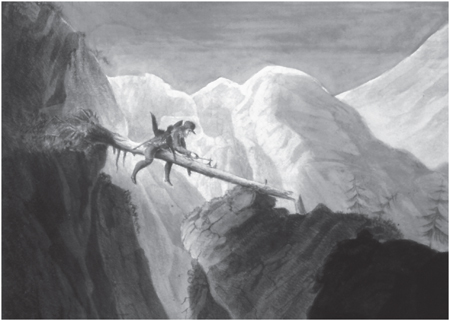

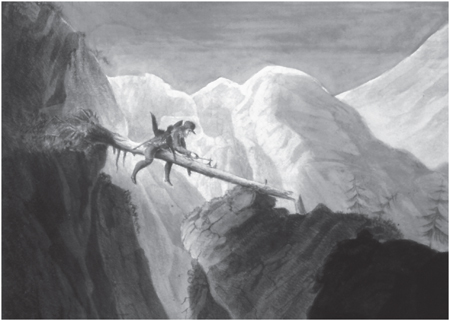

Audubon’s original watercolor painting of the Golden Eagle includes this tiny figure of a hunter crossing a chasm on a log. Many believe it is a miniature self-portrait reflecting Audubon’s own struggle to track down birds and complete The Birds of America

CHAPTER TWO

AUDUBON ON THE IVORY-BILLED FRONTIER

He neglects his material interests and is forever wasting his time hunting, drawing and stuffing birds, and playing the fiddle. We fear he will never be fit for any practical purpose on the face of the Earth.

—John James Audubon’s brother-in-law

Southern Rivers and States—1820–1835

On October 12, 1820, thirty-five-year-old John James Audubon pushed his flowing, shoulder-length hair back from his face, kissed his wife, Lucy, and their two young sons goodbye, and climbed aboard a flatboat bound for New Orleans from Cincinnati. His worldly possessions included his gun, his drawing supplies, a roll of wire, a few books, a brass telescope, and the buckskin clothes on his back. His lone companion was thirteen-year-old Joseph Mason, a boy with a genius for painting flowering plants and trees, perfect for the backgrounds Audubon would need to complete his great project.

The white area shows the wide expanse of the Ivory-bill’s original distribution. The bird might have been found within this area—although only in places where the habitat was suitable—but not outside it

Audubon didn’t even have enough money to book passage. He signed on as a hunter whose job would be to shoot game to feed the crew and passengers. But as they pushed off down the Ohio River, Audubon must have felt like a rich man, for he was finally following his dream. He was fed up with teaching dancing and giving drawing instructions to students with modest talents; he was tired of being a shopkeeper. Now he was determined to do what he cared about most: paint birds. Not just a few species, either, but all the birds of America.

As a free-spirited boy in the French countryside, Audubon had filled his room with nests and birds’ eggs and animal skins, which he practiced drawing over and over. His father sent him to America in 1803 to take care of property he had recently bought there, and to avoid having his son serve in Napoleon’s army. Arriving in Pennsylvania at the age of eighteen, Audubon was only about ten years younger than the United States of America itself.

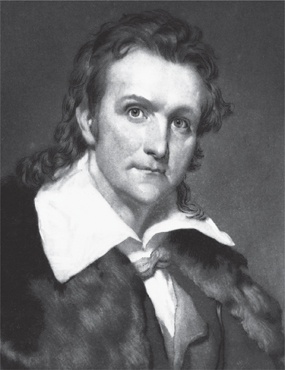

John James Audubon, engraving by John Sartain, based on a painting by F. Cruikshanks

France was settled, but America seemed new, vast, and barely explored. After Audubon married Lucy Bakewell, in 1808, the couple opened a store with a third partner in the Ohio River town of Louisville, Kentucky, selling goods to settlers and frontier families. But life behind a counter didn’t suit Audubon. He loved to roam the woods, sleeping on the ground in Indian camps. He scrapped his frilly white shirts and black satin breeches for shirts and leggings fashioned of deerskin. His leather belt held a sheath knife and a tomahawk. He sometimes slicked his long hair with bear grease. He played his fiddle and danced, and charmed nearly everyone he met. But despite his optimistic nature, he couldn’t seem to figure out a way to earn a living that would make him happy.

Audubon’s life changed one day in March 1810 when Alexander Wilson, the renowned bird artist, turned up at the store. Wilson proudly untied a folio of his bird paintings, laying them out for Audubon to see. To Wilson’s astonishment, Audubon pulled out bird paintings of his own, and as they compared the two sets of images, both men may have instantly recognized that Audubon’s were better. Wilson’s birds looked stiff, because they had been painted mainly from stuffed specimens. Already Audubon was developing an entirely different style. He had signed even his first sketches “Drawn from nature by J. J. Audubon.” The encounter with Wilson planted the seed that would form Audubon’s own future: he, too, would paint the birds of the new country, but he would paint his in natural poses, using all the extravagant colors of their feathering, showing them doing the things birds actually did, like fashioning nests and tearing at prey. He would paint them in natural settings so that he could reveal not only how the birds behaved but what America looked like.

“WOULD THAT I COULD”

Few who read Audubon’s forbidding description of Ivory-bill country made quick plans to visit. He wrote:

I wish, kind reader, it were in my power to present to your mind’s eye the favorite resort of the Ivory-billed woodpecker. Would that I could describe the extent of those deep morasses, spreading their sturdy moss-covered branches, as if to admonish intruding man to pause and reflect on the many difficulties which he must encounter …

Here and there, as [the adventurer] approaches an opening that proves merely a lake of black muddy water, his ear is assailed by the dismal croaking of innumerable frogs, the hissing of serpents, or the bellowing of alligators!

Would that I could give you an idea of the sultry pestiferous atmosphere that nearly suffocates the intruder in the meridian heat of our dogdays in those gloomy and horrible swamps!

So it was that ten years later, in the fall of 1820, after a disastrous few years in which he lost his business, had to declare bankruptcy, and even spent a few weeks in prison, Audubon decided he could wait no longer. Like Wilson, he would paint the birds of America and publish the art in a collection of volumes. Lucy supported this plan and agreed to raise their sons alone during his absence. Together with his young apprentice, Mason, Audubon spent sixteen months searching the wilderness for birds and traveling the Ohio and Mississippi rivers. Audubon and Mason often jumped off the boat and went out to shoot birds in the swamps and forests and marshes along the slow-moving Ohio, collecting the specimens that Audubon would later paint. Often they slept wrapped in buffalo robes and went long periods without eating.

As they floated down the Ohio, they heard a few Ivory-billed Woodpeckers calling from the adjacent trees, but once the Ohio joined the Mississippi River at Cairo, Illinois, forming a mighty current that swept them south toward the Gulf of Mexico at four miles an hour, the Ivory-bill’s pait pait pait, as Audubon described it, was almost constantly audible from the distant forests on either side.

On December 20, 1820, they gunned down an Ivory-bill in a swamp forest near the junction of the Arkansas and Mississippi rivers. Though its wing was broken, it tried to survive, playing dead at the base of a tree until the approaching footsteps drew too near. Then “it Jumped up and climbed a tree fast as a squirel to the very top … Joseph [Mason] came and saw it—Shot at it and brought him down.” It was the first of several Ivory-bills they would kill that winter. Audubon admired the bird’s magnificent spirit even as it was dying: “They sometimes cling to the bark with their claws so firmly, as to remain cramped to the spot for several hours after death.”

JOSEPH MASON

Before he took off to roam the land, Audubon taught French and painting to boys at a Cincinnati school he established. One who answered Audubon’s advertisement for students was a widower, the father of a boy who seemed to like to draw. The boy, Joseph Mason, enrolled in Audubon’s classes, and soon astonished Audubon by his ability to draw plants—exactly what Audubon needed. He made a deal with Joseph’s father. If Joseph could travel with him for a year, Audubon would give him painting lessons.

Before long, Audubon wrote to his wife that Joseph “now draws Flowers better than any man probably in America, thou Knowest I do not flatter young artists much. I never said this to him, but I think so.” Joseph Mason painted the backgrounds to fifty of the bird portraits in Audubon’s famous series The Birds of America.

Later, Audubon withdrew three Ivory-bill specimens from his bag—an adult male, an adult female, and a juvenile male—combed their feathers, and attached thin wires to their wings and limbs. Like a puppeteer he pulled the feathers and toes into dramatic positions that would illustrate the character of these birds. This made them look much more lively and revealing than the stiff poses Alexander Wilson had painted. By manipulating the birds, Audubon could show them in flight, or feeding young, or fluffing up their feathers—whatever seemed most natural. To make sure he got the proportions right, he placed each bird against a wire grid of tiny squares and drew his first sketches on grid paper that had squares of corresponding size. Audubon made three drawings and paintings of the Ivory-bill. The one that became best known showed three woodpeckers vigorously stripping the bark from a dead cypress tree in search of food. As Audubon sketched and painted his specimens and wrote detailed descriptions of the magnificent birds, he seemed to be worrying about the species. Was it doomed? He had seen settlers clear the frontier forests of the Alleghenies and the Ohio Valley, and he must have known that southern trees couldn’t be far behind. Of more pressing concern, the Ivory-bill’s appearance and behavior made it attractive to hunters and easy to find. Audubon wrote:

[Their calls] are heard so frequently that … the bird spends few minutes a day without uttering them; and this circumstance leads to its destruction … not because this species is a destroyer of trees but more because it is a beautiful bird, and its rich scalp attached to the upper mandible forms an ornament for the war-dress of most of our Indians, or for the shot-pouch of our squatters and hunters, by all of whom the bird is shot merely for that purpose.

Something about the bill’s whiteness made it seem magical to whites and Indians alike. Some Native Americans thought possessing it gave them the bird’s mighty power. Mark Catesby, a British naturalist who explored the American South between 1712 and 1725, saw warriors wearing headdresses of white bills strung with “the points outward.” The heads were prized objects of trade. “Northern Indians,” Catesby wrote, “having none of these birds in their own country, purchase them of the Southern People at the price of two, and sometimes three Buck-skins a bill.” Other warriors carried crushed Ivory-bill heads inside their sacred bundles, hoping to inherit the bird’s power to drill holes through their enemies. Indians buried the bills with warriors in grave mounds as far away as Colorado—hundreds of miles from the closest Ivory-bill forest.

Audubon also saw “entire belts of Indian chiefs closely ornamented with the tufts and bills of this species.” But it wasn’t just Indians; everyone wanted the heads and bills. Audubon wrote that frontiersmen were always waiting at steamboat landings, dangling two or three Ivory-bill heads out to disembarking passengers and asking a quarter dollar per head. Some fastened gold chains to the head and upper bill, making watch fobs. Even in European cities, merchants sold dried Ivory-bill skins.

Audubon was clearly concerned about the Ivory-bill’s fate, but in the early nineteenth century it was impossible to know for sure how many Ivory-bills were left, or whether the species was in danger of disappearing. During Audubon’s lifetime the country was too vast and travel too slow for anyone to keep track of how an entire species was faring. Many bird species hadn’t even been named yet, and some had not yet been discovered. There was still a great deal of territory for bird-finders to cover, especially since the area of the United States had doubled in size just a few years before, when President Thomas Jefferson made the Louisiana Purchase from cash-starved France in 1803.

It was even harder to know the status of a species that lived in more than one country, especially countries separated by water. For while there were also Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in Cuba at the time, hardly anyone in the United States knew it. There would be no mention of the Cuban Ivory-bill in Cuban scientific literature until decades after Audubon’s paintings.

SAMPLING THE BIRDS OF AMERICA

For Audubon, knowing a bird often included knowing how it tasted. The Horned Grebe, he said, was fishy, rancid, and fat. The Redwinged Blackbird and the Hermit Thrush were “delicate.” The Common Flicker tasted like ants. Bald Eagles reminded him of veal. He didn’t describe the taste of an Ivory-billed Woodpecker, though it wouldn’t be surprising if he had tried at least one.

Audubon’s most famous portrait of the Ivory-bill shows a small family hard at work. The three woodpeckers are charged with energy, sending chips flying through the air, and you can feel the insects beneath the bark scrambling for their lives. The painting captures the spirit of the lordly bird, and shows the respect Audubon had for the Ivory-bill. He may not have been able to count them all, but as he carefully painted his specimens, transferring their colors and lines to paper, he might well have been wondering how long such striking creatures could stay aboard the ark.

The Ivory-bill was so wildly, stunningly beautiful that everywhere Audubon went people seemed to want to give it a distinctive name. Audubon himself called it “the Van Dyke” because its brilliant coloring and bold stripes reminded him of the style of the Flemish portrait artist Anthony Van Dyck. It was “White-back” in northern Florida, “Pate” in western Florida, “Poule de bois” in French southern Louisiana, and “Kent” in northern Louisiana. Seminole Indians called it “Tit-ka.” But the most telling nickname of all came from an expression of awe, an exclamation uttered by those who suddenly caught sight of an arrow-like form ripping through the highest leaves of a deep forest, unfolding its three-foot-wide wings to the size of a flag, and then finally swooping straight up to sink its mighty claws into the thick trunk of a cypress tree. At such moments, sometimes all a dumbstruck witness could say was “Lord God, what a bird!”

Audubon’s painting of the Ivory-bill in The Birds of America