IN THE SOUTHERN VIETNAMESE city of Tien Gang one day in late April 1981, an 18-year-old woman was summoned from her premedical studies classroom. Four men were in the hallway asking for her.

When she came into the hallway, the men just stared at her.

“You are Kim Phuc?” one of them finally asked.

“Yes—I am Kim Phuc,” the girl answered.

“You are the girl in the picture?” the man asked.

“Yes,” she replied. “I am the girl in the picture.”

This woman looked far too normal, too healthy to be the one they sought. The famous photo they spoke of had been taken nine years earlier, on June 8, 1972, during an event that nearly ended the girl’s life.

A few days before the photo was taken, Kim’s family had fled their home because the Vietcong (VC) was pressuring the Phucs to work for them. The Phucs found refuge in a temple with other South Vietnamese families and some soldiers of the Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN). Though the sounds of battle were far away, the soldiers warned that a “big attack” was coming.

Then the distinct smell of explosives became stronger. The sounds of war—planes, helicopters, bursting shells, and machine gun fire—grew louder.

The villagers heard the soldiers cursing: they had just seen one of their own observation planes trail the colored smoke used to identify the presence of VC. Had the pilot seen the enemy in this area? Or had he just made a terrible error?

“Everybody get out!” the soldiers shouted. “They are going to destroy everything!” The soldiers ran in the direction of the American base, urging the villagers on: “Run! Run fast, or you will die!”

Vietnamese photographer Nick Ut, along with a dozen other international journalists, was nearby waiting behind some ARVN barbed wire. They had heard rumors of an impending battle. Nick watched an ARVN Skyraider plane approach. He took a few photos.

Thinking that nothing else notable would occur that day, Nick was about to leave when he noticed something terribly wrong: the Skyraider pilot seemed to be off course. Then he saw a second Skyraider approach, this one “even more off target than the first.”

Although they could tell something was dangerously off-kilter, the journalists knew better than to run away: American or ARVN soldiers might assume anyone running from them was VC and shoot at them. So the journalists stood and watched as the plane dropped a bomb filled with napalm, a sticky, flammable substance that, once ignited, can reach 5,000 degrees Fahrenheit.

Nick focused his camera. He was struck with the fierce beauty of the bomb’s colorful explosion, which covered the highway and the fields in smoke. He wished at that moment that his camera contained color film.

Then he felt the bomb’s intense heat, even though he was standing hundreds of yards away. It felt, he thought, “as if a door had opened on an immense brick furnace.”

The next thing he noticed were screams. They came from inside the smoke.

“People have been bombed!” yelled a Peace Corps worker in the group of journalists.

Out of the smoke emerged screaming women and children running toward the journalists, who snapped photo after photo as they approached.

Then came a naked, screaming girl. Her name was Kim Phuc, and she was nine years old.

When the second plane dropped its napalm, Kim became engulfed in flames. Her clothes burned off. Her left arm was on fire. When she tried to brush the flames with her right hand, it became engulfed in the same burning sensation covering her neck and back.

She heard her brother’s voice and tried to follow it. She stumbled through the smoke screaming: “Nong qua, nong qua!” (Too hot, too hot!)

Nick saw her. As she approached with her brothers in front of her, he snapped a photo. Then he tried to help. He heard the girl asking for water. He repeated her request to whoever could hear him. An ARVN soldier held his canteen to her lips. Other ARVN soldiers emptied their canteens over her back. Nick covered her with a poncho, put her in the news van, then took her and another burned woman to a Saigon hospital.

Then he rushed to have his film developed. On the following day, June 9, 1972, the photo of screaming, naked Kim Phuc running down the road with other casualties of war made the front pages of newspapers worldwide. It would win Nick multiple international prizes, including the American Pulitzer.

Two days after the attack, reporters Christopher Wain and Michael Blakey tried to track Kim down. They found her unconscious at the First Children’s Hospital in Saigon. When they asked a nurse how the girl was doing, the woman answered, “Oh, she die, maybe tomorrow, maybe next day.”

Clearly no one was fighting to save the girl’s life. Christopher and Michael called the American embassy and asked if Kim could be transferred to an American hospital. Yes, said the embassy official, but only if the South Vietnamese foreign ministry gave the OK.

But the official at the foreign ministry hesitated. The transfer might make his government look bad, he said.

Christopher couldn’t believe what he was hearing. “The entire world has just seen the South Vietnamese air force bombing the hell out of their own people, and this would make it worse for you?” he said.

The official agreed to the transfer, and from that day on, Kim received better care.

She had suffered severe burns over 30–35 percent of her body and remained in critical care for a month. The treatment to save her life—daily cleansing in a burn-case bathtub—was horrifically painful to the wounded little girl. Her father stayed at her side night and day; he wanted to be there when she died so he could take her body home.

But Kim didn’t die. After a 14-month stay at the American hospital, she was finally strong enough to return to her war-ravaged home. The Associated Press Bureau in Saigon was inundated with gifts and money intended for “the little girl in the picture.” Nick Ut did what he could to make sure Kim’s father received his daughter’s gifts.

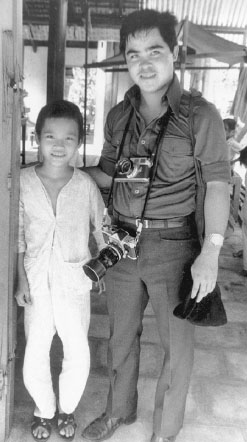

Kim with Nick Ut in 1973. Associated Press

In January 1973 German photojournalist Perry Kretz was under house arrest in a Saigon hotel. His crime? Photographing an ARVN soldier asleep at his post. But before Perry’s visa expired, he was determined to get one more story. He bribed his guard and walked two blocks to the Associated Press office. There he spoke with Peter Arnette, a New Zealand journalist who had won the 1966 Pulitzer Prize for his war reporting. Perry asked Peter if he had any ideas for a good story.

“Kim Phuc is a good story,” said Peter.

“Who’s Kim Phuc?” asked Perry.

“She’s the girl burned by napalm.”

Perry was incredulous. “She’s alive?!”

Perry traveled to her house and took photographs of her. When they walked to the spot where Kim had been hit by the napalm, her smile faded. Was she experiencing bad memories, Perry wondered. No, she told him. It was the heat. The damaged portions of her skin—which now contained no pores or sweat glands—had just overheated.

They returned to the house, and while the little girl cooled off with a shower, Perry, with the family’s permission, took photos of Kim’s scarred back. Then he returned to Germany, and his article was published. But he couldn’t get Kim out of his mind.

And Kim couldn’t get free of the war. There were still occasional incidents during which she had to run for her life because of shelling. In recurring nightmares, she was always running, running, running away from danger. She just wanted the war to end.

On April 30, 1975, it finally did. That morning her uncle Thieu “called for silence” as he tried to hear the news broadcasting from his transistor radio. General Duong Van Minh, Thieu said, was surrendering to the Communists. All South Vietnamese soldiers were to lay down their weapons.

“It’s over,” said Thieu. “The war is over.”

The children cheered. The adults wept. “We lost, we lost, we lost,” they said. Their sorrow was justified: Kim’s father and uncle were soon sent to so-called reeducation camps because the new government had decided they needed to be indoctrinated with Communist ideology. They were released several years later and, like thousands of others Southern Vietnamese people who survived the reeducation camps, returned mere ghosts of their former selves.

The years passed, and during Kim’s final year of high school, she decided on a career in medicine, partly because she remembered the kind doctors and nurses who had worked to save her life. But when she took the pre-entrance university exam, she came two points short of the standard that would allow her into medical school. She would have to take a six-month course in Tien Giang in order to prepare for university work.

On the day in April 1981 when Kim was ushered out of her math class to assure four important-looking men that she was the famous girl in the picture, they seemed surprised. “But, you look very—normal!” said one.

Kim understood. She drew up the sleeve on her left arm. It was covered with scar tissue.

The men left, apparently satisfied they had found the right girl. Kim returned to her classroom, slightly amused but also puzzled. Why the search for her, and why now?

Two days after Kim completed her premedical course and returned home, she began to understand. The same men appeared at her home in a van. They said they were taking Kim to Ho Chi Minh City (Saigon’s new name since 1976) to see their “boss.” They didn’t give her a reason.

When they arrived at their destination, the Information Ministry, an official and writer for the Communist Daily gave Kim an explanation. A German journalist had been looking for her, he said, and had requested the assistance of the Vietnamese government. “He met you 10 years ago and could not forget you.” The government decided to help the journalist and ordered a search for Kim.

A Vietnamese official escorted Kim to a hotel, where she met with three foreign journalists. They asked her what she remembered of the napalm attack and what she had been doing since. Then she was treated to the most extravagant meal she had ever eaten.

Kim was invited to two more interviews with foreign journalists that summer. She didn’t understand why she was being treated like a celebrity, but she enjoyed the attention, even though talking about the napalm attack brought on vivid nightmares.

She was more than ready to put it all behind her, especially when she passed the entrance exam for medical school and moved to Ho Chi Minh City in October to begin her studies. She was thrilled to have a good future ahead of her, unlike many young people in the South: children of families who had served the Southern government in any way were not allowed to attend professional schools.

But to Kim’s great disappointment, the meetings with Western journalists did not stop. During her first week of medical school, she was summoned from her classroom once per week for interviews in Tay Ninh, a province northwest of Ho Chi Minh City. The man who initiated these interviews was a Communist official in his late 50s named Hai Tam. He was undereducated, with only two years of formal schooling, but had been rewarded for his loyal support of the Communist cause during the war with this high-level job.

Each week Tam would invite Western journalists to his office, where he would lecture them on Socialism before allowing them to interview Kim. After each reception, Tam took Kim aside and angrily corrected her on whatever he believed she had said incorrectly. He told her she could say anything about her napalm wounds but nothing that might be perceived as negative about Vietnam’s current government.

After each session, Kim had to find her own transportation from Tay Ninh back to Ho Chi Minh City. Once she asked Tam if she could hitch a ride with the foreign journalists. Tam refused, and Kim knew better than to ask again.

By November, the interviews had increased to twice per week. The minders—that is, the men in charge of collecting Kim for the interviews—were rude and inconsiderate. Sometimes they made her sleep on a cot outside Tam’s office the night before an interview. Kim became increasingly anxious about all the classes she was missing. She did her best to borrow notes from fellow students, but she couldn’t make up necessary hours spent in the laboratory, clinics, and hospitals.

She tried to protest, but it did no good. She asked one journalist why they were all so interested in her story. “You are ‘hot’ news,” he said.

Finally, the inevitable happened. The dean of the medical school told her she would have to drop out.

Heartbroken, Kim pleaded with him to change his mind.

It was impossible. The officials in Tay Minh claimed Kim had become too important and that Ho Chi Minh City was no longer safe for her, he said.

Kim went to see Tam, and he confirmed her suspicions: he had been behind the dean’s decision.

“You cannot go to Ho Chi Minh City to study,” he said. “You are an important victim of the war. I want you here. Your job is to answer the telephone and type for me.”

Kim tried to run away, but when Tam threatened to harm her parents, she went along with his wishes. Interested in learning English, she signed up for a language course in Ho Chi Minh City, but her parents, sinking under ever-growing taxes, couldn’t afford to pay her tuition.

The interviews became more frequent. One of the journalists who came to see her was Perry Kretz. Kim was glad to see him again, but she lied about what she was doing, as she did to all the journalists. Tam had ordered her to pretend she was still a medical student. A Dutch film made at the time actually showed her in a classroom with other medical students. In reality, Kim avoided her fellow students as much as possible; they were now beginning their second year of studies, and she didn’t want to be overwhelmed with jealously.

They have destroyed my life. Why do they do this to me? Why? Kim asked herself one day.

Her physical and emotional health were both deteriorating, but she couldn’t receive the specialized care related to her scar tissue—which still caused intense intermittent pain and exhaustion—because her family wasn’t Communist. But perhaps she could do something about her growing depression, she thought. Longing to feel happy again, she tried to seek a oneness with God through a renewed devotion to the faith she was raised in—Caodai, a Vietnamese religion that combines elements of Confucianism, Taoism, and Buddhism. But her acceptance of her current situation—perhaps the result of sins in her past lives, she thought—and her intense prayers did nothing to alleviate the downward spiral of her emotions. So she went to her library and carefully studied a variety of texts from different religions. She eventually converted to Christianity, discovering in it the inner peace she had been craving. Then she prayed for someone to rescue her. Perry Kretz came immediately to mind.

She wrote him a letter asking for help, knowing very well that if the letter fell into the wrong hands, she and her whole family might be arrested.

Perry received her letter and said to his publishers, “We’ve run her picture and done stories on her many times. Why don’t we do something for her?”

The Vietnamese government allowed him to take Kim to Germany, where she received several operations that greatly eased the pain from her scar tissue.

During this visit, Kim became famous all over again. At a reception at the Vietnamese embassy in Germany, she trusted a kind-looking official with her story, how she was being forced to live a lie. He put her in touch with Vietnam’s prime minister, Pham Van Dong, a kind man, he said, who had been a personal friend of Ho Chi Minh.

When Kim returned to Vietnam and met Prime Minister Pham Van Dong, he took pity on her and had the government pay her tuition to study English in Cuba. While there Kim fell in love with another Vietnamese student, Bui Huy Toan. They married in 1992 and planned to spend their honeymoon in the Soviet Union. But when their plane stopped in Canada to refuel, Kim and Toan remained behind, seeking—and gaining—asylum in that country.

Kim was finally free.

In 1997 she was named a goodwill ambassador for UNESCO, the United Nations Educational, Scientific, and Cultural Organization. That same year, she created the Kim Foundation International, a nonprofit organization whose mission is to provide medical and psychological care to children in war situations.

Fire Road: The Napalm Girl’s Journey Through the Horrors of War to Faith, Forgiveness & Peace by Kim Phuc Phan Thi (Tyndale Momentum, 2017).

“The Girl in the Picture: Kim Phuc’s Journey from War to Forgiveness” by Paula Newton, CNN, June 25, 2015, www.cnn.com/2015/06/22/world/kim-phuc-where-is-she-now/index.html.

The Girl in the Picture: The Story of Kim Phuc, the Photograph, and the Vietnam War by Denise Chong (Penguin Books, 2001).

Kim Phuc Foundation website, www.kimfoundation.com.