He’s Got … Personality!

In This Chapter

- Unlocking the secrets of personality

- Explore why Minnesota is the personality state

- Discover the state your traits are in

- Smoothing out the sharp edges of the psyche

- Spotting the “sick” personality

Like many nurses in the early 1900s, Margaret Sanger watched countless women, desperate to avoid having yet another mouth to feed, die from illegal abortions. Unlike other nurses, she decided to do something about it. For 40 years, Sanger challenged the laws that made contraception a criminal act, insisting that women take control of, and responsibility for, their sexuality and childbearing.

She made a ton of sacrifices. She left nursing and put her husband and children in the background—and ultimately changed women’s lives forever. She eventually lost her husband and was jailed several times for illegally distributing information about birth control. But she won! In 1960, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved “the pill,” a contraceptive that Sanger co-sponsored.

In this chapter, you discover what made Sanger the person she was—and what makes you the person you are. We explore all the factors that are involved in developing the personality and establish how much depends upon genes, hormones, environment, or birth order. You’ll learn how psychologists test personalities, how stable our personalities really are, and what the difference is between an offbeat personality and a serious personality disorder.

Finding the Person in Personality

Personality psychologists try to determine how individuals differ from each other yet stay the same within themselves. They tend to focus on two qualities: uniqueness and consistency. But it is important to look at all our unique characteristics, and the settings in which they occur, in order to understand personality.

DEFINITION

Personality is the sum of all the unique psychological qualities that influence an individual’s behavior across situations and time.

For example, someone with a shy personality may blush easily, avoid parties, and wait for other people to take the initiative in conversation. On the other hand, a person who is reticent about public speaking but is outgoing in other social situations wouldn’t be classified as having a shy personality.

Understanding personality traits gives us a sense of who we are and, to some degree, helps us predict the behavior of the people around us. And through personality testing psychologists develop a clearer understanding of our psyches.

A Picture of the Psyche

Personality tests don’t measure how much personality we have but rather what kind. There are two kinds of personality tests: objective and projective. Most objective personality tests are paper-and-pencil, “self-report” questionnaires. You answer questions about your thoughts, feelings, and actions by checking true if the statement is generally or mostly true and false if it is false most of the time. Projective tests, including the well-known inkblots, are pictures of ambiguous stimuli that you interpret.

PSYCHOBABBLE

People who score as extroverts on personality questionnaires choose to live and work with more people, prefer a wider range of sexual activities, and talk more in group meetings, when compared to introverted personalities.

Personality testing scares many people because they misunderstand what it can and can’t do. First of all, personality testing is like taking an x-ray of our psyche: the results can suggest what’s wrong, but they can’t tell us how it got broken or to what extent it’s affecting our lives.

Second, personality test results are not very useful unless they take into account the test participant’s current life situation. Someone who is usually reticent may be unusually enthusiastic if she’s just won the lottery. And a person who’s just lost a loved one might seem gloomy on a personality test when, in fact, he’s just experiencing normal grief.

Minnesota, the Personality State

The most popular objective personality test was developed at the University of Minnesota. The Minnesota Multiphasic Personality Inventory, or MMPI, which first appeared in the 1940s, originally consisted of more than 500 true-and-false questions that asked about a person’s mood, physical symptoms, current functioning, and a whole lot more. In the late 1980s, the original version underwent a significant revision (MMPI-2) because some questions were deemed inappropriate, politically insensitive, or outdated.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Psychologists are getting harder to fool. An up-and-coming personality inventory can predict who is most likely to succeed, even when the subject attempts to exaggerate his skills and abilities. Studies conducted in the workplace suggest that using this bias-resistant test instead of current personality assessments could result in a potential productivity gain of 23 percent per employee.

The MMPI-2 has 10 clinical scales, each designed to tell the difference between a special clinical group (like people suffering from major depression) and a group without any psychological disorder. These scales measure problems like paranoia, schizophrenia, depression, and antisocial personality traits. The greater the difference between the normal group and the person’s scores, the more likely it is that he or she has some characteristics of a psychological disorder similar to the clinical group.

The MMPI-2 also has 15 content scales that measure various mental health problems that aren’t, in and of themselves, diagnosable psychiatric disorders. Some of these content scales measure low self-esteem, anger, family problems, and workaholism, among other problems. The job of these scales is to pinpoint specific problems that either contribute to, or put someone at risk for, a full-blown psychological disorder.

Can You Fool Your Psychologist?

Since objective tests like the MMPI-2 are self-reporting, you might think they’d be easy to fake if, for example, you were faced with the choice of either going to jail or appearing to be crazy so you could stay out of it.

Not really. The MMPI-2 has built-in lie detectors, safeguards that detect carelessness, defensiveness, and evasiveness. So while you’re free to answer “true” or “false” as you wish, it’s almost impossible to convince the test you’re answering honestly if you’re not.

It’d be even harder to fake a projective test like the Rorschach because there are thousands of possible answers. And even if you tried to second-guess the test, the answers you gave would still provide valuable clues about your true personality.

INSIGHT

Projective personality tests are based on the theory that our inner feelings, motives, and conflicts color our perception of the world and, the less structured our environment, the more likely our psyche will spill over onto what we see.

Personalities Are Like Fine Wine

While we think of our personalities as fixed, they do change over time. Researchers found that when the noisiest, most rambunctious children hit their 20s, they were still more boisterous than their peers, yet they had become considerably more laid back in comparison to their earlier years. Perhaps negative feedback from peers over the years made them more self-conscious and quiet or maybe they’d just mellowed with age.

Even if kids start out a certain way, experience and learning can round their sharp edges. Impulsive, insensitive kids can be taught to rein in their emotions and be more considerate to others. And timid, quiet children can work at being more outwardly sociable, even if they’re still introverts on the inside.

INSIGHT

Different personality traits help us at different ages. Openness to new situations predicts intelligence earlier in life, but disagreeableness predicts intelligence later in life (perhaps because we have to work harder to challenge the status quo).

In some respects, we’re all personality theorists. We naturally assume that certain personality characteristics (trustworthiness, for example) will lead to certain behaviors (telling the truth), and we try to associate with people who will do things that make us happy.

Through observations, interviews, biographical information, and life events, personality theory researchers strive to understand personalities and to predict what people will do based upon what they know about them. The tricky part is separating the traits from the states; in other words, figuring out if a person acts in a certain way because of who he is or as a result of what has happened to him.

DEFINITION

A trait is a stable characteristic that influences your thoughts, feelings, and behavior.

A state is a temporary emotional condition.

What State Are Your Traits In?

A personality trait is a consistent tendency to act in a certain way. Generosity, shyness, and aggressiveness are all examples of traits. They are considered integral parts of the person, not the environment.

That’s not to say that the situation doesn’t influence our expression of the traits we have. If someone runs into your car in a parking lot, you’re more likely to fight or yell if you’re a hothead than is someone who’s more laid back. For an emotional firecracker, the environment provides the spark that sets him or her on fire.

Mental states make personality assessment even harder. If someone comes to therapy complaining of depression, a psychologist has to figure out whether that person is in a state of sadness or has a gloomy personality trait.

Psychologist Walter Mischel thinks there may be a “happy medium” between states and traits. He calls these situation-specific dispositions. These are behaviors that are highly consistent over time in response to the same situation but may not generalize across settings. For example, if you were shy in high school, chances are you’ll be shy in graduate school. This doesn’t necessarily mean, though, that you’d be shy with your spouse; perhaps you’re just consistently shy in new situations.

INSIGHT

Children with extreme personalities marked by aggressiveness, mood swings, a sense of alienation, and a high need for excitement may be at greater risk for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder and/or conduct disorder, a new study shows. Kids with both disorders (an estimated 15–35 percent) are at much higher risk of academic failure, criminal activity, substance abuse, and depression.

Allport’s Search for Personality

Psychologist Gordon Allport thought personality traits were the building blocks of an individual’s overall personality. He thought some traits were big building blocks, some were medium-size, and some were smaller. These three different-size blocks represented the varying degrees of influence the trait had on a person’s life.

According to Allport, a cardinal trait is a prominent trait around which someone organizes his life. Martin Luther King Jr. for example, may have organized his life around social consciousness, seeking to improve the quality of life for all people. Not everyone has a cardinal trait.

A central trait represents a major characteristic of a person, such as honesty or optimism; some of us have more than one. Gloria Steinem’s outspokenness, for instance, is a central trait that has enabled her to withstand criticism and controversy and speak before large audiences about women’s rights.

A secondary trait is an enduring personality trait, but it doesn’t explain general behavioral patterns. Preferences and dislikes that are only obvious in certain circumstances are examples of secondary traits. Always getting impatient while waiting in line, or consistently getting the jitters before speaking before an audience, are examples of secondary traits.

Apparently, patience was a central (if not cardinal) trait in Gordon Allport’s personality; he spent his entire career boiling down all of the dictionary’s personality-related adjectives into 200 clusters of synonyms (groupings like easygoing, lighthearted, and carefree). He then formed two-ended trait dimensions. For example, on one such dimension, “responsible” might be at one end, and “irresponsible” would be at the other. All of us fall somewhere on the continuum between these two adjectives.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Personality does count in the love department. People who exhibit positive traits, such as honesty and helpfulness, are perceived as better looking than those who exhibit negative traits, such as unfairness and rudeness. And our perception of people’s physical attractiveness can change over time, depending on whether their personality is endearing or annoying.

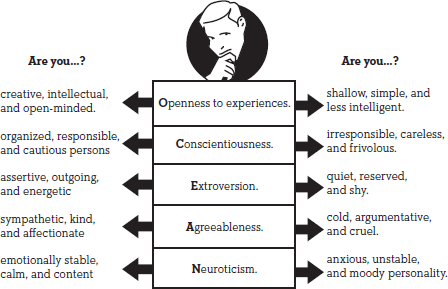

After having countless people rate themselves on these 200 dimensions, Allport found there were only five basic characteristics underlying all the adjectives people used to describe themselves. These became known as the “Big Five” dimensions of human personality—the five categories into which Allport organized all our traits and behaviors. It’s easy to remember them by the acronym OCEAN:

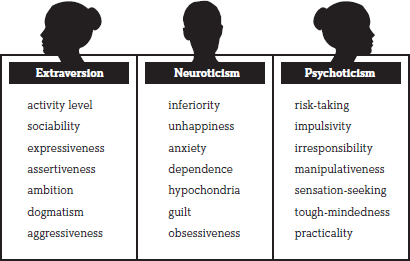

Another psychologist, Hans Eysenck of the University of London, came to believe there were 21 personality traits that were consistent with three major dimensions of personality: extraversion, neuroticism, and psychoticism. In Eysenck’s view, the more of these listed traits you have in each dimension, the higher you score.

Each personality theory we’ve discussed so far emphasizes the ability to get along with others, general emotional adjustment, and flexibility and open-mindedness as key parts of an adaptive personality. But how do people become more open-minded or outgoing? Are we born with pizzazz, or do we have to go to charm school to get it?

The Personalities Behind the Theories

Before you buy into someone’s analysis of your psyche, it’s important to understand the context in which the theory behind it was developed. Each theory of personality was developed in a social environment that influenced the theorist’s thinking. So when you read about the latest or greatest personality theory, pay particularly close attention to the following:

- Whether the theory focuses on normal or abnormal traits, or both

- How much scientific method versus clinical intuition went into the formation of the theory

- Whether the theory explains how personality develops or focuses on adult personalities

Also look for the assumptions behind the theory. Does the theorist think our behavior is more influenced by past events or future goals and aspirations? Does she think our personalities can grow and change, or that we’re stuck with the personalities we’re born with? Neither side of these questions is necessarily right or wrong, but they influence how we view human nature.

Those Temperamental Genes

If you were voted “Best Personality” in high school, is your child destined for popularity? Maybe. There does seem to be a biological part of personalities but a lot of things influence how they take shape.

Well, you can’t blame a people-pleasing personality on a “dependency” gene; on the other hand, you can take full credit for developing your conscientiousness and extroversion. While there are biological parts of our personalities, we have some control over how they take shape.

Our genes provide some of the raw material, e.g., temperament that makes it easier for certain personality traits to blossom. A baby with an easy temperament may develop an optimistic outlook, while an irritable infant may grow into an emotionally expressive child. These temperamental genes appear to interact in very complicated ways, though; in fact, any one gene is likely to account for only 1 or 2 percent of the variability in any given personality trait.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Identical twins share about 50 percent of the same personality traits, the same percentage that they share when it comes to measuring intelligence. And identical twins reared apart are more similar in personality than are siblings or fraternal twins who are raised together. In fact, siblings who are raised in the same family are just about as different as any two people picked at random.

Since the 1950s, researchers have found that newborns and infants vary widely in the following nine temperaments:

Activity level. The amount of physical motion exhibited during the day.

Persistence. The extent to which a baby continues his or her behavior without interruption.

Distractibility. How easily the child is interrupted by sound, light, or other unrelated behavior.

Initial Reaction. How a baby responds to novel situations, i.e., whether she usually approaches or withdraws.

Adaptability. How easily a baby changes his or her behavior in a socially desirable direction.

Mood. The quality of emotional expression, positive or negative.

Intensity. The amount of energy a baby exhibits when expressing emotions.

Sensitivity. The degree to which an infant reacts to light, sound, and so on.

Regularity. The extent to which patterns of eating, sleeping, elimination, and so on, are consistent or inconsistent from day-to-day.

These temperament characteristics have an effect on how we experience our upbringing and may lead us to choose very different friends, activities, and life experiences. With all these variables, maybe no two people ever grow up in the “same” family!

INSIGHT

We know our states can change like the wind, but how about our basic personality traits? New research suggests that, despite the fact that we are born with a certain set of predispositions that lead us in specific directions, we also have the capacity to change throughout our lives. Over time, many of our less desirable traits seem to fade quite naturally, with more pleasing and social parts of our personality coming forward.

Personality by Birth Order

Numerous studies suggest that we’re likely to share some of the same personality traits with people who share the same birth order, perhaps because we share similar experiences. As a general rule, because firstborns are older, they’re first to receive privileges and the first to be asked to take care of younger siblings. The firstborns’ position makes them special and, at times, burdens them. For example, they tend to be leaders, but they also may be hard to get along with and are most likely to feel insecure and jealous.

Middle children tend to be diplomats, while the babies in the family are the rebels. Having been picked on and dominated by firstborns, later children are more likely to be open to new ideas and experiences and support innovative ideas in science and politics. Later-born children are also more agreeable and more sociable—firstborns may be most likely to achieve, but later-borns are clearly most popular. There are always exceptions to these birth order commonalities, but it does seem that the order in which we enter the family pushes us to develop certain personality traits.

INSIGHT

Do you think all the birth order stuff is nonsense? Mention it to the next PhD you meet. About 90 percent of people with doctorates—not to mention the vast majority of U.S. presidents—are first-borns or only children!

The uniqueness of our own personalities far outweigh any personality differences based on gender. The most consistent gender-based difference across countries so far is that women are easier to get along with. About 84 percent of women score higher on measures of the ability to get along with others than the average man.

But it’s not all bad news for men. Men still tend to earn more. Social equality issues aside, men seem to develop personality traits that encourage risk-taking, and in general, risk-taking jobs often pay more.

INSIGHT

Our culture shapes the development of our personality by encouraging differing parenting strategies, communicating certain values, reinforcing certain behaviors, and teaching social rituals. In fact, some researchers think that various cultures have a national character that permeates social interactions and results in the tendency for certain personality characteristics to develop in members of that culture. For example, although no definitive culture traits define all Americans, expatriates who’ve survived the culture shock of living in the United States consistently describe us as friendly, open with personal information, insular, fast-paced, assertive, and noisy.

Disturbing Personalities

So far, we’ve spent our time talking about normal personalities and how we get them. But how does an abnormal personality develop? And when does an eccentric personality become a personality disorder?

We’re All a Little Bit “Off”

Personality disorders are chronic mental disorders that affect a person’s ability to function in everyday activities. While most people can live pretty normally with mildly self-defeating personality traits (to some extent, we all do), a person with a true personality disorder can’t seem to adjust his behavior no matter how much it interferes with his daily life. And, during times of increased stress the symptoms of a personality disorder are likely to ramp up and seriously interfere with their ability to cope effectively.

DEFINITION

A personality disorder is a long-standing, inflexible, and maladaptive pattern of thinking, perceiving, or behaving that usually causes serious problems in the person’s social or work environment.

But It’s All About Me and My Needs!

For example, we all know someone who hogs the limelight or seems to constantly seek approval or recognition. But although we might not like such people or find them pleasant to be around, their self-centered personality traits don’t necessarily indicate a narcissistic personality disorder.

A person with narcissistic personality disorder, on the other hand, has a grandiose sense of self-importance, a preoccupation with fantasies of success or power, and a constant need for attention and admiration. He might “overreact” to the mildest criticism, defeat, or rejection. In addition, he’s likely to have an unrealistic sense of entitlement and a limited ability to empathize with others. This lack of empathy, tendency to exploit others, and lack of insight almost always results in serious relationship problems. This is not a person who is merely selfish; he genuinely can’t relate to others.

Keep in mind that true personality disorders are usually severe enough to interfere with a person’s life in some way. A hunger for the limelight can be healthy if it’s channeled in the right direction; without it, many of our greatest actors might not have chosen acting as a profession.

INSIGHT

Psychological disorders are often classified as either ego-dystonic or ego-syntonic. Behaviors, thoughts, or feelings that upset you and make you uncomfortable are ego-dystonic; you don’t like them, you don’t want them, and you’re motivated to get rid of them. But personality disorders are often ego-syntonic. That means you can have what everyone else considers a disorder—they don’t like it, and you make them uncomfortable—but as far as you’re concerned, it’s everyone else’s problem, not yours.

How Personality Disorders Develop

Mental-health professionals disagree about the prevalence and makeup of personality disorders. But a few things are generally accepted as true on the subject.

The seeds of a personality disorder may be recognizable in childhood and adolescence, but is never formally identified until a person reaches late adolescence or early adulthood. In fact, a child cannot be diagnosed with a personality disorder because his or her personality is still being shaped. When a personality disorder does exist, it is likely to be the result of a combination of parental upbringing, one’s innate personality, and social development, as well as genetic and biological factors.

The Best Treatments for Personality Disorders

Personality disorders can be difficult and time-consuming to treat but are not impossible. The treatment of choice is structured psychotherapy actively focused on reducing self-defeating behaviors, improving interpersonal relationships, and teaching the client to handle difficult emotions (for example, by learning to mentally observe one’s feelings rather than getting overwhelmed by them).

Medications for personality disorders are usually aimed at alleviating symptoms associated with the disorder, such as the impulsivity and unstable moods associated with borderline personality disorder, rather than the disorder itself. Popular antidepressants include the SSRI category (serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitors) like Prozac, Paxil, Effexor, or Abilify.

As you’ve seen, personalities are complex, shaped by both genetics and the environment, and, to some extent, can change over time. While this makes it difficult to predict someone’s behavior, personality tests are one tool that can help us understand how traits lead to behavioral patterns. In the next chapter, you’ll learn about the methods people use to protect their personalities and defend themselves emotionally.

PSYCHOBABBLE

New research suggests that the main benefit of treatment of personality disorders may be to speed up a recovery process that occurs naturally as we age. About 90 percent of clients diagnosed with borderline personality disorder in their 20s no longer meet the criteria by midlife—even without treatment.

The Least You Need to Know

- Your personality is a complex assortment of unique traits that are stable over time and across settings.

- Psychologists use both objective and projective personality tests to figure out who we are and sometimes (but not always) predict what we will do.

- We all have traits, characteristics of personality that are relatively stable and consistent over time, and we all have states, temporary emotional responses to specific situations.

- A number of things, including genetics, environment, culture, birth order, and gender, influence personality development.

- Personality disorders are chronic mental disorders that affect a person’s ability to function in everyday activities; they are complex, somewhat fuzzy, and difficult—but not impossible—to treat.