian paper North Sydney Herald on March 17, 1922—nearly a month after he was shipwrecked. He and his two shipmates had been taken off their sinking schooner wearing only the clothes on their backs. Extra clothes, duffle bags, and personal possessions had gone down with the J. N. Rafuse.

When the rescuer, Terrier, reached Liverpool, the three survivors were landed at Liverpool. Philpott stated that such was the harsh treatment by British authorities he could hardly believe it. The bare necessities were all they received: “We were by force of circumstance given food, lodging, and some clothing by the shipping officer at Liverpool.”

But that’s where amenities ended. Although it was March month with freezing winds and inclement weather, Philpott, Janes, and Clothier were refused mitts or gloves to protect them from the cold. He stated:

We were given only the thinnest of cotton socks. It would be supposed that (we) would be given a few shillings to purchase little extras, such as tobacco, blades for a shave, and so on. But such “dainties” were looked on by the British as outrageous.

That Philpott was disgusted with his treatment as a shipwrecked sailor was an understatement, yet it was he who voiced his opinion of the haughty attitude of the shipping officer in Liverpool. When he and his two mates reached North Sydney, it was entirely the opposite reception.

They had obtained a passage westward in Liverpool and arrived in North Sydney in mid-March 1922. There the three survivors were met by Arthur William Shano, the director of Newfoundland post services in North Sydney. Shano also had the duty of receiving and accommodating shipwrecked Newfoundland sailors. James Philpott said:

It was different when we struck North Sydney. Nothing seemed to be too good for us. Mr. A. W. Shano is a prince among Newfoundlanders, and he made our stay in Nova Scotia a most pleasant one—just like home, as it were.

The same applies to the good people of North Sydney, who we will not forget in the future.

In time, James Philpott and his two fellow sailors were given a passage to Newfoundland and eventually reached their homes. However, before he finished his account with the North Sydney Herald, Philpott summarized his two previous shipwreck misadventures.

The first time he had a clash with the sea was aboard the schooner Yukon. This ninety-seven-ton schooner was owned by Philip Templeman of Bonavista. It had been built in La Have, Nova Scotia, in 1900, and six years later was purchased by Templeman. He put the Yukon in the herring trade.

In the March 27, 1922, edition of a local paper, a survivor of the loss of the J. N. Rafuse speaks of his ill treatment at a major seaport.

With James Philpott as one of the crew (the names of the others and the captain is not clear), it loaded herring at the Bay of Islands on May 8, 1919. With that cargo landed safely, it again loaded herring at St. George’s and sailed for Halifax on September 3 that same year. A few days later, the Yukon struck the shoals of Egg Island, twenty miles south of Halifax. There were no injuries. Philpott arrived back in St. John’s via the SS Rosalind on September 19, 1919.

In October, he joined A. E. Hickman and Company’s schooner Bluenose (as distinct from Nova Scotia’s famed racer, the Bluenose). It was destined to carry a load of salt dry fish to Europe but never reached port. Storm-battered and leaky, the Bluenose was abandoned in mid-ocean. Unlike the loss of the J. N. Rafuse, James Philpott and crew were all rescued without incident.

James Philpott passed away in Pasadena in 1988.