What’s Your Motive?

In This Chapter

- The needs that drive human behavior

- The body’s balancing act

- The dieter’s dilemma

- Sex, a state of mind and body

- The thirst for power and the drive to achieve

As a child, Michael Phelps couldn’t sit still, couldn’t focus, couldn’t buckle down. Due to his lack of concentration, his third-grade teacher wondered if he’d ever achieve anything. But on August 18, 2008, he set seven world records and won his eighth Olympic gold medal for swimming the butterfly leg of the 4 × 100-meter medley relay. His former teacher wrote Phelps’s mother, remarking that perhaps Michael had never lacked focus but, rather, a goal worthy of his focus.

Motivation is the psychological force that drives us to do the things we do. But where does motivation come from? How do we work toward our life goals, stick to our diet, study when we feel like sleeping, and keep going when life drags us down?

In this chapter, we explore the motives that drive human behavior, including physiological motives like hunger and sleep and sex. You’ll see why you need them and what you’ll do to get them. We explore the mind-motive connection and the pluses and minuses of having a brain that can influence our base instincts. Finally, we discuss some of the “higher” motives, such as the need for achievement, and give you a chance to find out what motives drive you to work hard every day.

How are you feeling right now? Hungry? Sleepy? Angry? Your mental state will cause you to pay attention to some things over others; if you’re hungry, thoughts of home cooking might get sandwiched in between these appetizing paragraphs. If you’re feeling down, you might have begun this book by reading the chapter on mood disorders. Clearly, your mental state affects your thoughts and your actions.

But what makes you hungry or sleepy or angry, and how do these states influence what we do? When we look at the complexity of human motivation, one thing becomes clear: it isn’t just a jungle out there. It’s a jungle in here, too.

Let’s Get Motivated

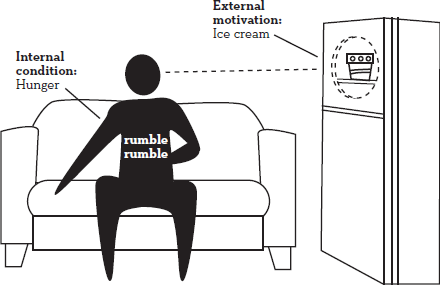

When psychologists use the term motivation, they’re talking about all the factors, inside us and in the world around us, that cause us to behave in a particular way at a particular time. Internal conditions that push us toward a goal are called drives. External motivations are called incentives. Many things, like our genes, our learning histories, our personalities, and our social experiences, all contribute to what drives propel us and what incentives attract us.

Drives and incentives also interact with each other. For instance, if a drive is weak, an incentive must be strong enough to motivate us to act. If the only thing in the fridge is cottage cheese, I’ve got to be pretty darned hungry to walk to the kitchen. Of course, if I’m hungry enough, even cottage cheese can look pretty tasty. So not only can drives and incentives influence one another, they can also influence each other’s strength. I could be full enough that even mint chocolate-chip ice cream wouldn’t be enough of an incentive to get off the couch.

Professors wonder whether students who fail exams aren’t motivated enough. Coaches speculate that winning teams were “hungrier” and more motivated than their opponents. Detectives seek to establish the motive for crimes. Clients come to therapy looking for the motivation to quit bingeing. Not only is motivation one of the most commonly used psychological terms, but it’s also something we never seem to have enough of!

What Drives Your Body?

Our bodies use our drives to keep us alive. For example, body temperature, oxygen, minerals, and water must be kept within a certain range, going neither too high nor too low; this is called homeostasis. When we are out of balance, our bodies push us to take action to regain our equilibrium. For instance, when you chug a quart of water after running a few miles, your drive to drink is motivated by a lack of necessary bodily fluids. When you’re too hot, your body signals you to find cooler temperatures.

Homeostasis is helpful in understanding physiological drives like thirst, hunger, and our need for oxygen, salt, and temperature control. But many things that motivate us aren’t necessary for our immediate survival. Take sex, for example. Most of us are pretty motivated by it, but despite what a manipulative lover may have said, nobody can die from lack of sex.

Psychologists have puzzled over this glitch in the homeostasis theory until their puzzlers were sore. To solve this dilemma, they distinguished between regulatory drives that are necessary for physiological equilibrium, and nonregulatory drives—like sex—that serve some other purpose. However, as you’re about to see, even regulatory drives like hunger can have hidden motives.

The Brain’s Motivation Station

Psychologists must always infer motives from behaviors—after all, we can’t observe motives directly. If you’re drinking (water, at least), others assume you’re thirsty. Psychologists are constantly looking for links between the stimuli (including conditions and situations) that lead to motivation, and the responses (behaviors) produced by motivational states and the brain structures that regulate them.

In the early 1950s, scientists began poking around in the brains of animals to see which parts controlled what drives. They’d either create lesions to remove any stimulation from reaching that part of the brain, or they’d plant electrodes that would provide more stimulation. Then they’d watch to see what happened. What they observed formed the basis of much of what we know today about human drives, particularly hunger.

As it turns out, in the brain circuitry responsible for reward-motivated learning, a mechanism appears to allow events to interact with expectations and motivation to influence what we learn. What happens is this: anticipating a reward activates the reward areas of the brain’s emotion-processing mesolimbic region. This then alerts the learning- and memory-related hippocampus in the medial temporal lobe (MTL), making it more likely we’ll remember the information.

In one study, for example, participants were shown “value” symbols that signified whether the image of the scene that followed would yield 5 dollars or 10 cents if they remembered it the next day. Not surprisingly, subjects were far more likely to remember 5-dollar scenes than dime scenes. Anticipating a reward activated the subjects’ reward areas of the brain’s emotion-processing mesolimbic region, then alerted the learning- and memory-related hippocampus in the medial temporal lobe (MTL).

This suggests that our brain actually prepares in advance to selectively filter rather than simply react to the world. Subjects with greater MTL activation showed better memory performance, suggesting that anticipatory activation of this mesolimbic circuit may help motivate our memory.

The Hunger Center

In the 1950s, scientists discovered the hunger-hypothalamus connection. They found that mice with lesions to the lateral area of the hypothalamus were completely uninterested in food. These animals would literally starve to death if they weren’t force-fed through a tube. On the other hand, if the researchers stimulated the lateral part of the hypothalamus, the mice would gorge themselves. Excited, the researchers quickly proclaimed the lateral hypothalamus as the “hunger center” of the brain.

If you’re looking for a scapegoat to blame those few extra pounds on, don’t jump the gun. Later experiments showed that the hypothalamus was focused on more than food. When researchers presented these same overly stimulated mice with other incentives, such as sexual partners, access to water, or nest-building materials, the animals engaged in behavior that matched whatever incentive was provided. If sexual partners were available, they had an orgy. If water was handy, they drank until they were about to explode! Psychologists now believe that a tract of neurons running through the hypothalamus was responsible for the initial research findings–not the hypothalamus itself.

While stimulation to the lateral part of the hypothalamus causes bingeing, manipulating another part of the hypothalamus, the ventromedial part, has the opposite effect. Stimulation here can cause an animal to stop eating altogether.

We now believe that a tract of neurons running through the hypothalamus was responsible for the initial research findings. This bunch of neurons isn’t actually part of the hypothalamus; they just travel through it on their journey from the brain stem to the basal ganglia. Also as previously noted by the frenzy of activity, this tract seems to be part of a general activation system—stimulation seems to give the message, “You’ve got to do something.” What that “something” is depends upon the available incentives.

We’re All Picky Eaters

When it comes to hunger, the hypothalamus isn’t completely innocent. It has neurons that, at the very least, can modify our appetite. When researchers destroy parts of the lateral hypothalamus, lab animals eat enough to survive but remain at a lower-than-normal weight, and most of their other drives are normal.

To see whether the lateral hypothalamus did indeed play a role in hunger, as opposed to being just a thoroughfare for that tract of hungry neurons, researchers implanted tiny electrodes in this part of a monkey’s brain. What they found is that the hypothalamus is a picky eater.

First of all, the monkey would only become excited by the sight or smell of food if it was hungry and food was available. In addition, the hypothalamus would get “tired” of certain foods; if the monkey had eaten several bananas, the hypothalamus cells would stop responding to bananas but would continue to respond to peanuts and oranges!

What all this means to us is that the hunger motive involves a part of the brain that is programmed to respond to food cues when we’re hungry. When we’re not hungry, those same food cues would leave us disinterested, at least from a physiological perspective. If you’ve ever been on a diet and found yourself drooling over every food commercial, your response is literally all in your head!

PSYCHOBABBLE

Apparently, the beginning of a new year is not enough motivation for most of us to shed extra pounds. At the stroke of midnight every New Year’s Eve, more than 130 million Americans resolve to lose weight but only 14 percent will keep those resolutions.

Now let’s get a few things straight. A person’s weight has little to do with willpower. Studies show that thin people have no more willpower than fat people do. Skinny people are not more conscientious or less anxious. They are not morally superior. In fact, fat people and thin people do not differ on any personality characteristics.

But don’t obese people eat more than people of normal weight? Maybe. Research indicates that while most people of normal weight generally eat only when hungry, most overweight people frequently eat for emotional, rather than physical, reasons. And the same neurochemical imbalance that leads to depression can also tempt us to consume excessive amounts of carbohydrate-rich foods, raising the possibility that some people who chronically overeat may, in fact, be depressed.

Of course, the relationship between food and feelings is complex for many of us. All dieters, regardless of their weight, are more likely to eat in response to stress; the weight difference between stress eaters and non-stress eaters may be that overweight people are more likely to be on a diet. Stress can make all of us vulnerable to the munchies, but if we’ve been fighting hunger cues already, we’re more likely to give in to temptation.

INSIGHT

Want to lose weight? Strike the word diet from your vocabulary forever. Instead, exercise five times a week (for at least 30 minutes); don’t dip below 1,200 calories per day or try to cut fat completely; quit depriving yourself of favorite foods; and get reacquainted with your body’s hunger and fullness cues.

Mmmmmm, It’s So Appetizing!

Another challenge for dieters is our culture’s appetizer effect, which tricks our bodies’ normal methods of food-regulation. Here’s how it works: all of us have built-in signals for hunger and fullness. When we’re hungry, our stomachs growl; when we’re full, our stomachs send signals to the brain telling us to stop eating. The amount of sugar (glucose) in the blood also cues our bodies to start or stop eating; high blood sugar says stop, and low blood sugar says go. And our fat cells secrete a hormone, leptin, at a rate proportional to the amount of fat being stored in our cells. The greater the amount of leptin, the less our hunger drive is stimulated.

The problem is that our environment can have a powerful influence on our hunger. Any stimulus in our environment that reminds us of good food can increase our hunger drive—and that’s where the appetizer effect kicks in. Food commercials, the availability of yummy foods, or the smell of McDonald’s french fries can overwhelm the body’s fullness signals. In addition, the appetizer effect can actually stimulate physical hunger.

PSYCHOBABBLE

The average American consumes 3,800 calories a day, more than twice the daily requirement for most adults.

I’ll Take Just One!

In a fascinating experiment, researchers placed a mixing bowl of M&Ms in a lobby and experimented with various spoon sizes. Indulgers tended to take only a single spoonful of M&Ms, regardless of spoon size or quantity of M&Ms. Since some munchers weren’t aware they were being observed, we can’t attribute this unit bias solely to participants’ concerns that they’d be perceived as gluttonous. It appears that we may have a culturally enforced consumption norm that tells us a single unit is the proper amount to eat.

Unit bias may provide insight into how portion and package size affects consumption, and perhaps, ultimately, obesity. It also argues for eating on smaller plates!

My Genes Made Me Do It!

Just in case you aren’t completely bummed out by now, there’s yet another reason why dieting is so hard. We each inherit a certain weight range, and it’s difficult, without a major life change, to get below it. If your genetic weight range is between 120 and 140, you can comfortably maintain a weight of 120 through a healthy diet and regular exercise. If, however, you wouldn’t be caught dead in a bathing suit until you’re below 110 and are constantly dieting to reach this goal, you’re setting yourself up for failure.

Even if you starve yourself down to this weight, you’ll have a lot of trouble maintaining it because your body will fight to get back to its “natural” weight. And losing and regaining weight, known as yo-yo dieting, tends to make you fatter over time. In fact, while dieting is often promoted as a solution for weight loss, it’s often what causes average-size people to gain weight in the first place!

INSIGHT

Obesity sleuths have found clues to at least 20 of the most chronic and deadly medical disorders (breast cancer, cardiovascular disease, Type II diabetes, and so on) in the conflict between our sedentary lifestyle and our built-in genome for physical activity. Apparently, we inherited our need for exercise from our Paleolithic ancestors; when we don’t engage in regular physical exercise, it can lead to an altered protein expression of this genome that leads to chronic illness.

But that’s enough about food; now let’s talk about sex. Though we said previously it is not necessary for our survival, most of us would agree that sex makes life more enjoyable, and is important to our psychological well-being.

Physically, both men and women go through the following four stages of sexual response:

- Excitement. This is the beginning of arousal. Everything heats up; blood rushes to the pelvis, and sex organs enlarge.

- Plateau. This is the peak of arousal. You breathe faster, your heartbeat speeds up, and you get ready for the climax.

- Orgasm. This is the release of sexual tension. Men ejaculate and women experience genital contractions.

- Resolution. This is the letdown as the body gradually returns to normal.

Driving the Sex Machine

I hate to burst your bubble, but calling someone an “animal” in bed is not a compliment. When it comes to sex, we humans are much wilder and have a lot more fun. A lot of female animals, for example, only have intercourse at certain times of the month, whereas women are liberated from the control of their menstrual cycle. We can, and do, get turned on at any time during the month. And among animals, intercourse occurs in one stereotyped way. For humans, sexual positions are limited only by our imagination.

INSIGHT

If you’re getting ready for a hot date, don’t skimp on the fragrance. A recent study found that a few whiffs of men’s cologne actually increased physiological arousal in women. And another study found that men guessed a woman’s weight as being lower when she wore perfume than when she didn’t!

Those Sexy Hormones!

We do have some things in common with our less sexually evolved friends, however, and one of those things is hormones. In all mammals, including humans, the production of sex hormones speeds up at the onset of puberty. Men get jolted with testosterone and women get an estrogen charge. However, these famous hormones have a silent partner that gives us a head start in the sex department. This helper is produced by our adrenal glands, and is called dehydroepiandrosterone or DHEA.

Before we enter that tumultuous time called puberty, DHEA is already behind the scenes stirring things up. Boys and girls begin to secrete DHEA at about age 6, and the amount rises until the mid-teens, when it stabilizes at adult levels. Most men and women recall their earliest clear feelings of sexual attraction as occurring at about 10 years of age, well before the physical changes brought on by estrogen or testosterone. Research suggests that DHEA brings on these feelings.

PSYCHOBABBLE

New United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention studies show that teens who’ve had formal sex education are far more likely to put off having sex. Boys were 71 percent less likely to have intercourse before age 15; girls 59 percent less likely. And boys were three times more likely to use birth control the first time they did have intercourse.

Tanking Up on Testosterone

Once things do get stirred up, though, testosterone keeps men and women going. Testosterone maintains a man’s sexual drive during adulthood by stimulating his desire. Men with unusually low levels of testosterone show a dramatic increase in sex after a few booster shots. However, a couple of extra testosterone doses won’t turn a man into a sex maniac; if his testosterone is within normal limits, any additional amount doesn’t seem to have any effect.

In women, ovarian hormones, like estrogen, play a role in our sex drive. Our adrenal glands also play a role: they produce DHEA and, believe it or not, testosterone. As with men, testosterone treatment can give a low libido a much-needed jolt; while it hasn’t yet received FDA approval, a testosterone patch has been developed to reverse sexual apathy.

However, let’s not forget that, for women, much of our sexual desire is based on interpersonal and contextual—not physical—factors. If we’re trying to restore our sexual flames, improving the intimacy in our romantic relationships, having plenty of time and energy to give, and eliminating stressors like the fear of getting pregnant may be much more effective (and less expensive) than a trip to the doctor’s office.

The complexity of human sexuality is wonderful, but the rewards have their risks. Because human sexuality is as influenced by the mind as it is by the body, physical and psychological factors can throw one’s sex drive out of gear. Traumatic sexual experiences, fears of pregnancy or disease, relationship conflicts, performance pressure, and shameful messages about sexuality can reduce sexual desire and can even prevent your body from functioning normally. Physical causes of sexual difficulties include various drugs, medications, and chronic medical conditions. The causes of sexual difficulties are as varied and unique as the problems that result from them.

When a person has ongoing sexual problems, he or she may have a sexual dysfunction—a frequently occurring impairment during any stage of the sexual response cycle that prevents satisfaction from sexual activity. These disorders generally fall into four categories: sexual desire disorders, sexual arousal disorders, orgasm disorders, and sexual pain disorders. The two most widely publicized disorders have been sexual arousal disorder in women and impotence (erectile dysfunction) in men.

Dealing with Dysfunction

The most effective treatment, of course, depends upon the nature of the sexual dysfunction. Some sexual dysfunctions, like a chronic lack of desire, tend to be psychological in nature, while others, such as sexual pain disorder and erectile dysfunction, can have numerous causes. In many situations, a combination of physical and psychological treatments is most effective.

INSIGHT

While the most common sexual dysfunction in men is premature ejaculation, half of all men experience occasional impotence, and for one out of eight men, it’s a chronic problem that tends to increase with age. While drugs for erectile dysfunction (like Viagra and others) can be helpful if the cause is purely physical or related to confidence alone, the drugs can’t heal relationship problems or underlying psychological issues.

The Fragile Sex

Sexual dysfunction can, however, result from many factors, including demographics, culture, lifetime experiences, and changing mental and physical health.

As we age, women may be more likely than men to experience sexual dysfunction due to physical health issues. In older women, physical problems such as urinary tract syndrome or pain from lack of lubrication commonly decrease sexual interest. Among men, mental health issues and relationship problems contribute both to a lack of sexual interest and the inability to achieve orgasm, while urinary tract problems can cause erectile dysfunction.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Here’s another plug for safe sex. A history of sexually transmitted disease can affect sexual health later in life. According to a National Institutes of Health study of people ages 57 to 85, having had an STD quadruples a woman’s odds of reporting sexual pain and triples her lubrication problems. Men who have had an STD are more than five times as likely to report sex as nonpleasurable.

Oriented Toward Sex

Clearly, human sexuality is pretty complicated. Even your most primitive sexual urges are often at the whim of your thoughts and feelings. And while these thoughts and feelings can certainly add spark to your sex life, they can also dampen your ardor. Your sex drive can go up or down depending on a lot of physical and psychological factors.

The causes of sexual orientation have been a matter of political debate and scientific inquiry. In fact, so many theories have been thrown around, so many political agendas mixed in with science, and so much misinformation distributed that it’s hard to tease out truth from fiction. Psychologists haven’t exactly been at the forefront of the tolerance movement; in the 1980s, homosexuality was still classified as a mental disorder.

In the past, most psychologists argued that sexual orientation was learned. Some still do. However, there are a few problems with this explanation.

PSYCHOBABBLE

A 10-year APA study suggests that bisexuality in women appears to be a distinctive sexual orientation, not an experimental or transitional stage on the way to lesbianism. The study also debunks the stereotype that bisexual women can’t commit to long-term relationships (1+ years). By year 10, a large majority were involved in long-term, monogamous relationships.

First, if sexual orientation is learned, why is it that the majority of children raised by two homosexual parents are heterosexual? Why does homosexuality exist in other species? And why are the statistics of homosexual men and women, between 1 and 5 percent, the same in countries where homosexuality is accepted and in countries where it’s outlawed?

Scientists trying to determine biological differences between gay and straight men have found that sniffing a chemical from testosterone, the male sex hormone, causes a response in the sexual area of both gay men’s and straight women’s brains—not, however, in the brains of straight men. Scientists have also located a gene in fruit flies that, when altered, completely changes the sexual orientation of the insect. While all the evidence isn’t in, the pendulum seems to be swinging toward a biological basis for sexual orientation.

INSIGHT

Our sexual orientation is an enduring emotional, romantic, sexual, or affectional attraction toward a certain gender (or genders). Having fantasies about, or even one or two sexual encounters with, your same gender does not necessarily mean a person is homosexual. In 2005, the Centers for Disease Control released a survey showing that 11.5 percent of “straight” women and 6 percent of “straight” men had experimented in gay sex at least once.

It’s Just the Way It Is

We know genetic differences play some role in determining sexual orientation. Roughly 50 percent of identical twins share the same sexual orientation. If you have a gay sibling, your chances of also being gay are about 15 percent, compared to 1 to 5 percent of the general population.

Recent studies suggest that sexual orientation is something we discover about ourselves, not something we choose. Homosexuals and heterosexuals alike say their sexual orientation was present in their childhood thoughts and fantasies, typically by age 10 or 11. This probably jibes with your own experience. In fact, odds are, at some point you just knew your sexual orientation, probably long before you understood it. Whatever its cause or causes, sexual orientation is a deeply rooted and early emerging aspect of our self.

PSYCHOBABBLE

It seems our politics are catching up with our research. As of 2013, 21 states and the District of Columbia have laws that prohibit discrimination because of a person’s sexual orientation, and bills to add this demographic to the federal civil rights laws are regularly cropping up in our nation’s capital.

In Search of Higher Ground

Sex is a lot of fun, but we can’t spend all our time doing it. In fact, in the late 1960s, Abraham Maslow proposed the revolutionary idea that people are ultimately motivated to grow and reach their potential. At a time when most psychologists thought motivation was driven by a need to make up for some physical or psychological deficit, Maslow’s optimistic view of human motivation was a breath of fresh air.

Moving on Up

Maslow would certainly agree that we have to put first things first—basic needs have to be met before we search for a higher purpose. If we’re starving, worries about our self-esteem take a back seat. That fight you had with your best friend pales in comparison to the rumblies in your tummy. In wartime and other times of starvation, people have been known to kill family members or sell children for food.

It’s hard to even think about anything else when our basic hunger drive is not being met. Missionaries around the world often feed and clothe people before they try to convert them. They understand that the need for knowledge and understanding is not a priority until we’re fed and clothed.

However, once our basic biological needs are met, the next rung up the ladder is our need for safety and security. In the middle of the hierarchy are our needs for knowledge and a sense of belonging, and at the very top are the spiritual needs that enable us to identify with all humankind.

Of course, not all of us get to the top of the ladder before our time on Earth runs out. However, if you were raised in the ambitious United States, chances are you got far enough up to reach a need for achievement. Let’s take a look at a motive that, for better or worse, has made our country what it is today.

BRAIN BUSTER

Believe it or not, it’s possible to be too motivated. While motivation energizes us for simple tasks, it can quickly disrupt our performance on difficult or more complex ones because the high need to achieve gets consumed by pressure-induced anxiety. A highly motivated (and, of course, prepared) student may be better off exercising for an hour before a test than cramming up to the last minute.

The Need to Achieve

If you had to predict who would be a success in life, would you pick the person with the highest I.Q. score, the best grades, or the strongest need to achieve? Personally, I’d pick the person motivated to do well. We all know bright people who chronically underachieve. And we also know some high school graduates who tanked on their SATs and could now afford to buy the company that publishes them. In the long run, desire and perseverance exceeds talent or brains.

The “need for achievement,” first identified by Harvard psychologist David Murray, refers to differences between individuals in their drive to meet a variety of goals. When your need for achievement is high, you’re energized and focused toward success and motivated to continually evaluate and improve your performance. When channeled properly, this can be an organizing force in linking your thoughts, feelings, and actions. Taken to an extreme, it can be a monkey on your back. Perfectionism is a need for achievement that has gone haywire.

One of the most interesting ways your need for achievement influences you is in the way you approach a challenge. For high achievers, knowing a task is difficult can be a motivator to keep on going. Low-need achievers, however, tend to persist only when they believe the task is easy. Low-need achievers who were told a task was difficult either didn’t think it was worth the effort or weren’t willing to spend it.

What Motive Works for You?

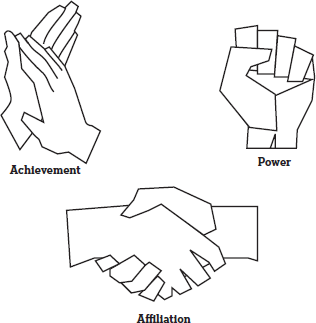

All of us work better when our jobs match our personal motivation. Psychologists David McClellan and John Atkinson found three motives that drive people in work situations, and found that a person’s behavior is likely determined by the degree to which each is present. These three motives are a need to achieve, a need for power, and a need for affiliation.

INSIGHT

Visualizing yourself performing successfully can be a great motivator. Studies show that imagining yourself performing well through the eyes of others (third-person perspective) seems to add more meaning to the task. So the next time you’re rehearsing for that play, ballgame, or killer exam, see yourself through your audience’s eyes.

Will your motives steer you into politics, business, or nonprofit work? Let’s look at each of these three needs in action.

Achievement. At work, you appreciate a supervisor who gets down to business and lets you work independently. You hate for people to waste your time and prefer to focus on the “bottom line” of what you need to do. When you daydream, you are most likely to think about how to do a better job, how to advance your career, or how you can overcome the obstacles you are facing. You can motivate yourself well and like to succeed in situations that require outstanding performance.

BRAIN BUSTER

Children who enjoyed reading were given gold stars as an added incentive, and the experiment backfired! Being handed external rewards for doing something we genuinely like shifts the motivation outside of ourselves; instead, reinforce the internal rewards by asking the child to tell you about the stories he or she reads, read together, or join a parent/child book club.

Power. You have a thirst for power and want a supervisor who’s a mover and shaker and can serve as a role model. You are good at office politics and know that the best way to get to the top is by who you know and who they know. You have strong feelings about status and prestige and are good at influencing others and getting them to change their minds or behavior. When you daydream, you are most likely to think about how you can use your influence to win arguments or improve your status or authority. You like public speaking and negotiating.

Affiliation. You’re a team player, a people person. You want a supervisor who is also your friend and who values who you are and what you do. You are excellent at establishing rapport with others and enjoy assignments that allow you to work within a group. You are very loyal and get many of your social needs met in your job. You are well-liked, great at planning company social functions, and people come to you with their problems and value your advice.

Human motives are fascinating, ranging from basic, universal needs for shelter, food, and clothing to complex, unique drives for self-esteem and achievement. Richard Nixon and Mother Theresa may have both needed to eat, but their “higher” motives led them down vastly different career paths. Whether you’re a born Richard Nixon or Mother Theresa, though, one motivator lights a fire under all of us. In the next chapter, we take a look at the motivational power of emotions.

INSIGHT

Culture affects our motivation, too. In the United States, managers seem to believe that work itself is not intrinsically motivating and so tend to motivate their workers through incentives (bonuses, paid time off, etc.). In China, managers focus on the culturally instilled values of moral obligation and the need to work together for the common good. And the anchor of the Japanese work ethic is trust.

- Our bodies seek to maintain homeostasis or balance—if our equilibrium is off, our body signals us to take action to fix it.

- The hunger drive is a strong part of our body’s balancing act, but not all hunger is based on bodily needs. Strong food cues from the environment can cause physical hunger even if we don’t need food.

- Human beings are the sexiest creatures on the planet, with a wider sexual repertoire and an ability to respond to a number of physical and psychological stimuli.

- Sexual orientation is much more a discovery about oneself than a conscious choice; determined early, it is very rarely changed. However, our sexuality can be disrupted by a number of factors, including our culture, lifetime experiences, and changing mental and physical health.

- Until we meet our basic survival needs, it’s hard to be concerned with love, self-improvement, or spirituality.

- At work, people may be motivated by a need for power, achievement, or affiliation, or a combination of the three.