CHAPTER

19

Diseases of the Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat

National EMS Education Standard Competencies

Medicine

Integrates assessment findings with principles of epidemiology and pathophysiology to formulate a field impression and implement a comprehensive treatment/disposition plan for a patient with a medical complaint.

Diseases of the Eyes, Ears, Nose, and Throat

Knowledge of the anatomy, physiology, epidemiology, pathophysiology, psychosocial impact, presentations, prognosis, and management of

Common or major diseases of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat, including nose bleed (pp 1094–1102, 1103–1106, 1107–1108, 1110–1115)

Common or major diseases of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat, including nose bleed (pp 1094–1102, 1103–1106, 1107–1108, 1110–1115)

Knowledge Objectives

1. Explain facial anatomy and relate physiology to facial injuries. (pp 1091–1092, 1102, 1106, 1108–1110)

2. Differentiate between the following types of facial injuries, highlighting the defining characteristics of each:

a. Eye (pp 1094–1102)

b. Ear (pp 1103–1106)

c. Nose (pp 1107–1108)

d. Throat (pp 1110–1115)

e. Mouth (pp 1110–1115)

3. Explain the pathophysiology of eye injuries. (pp 1094–1102)

4. Relate assessment findings associated with eye injuries and disorders to pathophysiology. (pp 1094–1102)

5. Integrate pathophysiologic principles to the assessment of a patient with an eye injury or eye disorder. (pp 1092–1102)

6. Formulate a field impression for a patient with an eye injury based on the assessment findings. (pp 1092–1094)

7. Develop a patient management plan for a patient with an eye injury based on the field impression. (pp 1092–1094)

8. Explain the pathophysiology of ear injuries and disorders. (pp 1103–1106)

9. Relate assessment findings associated with ear injuries and disorders to pathophysiology. (pp 1102–1106)

10. Integrate pathophysiologic principles to the assessment of a patient with an ear injury. (pp 1102–1106)

11. Formulate a field impression for a patient with an ear injury based on the assessment findings. (pp 1102–1106)

12. Develop a patient management plan for a patient with an ear injury based on the field impression. (pp 1102–1106)

13. Explain the pathophysiology of nose injuries and disorders. (pp 1107–1108)

14. Relate assessment findings associated with nose injuries and disorders to pathophysiology. (pp 1106–1108)

15. Integrate pathophysiologic principles to the assessment of a patient with a nose injury. (pp 1106–1108)

16. Formulate a field impression for a patient with a nose injury based on the assessment findings. (pp 1106–1108)

17. Develop a patient management plan for a patient with a nose injury based on the field impression. (pp 1106–1108)

18. Explain the pathophysiology of throat and mouth injuries and disorders. (pp 1110–1115)

19. Relate assessment findings associated with throat and mouth injuries and disorders to pathophysiology. (pp 1108–1115)

20. Integrate pathophysiologic principles to the assessment of a patient with a throat or mouth injury. (pp 1108–1115)

21. Formulate a field impression for a patient with a throat or mouth injury based on the assessment findings. (pp 1108–1115)

22. Develop a patient management plan for a patient with a throat or mouth injury based on the field impression. (pp 1108–1115)

Skills Objectives

There are no skills objectives for this chapter.

Introduction

Introduction

Disorders of the eye, ear, nose, and throat (EENT) are becoming more of an issue for emergency personnel. Paramedics may respond to calls that involve these important structures.

A significant number of calls for EMS involving EENT structures are a result of trauma; such injuries will be discussed in the chapter, Face and Neck Trauma. This chapter covers medical conditions that could result in a call to 9-1-1, or which you could notice when you are assessing a patient who called 9-1-1 for an unrelated reason. On such calls, familiarity with these conditions will help you during assessment of the patient. Knowledge of these conditions also allows you the opportunity to educate the patient on prevention or potential care for a condition that the patient may have.

Oftentimes, when you encounter a patient with an EENT disorder, it makes sense to transport the patient possibly to an emergency department with access to an eye specialist or an ear, nose, and throat specialist for further evaluation. For example, any time an object is lodged in the eye, ear, nose, or throat, the patient must receive transport.

This chapter begins by discussing general considerations when you are assessing a patient with a complaint related to conditions of the eyes, ears, nose, and throat. You will also learn about specific conditions and their field treatment, if any.

The Eye

The Eye

Every year, more than 2.5 million Americans sustain eye injuries that require medical attention. Some of the emergencies associated with eye disease include glaucoma, macular degeneration, and diabetic retinopathy. Usually patients having these diseases have a long-standing history of an underlying condition that predisposes them to the disorder (comorbidity). From a standpoint of mortality, incidence is low.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye

Anatomy and Physiology of the Eye

The globe, or eyeball, is a spherical structure measuring about 1 inch in diameter that is housed within the eye socket, or orbit.

Special Populations

According to the CDC, vision disability is one of the top 10 disabilities among children.

In the geriatric population, you are likely to encounter patients who have undergone laser-assisted eye surgery (lasik surgery). Lasik surgery uses a special laser to slice a flap in the cornea and adjust the shape of the middle section of the cornea (stroma). This surgery can reduce the need for corrective lenses. The latest techniques can be done without the “flap” in the cornea. Immediately following the surgery and for the next few weeks, patients are instructed to not let air blow directly into their eyes and wear goggles while they sleep so they do not scratch their cornea. Geriatric patients are also more likely to undergo cataract surgery and eye surgery for glaucoma.

Older people may also experience eye injuries from falls. Eye conditions and problems are part of the list of comorbid factors simultaneously occurring in the geriatric population. Diabetic retinopathy affects one third of those older than 40 years who have diabetes mellitus.

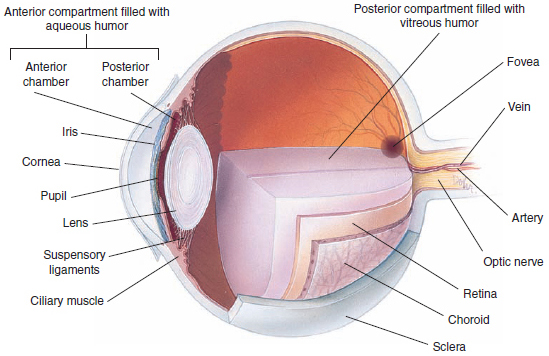

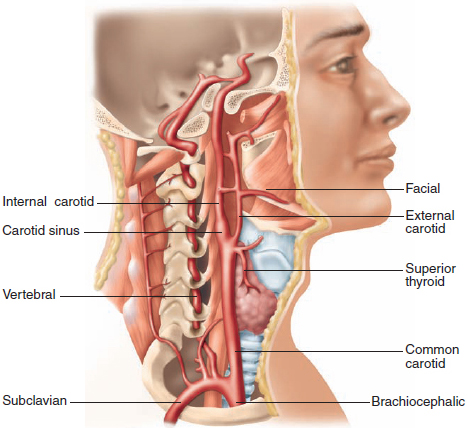

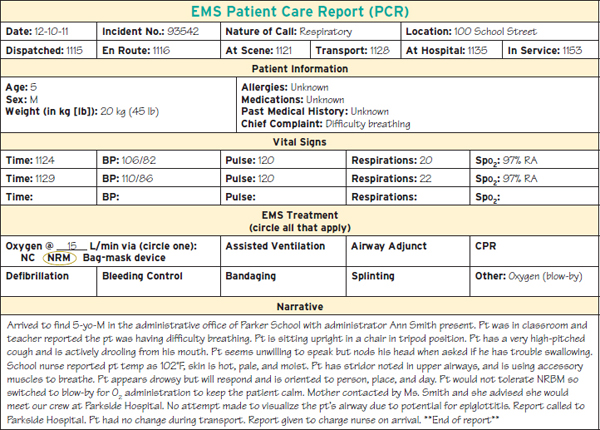

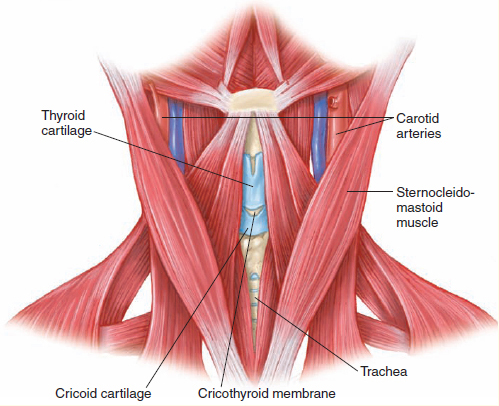

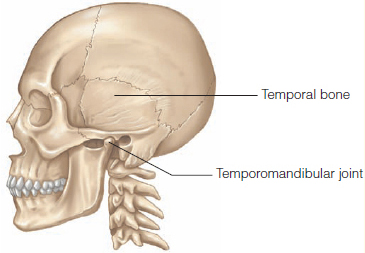

The eyes are held in place by loose connective tissue and several muscles. These muscles also control eye movements. The oculomotor nerve (third cranial nerve) innervates the muscles that cause motion of the eyeballs and upper eyelids. It also carries parasympathetic nerve fibers that cause constriction of the pupil and accommodation of the lens. The optic nerve (second cranial nerve) provides the sense of vision Figure 1.

The structures of the eye include the following:

The sclera (“white of the eye”) is a tough, fibrous coat that helps maintain the shape of the eye and protect the contents of the eye. In some illnesses, such as hepatitis, the sclera becomes yellow (icteric) from staining by bile pigments.

The sclera (“white of the eye”) is a tough, fibrous coat that helps maintain the shape of the eye and protect the contents of the eye. In some illnesses, such as hepatitis, the sclera becomes yellow (icteric) from staining by bile pigments.

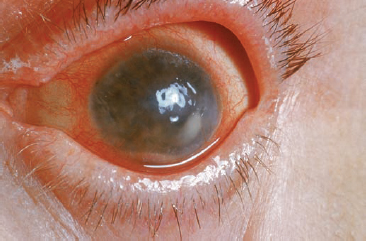

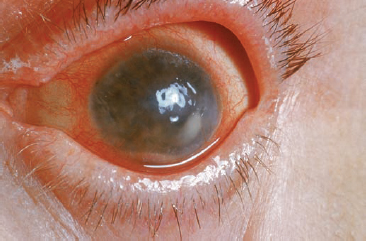

The cornea is the transparent anterior portion of the eye that overlies the iris and pupil. Clouding of the cornea during aging results in a condition known as cataract.

The cornea is the transparent anterior portion of the eye that overlies the iris and pupil. Clouding of the cornea during aging results in a condition known as cataract.

The conjunctiva is a delicate mucous membrane that covers the sclera and internal surfaces of the eyelids but not the iris. Cyanosis can be detected in the conjunctiva when it is not easily assessed on the skin of dark-skinned patients.

The conjunctiva is a delicate mucous membrane that covers the sclera and internal surfaces of the eyelids but not the iris. Cyanosis can be detected in the conjunctiva when it is not easily assessed on the skin of dark-skinned patients.

The iris is the pigmented part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. It consists of muscles and blood vessels that contract and expand to regulate the size of the pupil.

The iris is the pigmented part of the eye that surrounds the pupil. It consists of muscles and blood vessels that contract and expand to regulate the size of the pupil.

The pupil is the circular adjustable opening within the iris through which light passes to the lens. A normal pupil dilates in dim light to permit more light to enter the eye and constricts in bright light to decrease the light entering the eye.

The pupil is the circular adjustable opening within the iris through which light passes to the lens. A normal pupil dilates in dim light to permit more light to enter the eye and constricts in bright light to decrease the light entering the eye.

Behind the pupil and iris is the lens, a transparent structure that can alter its thickness to focus light on the retina at the back of the eye.

Behind the pupil and iris is the lens, a transparent structure that can alter its thickness to focus light on the retina at the back of the eye.

The retina, which lies in the posterior aspect of the interior globe, is a delicate, 10-layered structure of nervous tissue that extends from the optic nerve. It receives light impulses and converts them to nerve signals that are conducted to the brain by the optic nerve and interpreted as vision.

The retina, which lies in the posterior aspect of the interior globe, is a delicate, 10-layered structure of nervous tissue that extends from the optic nerve. It receives light impulses and converts them to nerve signals that are conducted to the brain by the optic nerve and interpreted as vision.

YOU are the Medic PART 1

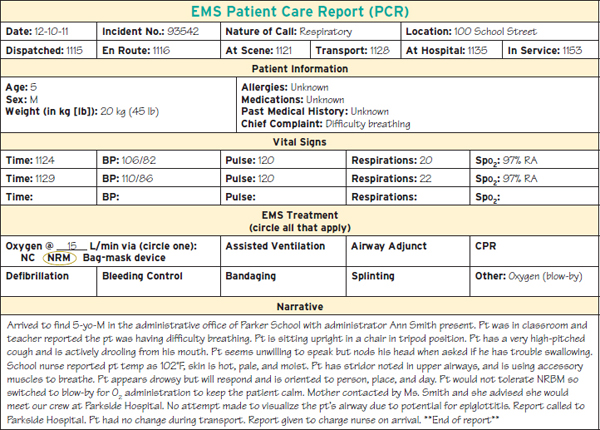

You are dispatched to a local school for a child with a sore throat. It is very cold outside and you are wondering what prompted this call to 9–1–1. When you arrive on scene, you are directed to the administrative office. You and your partner enter the office to see a small child, approximately 5 years old. The child is sitting upright and leaning slightly forward. He is breathing through his mouth and looks very sick. The administrator says they are trying to contact the child’s parents and that the school nurse took the child’s temperature, which was 102° F.

1. What is your primary concern after scene safety is established?

2. Do you have concerns that the patient’s parents have not been contacted?

Figure 1 The structures of the eye.

The anterior chamber is the portion of the globe between the lens and the cornea. It is filled with aqueous humor, a clear watery fluid. If aqueous humor is lost through a penetrating injury to the eye, it will gradually be replenished.

The posterior chamber is the portion of the globe between the iris and the lens that is filled with vitreous humor, a jellylike substance that maintains the shape of the globe. If vitreous humor is lost, it cannot be replenished, and blindness may result.

Light rays enter the eyes through the pupil and are focused by the lens. The image formed by the lens is cast on the retina, where sensitive nerve fibers form the optic nerve. The optic nerve transmits the image to the brain, where it is converted into conscious images in the visual cortex.

There are two types of vision: central and peripheral. Central vision facilitates visualization of objects directly in front of you and is processed by the macula, the central portion of the retina. The remainder of the retina processes peripheral vision, which enables visualization of lateral objects while a person is looking forward.

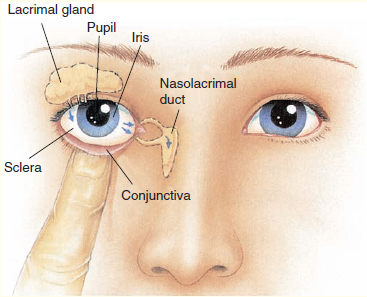

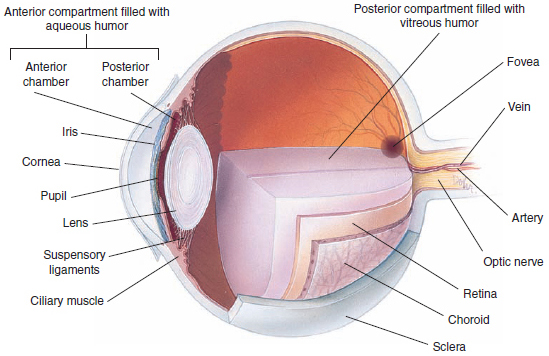

The lacrimal apparatus secretes and drains tears from the eye. Tears produced in the lacrimal gland drain into lacrimal ducts, then into lacrimal sacs that pass into the nasal cavity via the nasolacrimal duct. Tears moisten the conjunctivae Figure 2.

Patient Assessment

Patient Assessment

Making sure you and other responders are safe from the many hazards on trauma scenes, and the often hidden dangers on medical scenes, should stand first in your order of priorities. Fear and panic from loss of vision can cause dangerous and bizarre behavior in your patient. Keep your patient calm. The scene size-up is an opportunity to discover clues to the cause of the complaint, while avoiding potential hazards.

As you form a general impression of the patient, note environmental clues at the scene, the approximate age and sex of the patient, and his or her degree of distress. Do not let the high degree of distress or concern over the potential visual impairment sidetrack your observations of the scene and those dangers that may have caused an injury or condition.

Figure 2 The lacrimal system consists of tear glands and ducts. Tears act as lubricants and keep the anterior part of the eye from drying.

Primary assessment of airway and breathing should take precedence, as should ruling out any life threats. Do not be distracted by a swollen, irritated, or deformed eye to the extent that you bypass the highest priorities. You must ensure that the patient has an open and adequate airway, that the patient is breathing, that there are no threats to ventilation, and that the patient has an adequate pulse. Ensure that there are no life threats to circulation that need your immediate attention.

Depending on the severity of the eye condition, an early transport decision to the right facility can improve outcomes. Level 1 trauma centers have the skilled services necessary to treat a serious eye problem. Covering both eyes can limit damage to the affected eye. Consider pain management and, if necessary, mild sedation during transport.

Cardiac monitoring is recommended. Ocular pressure can stimulate the vagus nerve, and a vagal response in your patient. Eye drops and eye medication can cause side effects such as low or high blood pressure.

Your demeanor should be supportive and calm. Remember, a patient facing potential long-term vision loss will need emotional care as well; this can be a life-changing event for your patient.

Obtain the chief complaint from the patient and begin to elaborate on it using OPQRST. When you are obtaining the history, determine how and when the symptoms began, and what symptoms the patient is experiencing. Are both eyes affected? Does the patient have any underlying diseases or conditions of the eye (such as glaucoma)? Does the patient take medications for his or her eyes? Diabetes is the leading cause of new cases of blindness in adults according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). One in three of diabetic adults older than 40 years has a disease called diabetic retinopathy. Forty-two million adults have diabetic retinopathy, and 655,000 have vision alteration due to this condition. Diabetic retinopathy affects the small blood vessels in the retina. Vision disturbances can include blurred vision, floaters, blind spots, or blindness.

A variety of symptoms may indicate a serious ocular condition:

Visual loss that does not improve when the patient blinks is an important symptom. It may indicate damage to the globe or to the optic nerve.

Visual loss that does not improve when the patient blinks is an important symptom. It may indicate damage to the globe or to the optic nerve.

Double vision usually points to trauma involving the extraocular muscles, such as a fracture of the orbit.

Double vision usually points to trauma involving the extraocular muscles, such as a fracture of the orbit.

Severe eye pain is a symptom of a significant eye injury.

Severe eye pain is a symptom of a significant eye injury.

A foreign body sensation usually indicates superficial injury to the cornea or the presence of a foreign object trapped behind the eyelids.

A foreign body sensation usually indicates superficial injury to the cornea or the presence of a foreign object trapped behind the eyelids.

Assessment of specific eye conditions begins with a thorough examination to determine the extent and nature of the situation. Always perform your examination using standard precautions, taking great care to avoid aggravating the affected area. Be sure to assess for pain or tenderness, swelling, abnormal or loss of movement, sensation changes, circulatory changes, deformity, visual changes, and airway compromise.

Physical examination of the eyes includes assessment of the visible ocular structures, as well as ocular function. This evaluation is shown in the chapter, Patient Assessment. Assess the ocular structures for the following:

Orbital rim: for ecchymosis, swelling, lacerations, and tenderness

Orbital rim: for ecchymosis, swelling, lacerations, and tenderness

Eyelids: for ecchymosis, swelling, lacerations, or any abnormalities

Eyelids: for ecchymosis, swelling, lacerations, or any abnormalities

Corneas: for foreign bodies

Corneas: for foreign bodies

Conjunctivae: for redness, pus, inflammation, and foreign bodies

Conjunctivae: for redness, pus, inflammation, and foreign bodies

Globes: for redness, abnormal pigmentation, and lacerations. Inspect the eye surface for growths, discoloration, and differences between the eyes.

Globes: for redness, abnormal pigmentation, and lacerations. Inspect the eye surface for growths, discoloration, and differences between the eyes.

Pupils: for size, shape, equality, and reaction to light. Note whether they are symmetric.

Pupils: for size, shape, equality, and reaction to light. Note whether they are symmetric.

When you are assessing ocular function, perform the following:

Visual acuity. Assess the patient’s ability to see large and small letters, for example by reading the writing on a prescription bottle, or by using a hand-held visual acuity chart such as the Snellen chart (shown in the chapter, Patient Assessment). Test each eye separately and document the results.

Visual acuity. Assess the patient’s ability to see large and small letters, for example by reading the writing on a prescription bottle, or by using a hand-held visual acuity chart such as the Snellen chart (shown in the chapter, Patient Assessment). Test each eye separately and document the results.

Peripheral vision. Evaluate the peripheral vision by testing the ability to recognize an object entering the extremes of the visual field (confrontation).

Peripheral vision. Evaluate the peripheral vision by testing the ability to recognize an object entering the extremes of the visual field (confrontation).

Ocular motility. Check the ability to move the eyes in all directions. Check for paralysis of gaze or discoordination between the movements of the two eyes (dysconjugate gaze).

Ocular motility. Check the ability to move the eyes in all directions. Check for paralysis of gaze or discoordination between the movements of the two eyes (dysconjugate gaze).

In addition to the physical examination, during the secondary assessment you should obtain a full set of baseline vital signs.

During reassessment, vital signs should be monitored every 5 to 15 minutes depending on the severity of the patient’s condition. Continuing assessment allows you to track any trends that may be occurring.

Note that a patient may experience more side effects if he or she uses multiple eye medications. Also, if a patient uses too much of one or several medications, he or she may experience side effects because the medication can enter the bloodstream via the nasolacrimal system, which serves the function of draining tears. Side effects can be systemic if enough medication enters the bloodstream.

Ask patients how they administered their eye medications. Sometimes part of the problem is that the patient did not follow the instructions for the specific medication, ie, it is usually recommended to wait approximately 5 minutes between administering the first and second drop. Of course, this 5-minute rule does not apply to emergency measures such as administering tetracaine prior to inserting a Morgan lens.

There are many medications to address a variety of eye problems. Eye drops can be used for conjunctivitis, dry eyes, red eyes, eye pain, glaucoma, eye surgery, herpes simplex, itchy eyes, and corneal abrasions. Eye lubricants are available for protecting eyes that do not produce tears (as a result of seventh nerve damage). Eye drops and lubricants are most often applied by gently squeezing the lower eyelid to make a pouch and applying the medicine into the lower lid. The patient then should close his or her eyes and roll the eyes downward with eyes closed. Gentle pressure should be applied to the corner of the eyes to prevent drainage of the medicine from the eye. Irrigation of the eyes may be necessary for chemical burns or thermal burns. Treatment consists of irrigating the eye with sterile water or isotonic saline solution, flushing the liquid from the inside corner to the outside of the eye, except when a Morgan lens is being used (described below). Eye injuries should be seen in the emergency department. Children may need to be treated under anesthesia. Many eye injuries will need a topical anesthetic and antibiotic, which is not generally performed by a paramedic.

Words of Wisdom

Anisocoria, a condition in which the pupils are not of equal size, is a significant finding in patients with ocular injuries or closed head trauma. However, simple or physiologic anisocoria occurs in approximately 20% of the population. Therefore, about one person out of five has some degree of difference in the sizes of their pupils. Usually, the patient’s pupils differ in size by less than 1 mm; however, approximately 4% of people have pupils that vary in size by more than 1 mm. This is not a clinically significant finding.

Unilateral cataract surgery may also cause inequality of pupil size. The pupil of the eye affected by the cataract will be nonreactive to light.

Eye injuries may be irreversible, and patients may or may not be aware of the seriousness of the event. Patients may exhibit denial, anger, fear, hysteria, and depression. Communication is key to keeping your patient calm and informed. Remember that early decisions to transport to the appropriate facility can improve outcomes in some patients, and early communication with a medical control physician can help direct your care and help with transport decisions.

Words of Wisdom

When patients ask you what you think is wrong, remember you are serving them. Remind them that you do not have definitive answers and that you are not a physician, but tell them what you think is going on. Be honest and sincere about what you are telling them, with the goal of keeping your patient both informed and calm.

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Specific Conditions

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Specific Conditions

Burns of the Eye and Adnexa

Burns to the eye account for somewhere between 7% and 15% of eye injuries. Chemicals, heat, and light rays can all burn the delicate tissues of the eye and adnexa (the surrounding structures and accessories), often causing permanent damage. Your role is to stop the burning process and prevent further damage.

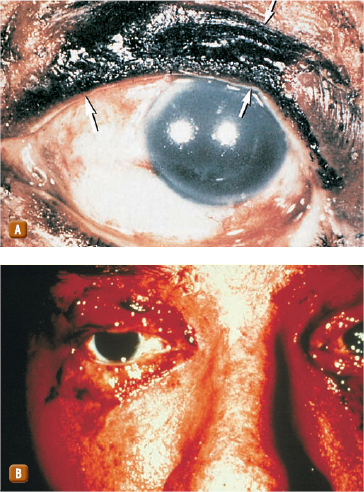

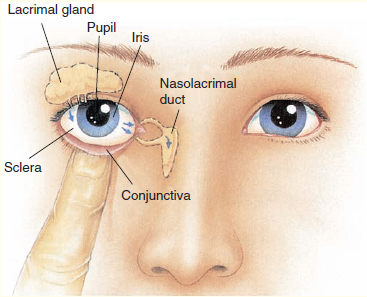

Thermal burns occur when a patient is burned in the face during a fire, although the eyes usually close rapidly because of the heat. This reaction is a natural reflex to protect the eyes from further injury. However, the eyelids remain exposed and are frequently burned Figure 3.

Infrared rays, eclipse light (if the patient has looked directly at the sun), and laser burns can cause significant damage to the sensory cells of the eye when rays of light become focused on the retina. Retinal injuries that are caused by exposure to extremely bright light are generally not painful but may result in permanent damage to vision.

Superficial burns of the eye can result from ultraviolet rays from an arc welding unit, prolonged exposure to a sunlamp, or reflected light from a bright snow-covered area (snow blindness). This kind of burn may not be painful initially but may become so 3 to 5 hours later, as the damaged cornea responds to the injury. Severe conjunctivitis usually develops, along with redness, swelling, and excessive tear production.

Assessment and Management Eye injuries are a substantial distracting injury. If the mechanism of injury suggests a high index of suspicion for a spinal injury, all spinal precautions must be followed. Spine and head stabilization may be necessary, as well as correcting any life threats. Assessment may be difficult because the patient may be forcibly keeping his or her eyes closed. You will need to gain the patient’s trust and open the lid to irrigate the eye with sterile water or saline solution. You may not be able to adequately assess the patient’s eye until the pain has been managed. When full examination is possible, assessment should include checking whether the eye can move to the following six cardinal positions of gaze: right, right up, right down, left, left up, and left down (following in a Z or H pattern). Assessment should also include checking pupil dilation to light, and checking the patient’s vision when he or she looks to the left and to the right. Peripheral vision can be checked by having patients look straight ahead while you provide motion at the extreme left and right of their view. You can move your hand into the field of vision, from beyond the field of vision, asking the patient to acknowledge when he or she sees your hand. The chapter, Patient Assessment shows how to perform an eye examination with an ophthalmoscope. Finally, document all changes.

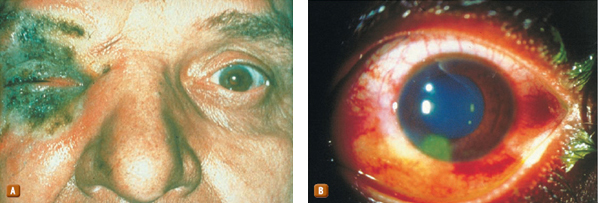

Figure 3 Thermal burns occasionally cause significant damage to the eyelids. A. Arrows show some full-thickness burns. B. Burns of the eyelids require immediate hospital care.

Burns to the eye that are caused by ultraviolet light are most effectively treated by covering the eye with a sterile, moist pad and an eye shield. The application of cool compresses lightly over the eye may provide some pain relief if the patient is in extreme distress. Place the patient in a supine position during transport, and protect the patient from further exposure to bright light.

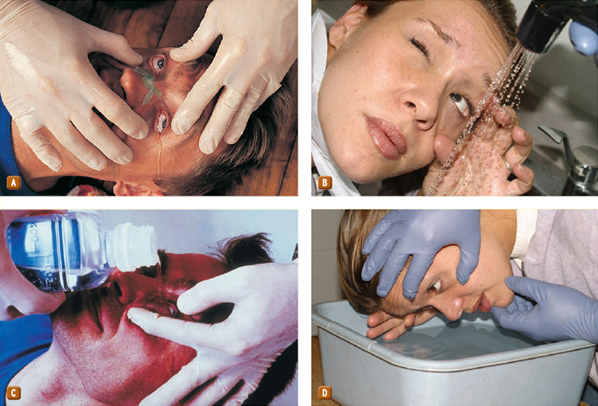

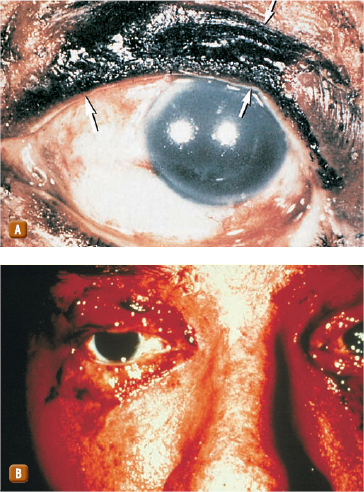

Chemical burns, which are usually caused by acid or alkali solutions, require immediate emergency care because they can rapidly lead to blindness Figure 4 The most important prehospital treatment in such cases is to begin immediate irrigation with sterile water or saline solution. Never use any chemical antidotes (such as vinegar, baking soda) when you are irrigating the patient’s eye; use sterile water or saline only.

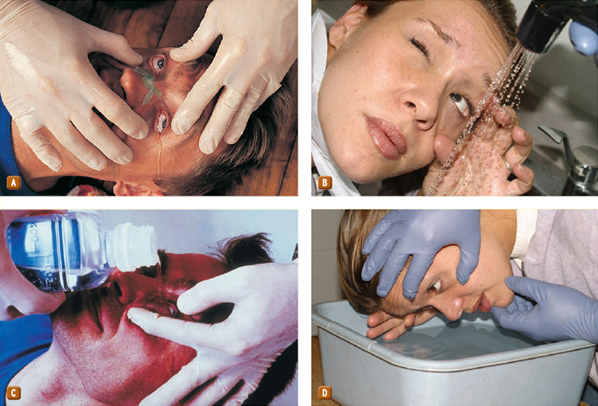

The goal when you are irrigating the eye is to direct the greatest amount of solution or water into the eye as gently as possible. Because opening the eye spontaneously may cause the patient pain, you may have to force the lids open to irrigate the eye adequately. Ideally, you should use a bulb or irrigation syringe, a nasal cannula, or some other device that will allow you to control the flow Figure 5. In some circumstances, you may have to pour water into the eye by holding the patient’s head under a gently running faucet. You can have the patient immerse his or her face in a large pan or basin of water and rapidly blink the affected eyelid. If only one eye is affected, take care to avoid contaminated water getting into the unaffected eye.

Irrigate the eye for at least 5 minutes. If the burn was caused by an alkali or a strong acid, irrigate the eye continuously for 20 minutes because these substances can penetrate deeply. One common possibility occurs where anhydrous ammonia is used during the process of cooking methamphetamine. If the eyes are not irrigated promptly and efficiently, permanent damage is likely. Whenever you have to irrigate the eye(s), continue to irrigate the eye en route to the hospital if possible.

You may have access to an eye irrigation device called the Morgan lens. The Morgan lens is appropriate for use with eye burns from acids, alkalis, or solvents, and can also be used to help remove a foreign body as long as it is not embedded or impaled in the eye. Follow these steps when you are using a Morgan lens:

1. Administer with a topical anesthetic such as tetracaine (Pontocaine, Dicaine).

2. Connect the Morgan lens to the bag of IV fluid of choice: 0.9% saline, lactated Ringer’s, or sterile water and let it begin to drip.

3. Pull tension on the upper eyelid and slide the Morgan lens under the upper eyelid.

4. Cup the lower eyelid and slide the Morgan lens under the lower eyelid.

5. Run the fluid at the desired rate.

6. Continue to run the fluid while the Morgan lens is in place. Do not stop the fluid.

YOU are the Medic PART 2

Your patient feels very hot to the touch. While your partner is obtaining vital signs, you ask the administrator if she could provide any information as to what happened to the patient. She states that the patient’s teacher said that he was leaning forward and drooling like he was going to vomit. She also says the patient has been coughing and it “sounds funny.” She says the child’s name is Jimmy.

Recording Time: 0 Minutes |

|

Appearance |

Awake |

Level of consciousness |

Alert (oriented to person, place, and day) but is drowsy |

Airway |

Open |

Breathing |

Sounds obstructed |

Circulation |

Adequate |

3. What do you need to know about the patient’s cough?

4. What steps will you take in your further assessment of this patient?

Figure 4 A. Chemical burns typically occur when an acid or alkali is splashed into the eye. B. A chemical burn from lye, an alkaline solution.

Figure 5 Four ways to effectively irrigate the eye. A. Nasal cannula. B. Shower. C. Bottle. D. Basin. Always protect the uninjured eye from the irrigating solution to prevent exposure to the substance.

The Morgan lens should generally not be removed in the field. It is best to use the lens with continuous fluid until arrival at the emergency department where a physician can consider use of an eye lubricant and removal of the lens.

Transport considerations for eye burn patients include preventing one eye from draining into the unaffected eye, which would contaminate it. If irrigation is in progress, the unaffected eye should be in a protected position. Specialized treatment and care for burns to the eyes can be found at level 1 trauma centers.

You may encounter patients who wear contact lenses. In general, if the eye is injured, you should not attempt to remove contact lenses because you may further aggravate the injury. The only indication for removing contact lenses in the prehospital setting is a chemical burn of the eye. In this situation, the lens can trap the offending chemical and make irrigation difficult, thus worsening the injury.

There are three types of contact lenses: hard, rigid gaspermeable, and soft (hydrophilic). Small, hard contact lenses usually are tinted, making them relatively easy to see. Large, soft contact lenses are clear and can be difficult to see, even more so if they “float” up or down under an eyelid.

To remove a hard contact lens, use a small suction cup, moistening the end with saline Figure 6A. To remove soft lenses, place one to two drops of saline in the eye Figure 6B, gently pinch the lens between your gloved thumb and index finger, and lift it off the surface of the eye Figure 6C. Place the contact lens in a container with sterile saline solution. Always advise emergency department staff if a patient is wearing contact lenses.

Occasionally, you may care for a patient who is wearing an eye prosthesis (artificial eye). You should suspect an eye of being artificial when it does not respond to light, move in concert with the opposite eye, or appear quite the same as the opposite eye. If you are unsure as to whether the patient has an eye prosthesis, ask the patient. No harm will be done if you care for an artificial eye as you would a normal one; however, you should make every attempt to accurately determine the patient’s eye function.

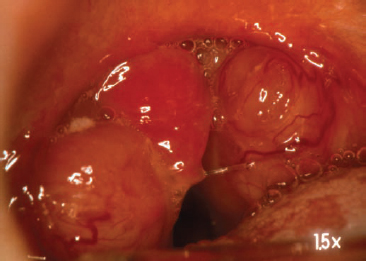

Conjunctivitis

Conjunctivitis or “pink eye” is a condition where the conjunctiva becomes inflamed and red Figure 7. Conjunctivitis most often starts in one eye and spreads to the other eye. The conjunctiva is a thin layer that lines the inside of the eyelids and the white part of the eye. Inflammation causes the white part of the eye to take on a red or pink tint. Most often this is caused by bacteria, viruses, allergies, or foreign bodies present in the eye. Viral and bacterial causes are highly contagious and can become an epidemic. Conjunctivitis accounts for the most absences in daycare or school settings according to the CDC. Allergic conjunctivitis is caused by a trigger or irritating allergen. Viral conjunctivitis is often associated with an upper respiratory virus or cold. Bacterial conjunctivitis is caused by various bacterial infections. Newborns are susceptible to conjunctivitis from sexually transmitted diseases passed on by the mother, irritation to antibiotic eye drops at birth, or an infection from a clogged tear duct. If conjunctivitis is due to a foreign body, the eye will begin to produce tears in an attempt to flush out the object.

Assessment and Management Assessment of the patient’s condition should occur after ruling out any life threats to the patient or dangers to the crew. A general assessment of the patient’s vision should be performed, including assessment of visual acuity, assessment of the external eye, assessment of the pupils, assessment of peripheral vision, and assessment of eye movement, as described earlier.

Figure 6 Removing contact lenses should be limited to patients with chemical burns to the eye. A. To remove hard contact lenses, use a specialized suction cup moistened with sterile saline solution. B. Step 1: To remove soft contact lenses, instill 1 or 2 drops of saline or irrigating solution. Step 2: Pinch off the lens with your gloved thumb and index fingers.

Figure 7 Conjunctivitis is inflammation of the eye. It may be associated with the presence of a foreign object in the eye.

Viral conjunctivitis normally resolves on its own. It can last up to 2 weeks but usually reaches a peak in 3 to 5 days. Bacterial conjunctivitis requires a topical antibiotic in order to heal. Allergic conjunctivitis may need a topical antihistamine prescribed by the physician in the emergency department.

Corneal Abrasion

Abrasions or scrapes to the outer surface of the eye can be quite painful. They are commonly caused by fingernails, paper, and airborne objects from construction activities. Metal filings are particularly inflammatory because they cause a “rust ring” after 24 hours, which must be removed in the hospital.

Corneal abrasions are the most common eye injury seen in emergency departments. They are due to superficial trauma to the cornea, often from a foreign body, but may also be due to excessive rubbing, chemical burns, or being poked in the eye by a finger or makeup brush. If the redness and discomfort does not resolve after an object has been removed, or after the eye has been flushed with water or saline, the patient should be seen in the emergency department and referred to an ophthalmologist if necessary.

Assessment and Management Patients will likely experience significant pain, sensitivity to light (photophobia), and tearing. Close examination of the cornea may reveal a line or scratch. The cornea heals quickly and abrasion sensation may vary. It may feel like a grain of sand in the eye or a stabbing sensation and can promote excessive tearing. It is usually more painful when the injury is exposed to the air. Lubrication with irrigation or a lubricant can alleviate some pain. Taping the injured eyelid closed with paper tape can keep the injured eye from drying out. Examining the eye by inverting the upper and lower eyelids can expose the source of the corneal abrasion. It is important to carefully look for a foreign body in the eye.

A topical anesthetic like tetracaine can relieve some symptoms. Supportive care in the prehospital setting may include irrigation, which may also help remove the object. If the cause of the abrasion is still present, it may need to be removed at an appropriate facility. If movement of the eye causes severe discomfort, it may be necessary to cover both eyes. A lubricant can resolve some of the pain along with closing and covering the injured eye. Taping the eyelid closed with paper tape can allow the patient to relax without forcibly holding the injured eye shut. These injuries, especially those involving metal fragments, may need to be examined under a special microscope. In-hospital treatment consists of removing the fragment (if still present), treating the eye with topical antibiotics, and patching the eye.

Foreign Body

Dust, dirt, splinters, and other particles are commonly involved in eye injuries. Although most are not threatening to sight, they can cause significant pain. Most foreign objects in the eye occur as a result of occupational injury; however, you may also treat patients whose injury is hobby-related.

The use of grinders, sanders, nailers, weed whackers, and other machines commonly cause these injuries. As the machinery is working, it can dislodge and eject particles a long distance, and if safety glasses are not worn, foreign objects can enter the eyes. Foreign objects in the eye can also be due to auto crashes, firearm use, and recreational activities.

Assessment and Management Using a light, evaluate the entire eye. Note any blood or discoloration of the sclera. Gentle irrigation usually will not wash out foreign bodies that are stuck to the cornea or lying under the upper eyelid. To examine the undersurface of the upper eyelid, pull the lid upward and forward. If you spot a foreign object on the surface of the eyelid, you may be able to remove it with a moist, sterile, cotton-tipped applicator. Never attempt to remove a foreign body that is stuck or imbedded in the cornea.

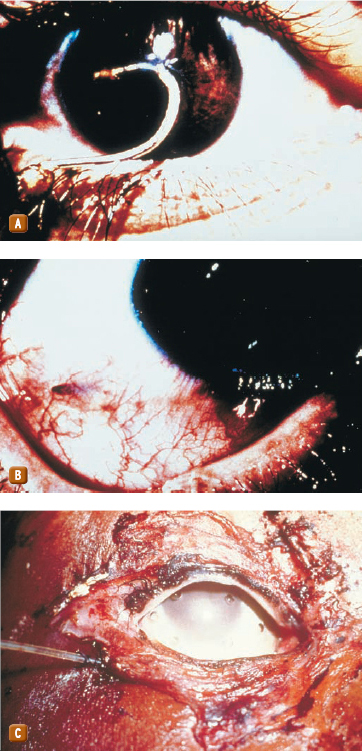

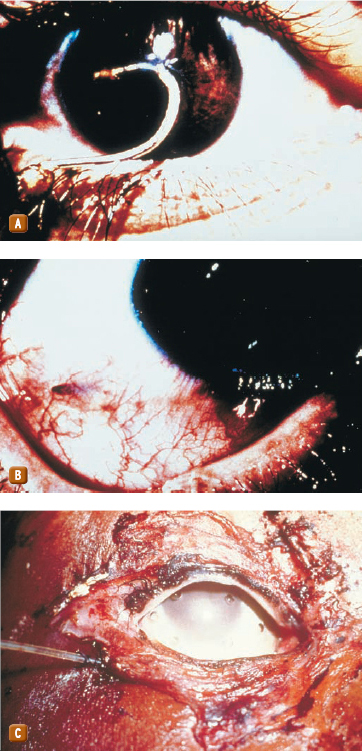

Foreign bodies ranging in size from a pencil to a sliver of metal may be impaled in the eye Figure 8. Clearly, these objects must be removed by a physician.

To ease pain and assist with dislodging the foreign body, begin by irrigating the eye with a sterile saline solution. This will frequently flush away loose, small foreign objects lying on the surface of the eye. Always flush from the nose side of the eye toward the outside to avoid flushing material into the other eye. After its removal, a foreign body will often leave a small abrasion on the surface of the conjunctiva, which leads to continued irritation; for this reason, you should transport the patient to the hospital for further assessment and treatment.

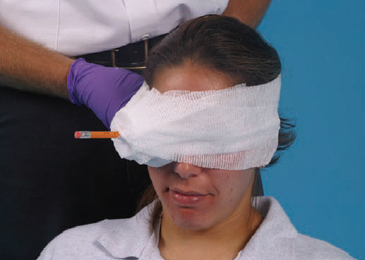

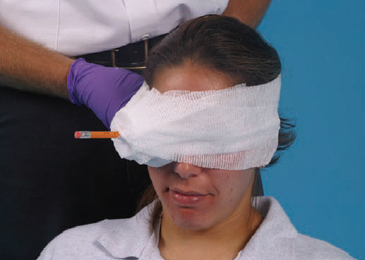

When a foreign body is impaled in the globe, do not remove it! Stabilize it in place. Cover the eye with a moist, sterile dressing; place a cup or other protective barrier over the object, and secure it in place with bulky dressing Figure 9. Cover the unaffected eye to prevent further damage caused by sympathetic eye movement, and promptly transport the patient to the hospital.

Inflammation of the Eyelid (Chalazion and Hordeolum)

The eyelid has oil glands and oil ducts that provide a protective film across the eye. Occasionally these ducts and/or glands become blocked, causing a small swollen bump or pustule on the external eyelid (chalazion) Figure 10. A red tender lump in the eyelid or at the lid margin may be due to a blocked oil duct (hordeolum), commonly known as a stye Figure 11.

Words of Wisdom

Large and small foreign bodies, particularly small metal fragments, can become completely embedded in the globe. The patient may not even be aware of the cause of the problem. Suspect such an injury when the history includes metal work (such as hammering, exposure to splinters, grinders, vigorous filing) and when you observe signs of ocular injury (such as redness, irritation, inflammation).

Figure 8 Any number of objects can be impaled in the eye. A. Fishhook. B. Sharp, metal sliver. C. Knife blade.

Figure 9 Secure an impaled object in the eye with a protective barrier and bulky dressing.

Figure 10 A chalazion is a small, swollen bump or pustule on the external eyelid.

Figure 11 A hordeolum, or stye, is a red, tender lump in the eyelid or at the lid margin.

Assessment and Management The infection that occurs as a result of the clogged ducts is often painful. Infection can progress to become systemic. A thorough assessment of vital signs and history is warranted especially when the patient may now have systemic symptoms.

Paramedics can treat eyelid inflammation with a warm moist washcloth over the affected area, simulating warm soaks that the patient can do at home. The patient should be transported to the emergency department for topical antibiotics and pain management if necessary.

Glaucoma

Glaucoma is a group of conditions that lead to increased intraocular pressure. It is one of the leading causes of blindness. The white fluid in the eye (vitreous humor) circulates nutrients to the lens and part of the cornea. Excess pressure buildup can cause damage to the optic nerve. Glaucoma is usually treated with eye drops to reduce ocular pressures.

Assessment and Management Prehospital complaints may involve the patient reporting a loss of field of vision or a blind spot toward the center of vision. Assessment should rule out any trauma or physical injury to the eye. You will perform a general eye assessment as described earlier, evaluating vision, motility, and any abnormalities of the external eye or anterior surface. Document any pertinent negatives and all abnormal findings. An ophthalmologist will perform a much more comprehensive exam, assessing inner eye pressure, the shape and color of the optic nerve viewed through a dilated pupil, the angle in the eye where the iris meets the cornea, and the thickness of the cornea, and will perform a test to assess the complete field of vision. Because paramedics are not normally trained to do this comprehensive eye exam, all patients with eye injuries or conditions should be taken to the emergency department for follow-up.

Depending on the cause of the pressure buildup, eye drops are usually prescribed to reduce the pressure. Glaucoma increases in incidence with the elderly, but can occur any time from birth forward. Always ask patients which medications they have taken prior to your arrival on the scene. Administration of eye medications in the prehospital setting is usually limited to tetracaine (Pontocaine, Dicaine) for pain relief, or emergency irrigation for removal of a damaging or irritating substance from the eyes. As the population of geriatric patients increases, the scope of practice for the paramedic may change to include limited eye care.

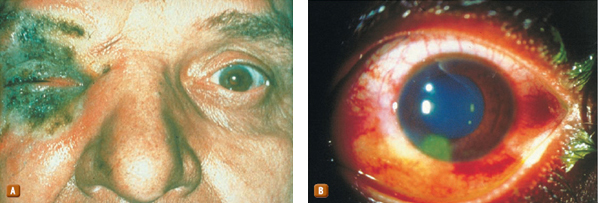

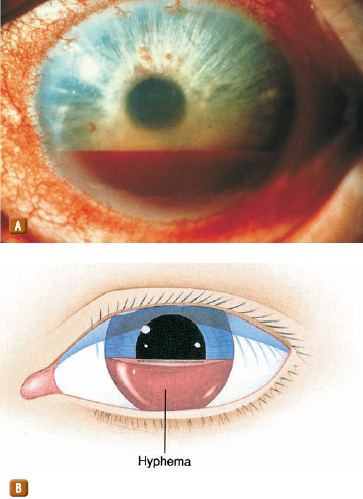

Hyphema

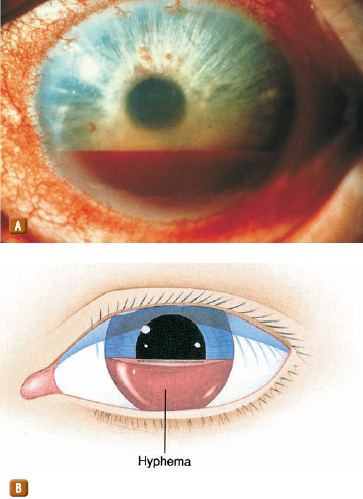

Blunt trauma can cause serious eye injuries, ranging from swelling and ecchymosis Figure 12 to rupture of the globe. Hyphema is bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye that obscures vision, partially or completely Figure 13. It may be the result of blunt trauma to the eye or a medical cause. It may be a marker of damage to other structures of the eye and, therefore, requires a full ophthalmologic examination. One of the concerns is blood clotting in the canal connecting the anterior chamber to the posterior chamber, causing an acute rise in intraocular pressure. Approximately 25% of hyphemas are associated with globe injuries.

Figure 12 Swelling and ecchymosis are hallmark findings associated with blunt trauma to the eye.

Figure 13 A hyphema, characterized by bleeding into the anterior chamber of the eye, can occur following blunt trauma to the eye. This condition should be considered a sight-threatening emergency. A. Actual hyphema. B. Illustration.

Assessment and Management A patient with hyphema is likely to experience pain and possibly blurred vision. The patient will report reduced vision directly proportional to the size of the hyphema. Often the blood is directly visible, but shining a penlight obliquely at the globe may help you to visualize the blood, which will pool with gravity.

If hyphema or rupture of the globe is suspected, take spinal motion restriction precautions. Such injuries indicate that a significant amount of force was applied to the face and, thus, may include a spinal injury. Elevate the head of the backboard approximately 40° to decrease intraocular pressure (IOP) and discourage the patient from performing activities that may increase IOP (eg, coughing).

If there are no other contraindications, transport should be performed with the patient sitting as upright as possible and both eyes should be patched. Pain should be managed with acetaminophen with or without codeine and aspirin; other medications with antiplatelet effects should be avoided. An anxiolytic may facilitate transport.

Iritis

Iritis is inflammation of the iris Figure 14. This is also termed anterior uveitis. Uveitis is the third leading preventable cause of blindness.

Iritis can be acute or chronic. When acute, it can be caused by trauma or irritants, and usually affects only one eye. Autoimmune diseases, different types of arthritis, irritable bowel disease, and Crohn disease can predispose patients to developing iritis. Infectious causes include Lyme disease, tuberculosis, and sexually transmitted diseases.

Assessment and Management Iritis presents as a red area surrounding the iris, cloudy vision, or an unusually shaped pupil. The assessment should focus on history. Many ophthalmologists are not trained to recognize iritis. Patients should be directed to a uveitis specialist or an ocular immunologist.

Acute iritis usually responds well to topical corticosteroids as long as the cause is not fungal, viral, or bacterial. There are over 90 different pathogens or autoimmune processes that have a relationship to chronic or recurrent iritis. These patients should be referred to a specialist. Failure to treat iritis can result in permanent disability.

Figure 14 Iritis is inflammation of the iris.

Papilledema

Papilledema results from swelling or inflammation of the optic nerve at the rear part of the eye. The optic nerve communicates between the eyes and the brain. Patients experience headaches, nausea with possible vomiting, temporary vision loss, or narrowing vision fields. They may also experience a “graying” in their field of vision.

The increased pressure in the brain, which causes optic nerve swelling and inflammation, may have several different causes. Space-occupying lesions like abscesses and tumors can create intracranial pressure increases. An inner ear infection, lung infection, or dental infection can cause pus accumulation in the brain, causing an abscess that presses on the optic nerve. Meningitis, fever, brain tumors, hypertensive crisis, chronic high blood pressure, and other diseases such as Guillain Barré syndrome may all result in an increase in cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) pressures, leading to papilledema.

Assessment and Management The diagnosis of papilledema is made by an ophthalmologist, or emergency department physician, who has been trained to examine the patient’s retina with an ophthalmoscope. If swelling is present, red spots will also indicate bleeding.

Prehospital management consists of treating the symptoms and transporting the patient. As always, assess the ABCs to ensure that there are no life threats. Depending on the severity of anxiousness or pain, the patient may benefit from analgesics or a mild sedative. Vision loss can become permanent if treatment does not begin within a few days of onset; therefore, immediate treatment should be encouraged. Treatment is aimed at the underlying cause of the intracranial pressure increase. Paramedics who have an expanded scope of practice that includes use of an ophthalmoscope should receive further training in the use of this device from their medical director.

Retinal Detachment and Defect

Another potential result of blunt eye trauma is retinal detachment, or separation of the inner layers of the retina from the underlying choroid (the vascular membrane that nourishes the retina). Retinal detachment is often seen in sports injuries, especially boxing.

Assessment and Management This painless condition produces flashing lights, specks, or “floaters” in the field of vision, and a cloud or shade over the patient’s vision. Because it can cause devastating damage to vision, retinal detachment is an ocular emergency and requires immediate medical attention. Transport the patient to the most appropriate emergency department.

Cellulitis of the Orbit: Periorbital and Orbital Cellulitis

Periorbital and orbital cellulitis are both most commonly caused by staphylococcus and streptococcus bacterial infections. The location of these infections determines which type is present.

Periorbital cellulitis is more prevalent in children than adults. Also known as preseptal cellulitis or eyelid cellulitis, it presents as a painful, red, swollen eyelid. Fever may also be a symptom along with redness of the white part of the eyes (conjunctivitis). Insect bites, upper respiratory disorders, and trauma increase the potential to develop periorbital cellulitis.

Orbital cellulitis is an infection within the eye socket and is considered a medical emergency because it can lead to permanent vision problems and blindness. The goal of treatment is to avoid the formation of an abscess. Predisposed risk factors include sinusitis, tooth infections, facial or middle ear infections, trauma, and sinus infections.

Assessment and Management Treatment in children is usually IV antibiotics for both forms of cellulitis. Adults are treated with oral antibiotics; however, if symptoms are severe, IV antibiotics are used for adults as well.

Prehospital management is directed at ruling out life threats with a thorough history and transporting the patient to the appropriate care.

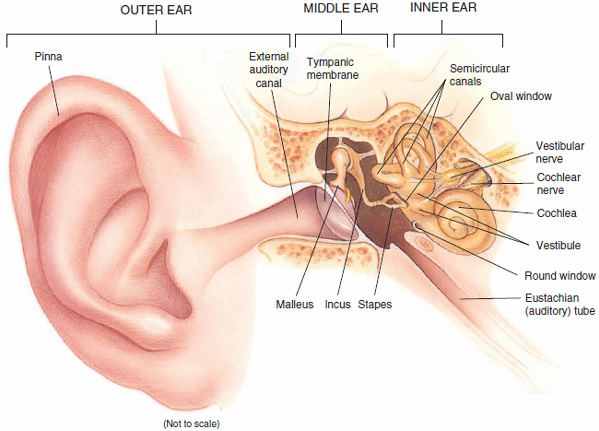

The Ear

The Ear

The ear is the primary structure for hearing and balance, but is also integral to self-protection. When you think of ear problems, you most likely think of hearing loss. But hearing is not all the ear affects; the ear also plays in important part in balance and orientation. Disorders and injury to the ear can leave a person unable to communicate, react, and maintain equilibrium. For example, scuba divers are susceptible to vertigo from cold water moving into the ear canal during pressure equalization. A tumor that grows on the eighth cranial nerve (acoustic neuroma) can affect the inner ear and balance. The tumor is usually slow growing, but if it grows larger, other cranial nerves can be affected, including the fifth, sixth, and seventh. This can affect facial sensation, eye movement, facial movement, taste, and hearing.

Loss of hearing is a large health problem for adults, most likely associated with occupational noise injury. Hearing loss can affect a child’s ability to develop communication, language, and social skills. The earlier children with hearing loss start receiving services, the more likely they are to reach their full potential.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Ear

Anatomy and Physiology of the Ear

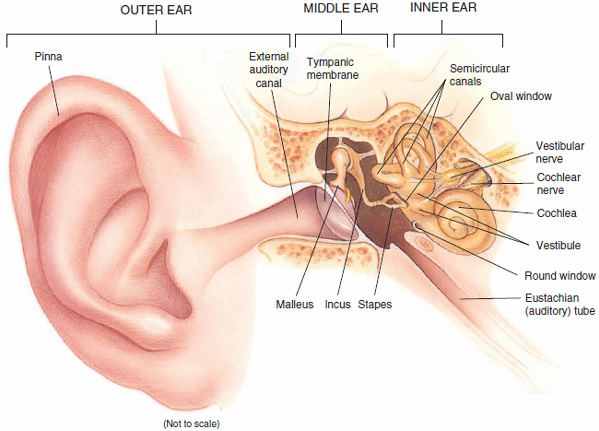

The ear is divided into three anatomic parts: external, middle, and inner Figure 15. The external ear consists of the pinna, external auditory canal, and the exterior portion of the tympanic membrane or what is commonly known as the eardrum. The middle ear consists of the inner portion of the tympanic membrane and the ossicles while the inner ear consists of the cochlea and semicircular canals.

Sound waves enter the ear through the auricle, or pinna, the large cartilaginous external portion of the ear. They then travel through the external auditory canal to the tympanic membrane. Vibration of sound waves against the tympanic membrane sets up vibration in the ossicles, the three small bones on the inner side of the tympanic membrane. These vibrations are transmitted to the cochlear duct at the oval window, the opening between the middle ear and the vestibule. Movement of the oval window causes fluid within the cochlea, a shell-shaped structure in the inner ear, to vibrate. Within the cochlea at the organ of Corti, vibration stimulates hair movements that form nerve impulses that travel to the brain via the auditory nerve. The brain then converts these impulses into sound.

Special Populations

Hearing loss is more common in the older population than vision loss. With age, changes in the structures of hearing result in loss of high-frequency hearing, or even deafness. If an older patient uses a hearing aid for everyday activity, it is best to keep it in place to provide for better communication during transport to the hospital.

Consider learning American Sign Language so that you can better communicate with patients who are deaf.

Patient Assessment

Patient Assessment

Initial observation of the scene must rule out hazards to EMS personnel and crew. Blast injuries warrant special consideration as to approach, staging, and scene safety; these are discussed in the chapter, Trauma Systems and Mechanism of Injury.

Foreign objects forced into the auditory canal can damage the eardrum. Ear infections may cause the eardrum to blister and bleed. Inner ear infections can cause excessive pressures behind the eardrum. Blast pressure waves can burst the eardrum. When altitudes are rapidly changing, equalizing pressures can be difficult if the eustachian tubes are clogged from a cold, allergy, or inflammation. When a person moves to a higher altitude, expanding air needs to be released from the inner ear. Swallowing and plugging the nose and blowing against a closed glottis can relieve the pressure.

As you approach the patient, aside from determining the approximate age, sex, environmental conditions, and degree of distress, note whether the patient has a hearing aid. Sometimes patients do not sleep with their hearing aid in and they may seem confused until you are told by someone else that the patient cannot hear you!

Assessment and management of the patient with an ear condition begins by ensuring airway patency, breathing adequacy, circulation, and managing any threats to life. Although patients with ear conditions may be in pain or have a hearing deficit, they generally are not considered the highest priority nor have a life threat that needs to be immediately dealt with.

Typically, medical conditions involving the ears are not life threats unless they are a symptom of a much more serious problem (eg, ear damage from a blast injury or head trauma).

Figure 15 The structures of the ear.

These patients may be very uncomfortable and their condition cannot be resolved in the field. Therefore, transport these patients to the emergency department where they can receive the appropriate physical examination, diagnosis, and treatment.

Take a complete history and find out if the patient has had this condition before. Observe the ears for drainage, excess cerumen, and inflammation or swelling. If the patient has pain, it should be quantified on a pain scale and identified by region and cause. When asking OPQRST assessment questions, P, provocation, should include pertinent negatives, such as “Does it hurt when you swallow, sneeze, cough, or when you bend over?” History of the events leading up to the complaint can help provide clues to the onset of symptoms. The patient may describe unusual pressure changes with “ear popping,” itching in the ears, a recent respiratory infection or cold, or a scuba diving trip. Paramedics generally will treat only the discomfort caused by the symptoms and will pass on the history to the treating facility.

Assess for new aberrations in hearing perception. If hearing is affected, changes should be noted and reassessed during transport. Ask the patient if he or she has experienced tinnitus (ringing in the ears) or dizziness. Inspect and palpate for wounds, swelling, or drainage (pus, blood, cerebrospinal fluid). Often the mastoid process of the skull, which is palpated immediately posterior to the auricle, is assessed for discoloration and tenderness (Battle sign). Abnormalities of the external canal and tympanic membrane are visualized by use of an otoscope. This skill is shown in the chapter, Patient Assessment. Trauma to the ears is discussed in the chapter, Face and Neck Trauma.

An adequate assessment of the external ear canal and middle ear cannot be performed in the field. Transport the patient, and as always, be sure to document your findings and communicate as appropriate with the receiving facility.

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Ear Injuries

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Ear Injuries

Foreign Body

Foreign bodies in the ear are most likely to be seen in the pediatric population. The majority of the objects are solid, such as beads, stones, or even erasers. However, it is possible for an insect to crawl into the ear canal or for a child to put vegetative matter in the ear.

Assessment and Management Assessment of the foreign body should determine the nature of the object and the urgency of treatment. The assessment of a foreign body in the ear in the prehospital environment is limited to visual clues if the object can be seen. Look for bleeding, redness or inflammation, and symptoms associated with infection. Some objects such as organic matter and food will swell from moisture and may become more entrapped as they swell. Small batteries such as those found in watches can leak chemicals and cause burns if left untreated. Serious symptoms or discomfort, as well as inserted objects that may cause harm or damage if left untreated, must be considered an emergency.

The ear canal is narrow and angulated. Probing for foreign bodies in the ear is discouraged. In some areas the paramedic may use an otoscope to look further into the ear; however, that is outside the scope of practice in most regions.

As is the case with almost all foreign bodies, observe and document, but do not pull the impaled object out. Rather, simply stabilize it in place. The pediatric ear canal is small and any effort to retrieve the foreign object may do more harm.

Due to the potential for infection and damage to the ear drum, these patients should be seen by a physician in the ED. Management of both adults and children is to transport to the appropriate facility in the position of comfort. Severe pain or anxiousness can be treated with pain management medication and/or mild sedation.

Impacted Cerumen

Cerumen is the yellowish oily substance found in the outer ear canal. It helps prevent dirt and water from entering the middle ear canal and may protect the ear from bacteria or fungus. Cerumen may present as “wet,” which is a sticky brown color, or “dry” as a greyish flaky substance. Commonly known as “earwax,” cerumen can become impacted and cause pressure against the eardrum. Impaction occurs when too much cerumen builds up and gets stuck in the outer ear canal.

Normally cerumen flows outwardly toward the outer ear and gets washed away. It helps remove dead skin cells from the ear canal. Cerumen impaction is more common in the elderly, where hearing aids may block the normal flow. The elderly also tend to produce cerumen that is dry and thus is more prone to buildup. Men and people with mental behavior disorders are more likely to develop impacted cerumen. Other risk factors include abnormal ear canal shape and diseases that cause more production of cerumen, such as keratosis. Improper use of cotton swabs and other hygiene tools or objects can block the flow and cause a cerumen plug.

Assessment and Management Symptoms include sensation of pressure or fullness in the ear, dizziness, ringing in the ears, loss of hearing, and pain or itching in the ear. Prehospital treatment should include a thorough history and visual inspection of the ear canal. Because an elderly person may have many different medical conditions, it may be difficult to rule out other serious problems. It may be likely that elderly patients with impacted cerumen may not have seen a physician lately for various socioeconomic reasons.

Treatment is aimed at removing the excess cerumen. An otoscope will be used by a physician to identify the problem. Once found, irrigation or tools designed to remove the wax will be used. Suction and eardrops such as wax softeners may also be used. Untreated, cerumen can cause infection and irritation that can potentially damage the eardrum and hearing. The process of removing cerumen may also cause injury, so follow-up is necessary after the procedure.

Labyrinthitis

Labyrinthitis is most recognized as the feeling of vertigo or loss of balance after an ear infection or upper respiratory infection. Irritation and swelling in the inner ear affects the nerves of the inner ear and produces a loss of balance. Other symptoms include ringing in the ears (tinnitus), dizziness, loss of hearing, nausea, and vomiting. Permanent hearing loss can occur.

YOU are the Medic PART 3

You ask, “Jimmy, are you having a hard time swallowing?” Instead of answering, Jimmy slowly nods his head. You ask him if he can talk to you. When Jimmy tries, he ends up coughing. It sounds high pitched and painful. Jimmy looks like he is working hard to breathe. The administrator says she was able to contact Jimmy’s mom and that she will meet you at Parkside Hospital.

Recording Time: 3 Minutes |

|

Respirations |

20 breaths/min |

Pulse |

120 beats/min |

Skin |

Hot, pale, moist |

Blood pressure |

106/82 mm Hg |

Oxygen saturation (SpO2) |

97% room air |

Pupils |

Equal and reactive |

5. What do you suspect is wrong with the patient?

6. Do you have any additional concerns because this child appears drowsy but is working hard to breathe?

Assessment and Management Severe symptoms usually resolve within a week. Prehospital treatment is directed at reducing the severity of the nausea and vomiting and transporting the patient in a position of comfort. The differential diagnoses for vertigo with associated nausea include neurologic disorders such as Meniere disease and acoustic neuroma. These serious disorders will need to be ruled out by a CT scan and an MRI. You should be able to recognize the serious implications of the symptoms and suggest the patient be seen at the emergency department.

Hospital treatment of labyrinthitis includes an antiemetic for nausea and vomiting, an antihistamine to reduce swelling, anti-vertigo medicine, and diazepam (Valium) as a sedative/muscle relaxant. Prompt treatment of respiratory and ear infections reduces the risk of labyrinthitis.

Meniere Disease

Meniere disease is an inner ear disorder, usually affecting adults (mostly those older than 50 years), in which endolymphatic rupture creates increased pressure in the cochlear duct, which then leads to damage to the organ of Corti and the semicircular canal. Meniere disease may have an abrupt onset. Dilation of the endolymphatic spaces occurs after rupture and healing. Hypersecretion or underabsorption occurs, which results in excess fluid in the endolymphatic space. Patients will likely experience severe vertigo (dizziness), tinnitus (perception of sound in the inner ear with no external environmental cause), and sensorineuronal hearing loss.

Assessment and Management Assessment of a patient with Meniere disease is not likely to be performed in the field. The symptoms of hearing loss, ear pressure, vertigo, dizziness, nausea, and vomiting have a number of causes, including viral, bacterial, and neurologic causes, among others. In the prehospital setting, care is focused on treating the nausea and vomiting with an antiemetic. In the clinical setting, after diagnosis, the physician may treat the fluid buildup with diuretics and the nausea with an antiemetic (Compazine). There are surgical procedures that have had limited success. In most patients, Meniere disease resolves very gradually over 2 to 8 years.

Otitis Externa and Media

Otitis is an infection that results from bacterial growth in the ear canal. It can be categorized into otitis externa and otitis media. These are infections of the outer and middle ear cavity, respectively. This is more common in children than in adults partially because as humans grow, the angle of the tube becomes more vertical, allowing the tubes to drain more easily. The angle of the eustachian tube in some children is almost horizontal, preventing the tube from properly draining and allowing infective material to collect. In children younger than 5 years, otitis media is the most common affliction requiring medical intervention.

Otitis externa and otitis media are most commonly bacterial infections, but otitis externa can also be an allergic or fungal reaction and otitis media can be virally induced, developing when sinusitis or rhinitis spreads along the eustachian tubes. Also, auditory canal blockage from excessive cerumen or lack of enough cerumen can lead to bacterial growth that can cause infection.

Assessment and Management

Both otitis externa and media are painful conditions. Allergic or fungal otitis externa may be accompanied by itching, and examination of the external ear canal will show edema and erythema. Patients with otitis media may experience diminished hearing acuity, and examination with an otoscope will reveal an inflamed, bulging tympanic membrane (eardrum). The otoscope is a device designed to look in a patient’s ears Figure 16. Use of this device is covered in the chapter, Patient Assessment. Typically paramedics do not use these devices unless they work in an expanded scope of practice in which they have received additional training from their medical director. Both disorders are common in children and prior to language development, children will often indicate ear pain by pulling at or rubbing the infected ear. In severe cases the tympanic membrane may tear or rupture, revealing blood in the external ear canal. Untreated infections can cause permanent hearing loss.

Prehospital treatment should be directed at relieving unbearable symptoms. The physician will treat the patient with topical antibiotics and possibly corticosteroids to reduce inflammation. The paramedic should monitor the patient’s condition and administer pain medication when necessary. In the hospital setting, if the symptoms are tolerated, the patient’s condition is monitored. If no improvement occurs, antibiotics are administered. When the physician can see a bulging tympanic membrane from excess fluid buildup in the middle ear, additional antibiotics may be administered. When several trials of antibiotics have been unsuccessful, such as in children who have immune deficiencies, tympanocentesis (needle aspiration) is performed by a physician. The middle ear fluid that has been aspirated is cultured. This aids in specific treatment for the bacteria present. The results of the culture will indicate the type of bacteria present and aid in determining the treatment necessary.

Figure 16 An otoscope.

Perforated Tympanic Membrane

Perforation of the tympanic membrane (ruptured eardrum) can result from foreign bodies in the ear or from pressure-related injuries, such as blast injuries resulting from an explosion, or diving-related injuries that result in barotrauma to the ear. Blast injuries are covered in more detail in the chapter, Terrorism. Diving injuries are covered in the chapter, Environmental Emergencies.

Assessment and Management Signs and symptoms of a perforated tympanic membrane include loss of hearing and blood drainage from the ear. Although the injury is extremely painful for the patient, the tympanic membrane typically heals spontaneously and without complication. Nevertheless, a careful assessment should be performed to detect and treat other injuries, some of which may be life threatening. Transport the patient for further evaluation. Pain management should be considered in severe cases.

The Nose

The Nose

The nose is subject to increased rates of injury because of its prominent location on the human face. Your nose is a filter, humidifier, and heater for the air that enters the body. Allergens, particles, and chemicals can cause inflammation, infection, and injury. Because the sinus cavities are in the forehead and face, and drain to the back of the throat, complications from nasal disorders are common. Sinus headaches from pressure, scratchy throat from drainage, and respiratory infection from the aspiration of draining, infected material all lead to other manifestations and systemic infections. You may encounter a myriad of symptoms that may have begun as a nasal infection.

The inside of the nose is extremely vascular. Although this can cause it to bleed, this also makes intranasal medication administration an excellent route for some medicines. It is also a common route for drug abuse such as cocaine. The nasal mucosa is also a short route to the brain. The blood-brain barrier can be bypassed through the nasal mucosa by entering the spinal fluid. This makes the intranasal route faster than intravenous administration with some medicines.

As any person knows, another main function of the nose is the ability to smell. Loss of smelling sensation has many different causes, including aging, smoking, allergies, rhinitis, polyps, the flu, medications, and traumatic brain injury (damage to cranial nerve 1 [the olfactory nerve]). Different types of smelling disorders include anosmia (total loss of sense of smell), dysosmia (distorted sense of smell in which the person perceives unpleasant odors when the odors do not exist), hyperosmia (increased sensitivity to smell), hyposmia (decreased sense of smell), and presbyosmia (loss of smell from normal aging). Loss of smell also affects a person’s sense of taste.

Anatomy and Physiology of the Nose

Anatomy and Physiology of the Nose

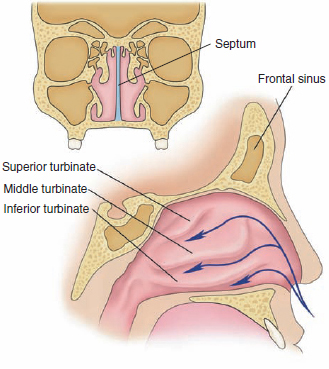

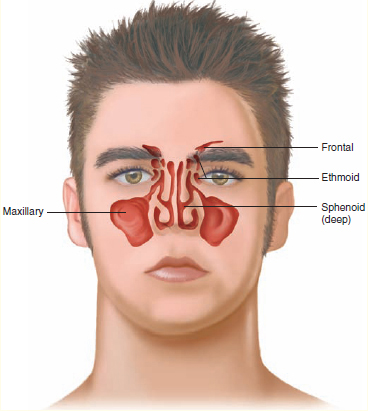

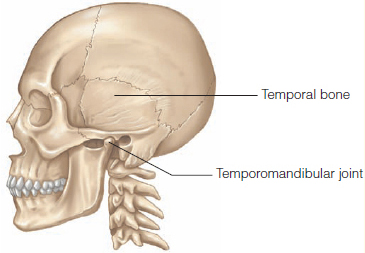

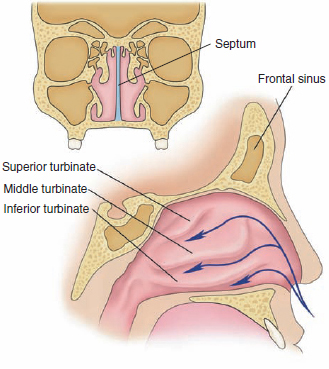

The nose is one of the two primary entry points for oxygen-rich air to enter the body. The nasal septum—the separation between the nostrils—is located in the midline Figure 17. Often, it bulges slightly to one side or the other. The external portion of the nose is formed mostly of cartilage.

Within each nasal chamber are layers of bone called the turbinates, which are covered with a moist lining. Both chambers have a superior turbinate, a middle turbinate, and an inferior turbinate. As a person breathes, air moves through the nasal chambers and is humidified as it passes over the turbinates. Directly above the nose are the frontal sinuses and, on either side, the orbit of the eye.

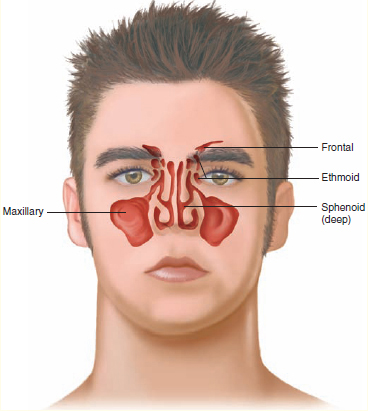

Several bones associated with the nose contain cavities known as the paranasal sinuses Figure 18. These hollowed sections of bone, which are lined with mucous membranes, decrease the weight of the skull and provide resonance for the voice. The contents of the sinuses drain into the nasal cavity.

Patient Assessment

Patient Assessment

An ambulance summoned for a complaint of the nose could have several etiologies. The condition of the residence as you approach can give clues to exposure. A factory spewing toxins, the scent of cleaning agents in the hallway, or other unpleasant odors can alert the paramedic to possible dangers to the crew. Until the seriousness of the problem is known, standard precautions are key to limiting the spread of respiratory infections.

Figure 17 The nose has two chambers, divided by the septum. Each chamber is composed of layers of bone called turbinates. Above the nose are the frontal sinuses and, on either side, the orbit of the eye.

Figure 18 The paranasal sinuses

When the scene is determined to be safe for the crew to respond, the first impression of the patient can tell you if airway and breathing are sufficient, and you can note the amount of distress your patient is experiencing. Environmental clues, as well as your own nose, can identify possible irritants. Remember, a sneezing, sniffling, coughing patient easily spreads airborne germs in water droplets.

The vascular nature of the nasal cavities make them susceptible to bleeding. A severe nosebleed or condition that blocks the airway with swelling or blood is a life-threatening condition. You must be able to determine whether the patient has a general medical condition or if the condition is or could become life threatening.

Insert an airway adjunct as needed to maintain airway patency. However, do not insert a nasopharyngeal airway or attempt nasotracheal intubation in any patient with suspected nasal fractures or in patients with CSF or blood leakage from the nose. After establishing and maintaining a patent airway, assess the patient’s breathing and intervene appropriately.

Inquire about a previous history of nose conditions or bleeding that needed to be packed and quartered in the emergency department. Always consider hypertensive crisis when an elderly person has a nosebleed.

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Specific Conditions

Pathophysiology, Assessment, and Management of Specific Conditions

Epistaxis

Epistaxis, or nosebleed, is a common problem that can occur spontaneously or from trauma. One of the most common causes of nosebleeds is digital trauma (picking the nose with a finger); other causes include dryness and hypertension. Nosebleeds are further classified into anterior and posterior epistaxis. Anterior nosebleeds usually originate from the area of the septum and bleed fairly slowly. These are usually self-limiting and resolve quickly. Posterior nosebleeds are usually more severe and often cause blood to drain into the patient’s throat, causing nausea and vomiting.

Words of Wisdom

Blood or CSF drainage from the nose (cerebrospinal rhinorrhea) suggests a skull fracture. Do not make any attempt to control this bleeding; doing so may increase intracranial pressure (ICP) if the patient has a concomitant brain injury. Furthermore, the insertion of nasal airway adjuncts and nasotracheal intubation should be avoided in patients with suspected nasal fractures, especially if rhinorrhea is present. A nasally inserted airway device could enter the cranial vault through an occult fracture (such as a cribriform plate fracture) and penetrate the brain, further worsening the situation.

Assessment and Management For a nontrauma patient who is bleeding from the nose, you should place the patient in a sitting position, leaning forward, and pinch his or her nostrils together Figure 19. Direct the patient not to sniffle or blow his or her nose. For a detailed discussion of the care for epistaxis in the context of trauma, see the chapter, Bleeding.

Foreign Body

Foreign bodies in the nose are most likely to be seen in the pediatric population and are commonly solid objects, such as beads, stones, marbles, or small pieces of food. Children age 2 to 5 years have the greatest incidence of exploring their nasal cavities with foreign objects. At age 9 months, a child’s grip is sufficient to grasp an object and direct it up one or both nares. Food, toys, rocks, and beads may become lodged or travel to the mouth through the nasal pharyngeal cavity. Those objects that make it to the mouth become a risk for inhalation or may become lodged in the esophagus if swallowed. Objects lodged in place can cause other complications. Pressure in the delicate nasal passage can cause tissue necrosis, inflammation, and swelling. The inflammatory process can cause tissue ulceration and epistaxis. Nasal blockage can lead to sinusitis. Rhinotillexomania (nose picking) in adults is a cause of nasal infections and the introduction of irritants to the nasal mucosa. (There is even limited evidence that spontaneous epistaxis from nose picking has led to motor vehicular crashes!)

Figure 19 Control bleeding from the nose by pinching the nostrils together.

Assessment and Management In all patients, the paramedic must determine if the foreign body presents a life-threatening condition. Nasal foreign bodies are usually visible in the anterior nares, but some may be far enough into the nares as to not be seen on visual examination. If you do see the object, you may only see one end of the object; the other end may be lodged in place. Any persistent, foul-smelling, purulent discharge from the nares should lead to suspicion of a foreign body. If you note a discharge from the nose, let it drain, treat it as potentially infective material, and transport the patient. Remember to always use standard precautions.

Any lodged object should be removed in the hospital after radiography. Transport the patient in the position of comfort with an emphasis on limiting the ability of gravity to introduce the object further into the cavity. Preventing aspiration is a priority. Where the object is an extreme irritant, pain management may be necessary. Sedation may be necessary in rare cases. Consultation with medical control is advised.

Rhinitis

Rhinitis is a nasal disorder that is most common during childhood and adolescence. There are many causes of this common complaint. It is generally caused by allergens (pollen, dust, house mites, animal dander). Once inhaled, the body’s store of immunoglobulin E (IgE) binds to the allergens, which then produce chemicals that can cause inflammation. Rhinitis can also be caused by viruses, certain medications (high blood pressure medications), low humidity, cold temperatures, foreign bodies, irritants in the air (smoke, chemicals), the “common cold” (nasal infection), and hormonal changes in pregnancy.

Assessment and Management Signs and symptoms of rhinitis include nasal congestion, sneezing, itchy runny nose, itchy eyes, postnasal drip (which may feel like a tickle in the throat), and possibly cough. Because there is little you can perform in the way of treatment, keep the patient in a Fowler position and provide transport. Physician-directed treatment is aimed at treating the cause of the rhinitis.

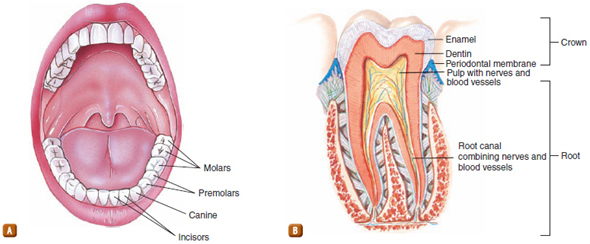

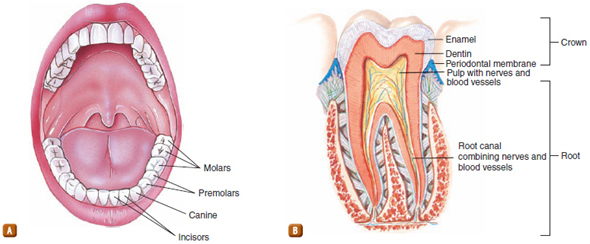

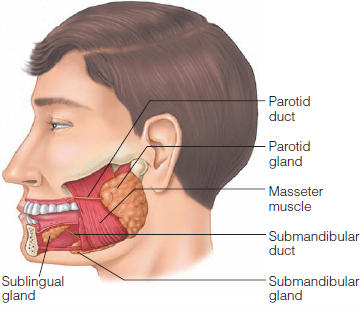

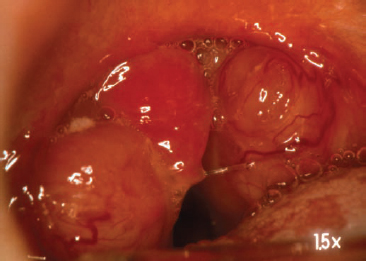

Sinusitis