Reflection can be a challenging endeavor. It’s not something that’s fostered in school—typically someone else tells you how you’re doing! Teachers are often so caught up in meeting the demands of the day, that they rarely have the luxury to muse on how things went.

—Peter Papas

Mr. Williams thanked Ms. Adams for her candid and insightful conversations about her students. A small smile seemed to escape from her lips as she concluded the thirty-minute conferral session and headed back to class. Mr. Williams looked around and asked the support staff, “So, how did our first academic conference go?” Everyone was quiet until Ms. Taylor mentioned, “Even though Ms. Adams seemed a little nervous, I noticed that she started to really open up and share a lot about her learning plans and the progress she wants for her students in the coming months.” Mr. Jordan added, “It looks like Ms. Adams is gaining additional perspective from the student data for what can be done for her students to master grade-level standards.” Mr. Williams leaned back and thought the dialogue was helpful and targeted on student progress. He felt this was a big step toward where their school needed to go. It was refreshing to feel like their time together was making progress, that they were going somewhere. But how would the next conference session go with one of the veteran teachers of the school?

Supporting Instructional Leadership

It is important that we spend time discussing the academic progress of our students. Academic conferences provide a venue for focusing on the instructional leadership needed for our schools. We expand our instructional leadership capacities as we openly reflect and consciously consider the academic progress of the students. When the instructional practices and academic progress within each classroom are brought to the surface and shared with one another, then everyone will benefit. Instructional practices that are not shared, or are only shared among grade-level peers, can now spread to all teachers via the academic conference. Classroom-teacher academic conferences are much more than just getting together and chitchatting about things; they are about developing instructional leadership. As coaches and consultants, we (the authors) have had the opportunity to observe many conferencing sessions over the years. It takes a surprisingly small amount of time, but unless there is a clear focus, the conversation can ramble in ways that contribute little to instructional outcomes. Academic conferences provide the freedom for teachers to influence that conversation. That said, the principal and leadership team should structure conferences to ensure that things stay on track. So, let’s tackle just how a conference is done step-by-step.

Academic Planning

Our school systems typically have no forum for focusing on academic planning. The district administration often does budget planning, construction planning, operational planning, compliance planning, personnel planning, and so forth. Rarely does academic planning reach down to the school level beyond gathering teachers together every couple of years to adopt a new curriculum. If the district does have an instructional plan, typically it sits on a shelf at the district office gathering dust. The average teacher has little or no idea what any district instructional documents may say or how they should affect her everyday interaction with students. We need to take the time and devote our energies to creating an academic plan.

Conferral Processes in Classroom-Teacher Academic Conferences

Academic conferences provide a forum for transforming our schools, and they focus everyone’s energy on those processes that will improve student learning. Many students need cohesive instructional actions that will intervene and address their specific academic needs. When principals and district administrators actively confer with those who know our students best (classroom teachers) and coordinate their instructional processes, we can save our struggling students by smoothing over the cracks, bridging the gaps, and carrying them out of academic chasms.

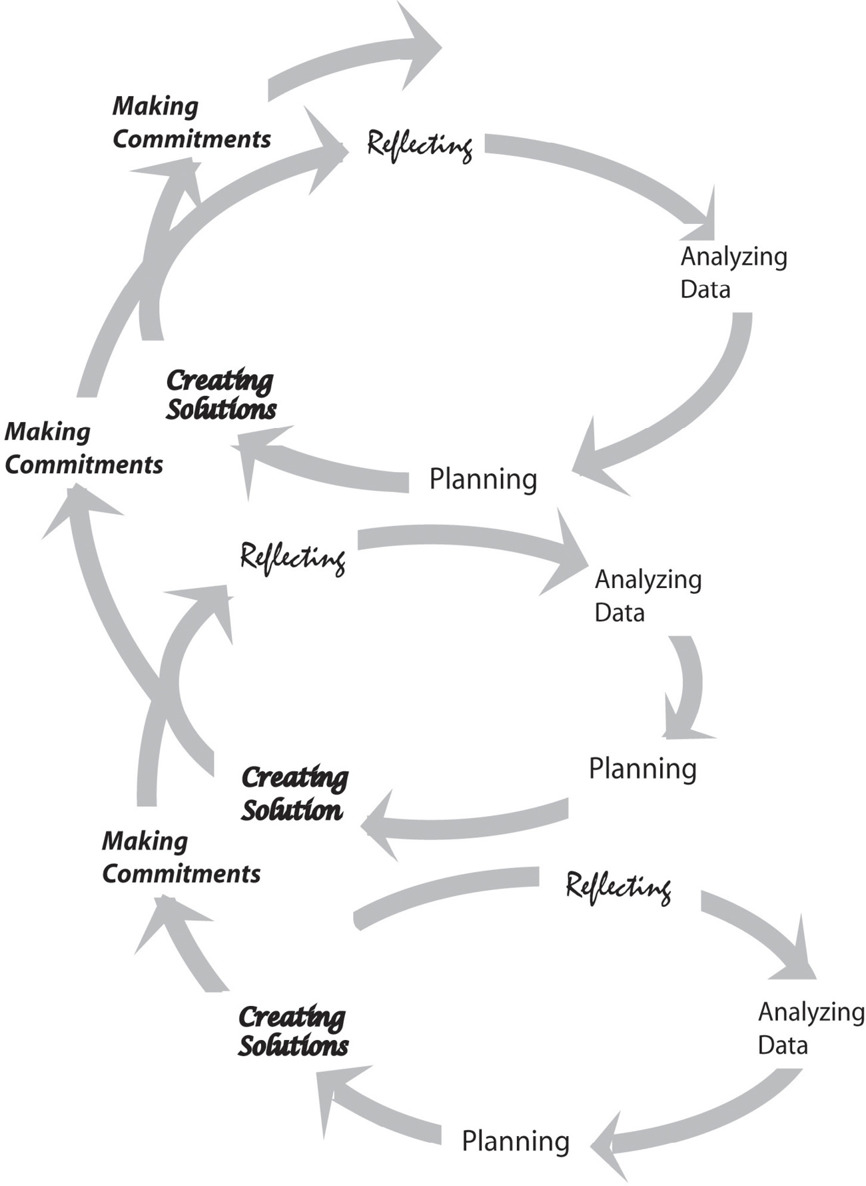

Figure 3.1. The chief contributor selects from five conferral processes as they share their instructional insights in the academic conference.

The five conferral processes are the key elements for academic conferences. They are:

- Reflecting on Instruction

- Analyzing Classroom Data

- Setting Classroom Plans and Goals

- Creating Classroom Solutions

- Making and Confirming Commitments

So let’s look at these five key conferral conversations that provide the main structure of the classroom-teacher academic conference.

Reflecting on Instructional Practices—The academic conference begins with reflection on instruction. The chief contributor or classroom teacher should reflect on academic performance, lessons learned, and insights gained or any other insights that shed light on the instructional experiences with students. We learn things at a deeper level when we take the time to reflect on that experience and use it to influence our future performance. Smith (1994) points out, “Reflection requires space in the present and the promise of space in the future.” We need to take time and provide space to reflect on our present practice, and consider ways that we can infuse that reflection into our academic results to create a positive future for our students. The focus question the facilitator asks helps guide the reflection on instruction in the classroom. The focus question should be asked in a way to help direct reflection, but the teacher should feel free to share any thoughts that shed light on instruction.

Analyzing Student Data—As teachers and principals, our understanding of student needs will increase as we look at the quantitative data (formal assessments, state tests, exit exams, unit tests, etc.) and the qualitative data (classroom observations, survey results, student writing, etc.) to inform our instructional decisions. This data analysis and dialogue about improving future results is vital to increasing academic growth. Anderegg (2007) notes, “Professional development in data analysis for teachers must be directly applicable to their daily practice and linked to specific instructional objectives and goals.” The purpose of analyzing data is to consider objective feedback and see what can be learned about past instructional experiences and what can help influence future instructional activities. The data typically look at the broader picture of how the class is doing. The chief contributor selects five students to focus his efforts on over the next eight weeks or so. This intensive focus provides a qualitative aspect to the progress that is made. Focusing on data provides the academic conferences with feedback and insights into what may work with English language learners, struggling readers, or other types of students who may need particular attention.

Planning Academic Goals—Planning creates a stage for the teachers to clearly understand the goals of the school and to establish their own goals to meet the needs of their individual students. When do district administrators look at the specific needs of school sites? The standard answer is: at a multitude of meetings regarding budgets, operations, and maintenance. We must have a place to sit down and discuss our academic efforts and results. Andy Hargreaves (1998) says, “In some ways, involvement in planning activity is more important than producing plans—it is through collective planning that goals emerge, differences can be resolved and a basis for action created.” The purpose of planning is to establish goals or outcomes that the teacher will focus their instructional efforts on. The classroom teacher should identify at least three specific instructional goals that will improve student learning. The goals may be academic, emotional, and social; the facilitator should only make suggestions if the teacher asks for assistance in establishing classroom goals.

Creating Academic Solutions—Students come to our classrooms bringing with them academic needs. At the same time, the academic bar for performance is being raised higher and higher. Taking the time to identify specific academic solutions is vital for the health of every classroom and every school. The solutions need to come from those closest to the challenge. In our classrooms, that is the teacher. When we focus on solutions rather than problems, we are able to view students in a positive light (Christensen, 2012). The purpose of creating solutions is to engage in a dialogue about challenges that teachers find perplexing as they strive to support student learning. McCuen (1996) points out that “solutions are best developed from a team brainstorming session.” The facilitator can provide ideas for solutions that may be needed to help the classroom move forward to support the learning outcomes for the entire school organization. This step in the academic conference is optional. The key: avoid focusing on students as problems; instead, view the collective efforts of learning as a potential solution to improved outcomes.

Making Academic Commitments—Finally, we need to be open and transparent about the academic priorities and commitments we will make to improve student learning. Academic conferences provide a format for making commitments and following through. These commitments are made by teacher-leaders in the classroom and by principal-leaders in our schools. When everyone meets eight weeks later for the next conference, we can review the progress made on our commitments.

The following statements demonstrate the power of an academic conference practiced correctly. When we have the autonomy to choose the plans and commitments we make, then we achieve at a much higher rate (Rock, 2010). The purpose of making commitments is to ensure that efforts moving forward can be followed up in subsequent conversations and future academic conferences. Poetter and Badiali (2001) note, “People who live and work in learning communities base their actions on shared values, beliefs, and commitments.” The teacher states at least one area for professional growth that he will work on over the next several weeks, and the facilitator makes a commitment to support the professional growth area. The final step of the academic conference is for the facilitator to confirm with the chief contributor that the three plans outlined are commitments he will work on diligently over the next several weeks to improve student learning.

Creating Collaborative Results

Academic conferences can bring together the important players in the school, and they provide a frequent forum for addressing the needs of students and the school.

Academic conferences place the principal, assistant principal, and other site leaders squarely into an instructional leadership role, positioning them as leaders of academic conversations that will make a difference for students.

Figure 3.2. Classroom-teacher academic conference chart of roles

The Conferral Feedback Process

The overall purpose of the academic conference is to create an open dialogue about the key factors that can lead to improved instructional practice, insightful understanding, and educational outcomes. When teachers and support staff engage consistently every eight weeks in the five conferral processes, the result is a cycle of continuous improvement in many areas that leads to increased professional and learning results. The processes of the feedback spiral are powerful in their own right. Reflecting develops a great depth of mutual understanding. Analyzing data develops greater insights into the current reality and opportunities for future progress. Planning and setting three goals creates powerful commitments. Creating solutions builds more confidence; and, lastly, making and confirming commitments creates common bonds and relationships among all involved. Yet, when the conferral processes are woven together, the result is even more powerful. It should be noted that it might take an entire year of conferences to cycle through each phase of the feedback spiral. At the end of the year, the professional stakeholders will have a clear plan and understanding of student data and have solutions and ongoing commitments that will sustain academic success. Classroom-teacher academic conferences provide the principal, school leadership team, and the classroom teacher with the ability to review areas of success and identify opportunities for improvement. The conferencing will help to align programs and determine their effectiveness. In addition, the time spent together will help people become more unified in their understanding and in their resolve to do whatever it takes to improve student learning and classroom instruction. Schein (2004) observes, “The key to learning is to get feedback and to take the time to reflect, analyze, and assimilate the implications of what the feedback has communicated. A further key to learning is the ability to generate new responses; to try new ways of doing things and to obtain feedback on the results of the new behavior.” Academic conferences provide schools and school districts with an effective forum for engaging in feedback spirals that improve academic results. The feedback spiral (adapted from Costa & Kallick, 1995) is a recursive process that frames the important dialogue, discussion, and conversations for instructional leaders.

With three to four academic conferences a year, the feedback spiral provides the framework for improvement that lasts, forming a foundation for further improvement. The feedback spiral is fully complete when every student is learning at grade level and demonstrating proficiency. Academic feedback spirals rely on a variety of data sources to inform the success of the school organization. As teachers, principals, and support staff engage in the conferral feedback spiral, over time they will become better instructional leaders. Their ability to collaboratively reflect, analyze data, plan, create solutions, and make common commitments will increase.

Figure 3.3. The Conferral Feedback Spiral provides the key processes that produce results through academic conferences.

Summary

Classroom-teacher academic conferences harness the academic energy in our schools just as a nuclear core can harness the physical energy contained in an atom. The conferences serve as a unifying force that creates a cohesive academic program. Academic conferences build on several of the major movements of the last decade: professional learning communities, response to intervention, and data-driven analysis, as well as tried and proven practices of professional development. Classroom-teacher academic conferences provide teachers and school principals with a forum for meeting the needs of all students. Conferencing makes a difference for teachers and students, because it serves as a primary mechanism to drive our quest for quality instruction and student learning. Academic conferences provide time to analyze data from students’ assessments. The ultimate benefit of conferencing may be the cumulative understanding of how student learning and instructional leadership progress throughout the school year. Conferencing provides the opportunity to put in place all of the pieces of personal growth, professional collaboration, and powerful interventions of successful classrooms and schools.

REFLECTION QUESTIONS:

- When is the time and space provided to talk about the core issues that affect instruction and student learning in the classroom?

- How can academic conferences improve the implementation, capacity building, and sustainability of academic initiatives in your school?