THE DEFUNCT FRANCHISES

★ ★ ★

Teams never die — they just leave their home cities once in a while. It might sound somewhat cliché to say this, but it’s true — long after a franchise departs from the NHL, you’ll still see the indelible mark it made on a market and its fans. Years after a departure, the evidence is still there in the jerseys that fans wear to games or the photos they prefer to gather in their collections.

Though early clubs like the Philadelphia Quakers or Hamilton Tigers are all but forgotten franchises, the post-expansion era has seen a multitude of teams come and go. Among these are two of the Expansion Six clubs (the Minnesota North Stars and Oakland Seals), a few from the 1970s (the Atlanta Flames, Kansas City Scouts, Cleveland Barons, and Colorado Rockies), three WHA imports (the Winnipeg Jets, Hartford Whalers, and Quebec Nordiques), and even a more modern squad (the Atlanta Thrashers), and this is just in the National Hockey League — I could be sitting for days listing off expired WHA, AHL, and CHL franchises from years gone by.

These historic teams, the vast majority of whose players and fans have passed on — taking with them the connections to those former clubs — are well remembered. Witness fans’ tie to the Montreal Maroons, Quebec Bulldogs, or original Ottawa Senators for evidence. Thus, it’s important to remember these teams — and the multitude of memorabilia generated for former franchises — including five standout organizations that, though long departed, are still very much remembered by the NHL’s faithful.

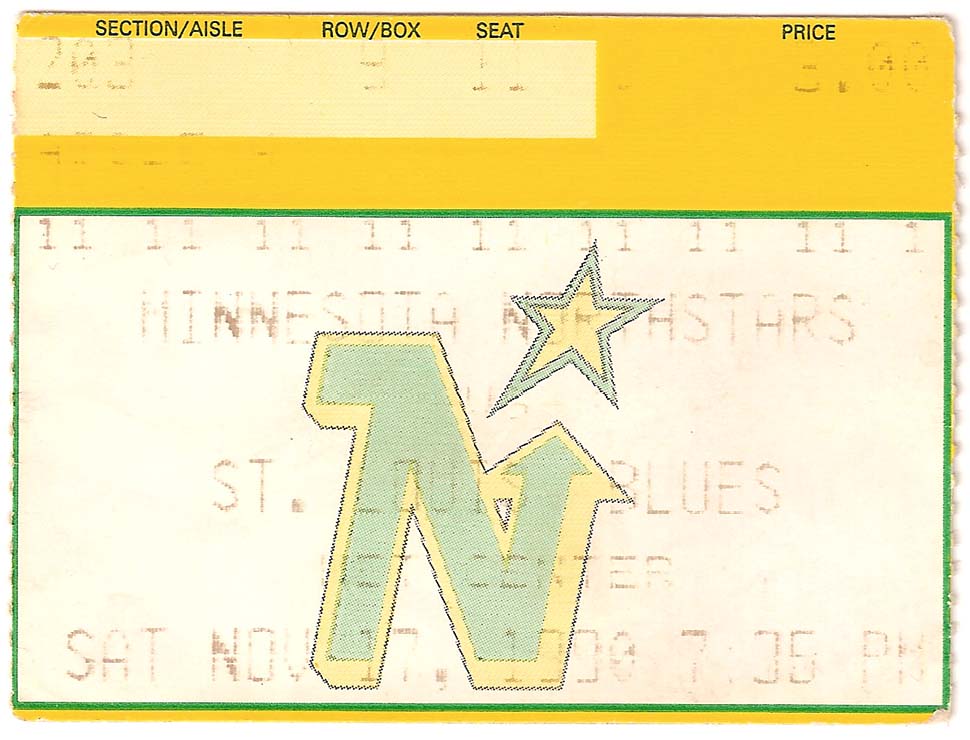

MINNESOTA NORTH STARS

One of the Expansion Six, the North Stars filled a pretty obvious void on the NHL’s map — the heartland of U.S. hockey. Over the course of 26 years in the NHL, the North Stars volleyed between being Cup contenders and one of the poorest-performing teams in the league. They came within one game of going to the Stanley Cup Finals in their first year but struggled to regain that magic in subsequent years.

JON WALDMAN

Through the 1970s, the North Stars were without a true superstar; they were a lunchbox-style squad, with names like JP Parise, Danny Grant, and Jude Drouin being part of the club. Once the squad merged with the Cleveland Barons and drafted Bobby Smith in 1978, the team started to make a turnaround. Subsequent drafts brought the likes of Dino Ciccarelli and Neal Broten on board, helping solidify a roster that made it to the championship round in 1981 against the New York Islanders (the less said about that series, the better).

Undeterred, the North Stars continued to put together a solid lineup, adding Brian Bellows and trading for Keith Acton and Mark Napier; but the wheels began to fall off slowly, to the point that the club ended the 1987–88 season the worst in the NHL. The blessing in disguise here was the selection of Mike Modano, arguably the most beloved player in North Stars history. With Modano at the helm of the club and Jon Casey in net, the team became a Cinderella story in 1991, reaching the Stanley Cup Finals. The clock struck midnight a little too early, however, and they fell to the Pittsburgh Penguins.

Soon after that series in 1991 ended, the fate of the Minnesota team changed forever. That summer, the North Stars were essentially split in two. The Gund family, who had previously owned the Barons, separated from the franchise and took with them a number of players to their new team — the San Jose Sharks — via a Dispersal Draft. One year prior, arrangements had been made for a group to buy the North Stars franchise, and the ultimate controlling owner turned out to be Norm Green. Green, just a couple short years later, sealed the North Stars’ fate, relocating the team to Dallas.

With Modano having retired in 2010–11, the North Stars lost their final active alumn. Now all that remains for the small-market franchise is commemorative memorabilia, including an excellent book entitled Minnesota North Stars: History and Memories with Lou Nanne, produced by the hard work of author Bob Flowers and, of course, the former player–coach–general manager (and yes, for a time Nanne held all three positions at once).

QUEBEC NORDIQUES

One can argue that throughout the 1980s there was no greater feud in hockey than the Battle of Quebec. While the Calgary Flames and Edmonton Oilers had highly spirited standoffs on the western front, the pure and unadulterated hatred that Montreal Canadiens and Quebec Nordiques fans had for each other was a whole other level of competitiveness, most vividly seen in the famed “Good Friday Massacre.” During the April 20, 1984, playoff contest, competition between the two clubs got vicious. After earlier fights, the two teams cleared their benches, twice, for all-out brawls on the frozen floor of the Montreal Forum (amid the action, Jean Hamel was knocked out cold). A total of 10 ejections took place during that game, which eventually saw the Habs win the contest and playoff series.

JON WALDMAN

The fight was emblematic of the Nords’ NHL tenure. They were certainly talented enough to make noise in the league, featuring the likes of Hall of Famers Michel Goulet and Peter Stastny; but there was something that never quite clicked with the club. Granted, they were playing in an era dominated by the New York Islanders and western Canadian teams, but they just could not get the puck to go their way. As one of the four refugee WHA teams picked up and stripped by the NHL, the Nords brought with them a fierce competitiveness to the league, and up until the late 1980s the team fared well on the ice. But the wheels began to fall off toward the end of the decade. For three straight years, the club drafted first overall in the NHL Entry Draft thanks to their poor play. The result was Mats Sundin and Owen Nolan suiting up for the franchise, and one of the most famous trades in hockey history as the 1991 selection, Eric Lindros, was shipped to Philadelphia for Peter Forsberg, Ron Hextall, and a vast number of other players and picks.

That trade, of course, ended up being very instrumental in the success of the franchise’s 1996 Stanley Cup run, but by that time the Nords had left for Colorado. Amid the 1994–95 lockout-shortened season, the Nords were in deep financial trouble due to the ever-dangerous elixir of being a small-market franchise in a league with escalating salaries. Mix in the descent of the Canadian dollar and the refusal by government for bailout money, and the death knell rang for the franchise.

Currently, there is a renewed optimism about bringing the NHL back to the French Canadian capital. Talk of a new arena, supported heavily by the provincial government, rules the day, while former Nords’ faithful make an annual sojourn to New York to see the Islanders play. It is believed by some that the franchise will end up moving to Quebec when the new facility is ready. Until then, hockey fans have been blessed with a number of souvenirs of Les Nordiques, with retro products, like figurines of Joe Sakic, abounding.

HARTFORD WHALERS

As much as the Whalers were known during their WHA and NHL tenures as a team that had great resiliency and a drive to succeed, their civic government proved even tougher after the team relocated. You see, as the memorabilia craze picked up in the early 2000s and retro team pieces, primarily jerseys, became the most in-demand souvenirs, Whalers items were nowhere to be found. If you wanted a puck emblazoned with the famed W-and-fishtail logo to be signed by Gordie Howe or Ron Francis, you had to scour for an original. The reason for this? For years, the state of Connecticut owned the rights to the logo and seemingly wouldn’t release it. It took the expiry of the ownership rights to the insignia for a rush of memorabilia to surface, most notably those jerseys.

GEOFF INDER

Tribute artifacts were scarce for the Whalers up until very recent years, but the memory of the franchise never died. Originally a WHA franchise located in Boston (though known as the New England Whalers throughout their time in the rebel league), the team is historically best known for being the first team to win the Avco Cup and to house Gord, Mark, and Marty Howe. The only non-Canadian team to join the NHL, the Whalers did so as a definite cause célèbre, with two of the league’s all-time greats — Howe and Dave Keon — on their roster. Bobby Hull joined the team later on in that season.

After that first season, the Whalers still had tremendous fanfare with the likes of Ron Francis, Kevin Dineen, and Mike Liut cycling through the team but struggled against Adams Division rivals the Montreal Canadiens and Boston Bruins; and when they weren’t suffering from their own bad play, they were suffering from bad trades, such as the infamous 1991 blockbuster swap that saw Francis, Ulf Samuelsson, and Grant Jennings leave for Pittsburgh in exchange for John Cullen, Zarley Zalapski, and Jeff Parker. The result? Two Cups for Francis and Co., none for Hartford.

Even with emerging stars like Geoff Sanderson, Chris Pronger, and Bobby Holik, the Whalers saw their last playoff series in 1992. Other stars and future phenoms spent time in Hartford, but none were able to get the Whalers to the promised land. As season ticket purchases dwindled, talk of relocation began, and in 1997, Peter Karmanos moved the team to Carolina. Though the new Hurricane franchise also struggled at the box office to start, they were ultimately successful on the ice, winning the Stanley Cup in 2006.

WINNIPEG JETS

“It was great to start my career where hockey was such a big deal.”

This quote came from NHL legend Teemu Selanne back in 2003; but it could very well have come from any number of NHLers who got their first taste of hockey action skating at the Winnipeg Arena. Look up and down the roster of the original squad, and you’ll see a number of notable names who first plied their trade professionally in North America. Dale Hawerchuk, Keith Tkachuk, Nikolai Khabibulin, Kris Draper, and several others are among these men.

The Jets franchise was more than just a breeding ground for future superstars with other franchises. While the team did not enjoy the kind of success it had in the WHA, where it won three Avco championships, it was a team that had flashes of brilliance. Had it not been for powerhouse franchises in Edmonton and Calgary, the Jets’ golden years in the mid-1980s may have led to Stanley Cup success.

JON WALDMAN

Ultimately, the Jets faced similar problems to its WHA cousin, the Quebec Nordiques. Financial woes of playing in a small Canadian market and an aging building were ultimately the downfall of the team, whose fans rallied multiple times to save their beloved Jets. Most famously, during the 1994–95 season, everyone from business execs to school children pooled whatever money they could to save their franchise. The result of this devotion, even after a tribute “funeral” where Thomas Steen’s jersey number was retired, was a stay of execution, allowing one final season of NHL hockey in Winnipeg.

That final year was a memorable one indeed. Dubbed “A Season to Remember” — a slogan that appeared on patches on the team jerseys — the Jets played their hearts out and made one last trip to the Stanley Cup playoffs before being dispatched by the Detroit Red Wings and becoming the Phoenix Coyotes.

NEW YORK AMERICANS

What, you were expecting to see another story from the NHL’s modern era? Sure, I could’ve thrown in an entry about the Colorado Rockies or either of Atlanta’s two failed hockey teams, but when you compare these or other franchises to the uniqueness of the Americans, there is little doubt as to which team is more fondly remembered.

HERITAGE AUCTIONS

Born in an era when the NHL was in its infancy, the Americans were a unique group, almost akin to baseball’s Brooklyn Dodgers. The team struggled at the gate, especially in comparison to the rival New York Rangers, who battled with their cousins for the right to play in the famed Madison Square Garden. Originally, the Americans (or Amerks, as they were commonly referred to) were the second U.S.–based NHL team, pulled together from refugee Hamilton Tigers talent and outside pick-ups. The original and mainstay owner was Bill Dwyer, a famed bootlegger during the Prohibition era; but with the end of the dry years came misfortune for Dwyer, and after an attempted merger with the equally downtrodden Ottawa Senators, the league ended up wresting control away from the former booze baron.

The Amerks were the definition of sad sack for most of their time in the NHL, only making the playoffs once during the first decade of their existence. In the subsequent 13 years, including their final as the Brooklyn Americans, the team only made the post-season four times. By the end of 1941–42, with many of the team’s players having registered for World War II duty, the team suspended operations, and the league denied them re-entry after the war was complete.

So what is it then about the Americans that makes them so regarded? Well, it’s two parts — first, they had decent players at various times during their tenure, including Hall of Famers like Roy Worters, Charlie Conacher, and Nels Stewart; but more importantly, the jersey they wore is so uniquely colourful and their licence plate–like logo look so unmistakably amazing that one can’t help but want to pick up a replica sweater or hockey puck that bears the insignia of the long-gone franchise.