APPENDIX

The ‘First Introduction’ to the Critique of Judgement

195

I. Philosophy as a System

IF philosophy is a system of rational knowledge through concepts, this already suffices to distinguish it from a critique of pure reason, for although the latter includes a philosophical investigation into the possibility of this kind of knowledge, it does not form part of such a system, but rather projects and examines the very idea of this system in the first place.

We must begin by dividing the system into its formal and material parts, the first of which (logic) merely treats the form of thought in a system of rules, while the second (the real part) systematically considers the objects that are thought in so far as rational cognition of them is possible through concepts.

Now this real system of philosophy itself can only be divided into theoretical and practical philosophy, in accordance with the original difference in their respective objects and with the essential distinction, deriving from this, in the principles of a science that includes them. One part, therefore, must be the philosophy of nature, the other part the philosophy of morals; while the former may also contain empirical principles, the latter can never contain anything but pure a priori principles (since freedom cannot possibly be an object of experience).

But there is a major and prevailing misconception, one very damaging to the way in which we approach the science itself,* with regard to the meaning of the practical character that permits something to be assigned to practical philosophy. It has been deemed proper to include diplomacy and political economy, the rules of household management, and those of general behaviour, prescriptions concerning diet and the health of body and soul alike (and indeed why not all the arts and professions?) within practical philosophy since all of these contain a body of practical propositions. But while practical propositions are distinguished from theoretical propositions, which contain the possibility and the determinations of things, not by their content but by a difference in the way we represent them, merely those which consider freedom under laws are so distinguished. All the rest are simply applications of the theory of the nature of things to the way in which we can produce them according to a principle, that is to say, their possibility represented as resulting from a voluntary act (which equally belongs to the realm of natural causes). Thus the solution of the problem in mechanics—to discover the respective lengths of the arms of a lever if a given force is to be in equilibrium with a given weight—is certainly expressed as a practical formula, but one which contains no more than the theoretical proposition: in a state of equilibrium the lengths of the arms of the lever are inversely proportional to the former. It is simply that this relationship, since it is an effect of a cause governed (through our own choice) by the representation of that relation, is thought as possible. And the same holds for all practical propositions that are concerned only with the production of objects. If someone offers prescriptions for promoting happiness and discusses, for example, what one must do to be happy, then it is only the inner conditions of the possibility of being happy—temperance, moderation of the inclinations in order not to yield to passion, etc.—which are represented as relevant to the nature of the subject, together with the way we can produce this balance through our own efforts. Consequently, all this is derived directly from the relation between the theory of the object and that of our own nature (ourselves as cause). Since the practical prescription is here distinguished from a theoretical one by its formula rather than by its content, no special type of philosophy is required to investigate such a connection of ground and consequent. In short, all practical propositions which derive what can occur in nature from the power of our own choice as a cause belong to theoretical philosophy as knowledge of nature. Only those propositions which give freedom its law are specifically differentiated by their content from the former propositions. One can say of the first kind that they constitute the practical part of a philosophy of nature, while the latter alone lay the foundation of a special practical philosophy.

196

197

Remark

It is very important to divide philosophy precisely according to its parts, and to that end not to include amongst the members of this systematic division something that is only a consequence or an application of it to given cases and that thus requires no special principles.

Practical propositions are distinguished from theoretical ones either with regard to their principles or their consequences. In the latter case, they do not comprise a particular part of science, but belong to the theoretical part of science as consequences of a particular kind that derive from it. Now the possibility of things under the laws of nature differs essentially and in principle from their possibility under laws of freedom. But this difference does not lie in the fact that in the latter case we locate the cause in a will, while in the former case we locate it in the things themselves external to the will. For if the will obeys no other principles than those in accordance with which, as merely natural laws, the understanding grasps the possibility of the object, and the proposition implying the possibility of something as an effect of the causality of voluntary action can be described as a ‘practical’ proposition, we still cannot claim that this proposition is remotely distinguished, in principle, from the theoretical propositions which concern the nature of things; and it must therefore borrow its principle from the latter in order to present the representation of an object in reality.

198

Thus practical propositions, the content of which concerns merely the possibility of a represented object (through voluntary action), are simply an application of a thorough theoretical knowledge and cannot comprise a special part of a science. A ‘practical’ geometry, considered as a separate science, is a nonsense, however many practical propositions this pure science may contain, most of which, as problems, require special instruction for their solution. The problem of constructing a square with a given side and a given right angle is a practical proposition, but it is purely a consequence of the relevant theory. Nor can the art of surveying (agrimensoria) ever presume the title of a practical geometry or ever be described as a special part of geometry itself, but belongs amongst the scholia of the latter, namely the employment of this science for purposes of commerce.1

Even in a science of nature, in so far as it rests upon empirical principles, namely physics in the proper sense, the practical procedures for discovering the hidden laws of nature, under the name of ‘experimental physics’, can never justify the (equally nonsensical) name of ‘practical physics’ as a part of natural philosophy. For the principles according to which we perform our experiments must themselves always be derived from our knowledge of nature, and thus from theory. And exactly the same is true of the practical precepts concerning the voluntary production of a certain state of mind within ourselves (e.g. the arousing or taming of the imagination, or the pacifying or subduing of the inclinations). There is no practical psychology as a special part of the philosophy of human nature since the principles for a possible, artfully produced, state of mind must be borrowed from those concerning the possible determinations of the character of our nature, and although these consist of practical propositions they still do not comprise a practical part of psychology, but belong simply to its scholia precisely because they possess no special principles.

199

In general, practical propositions (whether they be pure a priori or empirical), if they immediately imply the possibility of an object through our own power of choice, always belong to our knowledge of nature and thus to the theoretical part of philosophy. Only those propositions which directly present the determination of an act as necessary, simply by representing its form (in accordance with laws in general), regardless of the material content of the envisaged object, can and must possess their own special principles (in the idea of freedom), and although the concept of an object of the will (the highest good) is grounded on precisely these principles, this object still only belongs indirectly, as a consequence, to the practical precept (henceforth described as a ‘moral’ one). Moreover, the possibility of the highest good cannot properly be grasped through any knowledge of nature (or theory). Thus it is only such propositions which belong to a special part of a system of rational cognition under the name of practical philosophy.

In order to avoid ambiguity, all of the remaining practical propositions, regardless of the science with which they may be connected, can be called technical rather than practical ones. For they belong to the art of realizing what is envisaged, something which, in the case of a complete theory, is always merely an extension of the latter and never an independent part of any kind of precept. In this sense all precepts of skill are technical2 and therefore belong to our theoretical knowledge of nature and derive from the latter.

200

But in what follows we shall also employ the term ‘technic’* where the objects of nature are merely judged as if their possibility depended upon art. In such cases the judgements are neither theoretical nor practical (in the sense just described) since they determine nothing with regard to the character of the object or to the way in which we produce the latter; rather nature itself is thereby judged, though merely in analogy with art, and indeed in a subjective relation to our faculty of cognition rather than in an objective relation to the objects. Here we shall not indeed describe the judgements themselves as technical, but rather the power of judgement upon whose laws these judgements are grounded, and in conformity with this nature itself will also be called ‘technical’. Since this technic includes no propositions of an objectively determining character, it does not constitute a part of doctrinal philosophy, but only part of the critique of our cognitive faculties.

201

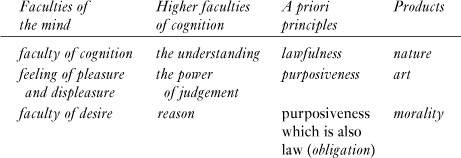

II. The System of the Higher Cognitive Faculties which lies at the Basis of Philosophy

IF we are speaking of the division not of philosophy, but of our faculty for a priori cognition through concepts (the higher faculty), i.e. of a critique of pure reason with respect solely to its capacity for thinking (leaving the pure form of intuition out of consideration), then the systematic representation of the capacity for thought falls into three parts: first, the capacity for knowledge of the universal (of rules)—the understanding; secondly, the capacity for subsuming the particular under the universal—the power of judgement; and thirdly, the capacity for determining the particular through the universal (the derivation from principles)—reason.

The critique of pure theoretical reason, dedicated to uncovering the sources of all knowledge a priori (and thus also of the intuitive aspect which belongs to reason), furnished the laws of nature, the critique of practical reason furnished the laws of freedom, and thus the a priori principles of all philosophy appear to have been entirely dealt with already.

202

But if the understanding furnishes a priori laws of nature, while reason furnishes those of freedom, then we may expect by analogy that the power of judgement, which mediates the relationship of the other two faculties, will likewise afford its own special a priori principles which will perhaps form the basis for a particular division of philosophy, and that the latter, as a system, can only be composed of two parts.

Yet the power of judgement is such a peculiar, and by no means independent, faculty of cognition that it provides neither concepts, as does the understanding, nor ideas, as does reason, for any object whatsoever, because it is merely a power of subsuming under concepts that are given from elsewhere. If, therefore, there were any rule or concept that sprang originally from the power of judgement, it would have to be a concept of things in nature in so far as nature conforms to our power of judgement; it would thus concern that character of nature of which we can form no other concept than that its organization conforms to our capacity for subsuming the particular given laws under more general ones which are not given. In other words, this would have to be the concept of a purposiveness of nature that furthers our capacity to know nature in so far as we must be able to judge the particular to be contained under the universal and to subsume it under the concept of nature as one.

203

A concept of this kind is that of experience as a system in accordance with empirical laws. For although experience forms a system under transcendental laws, which comprise the condition of the possibility of experience in general, one might yet be presented with such an infinite multiplicity of empirical laws and so great a heterogeneity of natural forms in particular experience that the concept of a system in accordance with these (empirical) laws would necessarily appear alien to the understanding, and neither the possibility nor still less the necessity of such a unified whole would be conceivable. Yet particular experience, which is thoroughly coherent under constant principles, also demands this systematic connection of empirical laws through which it becomes possible for the power of judgement to subsume the particular under the universal, while always remaining within the empirical sphere and advancing to the highest empirical laws and the forms of nature that correspond to them. Hence the aggregate of particular experiences must be regarded as a system since without this presupposition no thoroughly lawlike interconnection, i.e. no empirical unity of these experiences,3 could be established.

This lawfulness, which is in itself contingent (as far as all the concepts of the understanding are concerned) and which the power of judgement (merely for its own advantage) presumes and presupposes in nature, is a formal purposiveness of nature which we in fact assume in the latter, but which forms the basis neither for a theoretical knowledge of nature nor for a practical principle of freedom; nonetheless, it provides a principle for judging and investigating nature with regard to the general laws through which we arrange the particular cases of experience in order to bring out the systematic connection required for coherent experience and which we have an a priori ground for assuming.

204

The concept which springs originally from the power of judgement and belongs peculiarly to it is therefore that of nature as art or, in other words, the concept of the technic of nature with respect to its particular laws. This concept does not supply the foundation for any theory and no more implies any knowledge of objects and their characteristics than does logic, but merely furnishes a principle for advancing in accordance with empirical laws through which the investigation of nature becomes possible. This does not enrich our knowledge of nature with any specific objective law, but merely provides the basis for a maxim of the power of judgement, namely to observe in accordance with it and thereby to unify the forms of nature.

205

Philosophy, as a doctrinal system of the knowledge of both nature and freedom, is not endowed with any new division here since this representation of nature as art is a mere idea which serves as the principle for our investigations into nature and thus merely enables the subject to introduce systematic interconnection into the aggregate of empirical laws as such wherever possible in so far as we attribute to nature a relationship to this need of ours. On the other hand, our concept of the technic of nature, as a heuristic principle for judging it, will belong to the critique of our cognitive faculty; this critique indicates what cause we have for representing the technic of nature in this way, what the origin of this idea may be, whether it is to be found in an a priori source, and likewise what the range and limits of its employment may be. In short, such an enquiry will belong to the system of the critique of pure reason, but not to doctrinal philosophy.

III. The System of All the Faculties of the Human Mind

WE can trace all the powers of the human mind, without exception, back to three: the faculty of cognition, the feeling of pleasure and displeasure, and the faculty of desire. Now it is true that philosophers, who otherwise deserve unstinting praise for the thoroughness of their thinking, have sought to explain this distinction away as a purely apparent one and to bring all the faculties under that of cognition alone. But it is very easily demonstrated, and it has already been obvious for some time, that this attempt to bring unity to the plurality of the faculties—one that was otherwise undertaken in a genuinely philosophical spirit—is futile. For there always remains a great difference between representations which belong to knowledge, as related merely to the object and to the unity of our consciousness of these representations, and likewise between the objective relation in which they belong to the faculty of desire when regarded as the cause of the reality of the object, and representations which merely stand in relation to the subject, when they afford their own grounds for merely maintaining their existence in the subject, and to that extent are regarded in relation to the feeling of pleasure. This latter is not a case of knowledge at all, nor does it furnish any knowledge, although it may presuppose something of the kind as a determining ground.

206

The connection between knowledge of an object and the feeling of pleasure or displeasure occasioned by its existence, or the way in which the faculty of desire resolves to bring the object into existence, can certainly be known empirically, but since this connection is not based on any a priori principle, the powers of the mind to that extent constitute only an aggregate rather than a system. Now one can certainly elicit an a priori connection between the feeling of pleasure and the other two faculties, and if we connect an a priori cognition, namely the rational concept of freedom, to the faculty of desire as its determining ground, we can at the same time discover subjectively within this objective determination a feeling of pleasure contained in the determination of the will. But the cognitive faculty is not linked to the faculty of desire in this way by means of pleasure or displeasure since here the pleasure does not precede the latter faculty, but either only follows after its determination or is perhaps nothing but the sensation of this capacity of the will to be determined by reason itself; pleasure therefore is not a particular feeling or a unique form of receptivity which would demand a particular domain for itself amongst the properties of the mind. But since the analysis of the powers of the mind incontestably reveals a feeling of pleasure which is independent of any determination by the faculty of desire and can instead furnish a basis for determinations of the latter, the connection between this faculty and the other two within a single system implies that this feeling of pleasure, like the other two faculties, rests on a priori principles rather than on merely empirical grounds. Thus, for the idea of philosophy as a system, we still require a critique (though not a doctrine) of the feeling of pleasure and displeasure to the extent that is not empirically grounded.

207

Now since the faculty of cognition through concepts finds its a priori principle in the pure understanding (in its concept of nature), and the faculty of desire finds its a priori principle in pure reason (in its concept of freedom), there remains amongst the general properties of the mind an intermediate faculty or receptivity, namely the feeling of pleasure and displeasure, just as there remains amongst the higher cognitive faculties a certain intermediate power, namely that of judgement. What is more natural than to suspect that the latter will also contain a priori principles for the former?

208

Without descrying anything further about the possibility of this connection, we can certainly already recognize here a kind of fitness between the power of judgement and the feeling of pleasure, which can serve as the determining ground for the latter or find such a ground within it. For while the understanding and reason, in the division of the faculty of cognition through concepts, relate their representations to objects in order to acquire concepts of the latter, the power of judgement relates solely to the subject and for its own part produces no concepts of objects. Similarly, while in the general division of the powers of the mind in general both the cognitive faculties and the faculty of desire contain an objective relation to representations, the feeling of pleasure and displeasure, by contrast, is merely a receptivity with respect to a state of the subject; thus if the power of judgement is to determine anything on its own part, this could only be the feeling of pleasure, and conversely, if the latter is to possess an a priori principle at all, this will only be found in the power of judgement.

IV. Experience as a System for the Power of Judgement

WE observed in the Critique of Pure Reason that nature in its entirety, as the sum of all objects of experience, comprises a system according to transcendental laws, ones which the understanding itself furnishes a priori (namely for appearances in so far as, connected in one consciousness, they are to constitute experience). In precisely the same way, experience must also ideally form a system of possible empirical knowledge in accordance with universal as well as particular laws, in so far as this is objectively possible at least in principle. The unity of nature under a principle of the thorough-going connection of everything contained in this sum of all appearances requires this. To this extent we are to regard experience in general as a system under transcendental laws of the understanding, rather than as a mere aggregate.

209

But it does not follow from this that nature is a system that is comprehensible for the human faculty of cognition with respect to empirical laws as well, and that the thoroughgoing systematic interconnection of its appearances in one experience, and thus experience itself as a system, is possible for human beings. For the variety and diversity of empirical laws might be so great that while it would still be possible in part to connect our perceptions in one experience in accordance with particular laws that we happen to have discovered already, it would never be possible to bring these empirical laws themselves together under a common principle, if it were the case, as is perfectly possible (as far as the understanding can tell us a priori), that the variety and diversity of these laws, and of the corresponding forms of nature, were infinitely great and we were thus confronted by a crude and chaotic aggregate revealing no trace of system whatsoever, even if we still had to presuppose a system in accordance with transcendental laws.

For the unity of nature in space and time and the unity of our possible experience are one and the same because the former is a sum of mere appearances (kinds of representation) which only possesses objective reality in experience, and the latter must be possible as a system under empirical laws if we are to think the former as a system (as indeed we must). It is therefore a subjectively necessary, transcendental presupposition that this dismaying and limitless diversity of empirical laws and this heterogeneity of natural forms does not belong in nature, but that, instead, nature is fitted for experience as an empirical system through the affinity of particular laws under more general ones.

Now this presupposition is the transcendental principle of the power of judgement. For the latter is not merely the faculty of subsuming the particular under the universal whose concept is given, but also, conversely, that of discovering the universal for the particular. But the understanding, in its transcendental legislation for nature, ignores the whole manifold of possible empirical laws. It considers only the conditions of the possibility of experience in general with respect to its formal character. In the understanding, therefore, we cannot discover the aforementioned principle of the affinity of particular laws of nature. The power of judgement alone, to which it falls to bring particular laws under higher, though still empirical, principles, while also taking account of the diversity of these laws under the same universal laws of nature, must take such a principle as the basis of its procedure. For in groping about amongst the forms of nature, whose reciprocal agreement with common empirical but higher laws would otherwise be regarded by the power of judgement as entirely contingent, it would be even more contingent if individual perceptions lent themselves so luckily to formulation in terms of an empirical law; but it would be all the more contingent if manifold empirical laws simply happened to be fitted for the systematic unity of our knowledge of nature in a wholly interconnected possible experience, unless, by means of an a priori principle, we presupposed nature to possess such a form.

210

All of the current formulae: nature takes the shortest path—she does nothing in vain—she makes no leaps in the manifold of forms (continuum formarum)—she is rich in species but poor in genera, and so forth, are nothing but this same transcendental expression of the power of judgement that lays down for itself a principle for experience as a system and thus for its own needs. Neither the understanding nor reason can establish such a law of nature a priori. For although we can perhaps see that nature conforms, in its purely formal laws, to our understanding (and thus becomes an object of experience in general), with respect to the plurality and heterogeneity of the particular laws of nature it is free of all restrictions legislated by our faculty of cognition. It is a sheer assumption on the part of the power of judgement, for the sake of its own employment in advancing continuously from particular empirical laws to more general, though still empirical, ones in order to consolidate empirical laws, which establishes that principle. Under no circumstances can such a principle be set to the account of experience since only under this assumption is it possible to order experience in a systematic fashion.

211

V. The Reflective Power of Judgement

THE power of judgement can be regarded either as a mere faculty for reflecting on a given representation, in accordance with a certain principle, for producing a concept that is thereby made possible, or as a faculty for determining an underlying concept by means of an empirical representation. In the first case, we are dealing with the reflective, in the second case, with the determining power of judgement. But to reflect (to deliberate) is to compare and combine given representations either with other representations or with our faculty of cognition in relation to a concept that is thereby made possible. The reflective power of judgement is also what is called the faculty of judging (facultas diiudicandi).

Now reflecting (which even occurs in animals, albeit only instinctively: not in relation to a resulting concept, but to an inclination yet to be determined) requires a principle just as much as the act of determining in which the underlying concept of the object prescribes the rule to the power of judgement and thus assumes the place of the principle.

The principle of reflection upon given objects of nature is that empirically determinate concepts can indeed be found for all things in nature;4 or, in other words, that in the products of nature one can always presuppose a form which is possible under universal laws that are accessible to our knowledge. For if we were not entitled to assume this, and were unable to base our treatment of empirical representations upon this principle, all reflection would be undertaken in a merely blind and random fashion with no legitimate expectation that it could harmonize with nature.

212

With respect to the universal concepts of nature, under which a concept of experience (without particular empirical determination) is possible in the first place, reflection already possesses a guide in the concept of nature in general, i.e. in the understanding. And the power of judgement requires no special principle of reflection, but schematizes nature a priori and applies these schemata to every empirical synthesis, something without which no judgements of experience would be possible. In this case, the power of judgement, in its reflection, is also determining and its transcendental schematism simultaneously serves it as a rule under which the given empirical intuitions can be subsumed.

But for those concepts which have to be found for given empirical intuitions in the first place, and which presuppose a special law of nature through which alone particular experience is possible, the power of judgement requires a peculiar, equally transcendental principle for its reflection. And one cannot in turn refer this power to empirical laws which are already known, something which would transform reflection into a mere comparison with empirical forms for which one already possesses the relevant concepts. For the question is how, by comparing perceptions, one could ever hope to arrive at empirical concepts that capture what is common to a variety of natural forms, if (as is entirely conceivable) nature had bestowed so great a heterogeneity upon the immense variety of its empirical laws, that all, or almost all, comparison would be useless for discovering any coherence or hierarchical order in the plurality of species and genera. All comparison of empirical representations, in order to discover in natural things empirical laws and the corresponding specific forms and, through comparison of these with others, to discover generically corresponding forms, presupposes that nature has observed in its empirical laws a certain economy, fitted for our power of judgement, and a similarity amongst its forms which we can comprehend. And this presupposition, as an a priori principle of the power of judgement, must precede all such comparison.

213

The reflective power of judgement thus works with given appearances to bring them under empirical concepts of determinate natural things not schematically, but technically; not merely mechanically, like a tool controlled by the understanding and the senses, but artistically, according to the universal but nonetheless indeterminate principle of a purposive and systematic ordering of nature. Our power of judgement is favoured, as it were, by the conformity of the particular laws of nature (about which the understanding is silent) to the possibility of experience as a system, which is a presupposition without which we have no hope of finding our way in the labyrinth of the multiplicity of possible particular laws. Thus the power of judgement itself makes the technic of nature into the principle of its reflection a priori, without being able to explain or determine it more precisely or to possess an objective determining ground for the universal concepts of nature (through a cognition of things in themselves), but only in order to facilitate its reflection in accordance with its own subjective laws and needs while remaining in harmony with the laws of nature in general.

214

But the principle of the reflective power of judgement, through which nature is thought as a system under empirical laws, is to be considered merely as a principle for the logical employment of the power of judgement, and while it is indeed a transcendental principle with regard to its origin, it serves merely to regard nature a priori as qualified for a logical system in its multiplicity under empirical laws.

The logical form of a system consists simply in the division of given general concepts (like the concept of nature in general here) through which we think, according to a certain principle, the particular (here the empirical) in its diversity as contained in the universal. If one proceeds empirically and ascends from the particular to the universal, a classification of the manifold is required, i.e. a comparison of several classes each of which is determined by a distinct concept. When the classification is complete with respect to the common characteristic, its subsumption under higher classes (genera) proceeds until one reaches the concept which contains the principle of the entire classification (and constitutes the highest genus). If, on the other hand, one begins with the universal concept, in order to descend to the particular by means of exhaustive division, the procedure is described as the specification of the manifold* under a given concept, since one is moving here from the highest genus towards the lower one (subgenera or species) and from species to subordinate species. Instead of employing the everyday expression that one must specify the particular which stands under the universal, it is more exact to say that one is specifying the general concept since the manifold is here ordered under the latter. This is because the genus, logically considered, is, as it were, the matter or raw substrate which nature works into particular species and subspecies through multiple determinations. Thus one can say that nature specifies itself according to a certain principle (or the idea of a system), on analogy with the way in which jurists use the word when speaking of the specification of certain raw material of their own.5

215

Now it is clear that the reflective power of judgement, given its character, cannot undertake to classify the whole of nature in accordance with its empirical varieties unless it assumes that nature itself specifies its transcendental laws in accordance with some principle or other. This principle can be none other than that of suitability for the faculty of the power of judgement itself in finding sufficient kinship amongst the infinite multiplicity of things under possible empirical laws as to bring them under empirical concepts (classes) and these in turn under more universal laws (higher genera), and thus to arrive at an empirical system of nature. Since this kind of classification is not a matter of ordinary empirical knowledge, but rather an artistic knowledge, nature, in so far as it is thought as specifying itself in accordance with such a principle, is here also regarded as art. The power of judgement thus necessarily carries with it a priori a principle of the technic of nature, which is distinct from the nomothetic of nature through transcendental laws of the understanding since the latter can validate its principle as law, while the former can do so only as a necessary presupposition.6

The special principle of the power of judgement is therefore this: nature specifies its universal laws as empirical ones, in accordance with the form of a logical system, on behalf of the power of judgement.

216

It is here that the concept of a purposiveness of nature arises, and indeed as a characteristic concept of the reflective power of judgement, rather than of reason, since the end is posited not in the object but solely in the subject, and indeed in the subject’s mere capacity for reflection. We describe something as ‘purposive’ if its existence seems to presuppose an antecedent representation of the thing in question. But natural laws that are so constituted and interrelated as if the power of judgement had designed them to satisfy its own requirements resemble the case in which the possibility of things presupposes the representation of them as a ground. Thus the power of judgement, by means of its principle, thinks a purposiveness in nature in the specification of its forms through empirical laws.

It is not these forms themselves, however, that are thereby thought as purposive, but only their relation to one another and their fitness, even in their great multiplicity, for a logical system of empirical concepts. Even if nature revealed to us no more than this logical purposiveness, we should still have cause for admiring nature in this regard since we are unable to find any ground for this in the universal laws of the understanding themselves. Yet hardly anyone but a transcendental philosopher would be capable of such admiration, and even he could identify no determinate case where this purposiveness is manifested in concreto, but would have to think it solely in general terms.

VI. The Purposiveness of Natural Forms as so many Particular Systems

217

THAT nature, in its empirical laws, should so specify itself as is requisite for the possibility of experience as a single system of empirical knowledge, implies that this form of nature contains a logical purposiveness, i.e. that of its conformity with the subjective conditions of the power of judgement concerning the possible coherence of empirical concepts in the totality of one experience. But this does not entitle us to infer any adaptation of nature to a real purposiveness in its products, i.e. to the generation of individual things as systems. For these could always be mere aggregates, as far as intuition can tell, and still be subject to empirical laws which cohere with others in a logically divisible system without having to assume for their individual possibility a specially identified concept and thus a teleology of nature as their basis. It is in this way that we regard earths, stones, minerals etc. as mere aggregates and devoid of any purposive form, but as nevertheless so related in their inner character and the grounds of their possibility as objects of knowledge that they lend themselves to classification as a system of nature under empirical laws, even though in themselves they display no systematic form.

By an absolute purposiveness of natural forms I therefore understand that external configuration or internal structure of such forms which are so constituted that their possibility is necessarily grounded in an idea of the same within our power of judgement. For purposiveness is conformity to law on the part of something which is contingent. Nature works mechanically, as mere nature, in producing aggregates, but it works technically, i.e. artistically, in producing systems, for example, crystals, all sorts of flower forms, or the internal structure of plants and animals. The difference between these two ways of judging natural beings lies simply in the reflective power of judgement which certainly can and perhaps must proceed to do what the determining power of judgement (governed by principles of reason) does not concede to the latter with respect to the possibility of objects, and it might be the case that the determining power of judgement is capable of tracing everything back to a mechanical explanation. For it is quite possible that the explanation of a given appearance, governed by objective principles of reason, may be mechanical, while the rule for judging the same object, according to subjective principles of reflection, may be technical.

218

In fact the principle of the power of judgement, namely the purposiveness of nature in the specification of its universal laws, may not extend so far that we can infer the production of natural forms that are purposive in themselves (because even without them the system of nature under empirical laws, which is all that the power of judgement is justified in postulating, is possible), and this is something that must always be given through experience; but since we have reason to suppose a principle of the purposiveness of nature in its particular laws, it is still always possible and permissible, if experience shows us purposive forms amongst its products, to ascribe this to the same ground on which the first type of purposiveness may rest.

Even though this ground itself might lie in the supersensible and wholly transcend the domain of our possible insights into nature, we have nevertheless accomplished something in so far as the power of judgement offers us a transcendental principle of the purposiveness of nature in relation to the purposiveness of natural forms which we encounter in experience. If this is not sufficient to account for the possibility of such forms, at least it still permits us to apply such a special concept as that of purposiveness to nature and its conformity to law, even though this principle cannot be an objective concept of nature but is simply derived from the subjective relation of nature to one of the faculties of the mind.

VII. The Technic of the Power of Judgement as the Ground of the Idea of a Technic of Nature

219

AS we have shown above, it is the power of judgement which first makes it possible, and indeed necessary, to think, in addition to the mechanical necessity of nature, a purposiveness in nature. Without this assumption systematic unity in the complete classification of particular forms under empirical laws would be impossible. We have shown, in the first place, that the principle of purposiveness, being only a subjective principle of the division and specification of nature, determines nothing with regard to the forms of nature’s products. In this respect, the purposiveness in question would remain merely conceptual and would supply a maxim suggesting the unity of empirical laws of nature for the logical employment of the power of judgement in experience, furthering the application of reason to its objects. But there would be no natural products, as such, whose form corresponds with this particular kind of systematic unity, namely that according to a representation of an end. The causality of nature with respect to the form of its products as ends I would describe as the technic of nature. It is opposed to the mechanism of nature, which consists in the connection of the manifold without any concept underlying the specific character of this connection, just as certain lifting devices, such as a lever or an inclined plane, which can also exercise their intended effect as a means to an end without presupposing any idea, are called machines rather than products of art because while they can indeed be used purposively, their possibility is not dependent upon this use.

The first question at this point is this: how can the technic of nature be perceived in its products? Precisely because it is not a category, the concept of purposiveness is in no way a concept that is constitutive of experience, and nor is it any determination of an appearance appropriate to an empirical concept of the object. We perceive purposiveness in our power of judgement in so far as it merely reflects upon a given object, perhaps on the empirical intuition of the same, to bring it under some (as yet undetermined) concept, or upon the concept of experience itself, to bring the laws it contains under common principles. Thus it is essentially the power of judgement that is technical. Nature is therefore represented as technical only to the extent that it harmonizes with this procedure and makes it necessary. We shall shortly indicate how the concept of reflective judgement, which makes possible the inner perception of a purposiveness of representations, can also be applied to the representation of the object as contained under it.7

220

Now to each empirical concept there belong three acts of the spontaneous faculty of cognition: 1. the apprehension (apprehensio) of the manifold of intuition; 2. the synthesis, i.e. the synthetic unity of the consciousness of this manifold in the concept of an object (apperceptio comprehensiva); 3. the presentation (exhibitio) in intuition of the object corresponding to this concept. The first act requires imagination, the second requires reason and the third requires the power of judgement which, where an empirical concept is involved, is the determining power of judgement.

But since in simple reflection on perception it is not a question of reflecting on a determinate concept, but in general only of reflecting on the rule concerning perception as an aid to the understanding, as a faculty of concepts, it is evident in the case of a merely reflective judgement that the imagination and the understanding are regarded in their necessary relationship to one another with respect to power of judgement in general, in contrast to their actual relationship in a given perception.

If, then, the form of a given object in empirical intuition is such that the apprehension of its manifold in the imagination agrees with the presentation of a concept of the understanding (regardless of which concept), then in simple reflection the understanding and the imagination harmonize with one another for the furtherance of their work and the object is perceived as purposive with respect to the power of judgement alone. The purposiveness itself is therefore considered as merely subjective since a determinate concept of the object is thereby neither required nor produced, and the judgement involved is not a cognitive one. Such a judgement is called an aesthetic judgement of reflection.

221

If, on the other hand, empirical concepts and laws conforming to the mechanism of nature are already given, and the power of judgement compares such a concept of the understanding with reason and its principle of the possibility of a system, then if this form is encountered in the object the purposiveness is judged to be objective and the thing is called a natural end, since in the previous case things were only judged to be indeterminately purposive natural forms. A judgement on the objective purposiveness is called teleological. This is a cognitive judgement, but it belongs only to the reflective and not to the determining power of judgement. For in general the technic of nature, whether it be merely formal or real, is only a relation of things to our power of judgement, in which alone we can find the idea of the purposiveness of nature that we attribute to nature itself merely in relation to that power.

VIII. The Aesthetic of the Faculty of Judging

THE expression ‘an aesthetic kind of representation’ is completely unambiguous if we understand it to signify the relation of the representation to the object as appearance with a view to the cognition of the object. For in this case the expression ‘aesthetic’ means that the form of sensibility (i.e. how the subject is affected) is necessarily attached to the representation and is thus unavoidably transferred to the object (though only as phenomenon). Consequently there can be a transcendental aesthetic* as a science that belongs to the faculty of cognition. It has long been customary, however, to describe a mode of representation as ‘aesthetic’, i.e. as sensuous, also to signify our intention of relating a representation not to the faculty of cognition, but rather to our feeling of pleasure and displeasure. Although we are also accustomed (in accordance with this nomenclature) to calling this feeling a ‘sense’ (a modification of our state), since we lack an alternative expression, it is nonetheless not an objective sense the determination of which is employed for cognition of an object (for to intuit or otherwise perceive something with pleasure is not a simple relation of the representation to the object but rather involves a receptivity on the part of the subject); on the contrary, it contributes nothing whatsoever to our knowledge of objects. There can therefore be no aesthetic science of feeling, as there is indeed an aesthetic of the faculty of cognition, because all the determinations of feeling are of purely subjective significance. A certain ambiguity, therefore, inevitably clings to the expression ‘aesthetic kind of representation’ if it is understood now to mean that which arouses pleasure or displeasure and now to concern merely the cognitive faculty, in so far as it involves sensuous intuition, with regard to the knowledge of objects as appearances.

222

This ambiguity can, however, be removed if we apply the expression ‘aesthetic’ neither to intuition nor to the representations of the understanding, but solely to the acts of the power of judgement. An aesthetic judgement, if we intended to employ it for objective knowledge, would be so blatantly contradictory that this expression is a sufficient insurance against misinterpretation. For intuitions can indeed be sensuous, but judgements certainly belong only to the understanding (taken in the broader sense), and to judge aesthetically or sensuously, in so far as this purports to be knowledge of an object, is therefore a contradiction where sensibility meddles in the affairs of the understanding and (through a vitium subreptionis)* gives a false direction to the latter. An objective judgement, by contrast, is always brought about through the understanding alone and cannot therefore be called an aesthetic one. Consequently our transcendental aesthetic of the faculty of judgement was certainly able to speak of sensory intuitions, but could never speak of aesthetic judgements because, since it is concerned solely with cognitive judgements that determine an object, all of its judgements must be logical ones. The expression ‘an aesthetic judgement of an object’ therefore signifies that a given representation is indeed related to an object, but such a judgement conveys the determination of the subject and its feeling rather than that of the object. As far as the power of judgement is concerned, the understanding and the imagination are regarded in relationship with one another, and this relationship can be considered (as happened in the transcendental schematism of the power of judgement) as objective and cognitive. But this same relationship of two cognitive faculties can also be regarded purely subjectively, in so far as one of them helps or hinders the other in the selfsame representation and thereby affects the state of the mind, and is thus a relationship that can be sensed (something encountered in the independent employment of no other faculty of cognition). Now although this sensation is not a sensuous representation of an object, it can nonetheless be ascribed to sensibility since it is subjectively connected with the sensuous rendering of the concepts of the understanding through the power of judgement, as a sensuous representation of how the state of the subject is affected by an act of that faculty. A judgement can be termed ‘aesthetic’, i.e. sensuous (according to its subjective effect rather than to its determining ground), even though an act of (objective) judging is an act of the understanding (as a higher faculty of cognition in general) rather than one of sensibility.

223

Every determining judgement is logical because its predicate is a given objective concept. A merely reflective judgement about a particular object, however, can be aesthetic if the judgement, even before it contemplates comparing the object with others, and with no concept antecedent to the given intuition, unites the imagination (which merely apprehends the object) with the understanding (which produces a general concept) and perceives a relationship between the two cognitive faculties which forms the subjective and merely sensitive condition of the objective employment of the power of judgement (namely the mutual harmony of these two faculties). But an aesthetic sensuous judgement is also possible, where the predicate of the judgement cannot be a concept of an object because it does not belong to the cognitive faculty at all, as in the example: ‘The wine is pleasant’—for here the predicate expresses the relation of a representation directly to the feeling of pleasure, and not to the faculty of cognition.

224

An aesthetic judgement can thus in general be defined as that kind of judgement whose predicate can never be cognitive, i.e. involve a concept of an object, although it may contain the general subjective conditions for cognition in general. Sensation is the determining ground in this kind of judgement. But there is only one unique, so-called, sensation which can never become the concept of an object, and this is the feeling of pleasure and displeasure. This is purely subjective since, by contrast, all other sensations can be employed with a view to cognition. An aesthetic judgement, therefore, is one whose determining ground lies in a sensation that is immediately connected with the feeling of pleasure and displeasure. In an aesthetic judgement of the senses it is that sensation that is immediately produced by the empirical intuition of the object, whereas in aesthetic judgements of reflection it is that sensation produced in the subject by the harmonious play between the two cognitive faculties of the power of judgement, the imagination and the understanding, when the former’s capacity for apprehension and the latter’s capacity for presentation reciprocally further one another in a given representation. In such a case, this relation, merely through its form, causes a sensation which is the determining ground of a judgement. This judgement is consequently described as ‘aesthetic’ and is connected with the feeling of pleasure as subjective purposiveness (without a concept).

Whereas aesthetic judgements of the senses express material purposiveness, aesthetic judgements of reflection express formal purposiveness. But since aesthetic judgements of the senses do not relate to the faculty of cognition at all, but only relate immediately through the senses to the feeling of pleasure, it is only aesthetic judgements of reflection that we can regard as grounded on principles peculiar to the power of judgement. For if reflection upon a given representation precedes the feeling of pleasure (as the determining ground of the judgement), then the subjective purposiveness is thought before it is felt in its effect; and in that respect an aesthetic judgement belongs, by virtue of its principles, to the higher faculty of cognition, and indeed to the power of judgement under whose subjective but universal conditions the representation of the object is subsumed. But since a merely subjective condition of a judgement permits no determinate concept of its determining ground, this ground can only be furnished through the feeling of pleasure, though in such a way that the aesthetic judgement is always a judgement of reflection. This is the case because, by contrast, a judgement that assumes no comparison of the representation with the cognitive faculties and their cooperative effect in the power of judgement is an aesthetic judgement of the senses. The latter also relates a given representation to the feeling of pleasure (though not by means of the power of judgement and its principle). It is only in the treatise itself that the characteristic feature which allows us to specify this difference can be identified, namely the claim of the judgement to universal validity and necessity. For if an aesthetic judgement inevitably implies the latter, it thereby also claims that its determining ground must lie not merely in the feeling of pleasure and displeasure alone, but equally in a rule belonging to the higher cognitive faculties, and here specifically in a rule belonging to the power of judgement, which thereby legislates a priori with respect to the conditions of reflection and demonstrates autonomy. This autonomy, however, is not objective (like that of the understanding with respect to the theoretical laws of nature, or that of reason concerning the laws of freedom), i.e. by means of concepts of things or of possible actions, but is merely subjective and valid for a judgement derived from feeling, a judgement which, if it can lay claim to universal validity, indicates its origin as based upon a priori principles. We should properly have to describe this legislation as heautonomy since the power of judgement furnishes the law neither for nature nor for freedom but solely for itself, and is not a faculty of producing concepts of objects, but only of comparing specific cases with concepts supplied to it from elsewhere and of stating the subjective conditions of the possibility of this connection a priori.

225

It is precisely this which also explains why judgement, when it is merely reflective and is not based upon a concept of the object, is expressed in an act which is immediately related only to sensation (something which transpires with no other higher faculty) and which, like all sensation, is always accompanied by pleasure or displeasure, instead of consciously relating the given representation to its own rule. And this is because the rule itself is only subjective, and agreement with it can only be recognized in something which also merely expresses a relation to the subject, namely sensation, as the characteristic feature and determining ground of the judgement. This is why it is also called an ‘aesthetic’ judgement, so that all our judgements can be divided, according to the order of the higher cognitive faculties, into theoretical, aesthetic, and practical ones, where under aesthetic judgements only those of reflection are to be understood since they alone are related to a principle of the power of judgement, whereas by contrast aesthetic judgements of the senses are immediately concerned solely with the relation of representations to inner sense considered as a feeling.

226

Remark

IT is especially important at this point to elucidate the explanation of pleasure as a sensuous representation of the perfection of an object. According to this explanation an aesthetic judgement of the senses or one of reflection would invariably be a cognitive judgement of the object since perfection is a determination that presupposes a concept of the object. Hence a judgement attributing perfection to an object could not be distinguished from other logical judgements, except perhaps, as some allege, through the ‘confused’ character attaching to the concept (which is how some presume to describe sensibility). But this can never constitute any specific distinction amongst judgements. For otherwise a countless host of judgements, not only those belonging to the understanding but also especially to reason, would also have to be described as aesthetic because an object is thereby determined through a confused concept, as in judgements concerning right and wrong since few people (even including philosophers) possess a clear concept of what right is.8 A sensuous representation of perfection is a contradiction in terms, and if the harmonious unification of the manifold is to be described as perfection this must be represented through a concept if it is properly to bear the name of perfection. If one were to regard pleasure and displeasure as nothing but a cognition of things through the understanding (though one unconscious of its own concepts), and claim that they only seem to be mere sensations, then we should have to describe this way of judging things as entirely intellectual rather than as aesthetic (sensuous); the senses would then basically be nothing but a judging understanding (albeit one without sufficient consciousness of its own acts) and the aesthetic kind of representation would no longer be specifically distinguished from logical kind of representation. And since the boundary between the two could never be drawn with precision, this difference of nomenclature would be quite useless. (No mention will be made here of this mystical way of representing the things of the world, one which recognizes no sensuous intuition distinct from concepts and thus leaves it with nothing but an intuitive understanding.)

227

But one might still ask: does not our concept of the purposiveness of nature mean exactly the same as what is affirmed by the concept of perfection,* and is the empirical consciousness of subjective purposiveness, or the feeling of pleasure we take in certain objects, not simply the sensuous intuition of a perfection, as some like to explain pleasure in general?

My answer is this: perfection, as the mere completeness of a plurality in so far as it together constitutes a unity, is an ontological concept which is the same as that of totality (allness) of a composite (through coordination of the manifold in an aggregate, or its simultaneous subordination as a series of grounds and consequences) and has nothing whatsoever to do with the feeling of pleasure or displeasure. The perfection of a thing with respect to the relation between its manifold and the concept of the thing is only formal. But if I speak of a perfection (and there can be many such in a thing grasped under the same concept), it is always grounded in the concept of something as an end to which the ontological concept of the unification of the manifold is applied. This end need not, however, be a practical end, one which presupposes or includes a pleasure in the existence of the object, but can also belong to technic; it thus concerns merely the possibility of things and is the conformity to law of an intrinsically contingent combination of the manifold in the object. As an example we may consider the purposiveness which is necessarily thought in the possibility of a regular hexagon for it is entirely contingent that six equal lines on a plane should intersect at precisely equal angles and this lawlike combination presupposes a concept which, as a principle, makes it possible. This kind of objective purposiveness observed in things of nature (and especially in organized beings) is now thought as objective and material and necessarily carries with it the concept of an end of nature (actual or imputed) in relation to which we also attribute perfection to things; judgement in this regard is called ‘teleological’ and carries with it no feeling of pleasure whatsoever, just as the latter is not to be looked for in any judgement that concerns mere causal connection.

228

The concept of perfection as objective purposiveness thus has nothing whatsoever to do with the feeling of pleasure and the latter has nothing whatsoever to do with the former. For judging the former a concept of an object is necessarily required, whereas for judging the latter no concept is needed and purely empirical intuition can suffice. The representation of subjective purposiveness in an object, on the other hand, is even the same as the feeling of pleasure (without involving an abstracted concept of any purposive relation) and there is a great gulf between these two kinds of purposiveness. If what is subjectively purposive is to be objective as well, a much more far-reaching investigation is required, not only of practical philosophy but also of the technic, whether it be that of nature or of art. That is to say: to find perfection in a thing requires reason, to find a thing agreeable only requires the senses, to encounter beauty in a thing requires nothing but reflection (devoid of any concept) upon a given representation.

229

The aesthetic faculty of reflection thus judges only about the subjective purposiveness (not the perfection) of the object, and the question now arises whether it judges only by means of the pleasure or displeasure which is felt here, or whether it even judges about the latter, so that the judgement simultaneously determines that pleasure or displeasure must be combined with the representation of the object.

This question, as we have already indicated, cannot yet be decided adequately at this point. It is only through the exposition of such judgements, furnished in the treatise itself, that we shall be able to conclude whether or not they possess a universal validity and necessity which permits them to be derived from a determining ground a priori. In that case, a judgement would indeed determine something a priori by means of the sensation of pleasure or displeasure, but it would also simultaneously determine something a priori through the faculty of cognition (namely the power of judgement) by means of the universality of a rule for combining the feeling with a given representation. On the other hand, if a judgement contained nothing but the relation between the representation and the feeling (without the mediation of any cognitive principle), as is the case with an aesthetic judgement of the senses (which is neither a cognitive judgement nor a judgement of reflection), then all aesthetic judgements would belong in the merely empirical domain.

For the moment we can note that no transition from cognition to the feeling of pleasure takes place through concepts of objects (in so far as the latter are to relate to that feeling), and that we cannot therefore expect to determine a priori the influence which a given representation exercises on the mind; and further, as we already noted in the Critique of Practical Reason, that the representation of a universal lawfulness of willing must simultaneously determine the will and thereby also awaken the feeling of respect, as a law contained, and indeed a priori contained, in our moral judgements, even though this feeling still cannot be derived from concepts. In the same way we shall see that aesthetic judgements of reflection contain the concept of a formal but subjective purposiveness of objects, resting on an a priori principle which is fundamentally the same as the feeling of pleasure, but which cannot be derived from any concepts to whose possibility in general the power of representation stands in relation when it affects the mind in reflecting on an object.

230

An explanation of this feeling, considered in general and without distinguishing whether it accompanies sense perception, reflection, or a determination of the will, must be transcendental.9 It can be expressed as follows: pleasure is a state of the mind in which a representation is in harmony with itself, as a ground for simply preserving this state itself (for the state in which the powers of the mind mutually further one another in a representation does preserve itself) or else for producing its object. In the first case, the judgement concerning the given representation is an aesthetic judgement of reflection. In the second case, however, it is an aesthetic-pathological or aesthetic-practical judgement. It can readily be seen here that pleasure and displeasure, since they are not kinds of cognition, cannot be explained in their own right, and ask to be felt rather than understood; and that one can only explain them, and then only inadequately, through the influence which a representation exercises by means of this feeling upon the activity of the powers of the mind.

231

232

IX. Teleological Judging

BY the term formal technic of nature’ I intended to express the purposiveness of nature in intuition, whereas by the term ‘real technic of nature’ I understand the purposiveness of nature in accordance with concepts. The former yields purposive structures for the power of judgement, i.e. a form in the representation of which the imagination and the understanding are spontaneously and reciprocally harmonious with respect to the possibility of a concept. The latter indicates the concept of things as natural ends, i.e. as things whose inner possibility presupposes a purpose, and therefore a concept, which is the underlying condition of the causality of their production.

The power of judgement itself can provide and construct purposive forms for intuition a priori when it devises such forms for apprehension as are suitable for the presentation of a concept. But ends, i.e. representations which are themselves regarded as conditions for the causal production of their objects (as effects), must in general be given from elsewhere before the power of judgement concerns itself with harmonizing with the conditions of the manifold; and if there are to be any natural ends, we must be able to regard certain things in nature as if they were products of a cause whose activity could only be determined through a representation of the object. But we cannot determine a priori precisely how, and in what variety of ways, things are possible with respect to their causes since for this we require knowledge of empirical laws.

A judgement concerning purposiveness in things of nature as a ground of their possibility (as natural ends) is called a teleological judgement. Although a priori aesthetic judgements are not possible, we nonetheless encounter a priori principles in the necessary idea of the systematic unity of experience, and they include the concept of the formal purposiveness of nature for our power of judgement; and this reveals a priori the possibility of aesthetic judgements of reflection that are based upon a priori principles. Nature is necessarily harmonious, not merely with respect to the agreement of its transcendental laws with our understanding, but also with respect to the agreement of its empirical laws with the power of judgement and the capacity of the latter to present an empirical apprehension of the forms of nature by means of the imagination. This agreement simply serves for the furtherance of experience, and the formal purposiveness of experience with respect to the ultimate harmony of nature (with the power of judgement) is thereby revealed as necessary. But if nature, as the object of teleological judgement, is also to be thought in agreement with the causality of reason, under the concept of an end which reason fashions for itself, then that is more than can be attributed to the power of judgement alone; the power of judgement can, of course, contain its own a priori principles for the form of intuition, but not for concepts of the production of things. The concept of a real end of nature thus falls completely beyond the scope of the power of judgement, taken simply on its own. For the latter, as a separate cognitive power, considers only how two faculties (the imagination and the understanding) are related in a representation prior to the formation of a concept and thereby perceives the subjective purposiveness of the object for its apprehension (through the imagination) by the cognitive faculties. Thus in the teleological purposiveness of things as natural ends, which can only be represented through concepts, the power of judgement will have to relate the understanding to reason (something unnecessary for experience in general) in order to be able to represent things as ends of nature.

233

The aesthetic judging of natural forms might, without supplying a concept underlying the object, discover simply through intuitive and empirical apprehension certain objects occurring in nature to be purposive, i.e. merely in relation to the subjective conditions of the power of judgement. Aesthetic judging would therefore neither require a concept of an object nor produce one; that is why it would not interpret these objects in an objective judgement as natural ends, but merely as purposive under a subjective relation to the power of representation. This purposiveness of forms can be called figurative, and the technic of nature with respect to these forms can also be designated accordingly (technica speciosa).*

234

On the other hand, teleological judgement presupposes a concept of the object and judges the possibility of the latter according to a law that connects cause and effect. This technic of nature might therefore be called plastic, if this word were not already now commonly used with reference both to natural beauty and to the purposes of nature. Thus one could, if one wishes, also call it an organic technic of nature, an expression which then designates the concept of purposiveness not merely for the mode in which we represent them but also for the possibility of the objects themselves.

The most essential and most important thing for this section, however, is the demonstration that the concept of final causes in nature, which separates the teleological judging of nature from judging it in accordance with universal mechanical laws, is a concept which belongs merely to the power of judgement and not to the faculties of understanding or reason. Thus if the concept of natural ends were also to be employed in an objective sense, as an intention of nature, this employment would already be sophistical and could never be grounded within experience. For although experience exhibits ends, nothing can demonstrate that these are also intentions, and thus anything pertaining to teleology that is encountered in experience contains nothing but the relation of its objects to the power of judgement, and in fact to a fundamental principle of the latter, through which it legislates for itself (and not for nature)—namely as the reflective power of judgement.

The concept of ends and of purposiveness is indeed a concept of reason, in so far as one attributes to reason the ground of the possible existence of an object. But the purposiveness of nature, or even the concept of things as natural ends, places reason into relation with these things as their cause, although through experience we have no knowledge of the ground of the possibility of things. For it is only in products of art that we can become aware of the causality of reason with respect to objects, which are therefore called ends or described as purposive, and to call reason ‘technical’ in this regard conforms to our experience of the causality of our own powers. But to represent nature as technical on analogy with reason (and thus to ascribe purposiveness, and thus even ends, to nature) involves a specific concept which can never be encountered within experience, and which is only introduced by the power of judgement in its reflection upon objects in order to organize experience, as indicated by this concept, under specific laws, namely those of the possibility of a system.

235

For all purposiveness in nature can be regarded either as natural (forma finalis naturae spontanea) or as intentional (intentionalis). Experience on its own justifies only the first way of representing purposiveness, while the second is a hypothetical way of explaining it which goes beyond any concept of things as natural ends. The former concept of things as ends of nature originally belongs to the reflective power of judgement (as logically rather than aesthetically reflective), while the latter belongs to the determining power of judgement. In the first case reason is certainly also required, albeit only for the sake of experience that is to be organized in accordance with principles (thus in its immanent employment), whereas the second case requires reason to lose itself in extravagant demands (in its transcendent employment).

We can and should endeavour, to the best of our ability, to investigate nature as causally connected in experience according to purely mechanical laws, since it is these which furnish the true grounds of physical explanation and their interconnection constitutes rational scientific knowledge of nature. But amongst nature’s products we find specific and very widely distributed genera which contain within themselves a connection of efficient causes that we can only ground in the concept of an end if we wish to have ordered experience at all, i.e. observation according to a principle that is adequate to their inner possibility. If we were to judge their form and its possibility merely according to mechanical laws, where the idea of the effect must be regarded not as the ground of the possibility of the cause but rather the reverse, it would be impossible, simply from the specific form of these natural things, to derive an empirical concept which would allow us to pass from this inner structure, as cause, to the effect, since the parts of these machines are the cause of the effect which they manifest not in so far as each part has a separate ground of its own, but only in so far as they all share one common ground of their possibility. It is entirely contrary to the nature of physico-mechanical causes that the whole should be the cause of the possibility of the causality of the parts, for the parts must already be given if we are to grasp the possibility of a whole on the basis of the latter; and further, the particular representation of a whole, a representation that precedes the possibility of the parts, is a mere idea and is called an ‘end’ if it is regarded as the ground of a causality. Thus it is clear that if there are such products of nature, it is impossible to investigate their character or their cause even within experience (let alone to explain them through reason) without representing their form and their causality as determined according to a principle of ends.

236

Now it is clear in such cases that the concept of an objective purposiveness of nature serves merely to assist reflection on an object, and not its determination through the concept of an end, and that a teleological judgement concerning the inner possibility of a product of nature is a merely reflective, not a determining judgement. Thus when we say, for example, that the crystalline lens in the eye has the purpose of focusing, through a secondary refraction, the light rays emanating from a certain point into a point on the retina, we are merely saying that we think the representation of a purpose in the causal action of nature in producing the eye because such an idea serves as a principle for conducting our investigation concerning this part of the eye, and thus also assists us to devise possible means of enhancing the relevant effect. But this does not yet involve attributing to nature a causality in accordance with a representation of ends, i.e. an intentional action, which latter would involve a determining teleological judgement, and as such a transcendent one, that introduces a causality lying beyond the bounds of nature.