Faces Showing the Stamp of Time

The letter is addressed to me, it is in my handwriting, and I cannot remember writing it or deciding to send it to myself. Everything about it is wrong.

A stamp dealer, of course, gets self-addressed letters all the time. My colleagues around the world have stocks of my labels, as I do of theirs, and on the day of issue of any new stamp they routinely buy a bundle of first-day covers and address a batch of them to me. When I started out as a boy, of course, the envelopes and later the labels were handwritten; later typewritten; but once I began to deal in sizable quantities, I moved swiftly on to printed labels and to rubber stamps. In thirty years, many rubber stamps bearing my name and address have been worn down into illegibility, before I went on to word-processors which could produce labels to order. And since I always have several made up, in reserve, there’s always one to hand when I have to post a stamped-addressed-envelope for some ordinary purpose like requesting a receipt or proof of delivery.

In any case, this envelope is empty. Unsealed, with the flap turned in, as I normally do with s.a.e.’s in case I do want to enclose something in the future. It has all the signs of being one of my own, routine acquisitions, except for the handwriting. That is unusual.

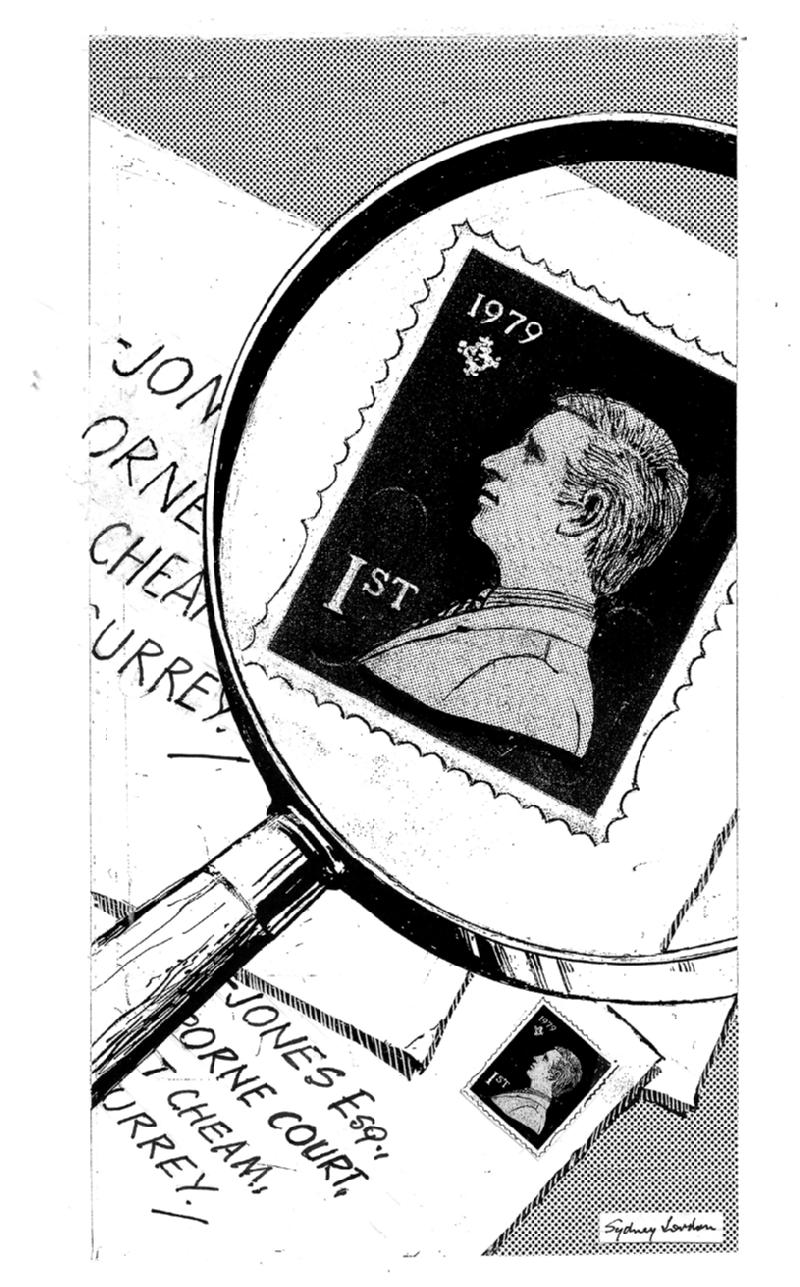

Even stranger is the stamp. It bears a portrait of Prince Charles, and that in itself is striking: as any expert can tell you, a thematic collection on the royal children will scarcely fill a page of an album. Apart from the British commemoratives of the Investiture and his wedding, the rest will be from small countries capitalising on state visits. There are no British stamps showing simply the man himself. And yet at first glance this is a British stamp, because there is no other country’s name on it. Under the conventions of the International Postal Union, the fact that Britain invented the postage stamp confers on us, and on no other nation, the curiously inverted privilege of not putting our name on our stamps. Instead, the rules state, every British stamp must bear the recognisable face of the reigning monarch. It has pushed the Queen’s head into some strange places, in some ill-thought-out designs. Yet on this stamp, there is no Queen’s head at all.

Furthermore, the denomination is two pounds, fifty pence. Now just about everyone knows that large denomination British stamps have castles on them. For all the effects of inflation, we are still far from the point where £2.50 would be the standard price for even a first-class letter. Even now, as I write in 1993, it would be more than a tenfold increase. I could explain it, offhand, in only one way: if I was present at an event of such consequence that I bought copies of every denomination of stamp and mailed them to myself in anticipation of profit—so many that I ran out of the labels I always carry. And one of those envelopes, by some bizarre circumstance, slid back in time to let me know what had happened.

But what was it? I can think of only one thing that would make it worth buying ordinary, day-by-day stamps in such quantities. In a time when the present Prince of Wales was King, I would have to be present at some event involving him so intimately that any stamp featuring him, and franked for that place and time, would be of commercial value.

And now comes the nightmare. The only event I can think of which might do it is a political assassination. The date makes sense: July 1st, 2009, the 40th anniversary of his Investiture as Prince of Wales. In that time, though I wish long life to Her Majesty like any loyal subject, it is entirely conceivable that she will have surrendered the throne to her firstborn son: an event he might well choose to commemorate after the Coronation, with an extra ceremony at Caernarvon, where his mother invested him forty years before. That is the place-name on the postmark, as clearly legible as the date. I can even set some boundaries on the time, because the collection was at 16.15 hours, and whatever happened must have happened at least an hour before—probably longer.

It would be a terrible blow to the nation. It amazes me, even now in my sixties, how few people remember the shock that ran through the land on the death of George VI; how amazed they are when I mention ‘the King’s Christmas broadcast’ or ‘drinking the King’s health’, as if the present Queen has always reigned and always will. Despite the warning of his long illness, people were shocked; telephone switchboards were jammed with queries; Britain went into mourning. A sudden death, especially by violence, would be much worse.

And I know, if not it all, at least enough probably to prevent it. If I do, of course, I will deny myself financial gain; but that is not everything. If that had been my only concern in life, I might have devoted it to larger concerns than dealing in postage stamps. I can truthfully say that I feel no temptation to keep silent for that reason. But what am I to do? If I step forward now, the stamp will be dismissed as a clumsy forgery, the rest the work of a madman. If I wait until the stamps are issued, the accusation will be only that I forged the postmark, easier still.

I am lodging this account now with a Notary Public, along with the envelope, in hopes that it will help to prove my story. My nightmare is that otherwise I will be standing in the crowd, an old man armed with a full set of the envelopes from which I will profit (because I must have them, and post them, for one to come back to me now) and I shall try to attract the attention first of the police, then of the Special Branch, with no evidence except for an envelope whose postmark will then be only an hour or so in the future.

They will thrust me back into the crowd; or, more probably, eject me from the site altogether. It will let me reach a posting box ahead of whatever chaos ensues. The envelope will be launched on its way back to me through time, handwritten as it sits before me now, my address blurred only in the bottom right-hand corner, on the last digits of the postcode. Water has fallen on the envelope there: raindrops, perhaps, as the postman came up the steps to my door. There was rain this morning. Or then again, with no idea as I write of what will happen or how bad it will be—how many others, perhaps, will be victims—perhaps, sixteen years from now, those blurring drops may be my tears.