He pulls up, lights flashing red-white-and-blue, and Hannah hurries into the front seat, McCluskey wrapping his big arms around her, his jacket several yards of cheap cloth smelling of chewing gum, smoke, and baby powder, and as they head out of the city, lights no longer flashing, she starts telling him the story of 1982, only the second time she’s told it to anyone, her former editor Max Reagan the first time, a Newark bar thick with smoke, and now she’s telling McCluskey about Matthew Weaver in the half-light of the Lincoln Tunnel, taillights bouncing from white tiles, their glow like red flares sailing over the ceiling and walls, and when she reaches the part about the tree and the rope, they emerge from the darkness, soaring into the widening New Jersey sky, the story building to its finale, that Red Ryder BB gun, the sting of the pellets over and over, a pain like being punched in the eye, and then darkness.

And though she doesn’t tell him everything, doesn’t tell him what she did that day and weeks before, she tells him enough, McCluskey driving in silence, his knuckles whitening on the black steering wheel.

Goddammit, Aitch, why didn’t you say something? he shouts, hitting the dash, and quickly apologizing, Sorry, Hannah, sorry, I’m not yelling at you, I’m not, it’s just, this damn fuckin world.

Why would I have told you? she says. What difference would it have made?

McCluskey doesn’t say anything, doesn’t know what to say.

Then she starts talking about Patrick, Patch the twelve-year-old boy, Matthew’s buddy, how she thought he wasn’t there, not right there, how she thought he had saved her, only saved her, and then she tells McCluskey what she just saw on her husband’s computer screen, and that she didn’t read everything, but she read enough, enough to know he was there … only half a scream … the way her head twisted despite the rope tied around her neck … more than enough to know he could have stopped it all, and that their marriage, their entire life together, is based on a lie.

Back in their apartment, she had made sure to leave it open on his computer, For Dr. Rosenstock, one line highlighted … Hannah’s eye socket looked like it was housing a dark smashed plum … so he will see it when he gets home.

She could look at the thing now, she could read everything Patch had to say for himself on her phone, because almost an hour ago, when she read more than she could bear, after crying a little more with every word, she had copied it, the whole thing, fingers shaking, command A, command C, and sent it to herself, her work email, all of the words (how much did he write?), before running out of the apartment, running to the café across Seventh Avenue, and waiting for him to arrive, flashing red-white-and-blue, red-white-and-blue.

And they reach Pulaski Skyway, and there’s nothing more she wants to tell.

Aitch, I’m sorry, that’s the worst fuckin thing I ever heard in my life.

Nah, McCluskey, you’re a cop. I mean, it’s not like anyone died or anything, she says, and then shudders as she realizes this isn’t true, so that when her phone starts to ring, the sound startles her.

Is it him? says McCluskey.

No, she says, feeling a sense of relief as she looks at the screen. Just Jen again, she says, turning the phone over, dropping it into her lap. Not now, Jen, she whispers, letting the call drop to voice mail.

Christ, I don’t know what to say, Aitch. I don’t know what to say about any of it. Like, this Matthew, what happened to that sick little fuck?

They locked him up, she says. After that, who knows?

And your husband—how old you say he was when this happened?

Thirteen. No, wait, I was thirteen. I guess he was twelve.

But still. Just standing there? Doing nothing at all?

Right.

And meanwhile he’s telling his therapist all about it, for crying out loud.

Looks that way.

Fuckin asshole. Sorry, Aitch, sorry, it’s not my place …

And then Hannah’s phone makes a sound, a new message.

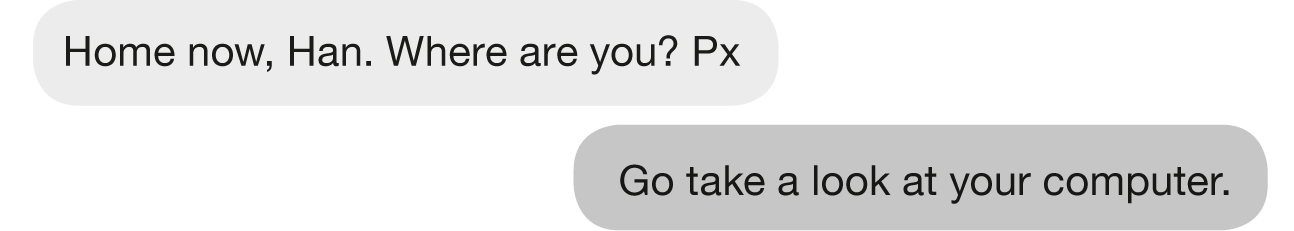

And knowing he will try to call her in thirty seconds, a minute max, she taps out another message …

![]()

… presses SEND, powers off.