Coming to Terms with Your Memory

In This Chapter

- The brain can be a trickster

- Understanding how memories are made

- How to remember what you learn about memory

- Sleep, memory’s silent partner

- The truth about false memories

- Exploring the mystery of repressed memory

For a while, stories about people recovering repressed memories were all over the news. Then came reports that some of these recovered memories were false. How is it possible to remember something that never happened? And how does a repressed memory happen, anyway?

Memory distortion research has clearly shown that information that happens after the event, such as stories other people tell us about what happened, can actually be incorporated into our memory. And studies have given us lots of insight into the process by which the mind buries memories we find difficult or painful.

In this chapter, we take a look at the myths and realities of memory: how memory normally works and when and why it doesn’t. We’ll look at some ways we can improve our memory and how research into false memory and repressed memory has improved our understanding of both of these phenomena.

Until he was 15, Swiss child psychologist Jean Piaget believed his earliest memory was of nearly being kidnapped at the age of 2. He remembered vivid details of the event, such as sitting in his baby carriage and watching his nurse defend herself against the would-be kidnapper. He remembered the scratches on his nurse’s face and the short cloak and white baton the police officer was wearing as he chased the kidnapper away.

However, the kidnapping never happened. When Piaget was in his mid-teens, his parents received a remorseful letter from his former nurse, confessing she had made up the whole story and returning the watch she had been given as a reward. Piaget’s memories were false; what he actually “remembered” were the many accounts of this story he heard as a child. He imagined what he thought had happened, and projected this information into the past in the form of a visual memory.

The Memory as Court Jester

Your brain can store 100 trillion bits of information, so why can’t you remember the name of the person you sat next to in homeroom during high school? If your brain is a kingdom, surely your memory can be the court jester. It’s always playing tricks. You can, for example, instantly recall things you never tried to learn (such as popular song lyrics), and you can easily forget things you spent hours memorizing (like material you studied for an exam). Often we remember the things we want to forget and forget the things we wish to remember.

Whether you want it to or not, your brain stores all kinds of information categorized into two types: implicit memory and explicit memory. Implicit memory holds all those trivial facts, song lyrics, and general nonsense your brain files away while you’re concentrating on something else. Explicit memory is the information you consciously process.

DEFINITION

Implicit memory is your ability to remember information you haven’t deliberately tried to learn. Explicit memory is your ability to retain information you’ve put real effort into learning.

Learning About Remembering from Forgetting

Better to have the memory of an elephant than the memory of a human being. Members of our species constantly forget, misremember, and make mistakes. However, these mistakes offer valuable clues about how memory normally works. For example, researchers have found that people forget for one of three reasons:

- They don’t grasp the information to begin with.

- They had it, but they lost it.

- They have it, but they can’t find it.

These mistakes reflect a failure in one of the three mental operations necessary for memory: encoding, storage, and retrieval.

For instance, I simply can’t seem to remember a high school classmate’s name, even though I sat next to her for years. Chances are, my memory failure is due to a retrieval problem—I have her name filed someplace but can’t seem to open the right filing cabinet. If someone gave me a hint, I could probably come up with it. This hint would be a retrieval cue—information that will help me to find and open the right cabinet.

On the other hand, if I had been so self-absorbed in high school that I never learned my classmate’s name in the first place, my inability to come up with it now would be an encoding problem. One clue that a memory failure is due to encoding is the ineffectiveness of hints or clues to prompt memory. If I never knew that my classmate’s name was Denise Johnson, she could tell me her nickname, her initials, and her astrological sign—and I still wouldn’t have a clue.

Alternatively, maybe during my high school years I was a social climber and Denise didn’t fit my idea of the popular crowd. Maybe I learned Denise’s name long enough to ask her for a favor but then didn’t think it was important to remember. In this case, my failure to remember her name would be due to a storage problem.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Amnesia is the partial or complete loss of memory and can be caused by physical or psychological factors. A traumatic event can trigger psychologically based amnesia; memory almost always returns after a few days. Soap operas aside, very rarely does a person lose her memory for a significant portion of her life.

When teachers give tests, they aren’t just measuring students’ capacity for learning. They’re also measuring the ability to remember what was learned. The way students are tested can have a lot of influence over the results because different types of tests engage their retrieval system differently.

Encoding, storage, and retrieval are the three mental operations required for memory. If you can’t recall the items on your grocery list but could recognize the items among a list of foods, your recognition is better than your recall. Recall questions give fewer cues than recognition questions and thus seem harder.

The Long and Short of It

Think of memory in terms of threes. The three mental processes of memory—encoding, storage, and retrieval—happen at least three times as the information makes its way through the three memory systems: sensory memory, working memory, and long-term memory.

Have you ever noticed how you can still hear the sound of the television right after you turn it off? That’s your sensory memory. Sensory memories capture impressions from all our senses. If the impression is a sound, the memory is called an “echo,” while a visual sensory memory is called an “icon.”

Sensory memory holds an impression a split second longer than it’s actually present, to ensure you have time to register it. Its goal is to hold information long enough to give you a sense of continuity but short enough that it doesn’t interfere with new information coming in. However, what our sensory memory lacks in endurance, it makes up for in volume. If I showed you a card with a lot of words on it for only a fraction of a second, you could only say about four of the words before you started forgetting the rest. However, you’d be able to identify out as many as nine because we can remember words faster than we can say them!

PSYCHOBABBLE

Jill Price is a woman who remembers everything that ever happened to her and whose memories keep playing back in random order. She has described her memory as a series of videotapes of her life, randomly playing back different events. She has been diagnosed with a rare disorder called “hyperthymestic syndrome.”

The Organic Data Processor

Short-term or “working” memory has more stamina than sensory memory, but it only lasts for about 20 seconds. It works through and sorts information transferred from either long-term memory or from sensory memory. When information enters our working memory, it has already been processed into meaningful and familiar patterns for later retrieval. However, retrieval can be imperfect. For example, when subjects are asked to recall lists of letters they have just seen, they’re much more likely to confuse letters that sound similar—like B and T—than letters that look familiar.

Working memory preserves recent experiences or events. Because it is short term, its capacity is limited. When the items are unrelated, like the digits of a telephone number, we can hold between five and nine bits of information in our short-term memory. There are, however, strategies that expand our working memory—such as rehearsing. When you look up a phone number and repeat it before you dial, you’re using a rehearsal strategy to enhance your working memory.

INSIGHT

Use it or lose it? New research suggests that five minutes of math a day can help ward off the negative mental effects of aging. Don’t like math? Try some crossword puzzles, or read a few pages out loud.

The Curious Curator

Just as a museum curator takes care of historical artifacts, our long-term memory collects and stores all the experiences, events, facts, emotions, skills, and so forth that have been transferred from our short-term memory. The information ranges from your mom’s birthday to calculus equations. Essentially, the information in long-term memory is our library of all that we have perceived and learned; without it, we’d be lost.

Long-term memory stores words, images, and concepts according to their meaning and files them next to similar words and concepts already in our memory.

BRAIN BUSTER

Coffee jump-starts short-term working memory. After being dosed with 100mg of caffeine (approximately two cups of coffee), participants showed improved short-term memory skills and reaction times. But be careful; drinking coffee to excess can cause anxiety, the jitters, and lower concentration.

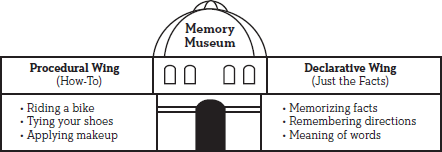

Visiting the Memory Museum

We all have different “artifacts” in our individual mental museums, but the structure of our museums looks remarkably similar to each other. Think of your long-term memory museum as having two wings, with each holding different kinds of information. These wings are actually two types of long-term memory: procedural and declarative.

I Was Only Following Procedure

The procedural wing of your memory museum stores how-to information. Remembering how to ride a bicycle, tie your shoelaces, and put on your makeup are all stored in your procedural memory. All the skills you learn consist of small action sequences, and it’s these skill-related memories that get implanted in your long-term memory.

Skill memories are amazingly hardy. Even if you haven’t ridden a bicycle in 30 years, the memory comes back quickly once you sit on the seat and put your feet on the pedals. The frustrating thing about skill memories, though, is that they are difficult to communicate to others. Ask a gold-medal gymnast to tell you exactly how she does her routine on the balance beam, and she can’t. And if she tries to consciously think it through while she’s doing it, chances are her performance won’t be as good.

Well, I Declare!

Declarative memory, on the other hand, deals with the facts. It’s the part of our memory that enables us to succeed in school, do well at Trivial Pursuit, and win friends and influence people. Unlike procedural memory, declarative memory requires conscious effort, as evidenced by all the eye rolling and facial grimaces we see on the faces of people taking their SATs. Remembering the directions to the dance studio is an example of declarative memory; remembering how to dance is procedural.

The declarative wing of your memory museum has two rooms, one for episodic memory and the other for semantic memory. Episodic memory stores autobiographical information, such as thoughts, feelings, and things that happen to us. Semantic memory is more like an encyclopedia; it stores the basic meanings of words and concepts.

When autobiographical information enters long-term memory, it’s tagged with a time stamp and the context in which it took place—a kind of marking that doesn’t happen with procedural memory. When you do remember when or where you learned semantic information, it’s often because an emotional experience was attached to it. My brother remembers when and where he learned his multiplication tables because he was rapped on the knuckles several times for not practicing them as part of his third-grade homework. Sometimes episodic memory can greatly assist semantic recall!

PSYCHOBABBLE

Research indicates that all of us have some degree of amnesia. Most of us can accurately recall what has happened in the last half of our lives. If you’re 20 years old, you can remember clearly the past 10 years. If you’re 60, your memory’s good for the last 30. Your 10-year-old child can recall the last 5. For most of us, the rest is a blur.

Now, Where Did I Put That Thought?

It happens to most of us about once a week. We see someone we’ve known for years, yet his name suddenly eludes us. We remember other things about this person, like where we met or past conversations we’ve had. But, temporarily, his name escapes us. Frustrated, we exclaim, “It’s right on the tip of my tongue!”

The tip-of-the-tongue experience is a temporary retrieval problem. Long-term memory may store information, but we still have to find it when we need it. Retrieval failure demonstrates two important concepts in long-term memory—accessibility and availability. Long-term memories may be available somewhere in our mental filing cabinet, but we can’t always access them.

Generally, when you’re trying to retrieve a memory, you’ll simply use retrieval cues—mental or environmental prompts that help you retrieve information from long-term memory. For example, the options presented in multiple-choice questions help you recognize learned material. Retracing your steps is another useful retrieval aid—especially when you lose something like your car keys.

Retrieval cues work because they capitalize on your memory’s natural tendency to organize and store related concepts and experiences together. And, as you’re about to see, you wouldn’t have so many retrieval failures if you encoded memories right in the first place.

INSIGHT

Bad at names? Use the person’s name out loud three times in the first few minutes after meeting, and you are much more likely to remember it later.

Will You Gain Wisdom or Grow Senile?

Many elderly people consistently list memory loss as one of the most critical problems they face. Are their complaints accurate? That depends on what kind of memory they’re talking about. For example, aging has relatively little effect on short-term memory. Young adults and seniors differ, on average, by less than one digit in the number of numbers they can hold in short-term memory.

It’s the information transferred from short-term into long-term memory that elderly adults have in mind when they complain about forgetfulness. Their most common complaint is forgetting the names of people they’ve met recently. Laboratory tests (using lists of words to be remembered) reveal that a moderate decline in memory for recent events accompanies normal aging. Some elderly adults remember as well as many young adults, indicating that this decline is a general pattern and not the inevitable fate for every person over 60.

Long-term memory for remote events (things that happened years ago) is pretty consistent over time. All of us forget personal information at some point during the first five to six years after it’s been acquired. What’s left after that usually sticks around. In general, elderly adults do have more trouble remembering some things—like when they last took pain medication (temporal memory) and where they left their umbrella (spatial memory). But if they use cues as reminders, they’re no more absentminded than the rest of us.

INSIGHT

If an elderly person seems to show true memory problems, it is important to get an evaluation by a physician. Many medical conditions can mimic Alzheimer’s: vitamin deficiency, small strokes, even depression. And many of these conditions are treatable.

A Method for Remembering

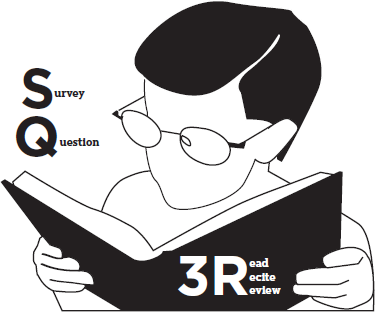

The way we put information in has a lot to do with how easily we can get it out. Since long-term memory stores information logically and meaningfully, it makes sense to organize information when you first encode it in memory. For instance, let’s say you’re really interested in the psychology of memory and want to maximize the chances that you’ll remember the information in this chapter. One of the best encoding strategies was developed by Francis Robinson in 1970. It’s called the SQ3R method: Survey, Question, and Read, Recite, and Review.

How does it work? Let’s use this book chapter as an example. First, survey the chapter—take a quick look and get an idea of how it’s organized. Second, develop some questions about each subheading.

Then read the chapter, and write down the answers to the questions you had. After that, without looking, recite out loud those answers you wrote down. Now, review all the material again, and keep reciting information out loud.

The SQ3R method makes the most of your long-term memory’s natural organizer. Surveying helps your brain get organized. Questioning assists in breaking the information down into manageable chunks and also makes it more meaningful to you. Reading, reciting, and rehearsing all work to store the information. And, of course, taking the time to use these encoding strategies helps you overcome one of the critical personality traits that leads to forgetfulness—plain, old-fashioned laziness!

INSIGHT

Getting ready for a high-school reunion? Look over that yearbook, and you’re sure to be very popular. Forty-eight years after graduation, students were only able to recall 20 percent of their schoolmates’ names. But after looking at old photos, they could name them 90 percent of the time.

Hooked on Mnemonics

“Use i before e except after c.” “Thirty days hath September, April, June, and November.” “In 1492, Columbus sailed the ocean blue.” These are examples of mnemonics: short, verbal devices that encode a long series of facts by associating them with familiar and previously encoded information.

Mnemonics help us encode information in a creative and distinctive way, which makes it much easier to recall. Acronyms and jingles are commonly used mnemonics. AT&T is easier to remember than American Telephone and Telegraph. Marketers devise clever jingles and rhymes to build product recognition and keep that annoying commercial playing in your head long after you’ve changed the channel.

Psychological research has focused on three types of mnemonic strategies: natural language mediators, the method of loci, and visual imagery.

Using natural language mediators involves associating new information with already stored meanings or spellings of words. Creating a story to link items together is an example of using natural language mediators. For instance, to remember the three stages of memory, you might say, “It doesn’t make sense (sensory memory) that she’s working (working memory) so long (long-term memory).”

The method of location could help you remember a grocery list. Imagine a familiar place, like your office or bedroom, and mentally place the items from your list on various objects around the room. When you need to recall them, take a trip around the room and retrieve them.

Visual imagery is a third mnemonic device. In this method, you just create vivid mental pictures of your grocery items. Mentally picturing a cat mixing shampoo and eggs to make cat food would certainly create a lasting impression on your memory.

Mnemonics Boosters

Mnemonic images are not all equally effective. Our brains prefer some cues over others, such as positive over negative images, vivid/colorful over bland/dull, and funny/peculiar over normal. Using all your senses and giving your images movement are added memory enhancers.

INSIGHT

Are you having trouble remembering difficult information? Don’t say it, sing it! Many medical schools teach their students songs with familiar tunes but with new words to help them memorize anatomy, diseases, and so on. Don’t believe me? Ask your doctor to sing the “Supercalifragilistic” song—it probably won’t be the words you learned!

Your memories are under construction. They can change with time, and your past history, current values, and future expectations influence them. In addition, they can be strengthened, or even built, by social influence.

In fact, while our memory is a hard worker, it gets easily confused. Memory studies show that we often construct our memories after the fact and are susceptible to suggestions from others to fill in any gaps. A police officer can cause a victim to err in identifying an assailant just by showing a photograph of the suspect in advance of a lineup. The lineup is now contaminated by the photograph, making it hard to know whether the victim recognizes the suspect from the crime scene or from the photograph.

INSIGHT

Don’t rely on your gut instincts to improve your memory. Research clearly shows that the fact we feel certain about a memory doesn’t necessarily mean it’s accurate.

Sleep: Memory’s Silent Partner

Sleep improves the brain’s ability to remember information. But sleep doesn’t just passively protect memories; it plays an active role in memory consolidation.

Most sleep researchers agree that sleep strengthens procedural or “how-to” memories. There’s still some debate about the degree to which sleep benefits declarative memory, but some new studies suggest that people who sleep between learning and testing are able to recall more of what they learned than those who don’t sleep after learning.

Here’s how new memories are created:

Daily events become short-term memories in the hippocampus and are then transferred to a long-term storage area in the neocortex, which is the gray matter covering the hippocampus. And all this happens while we snooze.

The 90-Minute Power Snooze

And here’s good news! You don’t have to wait till bedtime to consolidate your memory. A 90-minute nap helps speed up learning by consolidating long-term memory faster. Not only can you grab an extra forty winks without guilt, you can make yourself smarter even faster.

A snooze can also prevent interference. When participants in a study learned a new task two hours after practicing the first task, the second task interfered with the memory consolidation process. The learners showed no performance improvement, either that night or the following morning—unless they had taken a 90-minute nap in between the two learning sessions.

Interestingly, the snooze-induced improved performance didn’t show up until the next morning; both nappers and non-nappers showed the same amount of learning interference the evening in which the two tasks were introduced. Apparently, daytime sleep between learning activities shortens the amount of time for procedural memories to become immune to interference.

INSIGHT

Staying mentally and physically active during old age may reduce the risk of Alzheimer’s and other dementias by as much as 46 percent! Even mild learning (e.g., reading, solving math problems, or working crossword puzzles) may reduce both the pathology and cognitive decline of Alzheimer’s. And studies show that older people who exercise three or more times per week have a 30 to 40 percent lower risk of developing dementia. One study found that just 20 minutes of activity each day can prevent memory deterioration and lead to a lasting improvement in overall memory function.

The Truth About False Memories

In 1990, teenager Donna Smith began therapy with Cathy M., a private social worker who specialized in child abuse. Although Donna had entered treatment reporting she had been sexually abused by a neighbor at age 3, Cathy M. repeatedly interrogated Donna about her father. After several months of pressured questioning by her therapist, Donna lied and said her father had touched her. When her therapist reported her father to the authorities, Donna tried to set the record straight, only to be told by her therapist that all abuse victims try to recant their stories.

Donna was confused but continued to work with Cathy M. Over the course of several months, Donna came to believe that her father had been a chronic sexual abuser. She began “remembering” him practicing ritual satanic abuse on her younger brothers. Only after she was placed in foster care away from her therapist did Donna regain her perspective and the courage to tell the truth. By this time, her family was emotionally and financially devastated.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Were you watching television the morning of September 11, 2001? If so, do you remember seeing images of the first plane, and then the second plane, hitting the World Trade Center towers? If you do, you are one of the majority of Americans who have a false memory about this! Only the video of the second plane hitting a tower was shown on that day. The video of the first plane striking the other tower was not shown until the following day—September 12. But, according to a 2003 study in Applied Cognitive Psychology, almost three out of four of us remember it incorrectly.

Sorting the True from the False

Unfortunately, Donna’s experience is not an isolated incident. There are similar stories of adults who enter therapy to resolve some conflict or gain happiness and, with the therapist’s “support,” suddenly start remembering traumatic abuse or incest. As these repressed memories are unleashed, the person may take action such as criminal prosecution or public denouncement.

DEFINITION

A repressed memory is the memory of a traumatic event retained in the unconscious mind, where it is said to affect conscious thoughts, feelings, and behaviors even though there is no conscious memory of the alleged trauma.

While false memories do occur, by no means are most memories of childhood sexual abuse false. Given that many girls are sexually exploited before the age of 18, there is a good chance that someone who remembers being abused as a child is telling the truth. The rare occurrence of false memory is likely to happen when a vulnerable person hooks up with a therapist who, intentionally or not, implants false memories through hypnotic suggestion, by asking leading questions, or by defining abuse and incest so broadly that, in retrospect, innocent actions suddenly take on menacing meaning.

One recent large-scale study sought to corroborate memories of childhood sexual abuse through outside sources. Participants were sorted into three categories of recovered memories:

- Spontaneously recovered: Victim had forgotten but spontaneously recalled the abuse outside of therapy with no prompting

- Recovered in therapy: Victim recovered the memory of abuse during therapy, prompted by suggestion

- Continuous: Victim had always been able to recall the abuse

Overall, spontaneously recovered memories were corroborated about as often (37 percent of the time) as continuous memories (45 percent). Interestingly, memories recovered in therapy could not be corroborated at all. While the absence of corroboration doesn’t imply that a memory is false, this study suggests that memories recovered in therapy should be viewed cautiously. There is a very real fear that a few misguided therapists and their clients could undermine the true stories of thousands of others.

From the Mouths of Babes

When courts instruct a witness to tell the whole truth and nothing but the truth, they’re telling him not to lie. But they’re not allowing for a third possibility: a poor (or false) memory. And they generally assume the memory of adults is more reliable than that of children.

But maybe not.

Studies conducted by Cornell University’s Valerie Reyna and Chuck Brainerd suggest that children may be more reliable court witnesses because they depend more heavily on a part of the mind that records what actually happened, while adults depend more on another part that records the meaning of what happened. Meaning-based memories are largely responsible for false memories—especially in adults, who have far more meaning-based experience than children.

Apparently, people store two types of experience records or memories: verbatim traces and gist traces. Verbatim traces are memories of what actually happened. Gist traces are records of a person’s understanding of what happened or what the event meant to him or her. You can see how gist traces could stimulate phantom recollections or vivid illusions of things that never happened; for example, misremembering that the object in a person’s hand was a gun when it wasn’t. Since witness testimony is the primary evidence in many criminal prosecutions, false memories are a primary reason for convictions of innocent people.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Studies show that emotionally negative events stimulate higher levels of false memory than neutral or positive events; in fact, the likelihood of false memory increases with the degree of aversion a person feels.

I vividly remember the exact moment the Columbia space shuttle exploded on February 1, 2003. My mom could vividly remember where she was and what she was doing when she heard that John F. Kennedy had been assassinated. Nineteenth-century researchers discovered the same phenomenon when they asked people what they were doing when they heard that Abraham Lincoln had been shot.

These memories are called flashbulb memories, long-lasting and deep memories that occur in response to traumatic events. Not everyone has flashbulb memories, and not every tragic situation causes them. Recent research, in fact, has questioned the validity of the flashbulb effect, but what it does support is our tendency to remember upsetting or traumatic events, and, in particular, the emotions we felt at the time.

Memory Under Fire

Memory research shows that, during times of extreme stress or trauma, the hippocampus (the part of our brain that records personal facts) may dysfunction, causing the details of the traumatic event to be poorly stored. On the other hand, the amygdala, that part of our cortex that stores emotional memories, often becomes overactive when under stress, enhancing the emotional memory of a trauma. As a result, a 25-year-old might be terrified of flying because of a traumatic plane ride as a child and yet not remember the childhood experience that triggered the fear. She remembers the emotions of her ride of terror but not the ride itself.

Traumatic memories are tricky. In general, real-life traumas in children and adults—such as school ground shootings or natural disasters—are well remembered; in fact, complete amnesia for these terrifying episodes is virtually nonexistent and some people report having great difficulty getting the events out of their dreams or minds even though they want to.

On the other hand, we also know people forget things. People later remember things they had forgotten earlier. And psychologists generally agree it’s quite common to consciously suppress unpleasant experiences, even sexual abuse, and to spontaneously remember such events long afterward. I’ve had therapy clients who were victims of documented incest (the perpetrator had confessed and been sent to prison), and yet siblings who were also victims claimed to have no memory at all that abuse had ever occurred.

- Our memory doesn’t mind very well—it often misremembers, forgets, and makes mistakes.

- The three mental operations required for memory are encoding (putting information in), storage (filing it away), and retrieval (finding it); forgetting is a failure in one of these areas.

- Mnemonics are very effective memory aids that help us store information in a way that enables us to easily recall it later on. And the use of written reminders and other memory strategies can be especially useful for the elderly, who tend to have more problems remembering recent events.

- Sleep is believed to be actively involved in consolidating memory, especially procedural memories.

- Mental and physical exercise can slow the impact of degenerative neurological diseases, such as Alzheimer’s.

- False memories can fool us and professionals as well; although not likely, it is possible to remember serious childhood trauma that never happened.