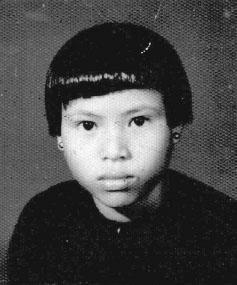

PHUNG THI LE LY’S CLEAREST and earliest memories were of war. One day she and one of her older sisters, Lan, were playing together in the street near their home in Ky La, a village in central Vietnam, when the ground began to shake. All around them screaming villagers ran for cover. Lan grabbed Le Ly and pulled her into a trench by the side of the road and nervously sang:

French come, French come,

Cannon shells land, go hide!

Cannon shells sing,

Like a song all day!

French soldiers occasionally strolled into Ky La, but “even the friendly ones made us sick with horror,” Le Ly wrote later. Part of this was simply due to their differentness: a tall man with Caucasian features seemed terrifying to an Asian child.

The French soldiers were also frightening because they weren’t always so friendly. They knew that many villagers—including Le Ly’s family—were helping the Vietminh and so, to keep them from doing this, French soldiers destroyed village after village. Once, when the French were rumored to be on their way to Ky La, Phung Van Trong, Le Ly’s father, sent his family away to safety. Trong stayed behind and waited for days in a nearby river, knowing that if he was found, he would be accused of being a Vietminh. From a safe distance, he watched the French destroy the village. After they left, he managed to salvage enough furniture and tools to start over.

Trong’s land—and his freedom—meant everything to him. One day, when Le Ly’s five older siblings had moved out and her mother, Tran Thi Huyen, was gone for the day, Trong took his youngest daughter to the top of a hill behind the house where they could see the land all around the village. He told her about the cruel Chinese and French occupations.

“Freedom is never a gift,” he said to Le Ly. “It must be won and won again.”

Le Ly thought he was telling her to become a soldier. Trong laughed. No, he said; her job was to stay alive, help keep the village safe, and care for their large parcel of land so they—like everyone else in Ky La—could continue to grow rice. Then she would have children of her own who could pass on the family stories and tend the shrine of their ancestors. “Do these things well, Bay Ly,” he said, calling her by the name her family members used, “and you will be worth more than any soldier who ever took up a sword.”

But take up a sword she did, at least in play. In 1960, 10-year-old Le Ly and her village friends would often pretend to fight each other in war games. The French were long gone by this time. The new war participants were the Vietcong (VC)—the Communist soldiers secretly fighting in the South—and the soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN)—the soldiers of President Ngo Din Diem’s Southern government. Most of the children wanted to play VCs, even though they weren’t sure at that point if they’d seen one. Le Ly was uncomfortable playing either side: her brother Bon Nghe had gone north in 1954 to join the Vietminh. But her sister Ba, who lived in the nearby city of Da Nang, had married a policeman named Chin who worked for Diem’s government.

The village teacher, Manh, tried to turn his students’ interest—and loyalties—to the Republic of Vietnam. He taught the children songs praising the government and helped them put on plays in which children playing President Diem and his sister-in-law, Madame Ngo Dinh Nhu, always rewarded those who defeated the VC.

Manh would pay the ultimate price for his political views. One evening Le Ly glanced out the window and saw a group of strange men in black clothing rush into Manh’s house. When the strangers came out, one of them was holding a gun to the teacher’s head. They forced him to walk to the road. Le Ly could no longer see them, but she heard Manh begging for his life. Two gunshots silenced him.

The strangers ran a new flag up the schoolhouse flagpole. Their leader, shouting in an accent that sounded odd to Le Ly’s ears, said, “Your children need their education but we will teach them.” Anyone who dared touch the new flag, he threatened, would be shot like Manh, “that traitor.”

The VC had come to Ky La.

ARVN soldiers arrived the next day, pulled down the VC flag, and gave the villagers materials with which to build a defensive perimeter—barbed wire, steel girders, cement. The villagers were directed to dig trenches and build watchtowers from bamboo. Then the soldiers set up ambushes around the village and told the villagers to hide indoors. After waiting and watching for a few days, the ARVN soldiers left.

The VC returned immediately. They destroyed the defensive perimeter. “We are the soldiers of liberation,” their leader said to the assembled villagers. “Ky La is our village now—and yours.”

Which side would win the loyalty of Ky La?

The villagers were somewhat inclined to follow the VC since many of their young men had already gone north. And after arresting, imprisoning, beating, and shooting too many Ky La villagers for suspected VC activity, the ARVN soldiers lost whatever possible allegiance they may have hoped to inspire.

The VC, however, left nothing to chance. While the Ky La adults dug tunnels and bunkers under their homes so that the VC would be able to hide when necessary, the VC gathered the children for instruction. A new enemy, they told the children, had come to Vietnam: the Americans. Just like the French before them, the instructors said, President Diem’s new allies were determined to enslave them.

Le Ly soon came face to face with this new enemy. One day, while caring for the family’s water buffalo, she heard a sudden deafening roar. It grew so loud that the normally lazy animal trotted to the trees to hide.

In the sky, she saw two flying ships “whining and flapping like furious birds.” The wind from these ships blew off her sun-hat. She fell to her knees. She thought she was going to die. Then she raised her eyes. The ship landed. “The dull green door on the side of the ship slid open, and the most splendid man I had ever seen stepped out onto the marshy ground,” she wrote later.

He was enormously tall and fair skinned. “Still cowering, I watched his brawny, blond-haired hands raise binoculars to his eyes,” she wrote. “He scanned the tree line around Ky La, ignoring me completely.” After saying something in a strange language to another man inside the ship, he went back inside.

“Instantly, the flap-flap-flap and siren howl increased and the typhoon rose again,” Le Ly described. “As if plucked by the hand of god, the enormous green machine tiptoed on its skids and swooped away, climbing steadily toward the treetops.”

The next sound she heard was her father’s voice.

“Bay Ly—are you all right?”

“The may bay chuong-chuong—the dragonflies—weren’t they wonderful!” said Le Ly.

Her father scolded her, telling her that she had just seen Americans. But by suppertime, he was no longer angry. In fact, he couldn’t stop smiling.

Le Ly’s mother, Huyen, still terrified by the event, angrily asked her husband to explain his smiling face.

The whole village was talking about Le Ly’s courage, Trong said: she had stood her ground in the presence of the enemy. Le Ly didn’t want to admit that it had been awe, not courage, that kept her from running away. Later she learned that standing still might have saved her life: villagers who ran from American or ARVN soldiers were often shot down for being suspected of VC activity.

The number of Americans in Ky La increased. They tried to win the villagers’ loyalty with food and cigarettes and by caring for wounded civilians at American hospitals. They were also willing to go to great lengths to keep Ky La out of VC control. Americans and ARVN soldiers continuously searched the village for VC hideouts. When they suspected any house of being in the service of the VC, it was burned and the family taken away for questioning. Soon a large portion of Ky La had been destroyed.

This did nothing to deter the VC’s fierce determination to retain their control over what and who remained. “After a while, our fear of the Viet Cong … was almost as strong as our fear of the [ARVN soldiers],” Le Ly wrote later. “If the [ARVN soldiers] were like elephants trampling our village, the VC were like snakes who came at us in the night.”

Part of the way the VC asserted their control over the village was by forcing each villager to take on a specific task. When Le Ly turned 14, her job became sentry duty. She was to stand outside the village keeping watch for ARVN soldiers. If she saw any, she was to walk to a point in front of the village and give a silent signal to another sentry.

While at her post one February morning the following year, a heavy fog limited her vision. She gradually became aware of an odd noise off in the distance. Suddenly, out of the fog marched a large group of ARVN soldiers headed straight for Ky La. Le Ly was now between them and the village.

Terrified though she was, Le Ly realized what she must do: walk along the road in as casual a manner as possible, in front of the soldiers, to the signal point. She carried a bucket while on duty, as a prop. She now used it to collect the occasional potato or berry growing near the road.

Some of the soldiers glanced at her, but none of them stopped to question her. She finally reached the signal point. It was time to relay her message.

While on sentry duty, Le Ly wore three shirts. The outer, brown shirt indicated safety. The second was white and signaled potential danger.

The third shirt was black. It indicated a serious and present threat. Le Ly removed her top two shirts, then resumed picking berries.

She saw a woman approach, carrying a shoulder pole with a bucket on each end. The woman was also a VC sentry. She took one look at Le Ly, put down her buckets, turned around, and rushed away.

Le Ly walked home as quickly as possible, while still in view of the ARVN soldiers, and immediately changed her shirt.

When the soldiers swept the area and found no VC, they suspected that the berry-picking girl they’d noticed on the road might have given away their position. They rounded up several village girls of Le Ly’s approximate age and height, Le Ly included. They blindfolded them, tied their hands behind their backs, then put them on a truck headed for Don Thi Tran prison a few miles away.

Le Ly’s brother-in-law, Chin, personally vouched for her innocence, and she was released.

Back home, Le Ly discovered that the VC had made her a hero and written a song in her honor. They told her to learn it so she could teach it to the village children.

A few days later, holding the song sheet in her hand while resting in a hammock outside the village, she was approached by a group of linh biet dong quan—South Vietnamese Rangers, highly trained special forces who had stealthily entered the area.

One of them grabbed Le Ly by the collar. The song sheet fluttered to the ground. She prayed he wouldn’t see it. But another ranger did. He showed it to the first ranger, who looked at it closely.

“Where did you get this, girl?” he demanded.

Le Ly stammered that she had found it blowing around in the wind. The ranger burned it in front of her, then ordered her hands tied behind her back before he took her to the village. As they walked, she saw other rangers skillfully darting in and out of the bushes and trees.

But shortly after they arrived in Ky La, the rangers went to help local ARVN soldiers battle some VC. When they returned weeks later, the ranger who had burned Le Ly’s song sheet recognized her.

“Didn’t we arrest you on the road a few weeks ago?” he asked.

Terrified, Le Ly tried to deny it.

“Yes,” he said, ignoring her, “you’re the girl with the filthy VC songbook.”

The rangers drove Le Ly and another girl to My Thi, a military-run maximum-security prison outside the large city of Da Nang.

Le Ly was tortured horribly for three days. Then, without explanation, she was released. Her mother was waiting for her at her sister Ba’s house. Huyen told Le Ly that she had used half of her dowry money to bribe an official.

No one had ever returned from My Thi so soon, and the VC in Ky La immediately suspected Le Ly of collaboration with the Southern government. One evening two young VC men took her to a thatched cottage. There a group of 20 VC sentenced her to death. The two young men took her to a freshly dug grave. Le Ly tried to prepare herself for death.

But instead of shooting her, the men raped her. Le Ly was devastated by the traumatic experience, and worst of all, she now worried that no good man would want to marry her, even though she had been sexually violated against her will. And if she didn’t marry, how could she have children and continue her family’s traditions?

The VC men who had raped her would not return her to Ky La, or it would be clear that they had not carried out her death sentence. Instead they took Le Ly to her relatives in a different village and, without explanation, told them she must stay with them.

After her parents discovered where she was, her mother, Huyen, decided to start a new life in Saigon, taking Le Ly with her, while Trong remained in Ky La to care for their land. The mother and daughter first stayed with some former Ky La acquaintances. Le Ly was deeply ashamed that her mother was basically begging these people to take them in. After Le Ly repelled the advances of the teenage boy in the home, the family asked her and Huyen to leave. They found employment and living quarters in the home of a rich Vietnamese family. But when Le Ly—now 16—became pregnant with her employer’s child, they had to move again, this time to Da Nang, where Le Ly’s sister Lan had an apartment.

Le Ly made money selling Vietnamese crafts and black market goods to American servicemen and soon made enough to move her mother and infant son into their own home.

Two years after leaving Ky La, Le Ly returned there to visit her father. She found Trong too weak to get off his bed, his body covered with bruises. The ARVN, he told her, had falsely accused him of killing American soldiers and had tortured him.

Once she felt confident Trong was in stable condition, Le Ly walked to the top of the hill behind their house where her father had once told her Vietnam’s history and her place in it. The whole area, as far as the eye could see, was destroyed and the village empty of people her age. Many young men had been killed. Young women who couldn’t find husbands, not wanting to burden their poverty-stricken parents, had moved to the city for work as housekeepers and hostesses, many of them, including her sister Lan, living with a string of American GI boyfriends. Others had become prostitutes.

Le Ly grieved to think of all the lives the war had destroyed and all the children who would never be born because of it. She wanted to blame someone and told her father so when she reentered the house.

“Are you so smart that you truly know who’s to blame?” Trong asked. Everyone on all sides of the war, he said, had been blaming each other from the start. “Don’t wonder about right and wrong,” he continued. “Right is the goodness you carry in your heart—love for your ancestors and your baby and your family and for everything that lives. Wrong is anything that comes between you and that love. Go back to your little son. Raise him the best way you can. That is the battle you were born to fight. That is the victory you must win.”

After he had recuperated, Trong began to visit Le Ly in Da Nang. During one visit, he was in an exceptionally black mood. The VC, he said, had returned to Ky La. They had given him a message for Le Ly: she was to smuggle explosives into Da Nang’s American military base.

Trong didn’t want her to do it. Le Ly wouldn’t even consider it. But Trong wanted her to know what they had requested, he said, in case something happened to him.

He returned to Ky La. He didn’t wait for the VC to kill him. He took his own life.

In 1969, when she was 19, Le Ly met a 60-year-old American named Ed Munro, a civilian contractor working with the US military in Vietnam. Determined to find a Vietnamese wife, Ed convinced Le Ly to marry him, promising to care for her and her son and to take them away from war-torn Vietnam. They married in 1970, had a baby, and moved to the United States.

When Ed died three years later, Le Ly married a man named Dennis Hayslip, with whom she had a third son.

After returning to Vietnam in 1986 for a visit, Le Ly wrote two memoirs, which Oliver Stone, a filmmaker and Vietnam War veteran, turned into one film called Heaven and Earth.

Le Ly eventually founded two humanitarian organizations, the East Meets West Foundation, now called Thrive Networks, and the Global Village Foundation, both designed to help rebuild her war-torn homeland. She is currently retired, living in Southern California, and working on her third book.

Child of War, Woman of Peace by Le Ly Hayslip with James Hayslip (Doubleday, 1993).

When Heaven and Earth Changed Places: A Vietnamese Woman’s Journey from War to Peace by Le Ly Hayslip with Jay Wurts (Doubleday, 1989).