THE REBELS

★ ★ ★

There was no year more influential to the development of North American hockey than 1972. Two key events changed the landscape of the game forever. One was the Canada–Russia Summit Series — the other was the first puck dropping in the World Hockey Association.

The NHL finally had a challenger to its throne in the early 1970s. The new league quickly made its mark with the signing of Bobby Hull to the Winnipeg Jets. Other NHL marquee names like Gerry Cheevers, Frank Mahovlich, and the great Gordie Howe were lured to the WHA, while imported players like Anders Hedberg gave the league an outlet rarely explored by NHL teams at the time, and top prospects like Andre Lacroix, who may have been picked up by NHL clubs, were recruited and chose to suit up in the WHA, which encouraged underagers to join the pro ranks earlier than they could in the NHL.

The very first WHA game took place on October 11, 1972, pitting the Alberta (later Edmonton) Oilers against the Ottawa Nationals. The Oilers took the game 7-4, kicking off a … how shall I say, unique first year. If there was any clear indicator of the trouble that lay ahead for the WHA, it was that the first championship celebration took place without a championship trophy. Instead, the victorious New England (later Hartford) Whalers paraded around the ice with their divisional award. This was just the cap of a forgettable inaugural season, where two teams — the Dayton Arrows and San Francisco Sharks — relocated and another pair — the Calgary Broncos and Miami Screaming Eagles — folded.

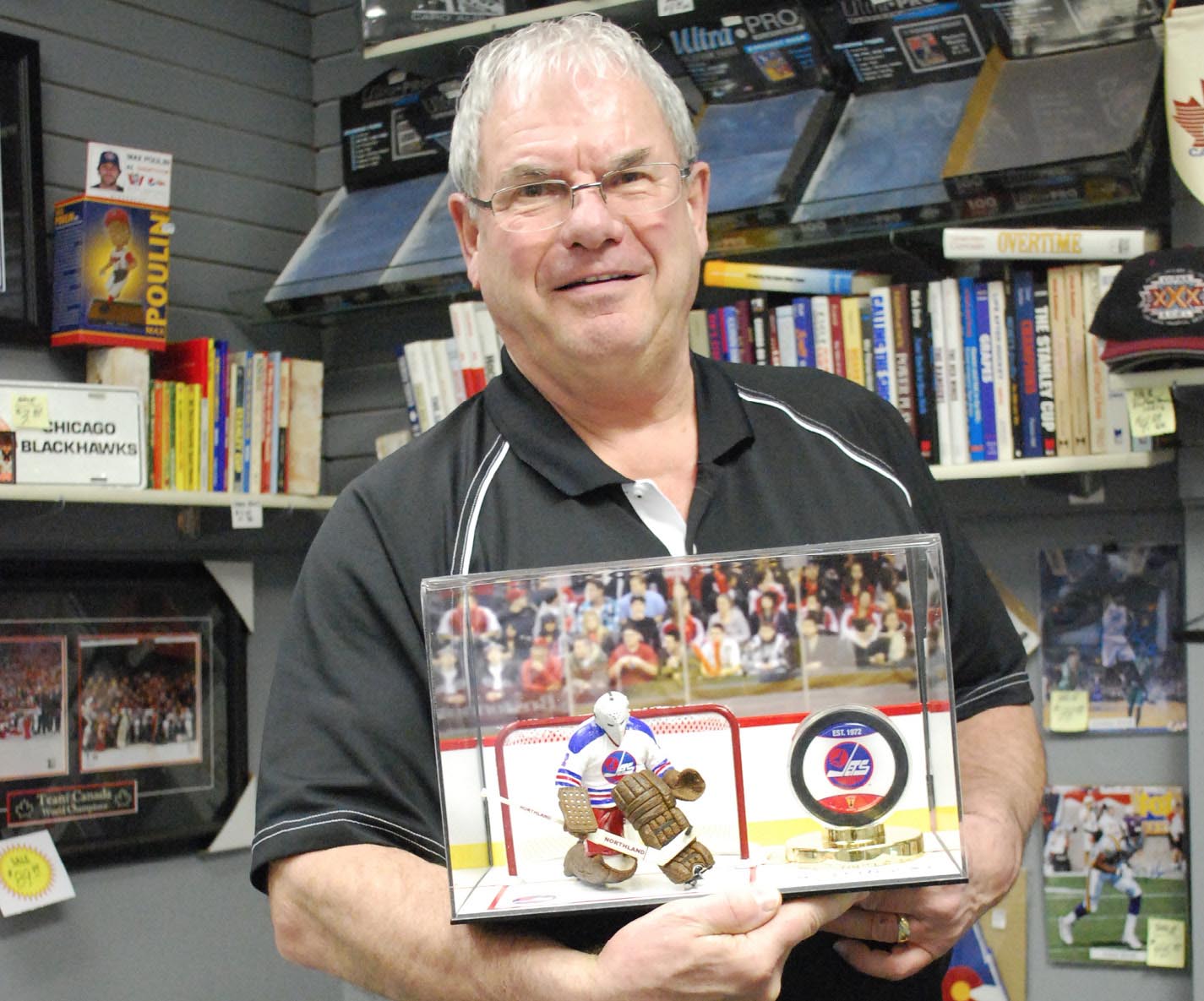

MARC LYNCH

Despite the slippery ice the WHA was skating on, it was able to do something few may have expected — it was able to merchandise its product. Tabletop hockey game company Munro was one buyer. Just as it had done a scant few years earlier, the company produced a game bearing Bobby Hull’s name in 1973, only this game was dedicated solely to the new league. In addition to Munro, the WHA was able to ink a pact with O-Pee-Chee, the signature brand of trading cards for Canadian boys and girls. Originally included in the 1972–73 NHL product line as the final series, the cards featured several of the league’s recognizable (read: former NHL) stars, including Hull and Cheevers. One year later, the WHAers were included in a fold-up poster series in that year’s NHL release before finally breaking out on their own for the 1974–75 season.

This success wasn’t felt across the hockey landscape — the NHL’s brass weren’t quite as willing to work with the new league. Stories of hardships for teams like the Toronto Toros, who clashed with the Maple Leafs over arena issues, emerged. Even before the WHA played its first game, the NHL’s hatred of its competition shone through as WHA stars were not allowed to play in the 1972 Summit Series, even though Hull and others were initially invited to become part of the team. Bitter rivalries between the two leagues were able to be put aside at times, however. For four years, the clubs battled in exhibition contests, with the WHA taking more wins than losses. In particular, the Winnipeg Jets, Quebec Nordiques, and New England Whalers were dominant, while the Edmonton Oilers were the only other club to have a winning record against NHL cubs. While the monetization of those contests in the form of souvenirs was rare, game tickets and souvenir programs do pop up from time to time.

Throughout this time, the WHA continued to have franchise issues, with teams folding or relocating. Almost with every passing season, the makeup of the league changed, at times drastically. By the time the WHA folded, clubs had moved multiple times. For example, the Ottawa Nationals would become the Toronto Toros and then the Birmingham Bulls in the space of the seven-year history of the league. If the hobby community had been alive during this time, one can only imagine the success of the eBay sales of any mementos of these teams.

JOE DALEY. PHOTOGRAPHED BY JON WALDMAN

Despite all this, the WHA fostered and bred the development of future NHL superstars and Hall of Famers. Among them: Michel Goulet, Mark Messier, Mike Gartner, and, of course, Wayne Gretzky. Because of the NHL’s policies on draft eligibility, Gretzky was able to be signed first by a WHA club, and in 1978, Nelson Skalbania picked up the young phenom and brought him to the Indianapolis Racers. Gretzky lasted eight games with the club before his rights were sold to Peter Pocklington and the Edmonton Oilers. As the story goes, Skalbania, who had signed Gretzky to a personal services contract rather than a player agreement, knew the WHA was set to be absorbed by the NHL, and the Racers were not to be one of the lucky teams to survive; indeed, they folded that December.

Soon after Gretzky’s rookie season ended and the Winnipeg Jets captured the Avco Cup Trophy for the third and final time, the leagues officially amalgamated. Despite objections from several NHL team owners, the Jets, Hartford Whalers, Quebec Nordiques, and Edmonton Oilers all joined the NHL — even if they were shells of their former selves. Each team entering the league was permitted to keep only four players (two skaters and two goalies). They were then expected to restock themselves in an expansion draft. The unprotected players were picked up by various NHL clubs.

Since its death, the WHA has maintained a standing in hockey’s history with a subculture of fans that look back fondly on the league. “I wouldn’t use the word cult, but certainly a smaller group of people are quite interested in the WHA,” says Joe Daley, who was between the pipes for the Winnipeg Jets during their days in the rebel league. “I think, over the years, it’s solidified itself as a bona fide league because so many players who got their start there turned out to be Hall of Fame players, which gave it credibility.”

In recent years, the WHA has become the subject of various film documentaries and a number of books. Retro commemorative jerseys, trading cards, and other souvenirs have also become popular for a collecting world anxiously looking for something “different” than the standard product. It perhaps comes as no surprise that the biggest symbol of its unique approach to hockey remains its most in-demand collectible — the blue puck. The non-logic behind using the colourful disk that first season was that it would appear better on TV (the same bit of “fixing something that wasn’t broken” nonsense behind the FoxTrax puck). The experiment lasted only a few months before the league went back to the traditional black slug. Naturally, the blue puck has become a major pursuit of puck collectors, especially those who chase the seemingly rare variants that have a WHA logo on the reverse. Creating confusion around these game pucks, however, was a series produced in 1975 that looked exactly like the originals but were never used in competition. Online hockey museum officialgamepuck.com later got in on the mini memorabilia rush, reproducing the black and original blue slugs with the new WHA logo on the reverse and the series name “Reflections.” (It should be noted, however, that due to licensing issues, some of these pucks, like the Jets version, had slightly altered logos, while others, like the Edmonton Oilers’, were never produced.)

In 2004, as the NHL headed into full-out shutdown mode for the infamous 2004–05 lockout, the Rebel League appeared to be on the comeback trail. With Bobby Hull as one of the key figures, the WHA seemed indeed to be coming back, so much so that Pacific Trading Cards not only signed on as the new league’s official trading card partner but also produced two promotional autographed cards, featuring Lacroix and Hull in the foreground of the new league’s logo. Commemorative pucks and other assorted memorabilia were also produced. All the hype died very quickly, and before a single puck could be dropped, the new WHA became merely a developmental league.