Like an excited child playing with his favorite toy, twenty-nine-year-old Emil stroked the wheel of the white Cadillac with his strong hands. He wore a black chauffeur’s uniform and a white visored cap. He was a Polish Catholic, tall and dark, the private chauffeur of the Stolowitzky family. His loyalty was rewarded with what was most important to him: a good salary, a heated room, and three meals a day.

The Cadillac rolled over the pocked road from Warsaw to the village, the soft springs blocked the jolts from the potholes in the worn pavement, and Emil glanced now and then into the rearview mirror at his employers in the backseat. Jacob Stolowitzky, a short, high-strung thirty-six-year-old, in a hunting suit and leather boots, was smoking a thick cigar; his wife, Lydia, thirty-four years old, beautiful as a princess, in a dress as white as snow, was pleading with him to stop smoking; and their two-year-old son, Michael, rosy-cheeked and silent, in an immaculate tailored suit, was chewing on a piece of chocolate. In the front seat, next to the driver, sat the nanny, Martha.

Martha was thirty years old, short and thin, with a stern face. She took good care of Michael, imparted knowledge, and taught him obedience, manners, and courtesy. His parents were satisfied with his education. They raised him with love and didn’t want him to lack anything. Not an hour went by that Lydia didn’t come to see how he was, to hug and kiss him. She knew she would probably not have any more children. The doctors agreed that she would almost certainly not get pregnant again. She and her husband were sure that Michael would be their only heir.

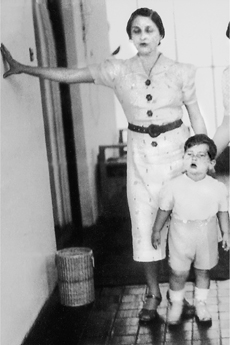

Lydia and Michael Stolowitzky. Warsaw, May 1938.

Happy and carefree as they delighted in thoughts of the vacation in store for them on their summer estate, the Stolowitzky family sank into the soft leather seats of the American car and waited patiently for the trip to end.

The road went through sleepy towns and poor villages. Farmers looked in amazement at the magnificent car, the only one of its kind in all of Poland. Jacob Stolowitzky glanced at them with a cursory indifference, his wife rubbed French cream on her hands, and Michael glued his eyes to the window to look at the people in shabby clothes who gazed at the vehicle as if it had come from another world. Michael never saw people like that on Ujazdowska Avenue in Warsaw, around the four-story mansion. They weren’t part of his world; he wasn’t part of theirs.

Like his father, Jacob Stolowitzky was an experienced businessman, calculating and clever. He expanded the family business empire, acquired coal and iron mines, land, and houses, signed partnership agreements with companies all over the world, employed hundreds of workers, and deposited most of his money and gold in secret Swiss bank accounts, deducting part of it for charity. Emissaries from the Land of Israel who came to Poland were entertained generously in the home of the Jewish tycoon and always left with contributions, even though they could never extract a promise that he would ever settle in the Land with his family. “What will I do there?” he responded to their attempts to convince him. “I’m just fine here.”

Poland was indeed good to him. Abundantly wealthy, the Stolowitzky family led an enviable life. They employed as many servants as they liked, bought clothes and jewelry in the capitals of Europe, and sailed on the Adriatic every spring on a luxurious yacht, once even with the Duke of Windsor and his lover, Mrs. Simpson. They hosted dinners in their mansion for the elite of Poland and entertained famous guests from abroad, hired well-known artists to perform in the grand ballroom on the second floor of their house, and spent their vacations on their summer estate two hours away from Warsaw.

Jacob Stolowitzky. July 1929.

It was a large estate in a picturesque region. A thick forest and fruit and vegetable gardens covered a considerable part of the land, and at its edge was a clear, beautiful lake. Some of the wooden cottages in a clearing of the forest were for the family and their guests, and others for the workers who maintained the estate off season.

At last they arrived. Two armed guards hurried to open the big iron gate and bowed to the Cadillac that stopped at the central wooden home. As always, Emil carried Michael on his shoulders and galloped with him to the house. After he put Michael down in the big vestibule, Emil went to the garden and picked a bunch of flowers, came to Lydia, and gave them to her. “You never forget,” she said. She smiled at him indulgently and her husband tapped him on the shoulder affectionately.

“How could I forget,” replied Emil in a flattering voice. “You’re like a mother to me.”

The aged housekeeper of the estate greeted the family with obsequious bows and hurried to move their things from the car to their rooms. The rooms were furnished with expensive simplicity. On the beds were white sheets and soft down comforters; from the open windows overlooking the forest came pungent smells of pine trees and a symphony of chirping birds and animals. The weather was nicer than usual. Cloudless blue skies stretched overhead and flowers bloomed in the well-tended garden.

Throughout the day, many preparations were made around the estate. Close relatives, friends, and business partners invited to share their vacation were brought in carriages from the railroad station or arrived in cars driven by their private chauffeurs. Roars of laughter and pleasant conversations accompanied the abundant lunches served in gold dishes on a dining table that had belonged to the royal family four hundred years earlier. Children ran around and played on the lawns; babies and their nannies sunbathed.

Dinner was just as extravagant as lunch. When it was over, Lydia gathered her guests in the ballroom and presented a famous chamber orchestra brought especially from Warsaw. After the concert, the men smoked cigars and the women sipped warmed cognac. Servants put candy on pillowcases and prepared to shine the shoes the guests left outside their rooms at night.

At dawn the next day, accompanied by the forest guard of the estate, the family and their guests went out on horseback to hunt and fish. They hunted pheasant and fished for turbot and then sent them to the kitchen to be cooked for dinner. During the afternoon break, the servants spread white cloths on the banks of the lake and set them with various delicacies and bottles of wine. Lydia read her son a story and Martha, the nanny, went for a horseback ride.

When evening fell and everyone prepared to return to the house, they discovered that Martha had disappeared. Lydia and Jacob were frightened. Martha was extremely punctual and was never late or absent without a reason. Jacob waited a little while and when she didn’t return, he gathered a group of riders and went out to search for her. They found her some way off, among the trees of the forest, lying on the ground, groaning in pain. The horse she had been riding was lying next to her with a broken leg. “He stumbled on a rock,” she muttered. The servants improvised a stretcher of blankets and hunting rifles and carried her to the summerhouse.

The Stolowitzky family was devastated. Martha wasn’t only a nanny; she had quickly become a beloved and appreciated member of the family. Michael sobbed and Lydia called Emil to take the injured woman to the hospital in Warsaw. She herself went with them. An initial examination revealed a bad break in her left knee and hemorrhages in her arms. The doctors were concerned. “Unfortunately,” said one of them, “it will take a lot of time for her to recover.”

Lydia didn’t return to the summerhouse. Martha’s condition depressed her so much that Lydia stayed for several hours at Martha’s bedside, trying to relieve her pains and cheer her up. Never had she been so close to human distress, to grief and disaster. She felt Martha’s pains and prayed for her recovery.

It was supposed to be a happy day, a milestone in the life of Gertruda Babilinska. She and her family had been waiting for this day, and Gertruda was thrilled when it came at last.

In their small house in Starogard, near Danzig, three hours from Warsaw by train, the excited family dressed in their wedding clothes and set off for the church, where Gertruda was to be married. She was the oldest child, the only daughter.

Gertruda was charming, nineteen years old, tall and fair, a teacher in the local school. Her students and colleagues loved and admired her, and at the end of every school year, her students’ parents showed their appreciation with an expensive gift. She planned to go on teaching even after she was married, at least until she had her first child.

Many good men had courted Gertruda, but she was in no hurry to accept them. She examined each of them carefully and ended the relationship when the suitor failed to touch her heart. She wasn’t interested in marriage for money or status. She believed in love. She met Zygmunt Komorowski in the home of mutual friends. He worked in an import-export office in Warsaw, was a handsome and well-groomed man ten years older than her, and he liked Gertruda the moment he met her. He was impressed with her broad education, her expertise in German, and her pleasant ways, and he lavished compliments on her that made her blush.

Zygmunt was a man of the world, an experienced urbanite, who won her heart with his courtesy and his stories about the big city and the global business he was engaged in. After a few months of courtship, one evening, in the best restaurant in Starogard, Zygmunt proposed marriage. Gertruda, who believed that she had at long last found the love of her life, gladly accepted. He promised to take her to Warsaw, buy them a big apartment, support her in style, and give her lots of love.

The couple decided to get married in the local church of Starogard and to hold a reception afterward in the home of the bride’s parents. Her mother and her relatives worked day and night preparing food for the party and walked, in a big group of family and friends, to the church in the town square. Gertruda, excited and tense, wore a white wedding gown she had bought in Danzig.

Family and close friends gathered in the church, and the bride’s students stood outside and applauded her as she approached. Flushed, Gertruda clutched a small bouquet of violets and, in a trembling voice, thanked everyone for their good wishes.

In the church, everything was ready for the ceremony. An old man sat waiting at the organ. The priest smoothed his robe and Gertruda’s parents shook hands warmly with the last guests. Everyone was waiting for the groom, who was about to arrive with his parents and sisters, but Zygmunt was late. A long time had passed when a messenger appeared in the church door with a short letter for Gertruda. In it, the man of her dreams told her that for unspecified reasons, he couldn’t go through with the wedding. He concluded with an apology for the grief he had caused her and wished her good health and happiness. Gertruda burst into tears, ran home, and locked herself in her room.

For three days she lay on her bed in her wedding gown, didn’t eat, didn’t see anyone, and didn’t stop sobbing. When she finally came out of the room with her eyes red and her face pale as a ghost, she told her parents quietly that she had decided, because of the disgrace, that she could no longer stay in the town. Her parents, still stunned by what had happened, didn’t even try to change her mind and only asked what she intended to do.

“I’ll go to Warsaw. I’ll find work. I’ll try to get over it. Nobody knows me there,” she said.

“Just promise me that you’ll come back,” said her mother.

It was hard for Gertruda to promise. “How can I know what will happen to me?” she replied. “Maybe I’ll find a new bridegroom there.”

She went to the school to announce her resignation. The principal expressed his profound disappointment. He tried to convince her to stay. He said that her students were waiting eagerly for her, that the wounds would heal in time, and that the big city where she was heading generally didn’t welcome strangers from remote towns. She paid no attention to his words and asked for a letter of recommendation. The principal gave her a warm letter and said an emotional farewell. She returned home, packed her few things in a small suitcase, hugged her parents, collected her little bit of savings, and boarded the train to Warsaw.

With the help of an acquaintance, Gertruda found a job as a nanny for two young daughters of a well-to-do family. She worked there for a number of years until the family left the city. Gertruda returned to her hometown but never managed to adjust to her old surroundings. After a few years of struggling, she again packed up her belongings and set out for Warsaw to find a new job.

The capital city greeted her with a downpour. She wandered through the streets, frozen, vainly seeking shelter beneath her umbrella. The wind swirled the raindrops and blew the umbrella out of her hands; she got soaked to the skin. She ran back to the railroad station, where she sat in the heated waiting room until her clothes dried. When the rain stopped, she left the station and began combing through the nearby alleys until she saw a sign in the door of one of the houses with peeling plaster announcing an apartment for rent. The staircase reeked of cooking smells, the landlady was coarse, but the rent was low enough to persuade her to take the apartment. Gertruda put her clothes away in the shabby wardrobe and looked out the window at Warsaw in the dark. The first lights came on in the windows of the city and suddenly the idea that she would stay there for an indefinite period of time made her afraid that she would encounter only more disappointment. Nevertheless, she had no choice. She felt she couldn’t go back home again. She had to make every effort to fit in.

Her meager savings would last only a few weeks if she was frugal, and she knew she had to find work soon. She was also sure she couldn’t bear to be idle for long, couldn’t endure the days without people around her, and she knew she had to make a living.

The rain began again. Gertruda stretched out on her bed and fell into a nightmare sleep. When she woke up early in the morning, she hurried to a small café, drank a cup of coffee, and scanned the want ads in the morning paper. There were ads for shopgirls, cooks, and clerks. She ignored those and went on looking until one of the ads caught her attention. She read it over and over:

HONORABLE FAMILY IN WARSAW URGENTLY SEEKS A DEVOTED NANNY, NO HOUSEWORK, FOR A TWO-YEAR-OLD CHILD. LODGING AND A GOOD SALARY ARE GUARANTEED. PLEASE CONTACT THE STOLOWITZKY FAMILY, UJAZDOWSKA AVENUE 9.

The job was just what she was looking for. She loved children, could help them when they needed it, could listen to them. If the working conditions were good, she decided, she would take the job.

Gertruda left the café and set off for the address in the newspaper. The city stirred around her for another day of bustling activity. The sky was gray, stores opened one after another, and people hurrying to work filled the trolleys.

Her heart beat with excitement when she came to Ujazdowska Avenue. She loved the splendid houses where rich people and government leaders of the city lived and the shining cars that glided out through the cast-iron gates. There were no such houses in Starogard.

She rang the gold-plated doorbell of number 9. There was a long minute of silence until an elderly maid stood in the entrance.

“I came about the ad,” said Gertruda.

Impassively, the woman scanned her from head to foot.

“Come in,” she said. Gertruda stepped hesitantly into the vestibule. Around her, everything—every statute, every picture on the wall, the grand staircase to the second floor, the bouquets of flowers filling gigantic vases—radiated wealth she had never known. She had never heard the name Stolowitzky.

The maid took her coat and led her into a small room whose windows looked out onto a garden.

“I’ll tell Mrs. Stolowitzky you’ve come,” she said and left.

Gertruda sat down on the edge of the velvet sofa, careful not to dirty the expensive upholstery. She was afraid the mistress of the house would be a harsh and arrogant woman, like those wicked rich people she had read about in novels. She hoped the lady wouldn’t be contemptuous of her simple clothes and wouldn’t set demands she couldn’t meet. Furtively she straightened her dress and tried in vain to hide her hands, which seemed too clumsy. Well, she said to herself, I really don’t belong here; they must be expecting a nanny with experience taking care of rich and spoiled children, while I have only taught schoolchildren in a poor town. The longer she sat there, the surer she became that she had no chance.

The door opened and she saw a beautiful woman, elegantly dressed, who looked at her warmly. Gertruda got up, embarrassed.

“Sit down,” said the woman softly. “Will you have some tea?”

“No, thank you.”

The woman held out a delicate hand. “My name is Lydia. What’s yours?”

“Thank you for coming,” said the lady of the house. “You’re very quick. We put the ad in only this morning and no one has come but you. Where are you from?”

Gertruda answered briefly.

“Do you have experience?”

“Yes, I do,” Gertruda said. She gave the woman a letter of recommendation from the father of the household where she worked before.

Lydia Stolowitzky scanned it.

“He writes very good things about you,” she commented.

Gertruda blushed.

“Are you married?” asked the woman.

“No.”

“Tell me about your family.”

Gertruda did.

The woman looked at her for a long time. “I assume you’re not Jewish,” she said.

“I’m Catholic.”

Lydia Stolowitzky surprised her. “We’re Jews,” she said.

Gertruda looked at her in amazement mixed with fear. Jews? She didn’t expect to work for people like that. In her town there were no Jews. Once a family of Jewish merchants did try to settle in the town, but various residents made their life so miserable that they were forced to leave. She had heard horror stories about Christian children murdered by Jews on Passover so that their blood could be used for the holiday ritual. There were other wicked rumors, half-truths and harsh libels about the Jews, and she was sure she couldn’t stay in that house.

“I … I don’t know if that would suit me,” she said sadly.

“Why?” Lydia Stolowitzky wondered.

“Because you’re Jews and I’m Catholic,” she replied frankly.

The woman smiled. “Our previous nanny was also Catholic. That didn’t bother her or us.”

Gertruda stood up. “I’m sorry,” she said.

“So am I,” replied Lydia.

“I hope you find a suitable nanny,” said Gertruda. “I’m sorry for taking your time.”

She turned to the door.

“Before you go,” said Lydia, “I want you to know that I like you. If you should decide nevertheless to take the job, come back to me. I’ll be glad to talk with you again.”

Gertruda went outside and a cold wind from the river, mixed with tiny raindrops, struck her face. She couldn’t decide whether she had acted properly in turning down the offer, but she doubted she’d find a better one.

For a whole day, she wandered around, helpless. More than anything she now needed somebody who would understand her and tell her what to do, but in the big, strange city, there wasn’t anyone who could do so. Only one person, far from here, could come to her aid and she decided to go to him. With a heavy heart, Gertruda boarded the train at the Warsaw railroad station and went home. Cityscapes changed to green fields and farmers working their land. The smell of plowed earth, mixed with the bitter smoke from the locomotive, whirled in her nostrils when she stood at the open window in the passenger car. The smells and sights brought her back home, to where she was born, grew up, went to school, and made a living. She became depressed as the train slowed down and stopped at the small station of Starogard. Even though she had been gone only a couple of days, it was only now that she understood how much she missed her parents.

From the railroad station, she went straight to the small church in the middle of town and entered the open door to the empty hall. Candles were lit on the small platform and the statue of the crucified Jesus with a gilded crown of thorns looked at her. She knelt, dropped her head, and said a silent prayer.

Quiet footsteps passed by her and somebody called her name. She raised her eyes to the priest standing next to her, smiling.

“Gertruda, my child,” he said quietly. “Welcome. I thought you left here and wouldn’t return for a long time.”

“I came back to ask your advice.”

The elderly priest had known her since she was a child. He also knew her devout Catholic parents, regular churchgoers.

“How can I help you?” he asked.

She told him about her attempt to find work in the Stolowitzky house in Warsaw. “The problem is that they’re Jews,” she said softly.

The priest waited for her to go on, but she had nothing to add. She hoped he’d understand.

“You came for me to tell you if it’s all right to work for Jews?” he asked.

She nodded.

“Did they make a good impression on you?”

“Yes.”

“And what exactly bothers you about them?”

“Nothing specific, but I don’t know their customs. I don’t know if they’d let me go to church or even hang the pictures of the saints in my room. I’m not sure I’ll feel comfortable there.”

The priest put his hand on her shoulder.

“There are good Christians and bad Christians and good Jews and bad Jews,” he said. “The most important thing is that they’re good people, who will love you and whom you will love. I’ve got a feeling that you’ll be happy there.”

“I hope they really are good people,” she said.

“So do I, my child. Go in peace and may God protect you.”

She left the church, went to her parents’ house, and told them about her conversation with the priest. They begged her to stay but she refused. Her father tried to persuade her to find work where there were no Jews.

The next day, all the way back to Warsaw, through the monotonous rattle of the train wheels, Lydia Stolowitzky’s last words echoed in her ears: “Come back to me, I’ll be glad to talk with you again.” She hoped no one else had taken the job in the meantime.

Lydia Stolowitzky greeted her with a broad grin.

“I was expecting you,” she said. “I had a feeling you’d come back to me. Come, I want you to meet Michael.”

They went up to the second floor, to a fine nursery. A rosy-cheeked boy sitting on the carpet and playing with an electric train, raised his blue eyes to her.

“Say hello to Gertruda,” said his mother. “She’s your new nanny.”

The boy looked at her inquisitively.

“Want to play with me with my train?” he asked in a clear, ringing voice.

Her heart skipped a beat. He was so beautiful, so well-groomed, and so polite that she wanted to press him to her heart and kiss his soft cheeks.

“I’d love to play with you,” she replied, and sat down next to him. When she looked around a few minutes later, Lydia had gone.

Gertruda’s fears vanished in the following days. Life in the Stolowitzky house was easier and nicer than she had imagined. Lydia Stolowitzky never made her nanny deny her faith; she let her hang the pictures of Jesus and Mary on the wall of her room and put a crucifix on her nightstand. Lydia herself wasn’t observant, and while her husband, Jacob, did contribute a lot of money to the synagogue, he didn’t attend services frequently. He was a busy man and didn’t spend too much time at home. Lydia was devoted to volunteer work in social organizations, read for pleasure, entertained a lot, and played the piano. Gertruda chose Sunday as her day off, when she attended church.

Michael came to love her as a member of the family. Her comfortable room was next to his and she was always willing to come to him. When he grew a little older, she taught him to read and write, and took him to museums, holding his hand. She loved taking care of him. She sent photos of the two of them to her parents and wrote them that she had never been so happy in her life.

In the evening, before he went to sleep, she sang him the lullabies her mother had sung to her when she was a little girl, and when he was sick, she sat at his bed day and night until he recovered. She watched him as the apple of her eye, bought him gifts with her own money. In time, he became much more to her than a child she was paid to care for: he was the child she had wanted so much to have but couldn’t. “You’re my dear son,” she whispered in his ear every night after he fell asleep. “My only beloved son.”

• • •

Gertruda walked around the big house quietly, trying not to bother anyone. She made friends with the servants and helped the cook when there were guests. Her salary was decent and she managed to save a large part of it.

Michael was a talented child. At the age of two, he began playing the piano, with a private teacher who came to the house twice a week, and he loved reading children’s picture books. Gertruda adored how he looked, his pleasant manners, his clear voice when he sang popular songs with her. He spent more time with her than with his mother, loved to hear the bedtime stories she read to him, and missed her when she went to visit her parents.

On Sunday, when she went to church, he would go with her to the gate and wait for her in the yard. Often he wanted to go inside and see what was going on, but she refused to let him. “You’re Jewish,” she said. “You don’t belong in church.”

Once a week she went with him to visit Martha, the former nanny, who had now recovered. The two women became friends and Gertruda offered to give up her place if Martha wanted to return to work. Martha was glad, but Michael wasn’t. “I love Martha,” he told Gertruda, “but I love you more.” Lydia insisted that Gertruda continue as Michael’s nanny. That week, Jacob Stolowitzky paid Martha a large sum of money for her retirement.

Michael didn’t budge from the new nanny: He wanted Gertruda to eat with him at the family table and not in the kitchen like the other workers, and when she told him that her birthday was coming, he begged his mother to give her an expensive gift. Lydia went to a fine shop, bought her a nice dress, made a small party, and gave her the gift. Gertruda wept with joy.

Her whole world was enclosed within the four walls of the Stolowitzky house, as if it had always been her home. Lydia treated her as a sister, the servants respected her as someone superior to them. They honored her and obeyed her and she was careful not to take advantage of her position. She had little to do with the outside world and when the principal of her old school pleaded with her to come back to teaching because the children missed her, she replied politely that she was happy where she was, with people who appreciated and loved her. She exchanged letters with some of her old friends, learned English by correspondence, knitted sweaters for Michael, and turned up her nose at the clumsy courtship attempts of Emil, the chauffeur. After her great disappointment in love, she wasn’t interested in men.

Hava Stolowitzky, Jacob’s mother, died in her bed on September 22, 1938, after a long and difficult illness. Less than three months later, her husband, Moshe, suffered a stroke at a business meeting in his office and was taken to the hospital, where he lay unconscious for a week. When he finally came to, half his body was paralyzed and he spoke only gibberish. His son, Jacob, hired the best doctors for him, sat at his bed day and night, and no one was happier when at long last his father opened his eyes and looked at his son.

“I don’t know if I’ll stay alive,” said Moshe Stolowitzky with a great effort. “Something is worrying me, my son. The situation in Germany is getting worse by the day. Hitler is building a big army, too big, and he’s crazy enough to go to war to conquer all of Europe. I’m afraid that chaos will rule the world, and many businesses will fail. I intend to sell all my property and transfer the money to a bank in Switzerland. That money can be withdrawn in a crisis, invested wisely, and earn several times over. If I die, I suggest you do that instead of me.”

Moshe Stolowitzky died a few days later. Thousands attended his funeral in the big Jewish cemetery in northern Warsaw. He was buried next to his wife, near the grave of the writer Y. L. Peretz. On the Stolowitzky couple’s marble tombstone, inside a stylized iron fence, was a tablet of a hand contributing to a charity box, a reference to their generosity.

With the death of Hava and Moshe Stolowitzky, the mansion and the rest of the property was transferred to their son, Jacob. His wife, Lydia, spent a few months redecorating the mansion to suit her taste. Jacob worked hard to master the many deals his father left him and to guarantee his clients that every contract signed by his father would be honored in full.

Michael grew up like a prince in the fairy tales. His clothes were made by a well-known tailor, the cook made sure the child ate only high-quality food, and Gertruda didn’t let him out of her sight from the minute he woke up to the time he went to sleep.

Lydia was very proud of the new look of the mansion and wanted to impress others with it, too. The housewarming for the new interior was celebrated with a ball for the dignitaries of Poland and the wealthy of Europe. The famous bass singer Feodor Chaliapin, accompanied by the best musicians of Warsaw, entertained the guests with opera pieces in the big ballroom. Wine flowed like water, and the mood was lively.

Jacob Stolowitzky followed his father’s orders and sold most of his properties for good prices. With the help of his friend, the Swiss attorney Joachim Turner, he deposited the millions he received in a few banks in Switzerland. He was sure he was doing the right thing. His father’s advice and his instincts about coming events always turned out to be right.

Ever since her grim struggle to have a child, Lydia Stolowitzky had become superstitious and feared that someday their good luck would run out. Even though there was no obvious reason to fear an impending disaster, she was afraid that something bad would happen to her only son, that happiness would vanish, that the business would collapse. Her husband patiently put up with her long monologues and her accounts of bad omens, and tried in vain to dissipate her anxieties.

If Lydia wanted triumphant proof that her fears had some basis, she got it one Saturday afternoon. It was a warm sunny day and the Stolowitzky family was at the usual Sabbath meal. One maid cleared the plates of the first course and another brought the second. There was a good mood at the table. Jacob told of a new contract he was about to sign with the Soviet government to lay iron tracks from Moscow to Tashkent in Uzbekistan. Lydia suggested that, to honor the event, she would hold a reception and invite a famous violinist. Michael fluently and proudly recited a comic poem from a new children’s book and everyone applauded him.

As they were finishing the soup and the maid was putting a pair of stuffed pheasants on the table, a knock was heard at the door. Everyone looked surprised, since family meals were a strict ceremony and the servants knew that they were not to be disturbed.

The door opened and Emil stood there. He bowed and apologized for the disturbance.

“Come back later,” grumbled Jacob.

“This is urgent!” the chauffeur insisted.

“What’s so urgent, Emil?”

“A woman gave me a letter for you and said it’s a matter of life and death.”

Jacob Stolowitzky put down his fork and opened the envelope. Urgent letters about business were an everyday affair. Messengers came and went from his house even on the Sabbath, but never had they dared disturb him at lunch.

His eyes ran over the note and his face turned pale. He gave the letter to his wife and Lydia gasped.

“What is this supposed to be?” She was amazed.

“I have no idea,” said her husband. “I’ve never gotten a letter like this.”

“I knew it,” groaned Lydia. “I knew our good life couldn’t last.”

The unsigned letter said:

Mr. Stolowitzky,

If you don’t want something bad to happen to you and your family, prepare a million zlotys in cash by tomorrow. Send your chauffeur to the entrance of Kraszinski Park. That will be the signal that you’re willing to deliver the money to us. Afterward, we shall tell you what to do. We warn you not to go to the police.

He read the letter again and again, finding it hard to digest the words.

His wealthy businessmen friends were often targets of blackmailers. One of them was shot as he came out of his house after he refused to agree to their demands. For a long time, Jacob Stolowitzky had repressed the fear that such a thing could happen to him, too, someday. Now it was his turn.

He turned to Emil.

“Who gave you the letter?” he asked.

“A woman I don’t know gave it to me at the house and disappeared.”

“Describe her.”

“Not young, thin, in a black coat. Her head was wrapped in a brown kerchief. She wore sunglasses.”

“Were there other people with her?”

“I didn’t see any.”

“How did she know you work for us?”

“She waited at our gate. When she saw me she approached and waited until the gate opened for me, came to me, and asked if I worked for Mr. Stolowitzky. I said I did and then she gave me the letter for you and ran off.”

Jacob dismissed Emil. Michael looked at his father inquisitively and Gertruda refrained from asking what had happened. Jacob quickly finished eating and withdrew to his room. From there he phoned the police.

An officer and two policemen soon came to the mansion on Ujazdowska Avenue. They collected testimony from the chauffeur and the servants, took the letter, and warned the family members not to go out alone. Jacob took his gun out of his desk drawer and put it in his pocket. Lydia canceled visits to her friends and closed herself in the house. Gertruda was ordered not to take the daily walk with Michael until the police caught the blackmailers.

For a few days nothing happened, and then Emil came with another letter. He said he was driving slowly at a busy intersection in Warsaw when the letter was suddenly thrown through the window of the Cadillac. “It was the same woman who gave me the first letter,” he said.

This letter was also addressed to Jacob Stolowitzky.

Like its predecessor, it, too, wasn’t signed:

We have learned that, against our demands, you did go to the police. We warn you for the last time: if your health and the health of your family are important to you, cut off all contact with the police immediately and pay the money. Send your chauffeur to park the car at the gate of Chopin Park tomorrow at five in the afternoon. We will see that as an agreement to the payment. Further instructions to come.

“They’re following us,” Jacob said to Lydia with a worried expression. “They apparently saw the police come into our house.”

“Or somebody told them about it.”

“Who?” he asked in amazement.

“Any of the workers in the house. The servants, the gardeners, the cook … Every one of them could be a partner in that plot.”

“We’ve always treated them like family. It’s troublesome to think that one of them is plotting to harm us.”

“What do you plan to do now?” she asked.

“Of course, I’ll give this letter to the police. There is no way I’ll give in to these criminals.”

The windows of the mansion on Ujazdowska Avenue overlooked lively Chopin Park. Parents strolled with their children, nannies pushed baby buggies, happy families spread blankets on the lawn and feasted on delicacies.

Michael begged Gertruda to take him for a walk in the park. Ever since the blackmail letters had come, they had been warned not to leave the house. But weeks passed and nothing happened. It was hard for Michael to be cooped up inside, and Gertruda consulted with his mother.

“Take him for just a short walk,” Lydia agreed. “But on condition that Emil watches you.”

Emil was relieved of all his work. The sky was clear when they left the house and entered the park. In the chauffeur’s pocket a gun was hidden, given to him by his employer. Jacob Stolowitzky demanded that Emil stay very close to the nanny and the child.

The three of them ate ice cream in a café on the shore of the lake. Gertruda saw nothing suspicious. She shut her eyes and dozed off in the sun. Michael licked all his ice cream and Emil lit a cigarette.

Soon they headed home. Gertruda and Michael strolled arm in arm and Emil walked behind them. As they were walking, a mass of bushes suddenly loomed up at the side of the path and a man and a woman darted out of it. They attacked Michael and tried to get him out of Gertruda’s arms. The nanny hugged the child with all her might and shouted for help. The man punched her in the nose, and he and the woman continued to pry the child from his nanny’s arms. A few men walking nearby ran up to Gertruda and Michael. The two kidnappers let go and started fleeing. Emil pulled out his gun, shot at them, and started chasing them. Gertruda clutched Michael to her heart and he burst into tears. She asked the men who surrounded her to walk them back to the mansion. When they got home, Lydia gave her son and the nanny one look and was in a panic. She quickly bolted the door behind them.

“What happened?” she wanted to know.

Gertruda told her.

“You’re hurt.”

“It’s nothing,” said the nanny. Her nose was bleeding and her body ached from the blows, but she didn’t complain. The important thing was that Michael was safe. She wouldn’t have forgiven herself if the kidnappers had won.

Lydia brought bandages and antiseptic.

Emil came back some time later. “I chased the bastards, but they were too fast for me,” he said sadly. “I couldn’t catch them.”

The police inspectors heard Gertruda and Emil’s story. The two of them were questioned at length and asked to describe the two kidnappers. “Was it the same woman who gave you the letter for Mr. Stolowitzky?” one of the inspectors asked Emil.

“Yes,” he replied. “It was the same woman.”

“Did you see where they escaped?”

“They left the park and ran to a car that was waiting for them. They got into it and drove off. I shot at the car but it disappeared.”

“What kind of car?”

“A black Mercedes.”

“Did you see the license number?”

“I didn’t have time.”

The inspectors came to Jacob Stolowitzky in the middle of a business meeting downtown. They closed themselves up in his office and told him about the chain of events.

“Somebody apparently revealed to the kidnappers that your child was about to go to the park,” they said. “They laid in wait to kidnap him. Who could have told them about the planned walk?”

“Only the nanny, Gertruda, and the chauffeur, Emil, knew in advance about the walk,” he said.

“How long has the nanny worked for you?”

“More than a year.”

“You’re satisfied with her?”

“Very.”

“And the chauffeur? How long has he worked here?”

“Six years.”

“Who hired him?”

“I did. We put an ad in the paper and he came with good references.”

“Have you had problems with him during the time that he’s worked for you?”

“Never.”

“He may well have cooperated with the kidnappers,” said the inspector. “Remember that he was the person who brought you the two extortion letters. He also knew in advance about the visit to the park. He did shoot at the kidnappers but didn’t hit them. He may have missed on purpose. I think we should arrest him.”

“Do you have any proof?”

“We don’t have any proof, but we do have our suspicions.”

“That’s not enough,” Stolowitzky insisted. “Emil is a devoted and loyal employee. He wouldn’t dare do something bad to us.”

“People are willing to do a lot for money,” said the inspector. “Nevertheless, we do have to consider the possibility that he’s involved in it. Trust our instincts. After he sits in prison awhile, he’ll tell us everything. To be on the safe side, you should look for another chauffeur.”

“Absolutely not,” protested Stolowitzky. “I guarantee that Emil wasn’t involved in this. We’re very satisfied with him and have no doubt that he’s loyal and honest.”

Nevertheless, the police decided to hold Emil for questioning. Bowed and sad, he went with them and came back only two days later.

“They picked on me for no reason,” he complained to his employers. “They threw me into a cell with common criminals and questioned me day and night. But, in the end, they didn’t find anything against me.”