Conform to the Norm

In This Chapter

- Discover what a bad situation can make you do

- Find out how far we’ll follow the leader

- The three R’s of social psychology

- Get help when you need it

- Some attributes we all share

- Meet the spin-doctor within

How would you feel if you had to go to prison? Would being an inmate change you? Or could you rise above the circumstances? Phillip Zimbardo’s Stanford Prison Experiment suggests the answer may surprise you.

Here’s what went down. Law-abiding, emotionally stable, and physically healthy college students were randomly assigned the role of either inmate or guard to live in a simulated prison for 14 days. In a surprisingly short time, students in the role of prison guard began behaving aggressively, sometimes even sadistically. The “prisoners” also changed dramatically, becoming passive and compliant in response to their new fate. In other words, the pretend prison quickly became a real prison in the minds of jailers and captives alike, so much so that some prisoners had to be released early due to their extreme stress reactions. What was supposed to be a two-week experiment was terminated after only six days!

Welcome to the study of social psychology, which investigates how people are influenced by their interactions and relationships with others. In this chapter, we take a look at how social settings influence how we think, feel, and act, and how we look to others for cues to guide our own behavior, often without realizing it.

Most of us believe we’re the captain of our ship, charting the course of our lives with perhaps minor input from our shipmates. We tend to view situations as strong winds; sure, they may blow our sails around a little, but we can just batten down the hatches and tough it out.

Social psychologists don’t buy that. They understand that each person has a unique personality, core beliefs, and values. But they also believe that social situations can dominate our thinking and behavior regardless of our values or beliefs. And the mere presence of others can powerfully—even unconsciously—influence our behavior. Let’s take a look at three ways a situation wields power over us—roles, rules, and norms.

Learn Your Roles

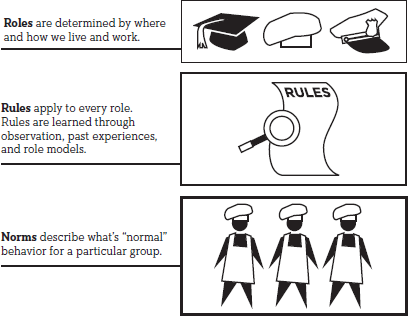

The roles available to us are determined by where and how we live and work. Being an engineer, for example, reduces the chances that we will become a mercenary, a priest, or a drug pusher. It does increase the odds we’ll become a member of some technical association.

Of course, most of us play many different social roles every day—wife, mother, executive, friend. These roles can be refreshing and energizing if they allow us to express complementary parts of ourselves, or confusing and upsetting if they call for conflicting behaviors. For example, imagine being the top executive at a company where your job is to boss people around all day. At six o’clock, you come home and are immediately expected to be warm and nurturing. This can cause role strain, not to mention a few extra gray hairs.

There are rules for every role. We learn them through observation, past experiences, and role models. In fact, pretty quickly we learn to size up a situation and adjust our behavior accordingly—or pay the consequences. And the “right” behaviors in one role may be all wrong in another role.

Adapt to the Norms

Groups also develop social guidelines for how their members should act. When social psychologists use the term “norm,” they’re talking about what’s “normal” behavior for a particular group. We also have these in our relationships; every time we adjust our behavior to get along with someone, we’re adapting to his norms.

INSIGHT

What’s normal isn’t always what’s healthy. A startling one fourth of United States women suffer domestic violence in their lifetimes, leading to ongoing, long-term health problems that the CDC (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention) likens to “living in a war zone.” For women who grow up with abusive parents, a battering relationship can seem normal.

Social norms can dictate what to wear, how to speak and certain standards of conduct. For example, the machismo of high-contact sports such as football and wrestling may actually fuel aggressive and violent behavior among males, both on and off the field or mat. Research shows that the risk of getting involved in fights increases dramatically for high contact sports players who hang out primarily with their teammates.

Norms aren’t all bad, though. They can provide comfort and a clear sense of knowing what to expect from others and how to gain acceptance and approval. Norms provide us with the first steps in identifying with a group and feeling like we belong. The question, of course, is what price are we paying for it?

The Three R’s of Social School

So what happens when we break the behavior code of our group? Do the group members rein rebels in or cut them off? It depends on the situation—and the group. Part of establishing a group’s norms involves deciding how much leeway members have to stray from them.

In any group, if we disagree too much with accepted beliefs or customs, we may no longer be welcome in the group. And while the degree of deviation that is tolerated varies from group to group, they all rely on the same strategies to keep group members in line: ridicule, re-education, and rejection.

Warning: Check Your References

Cosmopolitan. Glamour. Vogue. Anyone who reads these magazines is inundated with images of gorgeous women and handsome men. Women’s magazines capitalize on our desire to be members of the “beautiful people club” and the fashion pictures and advice gives us information on how to gain admission.

When we belong or hope to belong to a group, we refer to the group’s standards and customs for information, direction, and support. This group becomes our reference group.

DEFINITION

A reference group is a group to whom we look to get information about what attitudes and behaviors are acceptable and appropriate. It can be a formal group (church or club) or an informal one (peers or family).

The more we aspire to belong to a group, the more influence it will have on us—even if we don’t know any of its members and they don’t know us. Odds are we’ll still direct our energy toward being like the people we hope will accept us. In placing too much emphasis on aspirational reference groups, however, we can get a distorted view of what the group is actually like.

INSIGHT

A reference group can be a powerful force. Women entering Bennington College in the 1930’s brought conservative values into a liberal political and social environment. Not only had their conservatism disappeared by their senior year, but 20 years after graduating they were still liberals.

Nonconformists Are Hard to Find

It’s easy to understand how we might conform to group norms when the group means a lot to us; we all want to be accepted and approved. And when a situation is unclear, we are likely to rely on others for cues as to the appropriate or acceptable way to act.

But even if we don’t need the strokes, we all want to know the right way to act in any given situation. When we’re not sure, we typically turn to others in the situation for clues to help us understand what’s happening. And, for some reason, we tend to automatically assume that other people around us know what to do.

Social psychologist Solomon Asch, a firm believer in the power of social influence, wondered whether social cues could actually be stronger than the real facts. In his study, college students were shown cards with three lines of differing lengths and asked which of the three was the same length as a separate, fourth line. The lines were different enough so that mistakes were rare, and their relative sizes changed on each trial.

On the first three trials, everyone agreed on the right answer. However, on the fourth trial, members of the study who were in cahoots with the researcher all agreed that the wrong line was correct. The subject had to then decide whether to go along with the incorrect majority or go out on a limb and stick with the right answer.

Asch found that 75 percent of the student subjects conformed to the false judgment of the group one or more times. Only a quarter of them remained completely independent. Through a series of experiments, he also found that people were more likely to stick to their guns if there was someone else in the group who also bucked the status quo, if the size of the unanimous group was smaller, and if there was less discrepancy between the majority’s answer and the right answer.

The Asch effect has become the classic illustration of how people conform. Unless we pay close attention to the power of the situation and buffer ourselves from it, we may conform to group pressure without being aware that we’re doing so.

PSYCHOBABBLE

One way to increase conformity is to make the target less than human. During World War I, the “willingness to kill” among soldiers was only 15 percent, despite the fact that most of them were familiar with guns and hunted. To raise willingness, the army uses video games as training tools; the kill ratio went up to 90 percent.

The Shocking Truth About Obedience

Most of us still can’t understand how Adolph Hitler managed to transform rational German citizens into mindless masses who were unquestioningly loyal to an evil ideology. It was no mystery, though, to social psychologist and renegade researcher Stanley Milgram. Through a series of experiments, he showed that the blind obedience of Nazis was less a product of warped personalities than it was the outcome of situational forces that could influence anyone—even you and me.

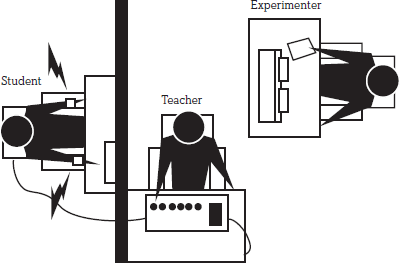

In a controversial experiment, Milgram told volunteers they were participating in a study of the effects of punishment on learning and memory. The alleged goal was to improve learning and memory through a proper balance of reward and punishment. Volunteers were assigned roles as teachers; unknown to the “teachers,” the “learners” were actually actors who knew what the test was really about.

Before the experiment, each teacher was given a real shock of about 75 volts to feel the amount of pain it caused. The role of the learner was played by a pleasant, mild-mannered man, about 50 years old, who casually mentioned having a heart condition but said he was willing to go along with the experiment. Each time this learner made an error, the teacher was instructed to increase the level of voltage by a fixed amount until the learning was error-free. If a teacher resisted, the white-coated authority figure restated the rules and ordered the teachers to do their jobs.

In reality, the learner never received any electric shocks but the teacher believed he was. The true goal of increasing the level of shock was to find out just how much punishment the teacher was willing to deliver.

Beforehand, psychiatrists had been asked to predict how much shock the “teachers” would be willing to deliver; most guessed that the majority of them would not go beyond 150 volts. They predicted less than 4 percent would go to 300 volts and less than .01 of a percent would go all the way to 450 volts; presumably, the 450 volters would be the real “sickies” whose personalities were abnormal in some way.

Boy were they wrong! The majority of teachers obeyed the researcher completely. Nearly two thirds delivered the maximum volts to the learner, and the average teacher did not quit until about 300 volts. No teacher who got within five switches of the end ever refused to go all the way. Most were very upset by what they were doing; they complained and argued with the researcher, but nevertheless they complied.

When Authority Rules

Milgram concluded that we are most likely to obey an authority figure when:

- we see a peer blindly complying with the authority figure

- we can’t see or hear the target of the violence

- we are being watched or supervised by the authority figure giving the commands

- the authority figure has a higher status or more power

- we can feel like we are merely assisting someone else who’s actually doing the dirty work

These are situational factors, not personality characteristics. In fact, personality tests administered to Milgram’s subjects revealed no personality trait differences between the people who obeyed fully and those who ultimately refused to give more shock, nor did they identify any mental illness or abnormality in those who administered the maximum voltage.

INSIGHT

Additional research demonstrated that normal, compassionate college students–often crying and protesting–continued to “shock” a puppy at the command of the experimenter. The puppy was actually not harmed.

Demanding Characteristics

We are constantly getting cues about the right thing to do in any given situation. We get these cues, often called demand characteristics, from watching other people, from direct instructions, or by watching the behavior or tone of the leader.

When we’re around a person in a position of authority, there is an underlying pull toward obedience—to behave as expected by the authority. This is called a demand characteristic. Being a student often makes us hesitant to question or challenge a professor, even when we believe we have a good reason for doing so. We may leave our doctor’s office and realize we were too intimidated to question his diagnosis even if we view ourselves as independent thinkers.

The undertow of demand characteristics can drown even the most educated professional’s judgment. In a study assessing demand characteristics in a hospital setting, 20 out of 22 nurses obeyed fake physicians’ orders and began to administer twice the clearly labeled maximum dosage of a drug (which was actually a harmless substance). Even when we have good reasons to defy authority, it can be incredibly hard to do so.

INSIGHT

One of the best ways to avoid giving in to peer pressure–and stay out of a risky situation—is to be ready for it. Use humor to deflect a request you don’t want to comply with and have a ready-made excuse (even if it’s exaggerated) that allows you to leave or decline.

Viva la Minority!

When it comes to psychology, as in life, the majority often rules, which is one reason why we have spent several rather grim pages talking about our built-in tendency to obey authority, to give in to social pressure, and to be molded by the situation around us. But there are people who don’t obey blindly, who wouldn’t shock a person or a puppy, or who wouldn’t follow the doctor’s orders if they were bad ones. What makes these brave individuals different from the majority of us?

Surprisingly, the answer is rather simple. These are people who truly feel responsible for the outcome of their actions. The two nurses in the group who felt equally responsible for their patient’s welfare bucked the trend by refusing to administer the drug. The more responsible we feel for what happens, the less likely we’ll ignore our moral compass.

This may not be as altruistic as it seems. In fact, taking responsibility may simply mean we know there’s no one else we can blame! Our willingness to obey an authority increases if that authority can be blamed for any wrongdoing. On the other hand, if we feel like the buck stops here or if we share responsibility with the person giving the order, we’re more likely to resist any behavior that can cause someone harm.

How to Be a Rebel

Knowing how to resist is one way to escape the conformity trap. If we don’t know how to stick to our guns, we may wind up saying “yes” when a person persists after we’ve already said “no.” Many salespeople and manipulators count on the ability to persuade others to change their mind. And finally, we all have an ingrained habit of obeying authority without question.

One of the best ways to resist unwanted influence is to build in a delay before we make a decision. Whether we’re resisting the pressure to do our boss yet another uncompensated favor or being strong-armed into paying more for a car than we want to, if we take a “time out” to think things over, we can give ourselves the space to make sure we’re swimming in the right direction. Also, getting a second opinion from a doctor, doing some comparison shopping, or talking things over with a colleague or an expert can get us out of the immediate situation (and the urge to act in a certain way) and into a balanced frame of mind.

PSYCHOBABBLE

A study found that, when a man allegedly in need of assistance was slumped in the doorway to the church, only 10 percent of the seminary students helped when they were late for their sermon! This probably wouldn’t happen in France, where Good Samaritan laws require citizens to assist someone in trouble (or face arrest).

Give Me Some Help Here

In March 1964, 38 respectable, law-abiding citizens watched for over an hour as a killer stalked and stabbed a woman in three separate attacks. Not a single person telephoned the police during the assault. One person eventually did—after the woman was dead.

In August of 1995, a young woman named Deletha Word was chased and attacked by a man whose fender she had dented. She eventually jumped from a bridge after threatening to kill herself if her attacker continued to beat her. Two young men, who actually jumped into the water in an attempt to save her, later described the other onlookers as standing around “like they were taking an interest in sports.”

The newspaper accounts of these tragedies stunned millions of readers and drew national attention to the problem of bystander apathy, an apparent lack of concern from people who had the power to help.

It turns out that the problem isn’t necessarily that no one cares; it’s that bystanders tend to think someone else will come to the rescue. Research has found that the best predictor of whether someone will try to rescue a person in trouble depends on the size of the group in which it happens; the more people who see what’s going on, the more likely it is we’ll assume that someone else will make the phone call or help the driver stranded on the side of the road. The technical term for this “pass the buck” philosophy is diffusion of responsibility.

DEFINITION

Diffusion of responsibility is a weakening of a person’s sense of personal responsibility and obligation to help. It happens when a person perceives that the responsibility is shared with other group members.

That’s the bad news. The good news is that, like heroic Lawrence Walker and Orlando Brown jumping in to help Deletha Word, people do help more often than not. In a staged emergency inside a New York subway train, one or more persons tried to help in 81 out of 103 cases. Certainly, the offers of assistance took a little longer when the situation was grim (the subject was bleeding, for example), but they still came. And if just one person steps in to help it has a domino effect on the onlookers; they are also more likely to assist.

Transforming Apathy into Action

Sometimes, we can convert apathy into kindness just by asking for it. The next time you could use a helping hand, increase your chances of getting help by doing the following:

Ask for it. “Help me!” You might think a person would have to be in a coma to miss your need for help, but don’t assume it.

Be specific. Clearly explain the situation, and tell the person what she could do. “My mom just fainted! Call 911 and give them this address!”

Single someone out. “Hey, you in the red shirt, please call for a tow truck.” There’s nothing like being volunteered out loud to get people to take responsibility and help others.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Experiments showed that when bystanders had temporarily agreed to watch someone’s belongings and then a “thief” (research accomplice) came along and stole them, every single bystander called for help. In fact, some of them even chased the thief down and tackled him!

Fields of Prophecies

What we believe and expect from each other has tremendous power in our relationships. Social psychologists use the term self-fulfilling prophecies to describe the circular relationship between our expectations and beliefs about some behavior or event and what actually happens. In fact, much research suggests that the very nature of some situations can be changed for better or worse by the beliefs and expectations people have about them. In essence, we often find what we are looking for.

DEFINITION

Self-fulfilling prophecies are predictions about a behavior or event that actually guide its outcome in the expected direction.

For example, if you’ve been in a bad relationship, it might be easy for you to believe the worst of the next few guys you date. If you’ve been hurt enough, you may start to believe the contents of every date’s emotional suitcase looks the same. And you may find what you’re looking for—either by picking men with similar challenges or focusing on behaviors that confirm your dour expectations.

As you can see, relationships exist as much in our heads as they do in our actual interactions. Over time, it’s natural to form expectations and beliefs about how relationships should work. But negative expectations and beliefs can create a vicious cycle that serves to confirm our worst fears and dour predictions.

Sometimes, though, our expectations and beliefs about people arise less from our personal experiences and more from family legacies and cultural myths—in a word: prejudice.

DEFINITION

Prejudice is a learned negative attitude toward a person based on his or her membership in a particular group.

Prejudice: Social Reality Running Amok

A prejudiced attitude acts as a biased filter through which negative emotions and beliefs cloud the perception of a target group. Once formed, prejudice tempts us to selectively gathering and remembering pertinent information that will reinforce our existing beliefs. If we think cat owners are sneaky, we are going to find cat owners who are, and we are going to remember them.

Third-grade teacher Jane Elliott was worried that her pupils from an all-white Iowa farm town might have trouble understanding how difficult and complex life can be for different groups. So one day she arbitrarily stated that the brown-eyed students were “superior” to the blue-eyed students. The brown-eyed students, whom she categorized as more intelligent, were given special privileges the blue-eyed students did not receive.

PSYCHOBABBLE

Do you think it doesn’t matter what others think of us? Elementary school teachers were told that certain students were “intellectual bloomers” who would make great academic strides over the next year. By the end of the school year, 30 percent of these randomly assigned children had gained an average of 22 I.Q. points and almost all of them had gained 10.

By the end of the day, the schoolwork of the blue-eyed students had declined, and they became depressed, pouty, and angry. The brown-eyed geniuses were quick to catch on to a good thing. They refused to play with their former friends and began mistreating them. They got into fights with them and even began worrying that school officials should be notified that the blue-eyed children might steal their belongings.

When the teacher reversed the hierarchy on day two, the exact same thing happened in reverse. The blue-eyed children got their revenge, and the brown-eyed children learned what it was like to feel inferior. Not only does this show how easily prejudice can start, imagine what happens to children who experience it every day.

In this chapter, we’ve seen how people can buckle under group pressure and can rise above the toughest problems. We’ve shown how people often live up to our expectations of them; if we expect good from someone, he usually delivers. If we let someone know we care, he usually cares back. And if we ask for his help, he almost always grants it. We are still evolving, but let’s hope we never lose that special and mysterious complexity that makes us human.

The Least You Need to Know

- Social psychologists believe that the situation we’re in, rather than our personality, is a much better predictor of what we’ll do.

- Social situations influence behavior through the rules, roles, and norms established by the society or a group to which we belong; when we don’t follow the group, we risk being ridiculed, rejected, or re-educated.

- Even the nicest people will follow orders to inflict pain if they believe others will do the same thing or if they fear rebelling against authority.

- If we take responsibility for what happens and take a time-out when we feel pressure to conform, we, too, can be rebels.

- Our attitudes toward and expectations of other people or groups are often influenced by prejudices we all learn from family or peers or cultural background.