ON JANUARY 1, 1969, Dr. Dang Thuy Tram recorded in her diary the words of Ho Chi Minh, part of a message he had sent to all those fighting for the Communist cause in the South: “This year greater victories are assured at the battlefront. For independence—for freedom. Fight until the Americans leave, fight until the puppets fall. Advance soldiers, compatriots. North and South reunified, no other spring more joyous.”

Thuy had thought of little else since December 23, 1966, when she had left her beloved family in Hanoi and begun the arduous, dangerous trek down Ho Chi Minh Trail, the network of roads used to support the Vietcong (VC) in the South.

Three months later, Thuy had arrived in Duc Pho, a district in the south-central Quang Ngai Province. The people of Quang Ngai had been heavily involved with resistance against the French during the First Indochina War and were now fighting the Americans and the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) soldiers. Thuy was assigned to work as the chief surgeon in a Duc Pho clinic, saving the lives of VC fighters and North Vietnamese Army (NVA) soldiers so that they could return to the fight.

Dang Thuy Tram. Vietnam Women’s Museum, Hanoi

While Thuy derived great satisfaction from her work, several things caused her intense grief. One was her thwarted attempts to be accepted into the Communist party.

Her motives for wanting to join the party were not like those of many people she knew who simply wanted to advance their careers. Thuy believed that being a party member would allow her to serve the Communist cause more effectively. She recorded in her diary what she believed to be the aims of a true Communist: “Our responsibility is to fight for what is right, to fight for righteousness. To win we must strive, think, and sacrifice our personal gains, perhaps even our own lives…. I will dedicate my lifelong career to securing the rights of the common man and the success of the Party!”

Why wasn’t Thuy allowed into the party? Her parents were educated. Her father was a surgeon who enjoyed Western music, and her mother was a lecturer at the Hanoi College of Pharmacology. Thuy had studied medicine and also enjoyed reading Vietnamese poetry along with French and Russian literature. To her great frustration and sorrow, her educated background branded her as bourgeois—that is, middle class and materialistic—and therefore unworthy of Communist Party membership.

Thuy’s dedicated medical work and obvious devotion to the cause, however, eventually gained the respect of local Communist Party leaders. On September 28, 1968, she was finally accepted, writing in her diary, “My clearest feeling today is that I must struggle to deserve the title of ‘communist.’”

Thuy would also struggle to master her emotions. She found it difficult not to befriend the young men who were risking their lives for Vietnam’s unity. “I have a physician’s responsibilities and should maintain some degree of objectivity,” she wrote, “but I cannot keep my professional compassion for my patients from becoming affection…. Something ties them to me and makes them feel very close to me.” When the men left the clinic, Thuy often felt as if she had lost a family member.

And when she treated the same patients more than once, her attachment to them became even greater. A soldier named Bon came under her care on three separate occasions. Thuy first treated him for a minor leg wound. He was brought to her a second time for a shoulder injury that resulted in a severe loss of blood. Bon was worried that his shoulder might not heal enough to bear the weight of a gun.

It did heal, and after Bon had recovered, Thuy saw him one day from a distance. “Greetings, Doctor!” he cried, waving his healed arm in the air. “My arm is as good as new!”

But on January 9, 1969, Bon was brought once more to the clinic, his clothing soaked with blood. A mine had lacerated his leg. Thuy amputated it, hoping the operation would at least save Bon’s life. It didn’t.

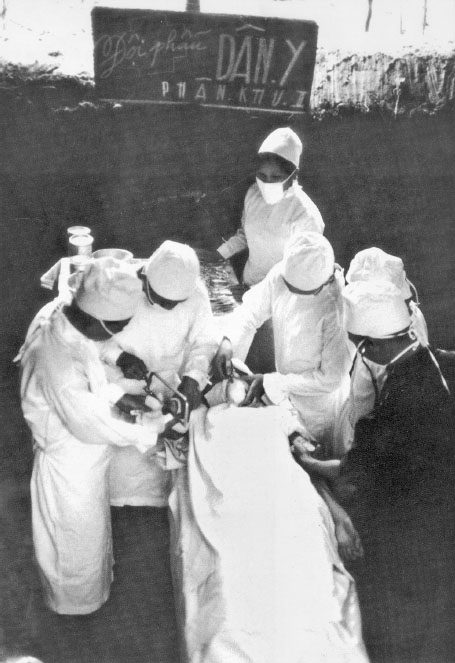

Surgery being performed in a tunnel. Vietnam Women’s Museum, Hanoi

“Oh, Bon, your blood has crimsoned our native land…. Your heart has stopped so that the heart of the nation can beat forever,” Thuy wrote in her diary.

She also recorded a very different emotion on this sad occasion, writing, “Hatred for the invaders presses down a thousand times more heavily upon my heart…. We will still suffer as long as those bloodthirsty foes remain here.”

Two months later, on March 13, Thuy was again saddened by the death of a Communist soldier. She conducted one operation on him, but a second would be necessary to save his life. Although his chances of survival were slim, Thuy wanted to perform the second operation. But she kept this to herself when the rest of the medical team unanimously decided against it. The young man died.

In his pocket, Thuy discovered photos of a girl, a letter promising faithfulness, and a handkerchief embroidered with the words WAITING FOR YOU.

Thuy couldn’t get the young man—or his faithful girlfriend—out of her mind. Again she blamed the Americans for this sorrowful loss, describing it as one of the many “crimes committed by the imperialist killers.”

At the end of March, she was ordered to report to a different clinic, this one treating both civilian and military cases. The new area, as well as most of the others where Thuy had practiced medicine, were “free-fire zones”; that is, civilians considered friendly to Americans had been evacuated, so the Americans considered anyone remaining to be the enemy and could fire on them without previous orders. This meant that whenever any Americans approached, the clinic personnel had to evacuate. On April 28 Thuy described such an evacuation in her diary:

It’s not yet 8:30 a.m., but I urge people to move the injured. I follow them, carrying as many supplies as possible. We trudge up the slope to the school, sweat pouring down our faces, but we dare not pause to rest…. Less than an hour and a half later, a barrage of gunshots goes off nearby, so close to us that it seems the enemy has already reached the guard station. I tell all the patients to prepare for another move. We are not ready to do anything, but our terror-stricken highlander guerrilla brothers rush in, saying that the enemy has reached the irrigation gutter. All the local people are fleeing the area.

Thuy was determined not to abandon any wounded. But toward the end, the only people remaining to help evacuate the patients were a few “skinny, sickly teenagers.” The Americans were almost upon them. Finally, only one patient remained, a man named Kiem, who had a broken leg. The only medics left in the clinic now were Thuy and a petite female medical student. Thuy ran to get help. Two male medics returned with her, telling her “between ragged breaths” that the Americans had shot one of the wounded soldiers. Then the medics helped Thuy carry Kiem into an underground shelter, where they all hid for an hour until the Americans left the immediate area.

By 4:00 that afternoon, the entire clinic—staff and patients—had arrived safely at their new destination.

But they were never really safe. From April 1969 on, the medics and their wounded were constantly on the move as the increasingly intense fighting grew closer. Each day Thuy could hear “the roar of planes tearing the air” while gunshot volleys rang out day and night.

On May 20 Thuy described another brush with death. Several American HU-1A helicopters, which ARVN soldiers used at the time, and a scout plane had circled near the clinic’s location. Thuy was very worried by “the intensity of their search.” The area was then hit with exploding grenades, and the house the medics were using as a patient’s ward filled up with smoke. All the medics and patients rushed into the bunkers under the house. When the helicopter circled away to begin another pass, Thuy rushed back up into the house to save any stragglers. No one was there—all had escaped. She returned to her shelter and waited out the barrage. It lasted an additional 30 minutes. When it was over, the staff moved the clinic to a new location.

Transportation of the wounded in 1968. Vietnam Women’s Museum, Hanoi

But the Americans knew that Communists were in the area. Four days later, Thuy heard an attack of “bombs, bullets, artillery shells, and airplanes,” describing it as “a maelstrom of sounds … usually heard in war movies.” On July 16 she described a similar raid: “Where each bomb strikes, fire and smoke flare up; the napalm bomb flashes, then explodes in a red ball of fire, leaving dark, thick smoke that climbs into the sky.”

During these raids, Thuy always worried about the people she knew and loved. “From a position nearby, I sit with silent fury in my heart,” she wrote. “Who is burned in that fire and smoke? In those heaven-shaking explosions, whose bodies are annihilated in the bomb craters? … Oh, my heroic people, perhaps no one on earth has suffered more than you.”

On July 27 the Americans attacked the hamlet where she was staying. By nightfall, nearly everyone had fled. Thuy walked alone to Pho Quang, a nearby village. It too was deserted. The house she entered was “eerily empty.” The village trees had been destroyed. The smell of gunpowder was in the air. The road was pockmarked with craters from artillery.

Thuy finally located a woman, who told her it would be impossible to follow the rest of the villagers, because of enemy shelling. As if to emphasize her point, an artillery explosion suddenly illuminated the pitch-darkness.

This was an unusually dangerous situation for Thuy. Because Communist surgeons were so valuable in the South, they normally traveled with an armed guard who directed their way. Now Thuy had to navigate for herself, and she wasn’t sure what to do. “If the enemy comes, where should I run?” she wondered.

While Thuy was confused, she rarely feared for her own safety. After she regrouped with the other medics, she was sent out on a nighttime emergency mission and bravely walked through hostile territory with her guard. “Perhaps I will meet the enemy, and perhaps I will fall, but I hold my medical bag firmly regardless,” she wrote in her diary.

She hadn’t yet met the Americans face-to-face, but Thuy had definitely heard them from the underground shelters and bunkers, walking, shouting, and searching for their hidden enemies. When the rainy season began and the underground hideaways filled with water, hiding became increasingly difficult.

Her attempt to stay one step ahead of the Americans soon cast her out of doors, hidden in some bushes, “soaking wet and shivering.” Yet she was happy, even at this moment of difficulty, “to be a part of the resistance, to be in this very scene” with her comrades.

On December 31, 1969, Thuy wrote, “Death is close. Just the other day, if I had been a few minutes late, I would have been dead or captured. We started to run when the enemy was less than twenty meters away. Fortunately, no comrade or wounded soldier was lost.”

But one day she found the body of a dead comrade on the road. Next to him, in the fresh mud, were the prints of large boots. The road was covered with electrical wires from American mines.

On June 2, 1970, Thuy’s new clinic took a direct hit. Five patients were instantly killed, and the surrounding area was devastated. “Trees downed in every direction, houses flattened or knocked askew, tattered clothes blown up in the tree branches,” Thuy described.

Ten days later, the Americans attacked the same group of medics at a different location. No one was injured, but it was frighteningly clear someone had betrayed their location. They had to move again.

The evacuation took place on June 14. Left behind were Thuy, three other female medics, and five seriously wounded soldiers too weak to be moved. They were told to wait until an escort came; it was too dangerous for them to even venture outside.

They waited. One of the wounded fighters, a 19-year-old commando, told the women to run if the enemy came. They were down to their last meal, and still they waited.

Finally, help arrived. Thuy, the other medics, and their patients were evacuated safely.

A few days later, Thuy was walking on a trail with a soldier and two other Vietnamese people when she finally came face-to-face with a group of Americans. Her body was later found by some local villagers. She had been shot in the head.

Her diaries fell into the hands of Fred Whitehurst, an American working for military intelligence. Assigned to destroy enemy documents, Fred was about to throw Thuy’s diaries in a fire when his Vietnamese interpreter, ARVN sergeant Nguyen Trung Hieu, who had read the diaries, stopped him. “Don’t burn this one, Fred,” he said. “It has fire in it already.”

As Sergeant Hieu read the diaries to Fred evening by evening, Fred was powerfully moved. Although he knew he should have turned them in, he kept them when he left Vietnam in 1972.

In 2005 Fred located Thuy’s family and gave them the diaries. Later that year, they were published in Hanoi as one volume, becoming a bestseller. Young Vietnamese people particularly liked the book; they had learned about the war from textbooks and war diaries that described the war in a formal, grandiose style. In contrast, Thuy’s diary presented the unpretentious voice of a warm, intelligent, and occasionally self-doubting young person caught up in the horror of war. Older Vietnamese Communists, who perhaps wondered if the long, destructive war had been worth it in the end, were uplifted by this patriotic young woman’s words:

What agony! Must I keep filling my small diary with pages of blood? But, Thuy! Let’s record, record completely all the blood and bones, sweat and tears that our compatriots have shed for the last twenty years. And in the last days of this fatal struggle, each sacrifice is even more worthy of accounting, of remembering. Why? Because we have fought and sacrificed for many years; hope has shone like a bright light burning at the end of the road.

Vietnamese Communist leaders called the Vietnam War a “struggle for national salvation.” As such, every able-bodied person had to be mobilized, women included. An estimated 1.5 million Vietnamese women were involved in some type of active combat during the war, 60,000 of whom were officially part of the Northern Vietnamese Army. The rest fought in local militias or guerrilla units, many participating part-time in this effort because they were still responsible for food production.

Vietnamese women combat veterans received little recognition until 1995, when the Vietnam Women’s Museum in Hanoi opened. The museum celebrates women warriors throughout Vietnam’s history but places equal emphasis on the traditional female role of motherhood. These two ideals clashed tragically following the Vietnam War when thousands of women veterans were unable to have children: some women had lost their health during the grueling years of combat, and others couldn’t find husbands because too many men their age had been killed.

A militia unit armed with World War II–era German machine guns, most likely captured by the Soviet army. Vietnam Women’s Museum, Hanoi

In 2007 Thuy’s diary was translated into English and published under the title Last Night I Dreamed of Peace.

Even the Women Must Fight: Memories of War from North Vietnam by Karen Gottschang Turner, with Phan Thanh Hao (John Wiley & Sons, 1998).

Last Night I Dreamed of Peace: The Diary of Dang Thuy Tram, translated by Andrew X. Pham (Harmony Books, 2007).

Patriots: The Vietnam War Remembered from All Sides by Christian G. Appy (Penguin Books, 2004).

Portrait of the Enemy: The Other Side of Vietnam, Told Through Interviews with North Vietnamese, Former Vietcong, and Southern Opposition Leaders by David Chanoff and Doan Van Toai (Random House, 1986).