Like the Bay of Portugal – Rosalind’s Love Life

Rosalind’s first genius is for love. She’s the agent and initiator of love in her play, setting the whole whirligig in motion. ‘Let me see,’ she asks Celia mischievously, ‘what think you of falling in love?’ She discovers for herself what extreme love feels like, though the extremities to which it drives people like Orlando are absurd in her sane, witty opinion.

Rosalind’s second genius is for language. The most passionate and rational female lover in western drama talks in soaring prose cadenzas to express every facet of love. Passion can make people irrational but Rosalind’s love is clear sighted – and expressed in prose. Anticipating both the Enlightenment and the Romantics, she is both rational and ardent. This virgin who has fun’1 as Camille Paglia describes her, is a linguistic Houdini who fizzes like a firecracker as she detonates all the clichés about love. She’s both comic and serious; a risk taker prepared to shatter romantic myths at the same time as confessing the oceanic depth of her love. Shakespeare was thirty-five and at the height of his virtuoso powers when he brought immortal Rosalind joyously to life. Spanning both sexes, Rosalind sprints into Arden like an envoy from Shakespeare himself. The year of As You Like It, 1599, was indeed an annus mirabilis for Shakespeare, when he wrote not only Rosalind’s comedy but also the English history play, Henry V; a Roman play, Julius Caesar; and his great tragedy, Hamlet.2

‘Would you believe in a love at first sight?’ asked the Beatles. ‘Yes, I’m certain that it happens all the time.’ But why does Rosalind fall in love at first sight with Orlando, the youngest son of Sir Rowland de Boys? And why is Shakespeare so interested in this human phenomenon? It doesn’t affect the heroine of Rosalynde, his immediate source in Thomas Lodge’s earlier novella of 1590. Nevertheless, Shakespeare chooses to make love at first sight the impetus for Rosalind’s progress from green girl to the intensity of sexual desire. What makes Rosalind unusual is that she can observe passion and heartache through irony, ruses, jokes and prose.

‘Who ever loved that loved not at first sight?’ asked Christopher Marlowe in his poem, Hero and Leander, a question so universal that Shakespeare quoted it verbatim in Rosalind’s play. It spills from Phebe, the susceptible shepherdess, when she falls in love at first sight with Rosalind dressed as the sweet youth’ Ganymede. Phebe is quoting Marlowe, murdered in 1593 in a Deptford tavern.

| Phebe | Dead shepherd, now I find thy saw of might: ‘Who ever loved, that loved not at first sight?’3 |

As Rosalind discovers, love at first sight strikes like a miracle though it feels like being mugged. That’s why Cupid comes armed with bow and arrows. Actor Pippa Nixon who played the role in the RSC production of 2013 asked why this sort of love hits Rosalind. ‘How can you fall in love at first sight? Actually, in a world that at the beginning feels quite hopeless, and there’s no hope – it’s a miracle.’4 Trapped in a world of no hope, the court of her wicked uncle, it’s obvious that Rosalind is primed for love at first sight. Perhaps the miracle is that it hasn’t happened sooner.

Shakespeare also examines love at first sight in A Midsummer Nights Dream, Twelfth Night, and most famously in Romeo and Juliet. In Verona, Juliet and Romeo fall in love the moment they meet. Like Rosalind and Orlando, they both come from dysfunctional families. Unlike Orlando, Romeo has been in love before, infatuated with Rosaline a previous girlfriend, before he ever glimpses Juliet. But rather than with Rosaline, he’s been in love with love, which he vents in clichés and embroidered similes.

| Romeo | Is love a tender thing? It is too rough, Too rude, too boisterous, and it pricks like thorn.5 |

However, when he sees Juliet for the first time, he realises he’s never really been in love before, nor appreciated true beauty.

| Romeo | O, she doth teach the torches to burbnright. It seems she hangs upon the cheek of night Like a rich jewel in an Ethiop’s ear – Beauty too rich for use, for earth too dear. ... Did my heart love till now? Forswear it, sight. For I ne’er saw true beauty till this night.6 |

As they join first hands and then lips, Juliet tells Romeo you kiss by the book’. Though she’s less than fourteen years old, she instantly recognises her ‘true love’s passion’. She’s shrewder than Romeo, as Rosalind is wiser about love than Orlando. Like Rosalind, Juliet is deeply suspicious of facile language. She ticks off Romeo for swearing by the moon, the hackneyed and ‘inconstant moon’. When he tries to invoke some other cliché to swear by, she repeats impatiently, ‘Do not swear at all...Well, do not swear.’ Bored by empty oaths, she forges ahead and proposes to Romeo – as Rosalind will, twice, to Orlando. Like Rosalind in the later play, Juliet moves the action.

| Juliet | Three words, dear Romeo, and good night indeed. If that thy bent of love be honourable, Thy purpose marriage, send me word tomorrow By one that I’ll procure to come to thee, Where and what time thou wilt perform the rite, And all my fortunes at thy foot I’ll lay, And follow thee my lord throughout the world.7 |

Actor Juliet Rylance thinks Rosalind and Juliet are the only two Shakespearean women to take the initiative in love from the outset. ‘Juliet runs with the story. And the same willpower that Rosalind has, they both share that incredible willpower: I will achieve my goal, or I will be a man, or I will test his love...I think Juliet’s large in the same way as Rosalind.’ I asked Rylance whether she thought people can and do fall in love at first sight? I think I fell instantly in love with Christian [Camargo]. I actually fell in love with him while I was playing Romeo and Juliet at the Middle Temple Hall.’8

For Rosalind and Orlando, Juliet and Romeo, love at first sight strikes like a spark on dry tinder in their violent worlds. Gang warfare between the Capulets and Montagues runs wild in Verona. In this setting blooms the unlooked-for flower of love. The worlds surrounding Rosalind and Orlando are also vicious and corrupt. Political order is disrupted and so is family order. In an atmosphere bristling with physical danger, love at first sight is a jewel of great price. Dangerous situations can catapult you into love. By contrast, Shakespeare shows other loves at first sight that can be self-deceptive, such as Phebe’s sudden passion for doppelgänger Ganymede/Rosalind, or Olivia’s for double agent Cesario/Viola in Twelfth Night.

Four centuries before Rylance experienced love at first sight, Shakespeare showed the force with which love can rage, either across the genders or between people of the same sex. In Rosalind, he shows love ignited in a hostile environment. When Orlando wrestles with Duke Frederick’s brawny champion and wins, against all the odds, it’s the catalyst for love. ‘Sir,’ breathes Rosalind with instant self-knowledge, ‘you have wrestled well, and overthrown/More than your enemies.’ Orlando, in his turn, falls just as spontaneously in love with ‘heavenly Rosalind’.

The only person Rosalind can confide in is cousin Celia who reproves her smartly, ‘Come, come, wrestle with thy affections.’ Celia is quick to sense the causal link between Orlando’s victory in the wrestling – and in Rosalind’s heart. Why is Rosalind so silent and withdrawn, asks Celia, ‘is all this for your father?’ Rosalind flashes back, ‘No, some of it is for my child’s father. O, how full of briers is this working-day world!’ The immediate brier is Uncle Frederick’s loathing of Orlando de Boys’ family and lineage. The Duke’s emotions stem from the same branch of deadly feuding that divides the Montagues and Capulets. Swiftly cutting through the briers of family politics, Rosalind mentally fast-forwards to her future children. The biological imperative may be primitive and unconscious but it’s one of the substrata beneath young heterosexual love. Rosalind openly demonstrates this drive. Her desire has compelling fertility purposes, as she frankly celebrates.

Her love for Orlando is based first on physical attraction and romantic longing. But soon she combines body and soul, head and heart. Inspired by finding a fit father for her future children, she unleashes the masculine as well as the feminine sides of her nature to go and get exactly what she wants. In a similar way, masculine Orlando is entirely comfortable with his feminine side. They match with perfect complementarity. Finding each other, they illustrate Plato’s theory of love, as a search for the lost other half of oneself.

But before Rosalind can pursue any outcome to love at first sight with Orlando, unforeseen political events intervene. Uncle Frederick, usurper of her father’s dukedom, orders her deportation from court. At a stroke, she finds herself cast out of society, and even pitched out of her gender, in flight to the Forest of Arden disguised as Ganymede. Transvestism is her ingenious scheme to escape the death penalty Duke Frederick has placed on her head. Yet within her new boy’s exterior, she carries the thumping heart of first love.

Once in Arden, together with cousin Celia disguised as Ganymede’s peasant sister Aliena, and the court fool, Touchstone, they overhear shepherd Silvius proclaiming his hopeless, troubadourish love for Phebe, a shepherdess: ‘O Phebe, Phebe, Phebe!’ His pain pierces Rosalind’s soul, reminding her of her own one-sided love for Orlando. Since she impetuously gave him her necklace at the wrestling match, she hasn’t heard a single word from Orlando. Silvius’s love for Phebe could be Rosalind’s own heart speaking. Alas, poor shepherd! Searching of thy wound, I have by hard adventure found mine own.’ Not to be outdone, Touchstone interjects, And I mine.’ He soars into an improvisation on his own previous love, or lust, for dairymaid, Jane Smile.

| Touchstone | I remember when I was in love I broke my sword upon a stone and bid him take that for coming a-night to Jane Smile; and I remember the kissing of her batlet, [butter paddle] and the cow’s dugs that her pretty chopped hands had milked; and I remember the wooing of a peascod instead of her, from whom I took two cods, and, giving her them again, said with weeping tears: ‘Wear these for my sake.’ We that are true lovers run into strange capers. But as all is mortal in nature, so is all nature in love mortal in folly.9 |

Touchstone and Jane Smile, as well as all the other couples in the play, constantly refract one another like musical themes, recapitulated and rephrased. As we revolve these differing love pairings, we wonder which has the best chance of enduring. Rosalind instantly recognises Touchstone’s experience of the craziness of love, ‘Thou speak’st wiser than thou art ware of.’ Seeing her own love through the filters of Silvius’s poetic, Petrarchan love for Phebe, and Touchstone’s raunchy carnal love, soon to be transferred to goatherd Audrey, only intensifies Rosalind’s yearning. Literary critic, Anna Jameson, understood this exactly. In her book, Shakespeare’s Heroines, first published in 1832, she wrote, ‘Passion, when we contemplate it through the medium of imagination, is like a ray of light transmitted through a prism: we can calmly, and with undazzled eye, study its complicate [sic] nature and analyse its variety of tints; but passion brought home to us in its reality, through our own feelings and experience, is like the same ray transmitted through a lens, – blinding, burning, consuming where it falls.’10

Shakespeare had the brilliance to convey what his heroines felt when falling in love for the first time. And he endowed them with far greater freedom of action than Anna Jameson’s contemporary male writers: Dickens, Thackeray and Trollope. Novelist and critic, Rebecca West, noticed this in the mid-twentieth century. ‘It would have been astounding to find a Juliet in their pages. None of the three would have respected her passion as Shakespeare respected it, for the double reason that it was beautiful in itself and that it had a right to exist, like her own body...like all sound processes of nature.’ Rosalind, like Juliet, is at ease with her body and its desires, as she is with the intensity of her emotions. But, Rebecca West conceded, one among the male Victorian novelists, Anthony Trollope, ‘was a feminist.’11

Like Shakespeare nearly three centuries ahead of him, Trollope showed special empathy with women and the female experience of falling in love. Trollope’s final novel in his Palliser series, The Duke’s Children of 1880, is sprinkled with references to As You Like It.12 Trollope understood the heart of another duke’s daughter, Lady Mary Palliser, whose father, the Duke of Omnium, was the ‘brier’ opposed to her love match with Mr Francis Tregear. Like Orlando, Tregear was a gentleman of no fortune, though ‘as beautiful as Apollo.’ Trollope described Mary’s boundless love as well as her absolute tenacity in pursuing it. However, she had none of Ganymede’s freedom of action, nor would it have occurred to her to jump gender like Rosalind. But Mary was very sure that her first and deepest love for Mr Tregear ‘had become a bond almost as holy as matrimony itself.’ Mary’s first love has the same aura of sanctity as Rosalind’s. Kissing Orlando is as ‘full of sanctity as the touch of holy bread,’ she says. In Mary’s case, as in Rosalind’s, ‘No other man had ever whispered a word of love to her, of no other man had an idea entered her mind that it could be pleasant to join her lot in life with his. With her it had been all new and all sacred. Love with her had that religion which nothing but freshness can give it.’13 Like Shakespeare, Trollope understood that first love thrills by its very newness.

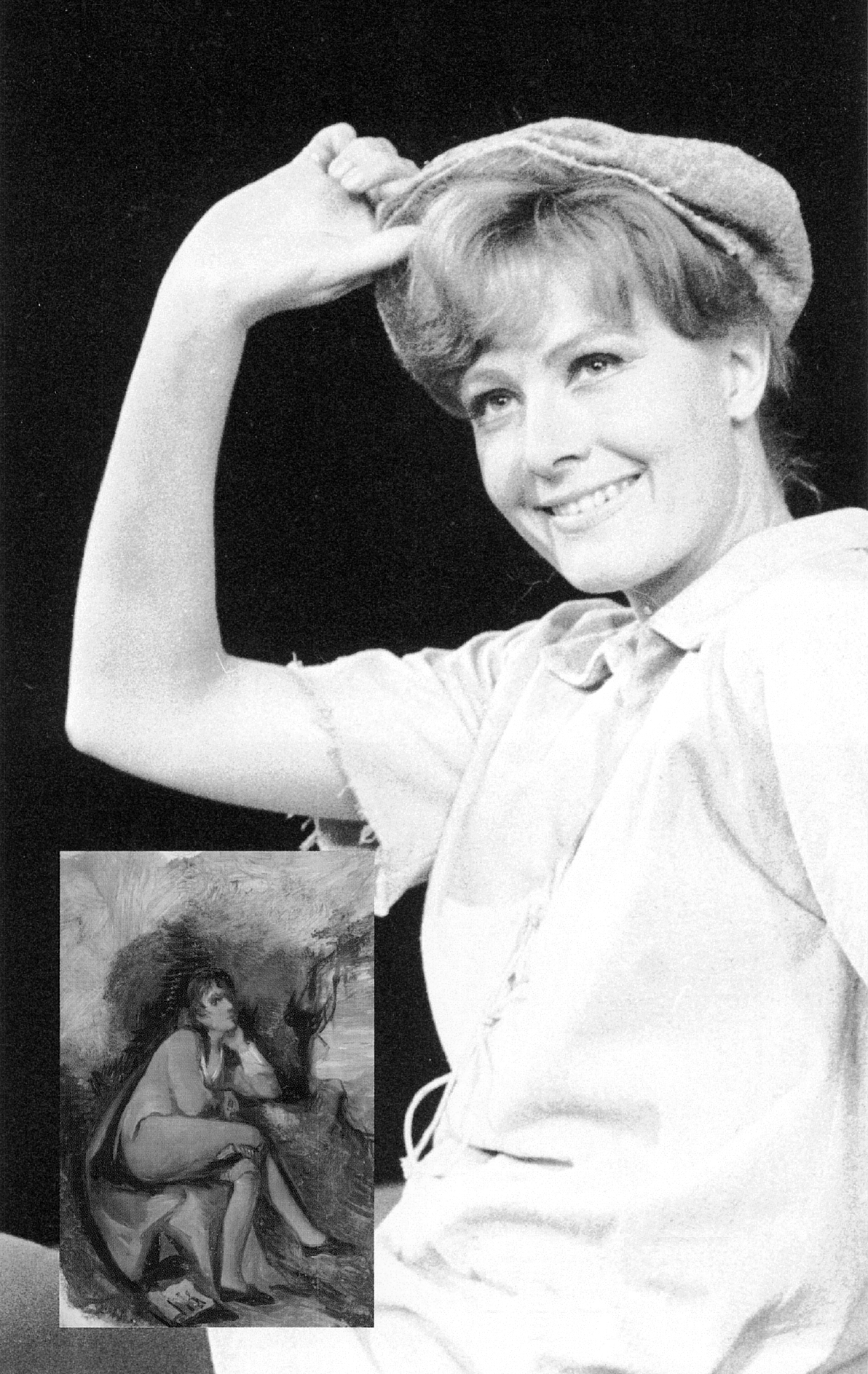

1. Vanessa Redgrave a Rosalind for the RSC, 1961–63

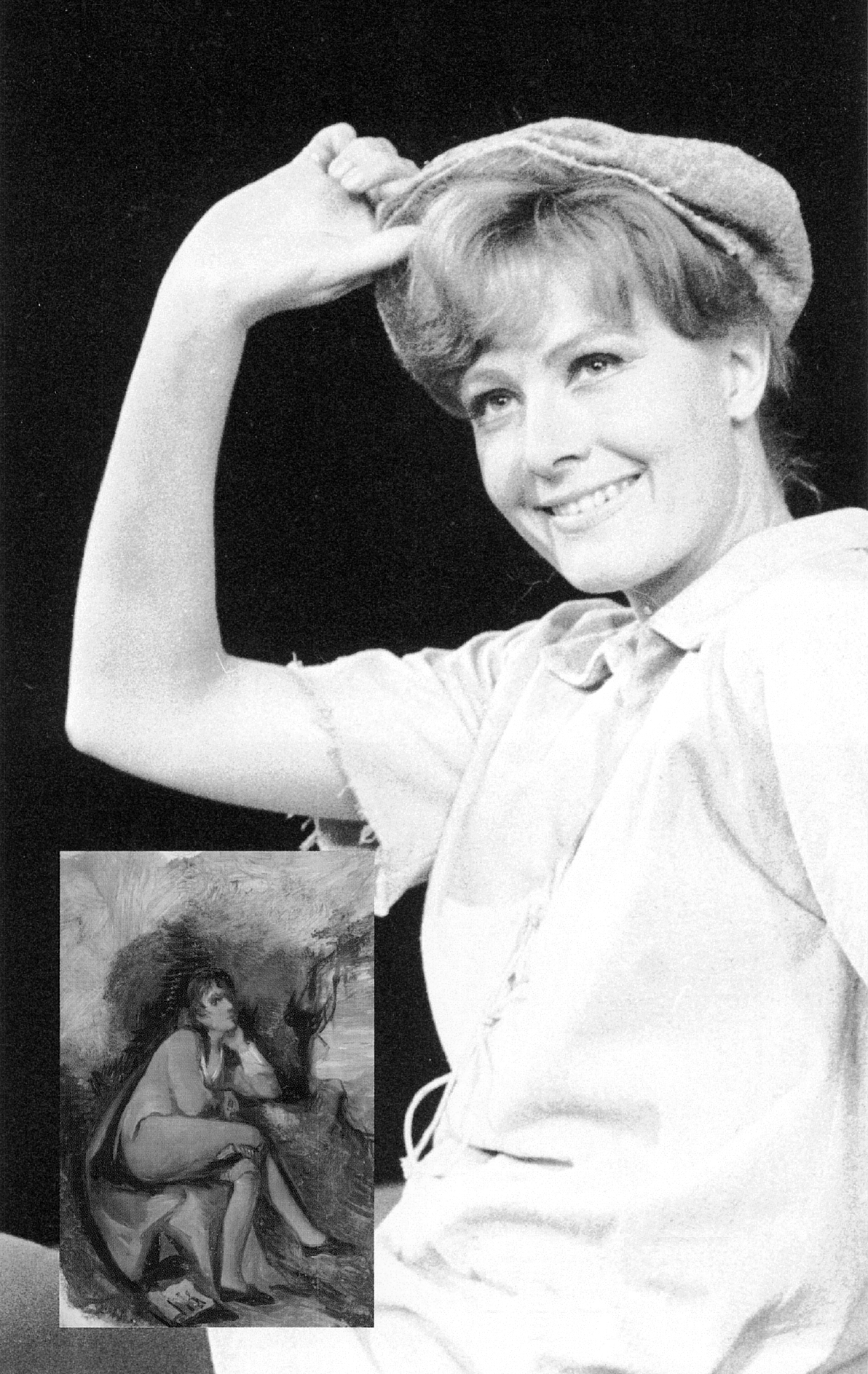

2. (left) Mrs siddons as Rosalind by Joseph Wright of Derby. c. 1778

3. Ganymede with Zeus disguised as an eagle by Berrel Thorvaldsen, 1817

4. Valentine rescuing Silvia from Proteus by William Holman Hunt, 1850–51, from Shakespeare’s play The Two Gentlemen of Verona

5. Rebecca Hall as Rosalind at Theatre Royal Bath and in the USA, 2003;

6. Janet Suzman as Rosalind for the RSC, 1968;

7. Sally Scott as Rosalind (lelf) with Kaisa Hammarlund as Celia (right) at the Southwark Playhouse, 2014

8. Juliet Rylance as Rosalind with Christian Camargo as Orlando at The Old Vic, 2010;

9. Adrian Lester (right) as Rosalind for Cheek by Jowl, 1991;

10. The Mock Marriage of Orlando and Rosalind (with Celia looking on) by Walter Deverell, 1853

11. Pippa Nixon as Rosalind for the RSC, 2013;

12. Edith Evans (top) as Rosalind at The Old Vic, 1936/7;

13. Juliet Stevenson (left) as Rosalind with Fiona Shaw (right) as Celia for the RSC, 1985

14. Katharine Hepburn as Rosalind with William Prince as Orlando on Broadway, 1950;

15. Laurence Olivier as Orlando in the 1936 film of As You Like It;

16. Ronald Pickup as Rosalind at The Old Vic, 1967

17. Helen Faucit, one of the great Victorian Rosalinds

18. Dorothy Jordan as Rosalind by Sir William Beechey, 1787

19. Elisabeth Bergner as Rosalind in the 1936 film of As You Like It

20. Cush Jumbo as Rosalind at the Royal Exchange Theatre Manchester for which she won the Ian Charleson Award 2012

21. (Below) Rosalind in As You Like It by Arthur Hughes, 1871–3

Rosalind’s love has that same elation. I talked recently to Jean Hewison, a chic and elegant octogenarian, who played Rosalind in the open air when she was twenty-one. ‘Honestly, I think it’s young love. It’s got to be fresh, like a sudden blossoming, it’s spring, and it’s all happening.’14 Youthful it may be, but Rosalind’s love is universal, too, and people of all ages relate to its exuberance.

In her state of heightened consciousness, Rosalind finds Orlando’s love poems pinned on Arden’s greenwood trees. After wringing the poet’s identity out of Celia, Rosalind finds herself initially trapped in the persona of Ganymede. But she makes disguise her best friend. It’s her passport to freedom, a carte blanche to tell the truth about love to the man she hopes may become her life’s partner. ‘It’s the old conundrum of truth-telling’, observes Janet Suzman. ‘You tell the truth when you have a disguise upon you...Truth-telling can only properly be done when you are well disguised. That is the only reason to be an artist: to try to tell the truth.’15 Rosalind seizes upon playacting as a route to the truth, to examine the sincerity of Orlando’s love and verify her own. For as Walter Pater observed, ‘Play is often that about which people are most serious.’16

‘The premise that this person [Ganymede] does not exist, cannot exist gives you more licence to talk about love’, says Adrian Lester who played Rosalind in 1991. ‘Young love really hurts, you’re a slave of your feelings, there’s an inner violence to them. She’s more Rosalind when she’s Ganymede – and yet she has to keep control of her sexual passions. It’s a very complex situation for Rosalind.’17 Perhaps it was a complex situation for Rosalind’s original audience, too. Played by a boy, first in formal female court dress, then in double-crossing costume as Ganymede, did they even see her as a woman at all? Or was the convention so accepted as to be unremarkable? In the transvestite figure of Rosalind, Shakespeare could embody the ferocity of love, which affects both sexes.

By healing the split between male and female in the actor playing triply cross-dressed Rosalind, Shakespeare captures what love feels like for both sexes, in every time and place. Shortly after the fall of the Berlin Wall, I got talking with a group of Latvian banking delegates during their coffee break at a hotel near Stratford-upon-Avon. I asked, tentatively, if they were going to see any Shakespeare on their first trip to England? The group leader leapt in. ‘Of course we’re going to see a play! Don’t you realise Shakespeare is not for the English? He is for Latvia, he is for all Latvians, he is for the world!’ Rosalind’s love is comprehensive in this Latvian spirit, cross-cultural, international and, yes, dual gendered. S/he belongs to our collective experience. Harold Bloom observes, ‘A great role, like Rosalind’s, is a kind of miracle: a universal perspective seems to open out upon us.’18 ‘Miracle’ seems to attach itself to Rosalind, the same word actor Pippa Nixon used to describe Rosalind’s love.

As Rosalind grows from untouched innocence to the full frankness of sexual desire for Orlando, she becomes aware of her uncharted capacity for love. ‘My affection hath an unknown bottom like the Bay of Portugal.’19 The seas between Oporto and the Cape of Cintra off the coast of Portugal sink to a vast depth of up to 1400 fathoms. It’s not just an outlandish simile. It expresses exactly what Rosalind feels – and it would have been topical. Living in the exhilarating Age of Discovery, Shakespeare fired Rosalind’s mind with all the latest marine knowledge. On tenterhooks to learn the author of the love poems strewn across Arden, she berates Celia with another metaphor from the new navigation. ‘One inch of delay more is a South Sea of discovery’.20 An extra moment’s prevarication seems as endless to Rosalind as an Elizabethan explorer’s journey to the South Pacific. Her imagery circumnavigates the known world, as it then was.

How do you understand the power of love if you’ve never been in love before, especially if you’re a motherless girl? ‘The absence of mothers always puts women in a state of crisis from the start. They are unprotected, they are always alone in the world, even if the world is a drawing-room’, says actor Fiona Shaw who has played both Rosalind and Celia.21 Pre-Orlando, Rosalind’s only experience of intimacy and love has flowed to her from cousin Celia.

The two cousins have never been in love with anyone else. They share a unique bond as they’ve only known the love of one another. Teenage girls may or may not love each other in a sexual way, and Celias today may choose openly the love of women. Each production makes its own interpretation of the Rosalind-Celia friendship. In Sam Mendes’ version at the Old Vic in 2010, Michelle Beck’s Celia played the relationship with Rosalind like best friends who have grown up together, ‘until a man shows up and changes everything,’ says Juliet Rylance, and they go through that, the next stage of development.’22 Watching Beck, I sensed that Celia felt left behind by Rosalind. When Rosalind fell in love with Orlando, Celia just stood there and suddenly became Aliena, the persona she will take on in Arden. She was literally alienated. Her love for Rosalind had been superseded. But Rosalind grows and takes flight from Celia’s selfless love. It’s her springboard into love for Orlando. And she doesn’t look back. That’s the cruelty of love.

Up to the point where the two cousins leave Duke Frederick’s court in disguise, it could have been Celia’s play. Once Rosalind makes the decision to flee to Arden dressed as a boy, she becomes the main protagonist and the focus of all eyes. She’s now a performer with the freedom first to approach Orlando, and later to propose to him, not just once, but twice. Proposing to a man at the end of the sixteenth century was seriously transgressive. Yet Juliet also proposes. Both Rosalind and Juliet mastermind their own courtships in a comedy and a tragedy. But Rosalind isn’t just an actor in her own drama. She’s director, producer, scriptwriter, and stage manager, too.

The language of theatre infuses As You Like It. Duke Senior exiled in the forest, finds comfort in the metaphor of life as theatre, or the playhouse as life.

| Duke Senior | Thou seest we are not all alone unhappy: This wide and universal theatre Presents more woeful pageants than the scene Wherein we play in.23 |

The Duke’s image and his half-line are immediately picked up by Jaques as he sashays into the most often quoted speech of the play, ‘All the world’s a stage...’ referring to the words possibly flown on the flag-pole at the new Globe Playhouse in 1599: Totus mundus agit histrionem – the whole world plays the actor.24 Theatre is life itself, life is theatre, and Rosalind the star in her own drama. Her only counterpart, later, will be Prospero.

Like Prospero, Rosalind is the impresario and organising spirit of her play. To action her love, Rosalind takes control of events in Arden, even when her transvestite situation threatens to become fatally embarrassing. ‘Alas the day!’ she groans when Celia reveals that Orlando is also in the forest, ‘What shall I do with my doublet and hose?’ It is here in Act III at the very epicentre of Shakespeare’s 5-act play that Rosalind and Orlando encounter each other for only the second time. This centrality is significant. For their love is the centre of the play, as poet John Donne’s bed is the centre of his room and of his relationship with his lover.25 Rosalind in role as Ganymede now has the space to test the truthfulness of Orlando’s heart whose poems seem to proclaim the depth of his affection.

Once Orlando admits he is indeed the author of poems in praise of someone called Rosalind, Ganymede can ask him direct the consuming question, ‘But are you so much in love as your rhymes speak?’ She could never have asked this as Rosalind, and it’s ‘the absolute crux of the scene,’ thinks actor Rebecca Hall. Then Orlando ‘answers her better than she can possibly imagine: “Neither rhyme nor reason can express how much.” And it floors her. And she realises that she’s utterly in love too. The whole thing is terrifying. This next speech is so beautiful and I love it. It’s almost my favourite,’ says Hall.

| Rosalind | Love is merely a madness, and, I tell you deserves as well a dark house and a whip as madmen do; and the reason why they are not so punished and cured is that the lunacy is so ordinary that the whippers are in love too.26 |

In Hall’s view, Rosalind ‘suddenly has this incredible lucidity about love. It’s sort of rueful...For every funny thing she says, there’s an undercurrent of reality as well, of the slightly frightening nature of it all. And she’s not being flippant, she really does think love is completely crazy...It’s all crazy. Love is mad. And yet we run our lives by it.’27

Love feels like madness for both Rosalind and Orlando, but Rosalind applies her mind as well as her emotions to it. Her love is as profound as Juliet’s but she tempers it with her own sardonic voice when she lectures on love to her lover. W.H. Auden clearly heard the rational, civilized voice of Rosalind. ‘It’s very sophisticated, and only adults can understand what [the play’s] about. You have to be acquainted with what it means to be a civilized person...Of all of Shakespeare’s plays, As You Like It is the greatest paean to civilization and to the nature of a civilized man and woman. It is dominated by Rosalind, a triumph of civilization, who like the play itself, fully embodies man’s capacity, in Pascal’s words, “to deny, to believe, and to doubt well” – nier, croire, et douter bien,’28

Rosalind’s sophisticated reasoning about love is electrifying. She wants to explore the implications of precipitate, headstrong love. If love is a madness as she warns him, it is also an illness from which Orlando has no wish to be cured. But cure’ is the word that inspires Rosalind with the germ of her brilliant scheme. Safe in her actor’s invented male self, she proposes impersonating the ‘real’ Rosalind. ‘I would cure you,’ she lures Orlando, ‘if you would but call me Rosalind and come every day to my cote to woo me.’ Let’s pretend we’re lovers by proxy. Let’s play a flirting game. Behind the mask of Ganymede, Rosalind is free to speak the truth about love and her heart. Hitherto, a woman in a man’s world, constricted by dress and expectation, disguise now awards her the freedom of a spy in action. In her game-changing way, Rosalind plots to get exactly what she wants: Orlando, the object of her loving at first sight.

Rosalind was the breakthrough role in Vanessa Redgrave’s career, says her daughter, Joely Richardson. It made Redgrave a star for the RSC in Stratford and London in 1961, and more people saw it when the production was broadcast in 1963. During Shakespeare’s Women, a BBC TV programme made by Richardson in 2012, Redgrave told her daughter how close the 1961 production had come to disaster. At the end of six weeks in rehearsal, director Michael Elliott told her: ‘Vanessa, if you don’t give yourself to this play, you are going to ruin this production!’29 Playing Rosalind is like diving, thinks Redgrave, you have to give yourself to the water, you have to abandon yourself to the part. Abandonment worked. ‘The naturalness, the unforced understanding of her playing, the passionate, breathless conviction of it, the depth of feeling and the breadth of reality – this is not acting at all, but living, being, loving,’ wrote critic Bernard Levin of Redgrave’s performance.30 Rosalind as Ganymede is acting but, paradoxically, her finest acting is not an act. Redgrave found the scene in which Ganymede offers to cure Orlando of love by pretending to be Rosalind, one of the most heartfelt scenes in Shakespeare.

Rosalind’s seesaw adventure takes her from romance to realism and back again. Having issued instructions for a play courtship, she lets Orlando go, only to find her confidence dissolving, like him, into the forest. She demands of herself and of Celia, her confidante and sounding board, ‘But why did he swear he would come this morning, and comes not?’ It’s the question with which all lovers torment themselves. But Celia is cold comfort. She voices Rosalind’s worst fears, and all lovers’ foreboding of rejection.

| Celia | Nay certainly, there is no truth in him. |

| Rosalind | Do you think so? |

| Celia | Yes. I think he is not a pick-purse nor a horse-stealer – but for his verity in love I do think him as concave as a covered goblet or a worm-eaten nut. |

| Rosalind | Not true in love? |

| Celia | Yes, when he is in, but I think he is not in. |

| Rosalind | You have heard him swear downright he was. |

| Celia | ‘Was’ is not ‘is.’ Besides, the oath of a lover is no stronger than the word of a tapster: they are both the confirmer of false reckonings.31 |

Falling in love is fraught with dangers. Falling out of love is one of them. Love’s risks are as great as its rewards. Rosalind sees rejection presented before her very eyes when she watches the next episode in the rolling Silvius-Phebe love story. Rosalind is the pattern of all lovers in her fear of rejection, of the future, and of the confusing nature of time. ‘The creeping hours of time,’ as Orlando says, seem to pass so slowly, fail to bring the longed for results, or wing by too swiftiy. It’s all too short a step from love to time, and hence to mortality; sexual climax the little death that foreshadows the great oblivion.

‘There’s no clock in the forest’ but the characters are acutely aware of time in all its phases. Seen from afar, the life of Duke Senior’s exiled court glows in an aura of Edenic time, in spite of winter weather and physical hardship. As Charles the wrestler reports:

| Charles | They say he is already in the Forest of Arden and a many merry men with him, and there they live like the old Robin Hood of England. They say many young gentlemen flock to him every day and fleet the time carelessly as they did in the golden world.32 |

But like a death-knell, time tolls against Rosalind when her uncle banishes her.

| Duke Frederick | If you outstay the time, upon mine honour And in the greatness of my word, you die.33 |

Celia transmutes her father’s threat of outstaying time by her greathearted offer to flee the court with Rosalind.

| Celia | Let’s away, |

| And get our jewels and our wealth together, Devise the fittest time and safest way To hide us from pursuit that will be made After my flight.34 |

Arriving in Arden safe in their disguises, a new kind of forest time stretches ahead for the cousins. ‘I like this place/And willingly could waste my time in it,’ Celia announces.35 It’s the spirit of asolare, the word Robert Browning defined as to disport in the open air, amuse oneself at random,’ when almost three hundred years after Arden he found himself happily wasting time in the small Italian town of Asolo.36

Everyone in Arden seems obsessed with time. Touchstone, the court fool, impresses Jaques with an aria on clocks counting the hours of life, as he pulls a sun-dial out of his pocket, and,

| Jaques | Says very wisely, ‘It is ten o’clock. Thus we may see’, quoth he, ‘how the world wags. ’Tis but an hour ago since it was nine, And after one hour more ’twill be eleven. And so from hour to hour we ripe and ripe, And then from hour to hour we rot and rot, And thereby hangs a tale.’37 |

Time’s action is not only the preoccupation of lovers but it is also the relendess engine that drives Jaques’ famous speech on the stages of human life.

| Jaques | All the world’s a stage, |

| And all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances, And one man in his time plays many parts, His acts being seven ages.38 |

Within the play’s framework of philosophising about time passing, Ganymede/Rosalind accosts Orlando for the first time in Arden. A time check is as corny as spies asking for a light in old black and white movies.

| Rosalind | I pray you, what is’t o’clock? |

| Orlando | You should ask me what time o’day. There’s no clock in the forest. |

| Rosalind | Then there is no true lover in the forest, else sighing every minute and groaning every hour would detect the lazy foot of time as well as a clock. |

| Orlando | And why not the swift foot of time? Had not that been as proper? |

| Rosalind | By no means, sir. Time travels in divers paces with divers persons. I’ll tell you who Time ambles withal, who Time trots withal, who Time gallops withal and who he stands still withal. |

| Orlando | I prithee, who doth he trot withal? |

| Rosalind | Marry, he trots hard with a young maid between the contract of her marriage and the day it is solemnized. If the interim be but a se’nnight, Time’s pace is so hard that it seems the length of seven year. |

| Orlando | Who ambles Time withal? |

| Rosalind | With a priest that lacks Latin, and a rich man that hath not the gout; for the one sleeps easily because he cannot study, and the other lives merrily because he feels no pain; the one lacking the burden of lean and wasteful learning, the other knowing no burden of heavy tedious penury. These Time ambles withal. |

| Orlando | Who doth he gallop withal? |

| Rosalind | With a thief to the gallows; for though he go as softly as foot can fall, he thinks himself too soon there. |

| Orlando | Who stays it still withal? |

| Rosalind | With lawyers in the vacation; for they sleep between term and term and then they perceive not how time moves.39 |

Ganymede darts insights at Orlando about the psychological contortions of time. Straight man Orlando feeds Ganymede questions to provoke ever more inventive answers. The conversation escalates into an aria of comic and dazzling images. Rosalind makes a lot out of these similes about Time. Or she could be struggling to complete the comparisons she’s set herself, as an in-joke against the script-writer’s fanciful word-play.

Reviewers who saw Edith Evans play Rosalind in 1936/7 thought her the only actress ‘who could think of the things Shakespeare makes her say. She is equal to her wit instead of being nonplussed by it. She might, in short, have written the part.’ Rosalind convinces us, of course, that she’s making up the words as she goes along. Although Edith Evans was not the obvious physical type to play lissome Rosalind, she created impudence and lightness, proving that conventional notions of feminine beauty are no obstacle to inhabiting the role. ‘Does she make you fall in love with her? That is not her business. It is her business to make you fall in love with Orlando, and at the Old Vic in 1936 Edith Evans triumphantly [made] you experience her emotions.’ ‘She can move like an arrow, she can roll over the ground in a delight of comedy, she can mock and glitter.’40

When Orlando avows he is indeed the Arden love poet with the ‘quotidian of love upon him,’ Rosalind seizes the opportunity to uncover the truth about him. If that’s your problem, ‘I profess curing it by counsel,’ says naughty Ganymede. Come round to mine every day and let’s pretend I’m your Rosalind. I’ll show you what women are really like and you’ll soon desist. It’s a therapy that’s worked before with a previous lovesick fellow, s/he lies. This way ‘will I take upon me to wash your liver as clean as a sound sheep’s heart, that there shall not be one spot of love in’t.’41 Though he has no wish to be cured of his love, Orlando is up for the game. So when Ganymede invites him, ‘Will you go?’ he answers, ‘With all my heart, good youth.’ But the ‘boy’ reminds him, ‘Nay you must call me Rosalind.’

In the merry war of love that now ensues, themes of play-acting and reality merge in Rosalind’s badinage.

| Orlando | ...and my Rosalind is virtuous. |

| Rosalind | And I am your Rosalind. |

| Celia | It pleases him to call you so, but he hath a Rosalind of a better leer than you. |

| Rosalind | Come, woo me, woo me – for now I am in a holiday humour and like enough to consent. What would you say to me now, an I were your very, very Rosalind? |

| Orlando | I would kiss before I spoke. |

| Rosalind | Nay, you were better speak first, and when you were gravelled for lack of matter you might take occasion to kiss. Very good orators when they are out, they will spit, and for lovers lacking (God warrant us) matter, the cleanliest shift is to kiss. |

| Orlando | How if the kiss be denied? |

| Rosalind | Then she puts you to entreaty and there begins new matter. |

| Orlando | Who could be out, being before his beloved mistress? |

| Rosalind | Marry, that should you, if I were your mistress, or I should think my honesty ranker than my wit. |

| Orlando | What, of my suit? |

| Rosalind | Not out of your apparel and yet out of your suit. Am not I your Rosalind? |

| Orlando | I take some joy to say you are because I would be talking of her. |

| Rosalind | Well, in her person, I say I will not have you.42 |

Rosalind tries to deny her heart at the same time as she challenges his. She distrusts his romantic hyperbole. Her tough blend of reason and ardour makes her an unusually brave human being. She would have approved the song, Let us all ring Fancy’s knell./ I’ll begin it. Ding, dong, bell.43 Yet, in spite of her suspicions about romantics, she is fervently in love with Orlando. So successful is Rosalind’s strategy to examine Orlando’s authenticity, so unsuccessful is Ganymede’s strategy to wash his liver clean of love, that at only their second forest tryst, he’s as eager as s/he is to participate in their faux wedding officiated by Celia. Rosalind’s passionate desire for Orlando is the centre about which the whole play moves.

| Rosalind | I do take thee, Orlando, for my husband. There’s a girl goes before the priest, and certainly a woman’s thought runs before her actions. |

| Orlando | So do all thoughts – they are winged. |

| Rosalind | Now tell me how long you would have her after you have possessed her? |

| Orlando | For ever and a day. |

| Rosalind | Say ‘a day’ without the ‘ever’. No, no, Orlando, men are April when they woo, December when they wed. Maids are May when they are maids, but the sky changes when they are wives.44 |

Rosalind contains apparent opposites. Though impassioned, she’s also bleakly realistic. She seems to know instinctively that marriage can curdle romance. Rosalind is this and she is that. She even changes sex mid-speech when she imagines herself ‘a Barbary cock-pigeon’. Juliet Stevenson notices how Rosalind subverts gender stereotypes [and] notions of love as they have been passed down through literature and through society. The very state of marriage is an unequal state historically. It was created for the patrilineal line. It was created to keep women under. It’s quite a patriarchal institution as it exists, though these words are modern words used in modern times. It would be inappropriate to suggest that Shakespeare was questioning patriarchy. But it doesn’t matter what words you use. The ideas are the same.’45

Even from the depths of her emotional vortex, Rosalind can be cerebral almost to the point of cynicism. Her verbal skirmishes with Orlando are whip sharp. She’s determined to raise all the negatives about women, love and marriage, and to deflate Orlando’s claims for endless adoration. Adrian Lester thinks ‘the play shows us the romantic idea of love and then the reality of it. Rosalind has had her heart broken by members of her own family. She is weak and powerless. Then along comes a man with whom she falls completely in love. But upon meeting him she realises that he is in love with the idea of her, not with who she really is.’46 In the 1940 movie, The Philadelphia Story, Katharine Hepburn’s character, Tracy Lord, thought like Rosalind, ‘I don’t want to be worshipped, I want to be loved...really loved.’ Ten years later Hepburn was obvious casting for Rosalind on Broadway.

With her innate wisdom, Rosalind understands that the first delirium of young love will not last, that December will follow May. The seasons constantly murmur an elegiac burden to lovers’ time. Immediately after her mock wedding with Orlando, Rosalind’s speeding mind recurs to time – which torments all lovers. Alas! dear love, I cannot lack thee two hours.’ Lovers’ time is here and now, ‘’Tis not hereafter,’ as Feste the Clown sings in Twelfth Night, the play most often coupled with As You Like It. The songs in Shakespeare’s comedies were part of popular theatre, like musicals today. Songs punctuate Rosalind’s play like mood music, light as bubbles even when they sound a melancholy note. In the Elizabethan world picture, music was an echo of the heavenly spheres. It could lead its listeners towards perfection. Even though love’s springtime marches inevitably towards winter and rough weather,’ the songs in Shakespeare’s comedies inspire lovers to transcend time’s tragedy.

Amiens, official vocalist to Duke Senior’s exiled court, voices this theme in the first of six songs in As You Like It.

| Under the greenwood tree | |

| Who loves to lie with me | |

| And turn [tune] his merry note | |

| Unto the sweet bird’s throat, | |

| Come hither, come hither, come hither! | |

| Here shall he see no enemy | |

| But winter and rough weather... |

| Who doth ambition shun | |

| And loves to live i’th’ sun, | |

| Seeking the food he eats | |

| And pleased with what he gets, | |

| Come hither, come hither, come hither! | |

| Here shall he see no enemy | |

| But winter and rough weather.47 |

And he reiterates the chill of winter weather in his second song:

| Freeze, freeze, thou bitter sky, | |

| That dost not bite so nigh | |

| As benefits forgot. | |

| Though thou the waters warp, | |

| Thy sting is not so sharp | |

| As friend remembered not. | |

| Hey-ho, sing hey-ho, unto the green holly.48 |

By the time Amiens sings this, Orlando has already proved that his old servant Adam is far from forgotten. Orlando carries him, fainting from hunger, to Duke Senior’s feast in the forest, and man’s ingratitude is reversed. In 2013 the RSC made the play’s songs freshly contemporary by commissioning singer Laura Marling to compose modern settings for its famous lyrics. The songs easily crossed the four centuries since they were written and found a new resonance with today’s audience. Music moves love on to universal and timeless planes.

In the build-up to the joyful conclusion of the play, two young pages sing Thomas Morley’s pop song of its day, ‘It was a lover and his lass.’ Springtime becomes ‘ringtime’, literally, because four weddings are about to be celebrated. Four couples will jubilantly ‘take the present time’ and seize the day.

| It was a lover and his lass, | |

| With a hey and a ho and a hey nonino, | |

| That o’er the green cornfield did pass, | |

| In spring-time, the only pretty ring-time, | |

| When birds do sing, hey ding a ding a ding, | |

| Sweet lovers love the spring. |

| Between the acres of the rye, | |

| With a hey and a ho and a hey nonino, | |

| These pretty country folks would lie, | |

| In spring-time, &c. |

| This carol they began that hour, | |

| With a hey and a ho and a hey nonino, | |

| How that a life was but a flower, | |

| In springtime, &c. |

| And therefore take the present time, | |

| With a hey and a ho and a hey nonino, | |

| For love is crowned with the prime, | |

| In spring-time, &c.49 |

Composer, organist, and probably counter-tenor, Morley set this poem to music in his First Book of Ayres in 1600.50 It’s the only contemporary arrangement of one of As You Like’s songs to survive. The upbeat melodic line with ‘cross-rhythms introduced into the refrain’ is a perfect match with the cross-hatched moods of the play.51 Mortality thrums beneath joy. Life is but a flower. Musical time underscores human time and gives it an eternal dimension. Touchstone teases the boy singers that their note was very untuneable,’ but the elder page stands firm, ‘You are deceived, sir; we kept time, we lost not our time.’ Lovers triumph by keeping time through music which persists as long as there are singers to sing. As You Like It’s songs seem to float in time. They are not specially associated with individual characters but linger in the mind, subtly reprising the play’s deepest themes about human love, both melancholy and jubilant. Though Rosalind thinks romantic love may be evanescent, mere folly, she does believe that human love can survive.

As organising genius of the outcome of the four love pairings in the play, Rosalind keeps the final denouement under her strict control.

| Rosalind | I have promised to make all this matter even. Keep you your word, O Duke, to give your daughter, You yours, Orlando, to receive his daughter. Keep you your word, Phebe, that you’ll marry me, Or else, refusing me, to wed this shepherd. Keep your word, Silvius, that you’ll marry her If she refuse me; and from hence I go To make these doubts all even.52 |

Abandoning her usual springy, colloquial prose for the formality of blank verse in the buildup to one of life’s most ritualistic moments, Rosalind leaves the stage, apparently to step out of role as Ganymede and return in a wedding dress. But Shakespeare makes this deliberately vague. Rosalind could return still dressed as Ganymede, as Rebecca Hall did in 2003. Or she could reappear, not in wedding white which only came in with the Victorians, but as Rosalynde did in Shakespeare’s source novelette by Thomas Lodge, in ‘a gown of green, with kirtle of rich sandal [light silk], so quaint [elegant], that she seemed like Diana in the forest; upon her head she wore a chaplet of roses, which gave her such a grace that she looked like Flora perked in the pride of all her flowers.’53 In whatever costume she chooses, Shakespeare’s Rosalind is perked in all her pride for her official marriage with Orlando. Picking monosyllables for absolute clarity, she expresses her free choice and profound love.

| Rosalind [to Duke Senior] | To you I give myself, for I am yours. |

| [to Orlando] | To you I give myself for I am yours. |

| Duke Senior | If there be truth in sight, you are my daughter. |

| Orlando | If there be truth in sight, you are my Rosalind. |

| Phebe | If sight and shape be true, Why then, my love adieu. |

| Rosalind [to Duke Senior] | I’ll have no father, if you be not he. |

| [to Orlando] | I’ll have no husband, if you be not he. |

| [to Phebe] | Nor ne’er wed woman, if you be not she.54 |

After the verbal fireworks of cross-gender courtship, Rosalind’s simple avowals drop into my mind with emotion too deep for tears. Love is the heartbeat. She chooses a good man’s love’ and needs no father to give her away. Instead, the master-mistress of herself, she says with autonomy, ‘To you I give myself for I am yours.’ Michelle Terry who played Rosalind at Shakespeare’s Globe during summer 2015 observes, she can only become a daughter, become a wife because by the end of the play, the patriarchy has been completely dismantled. She’s re-negotiated the terms.’ At the end of the play, the older ducal generation does not return to government. Instead, Rosalind and Orlando will be the new rulers at court, as well as more equal partners in their enlightened marriage.

What’s radical about Rosalind is that in 1599, and in every production since, she makes love to the man instead of waiting for the man to make love to her – a piece of natural history,’ observed George Bernard Shaw, ‘which has kept Shakespeare’s heroines alive, whilst generations of properly governessed young ladies, taught to say “No” three times at least, have miserably perished.’55 Shaw’s preferred choice for Rosalind’s wedding outfit was the ‘rational dress’ of unisex cycling culottes of the 1890s, an inspired fashion statement for Shakespeare’s most rational and ardent comic heroine.

As You Like It parades a quartet of relationships along the spectrum of human love: Rosalind and Orlando, Silvius and Phebe, Celia and Oliver, and Touchstone and Audrey. They culminate in four unconventional weddings, the most in any of Shakespeare’s plays. ‘All four couples have gone through their own negotiation,’ says Michelle Terry. The love between Rosalind and Orlando is the most debated and the most tested of the four couples. It’s an ideal love because it has no blinkers. It’s gloves off love. Celia and Oliver’s love is a reflection of Rosalind and Orlando’s because, like theirs, it’s fired by love at first sight, and their mutual attraction is built on the same complementary bonds of class and temperament. Phebe settles for Silvius when she realises she can’t marry the boy Ganymede. If Shakespeare was writing today in the era of same sex marriages, Phebe’s story might have a different ending. Silvius’s love for Phebe is unrealistic and unrequited but also a testament to true fidelity. Their future happiness depends on his capacity to forgive Phebe for lusting after Ganymede, and her aptitude to learn about ‘a good man’s love.’ Touchstone and Audrey are in lust with each other and will stay together, while physical passion survives – which may be longer than cynics suggest. Michelle Terry says, ‘I have hope for all of them.’56

There are many demonstrations of human love in As You Like It. The ideal of sisterly love that Celia offers cousin Rosalind offsets the fraternal hatred between Oliver and Orlando, and between the two dukes. That hostility between brothers is redeemed by conversion and forgiveness. Orlando’s attraction to the erotic boy Ganymede still holds a distinct homoerotic frisson, as it would have done in 1599 when a boy played Rosalind. Phebe’s infatuation with Ganymede underlines this. There’s no way of knowing whether we see, even remotely, a similar performance of sexuality that As You Like It’s first audience saw in 1599. But the love between Orlando and old Adam, master and servant, boss and employee, teenager and senior citizen though rare, is recognizable to modern people. It stands proxy for the almost complete lack of parental or filial love in the play. There are no living or loving mothers and the two Dukes’ feelings for their daughters, Rosalind and Celia, appear at best attenuated. Nevertheless, Duke Senior exhibits paternal love and care for his courtiers in the forest who have shown him enough loyalty to share his exile. Perhaps they have become his substitute family. His real paternity is restored when lost daughter Rosalind finally unmasks herself to him.

With her own special wisdom, Rosalind fundamentally prefers reality to romance. Her comic, anarchic view of love is sharpened by her combination of emotional depth with a constant edge of doubt and cynicism. We recognise the authenticity of her love today as they recognised it in 1599. Her approach to love is for our times as well as for hers. Wherever love is to be found is more important than whatever gender one is. Rosalind’s aim is more equal love between lovers, a fulfilling emotional life of conversation with Orlando, coupled with the responsibility of principled government over a ‘land itself at large, a potent dukedom.’ Romantic love is only one of the vital components in Rosalind’s life plan. In 1599, the sacred rite of marriage ennobled the play’s four couplings, and pre-eminently the union of Rosalind and Orlando. Hymen, a gender-free celebrant, sings the final song.

| Wedding is great Juno’s crown, | |

| O blessed bond of board and bed. | |

| ’Tis Hymen peoples every town, | |

| High wedlock then be honoured. | |

| Honour, high honour and renown | |

| To Hymen, god of every town.57 |