Jim Tanner’s 1931 Model A Ford coupe

CHAPTER NINE

WANTED: AMERICA’S RAREST BIRD

Saw old sign[s of woodpeckers], lots of almost impenetrable vines, and no Ivorybills.

—A common entry in James Tanner’s journal

Riverbottom Swamps of the Southeastern United States—1937–1939

John Baker was a man who knew how to get what he wanted. He had never backed down as a fighter pilot in World War I, and afterward, as an investment banker, he had developed a well-earned reputation as a hard negotiator. But this tough man loved birds, so when he was offered the chance to direct the Audubon Society in 1934, he walked away from banking without even a glance back at Wall Street. He immediately recruited an all-star team of young scientists, bird experts, and teachers, including Roger Tory Peterson, the remarkable young artist and educator whose new Field Guide to the Birds was creating thousands of new bird-watchers overnight. Baker set out to broaden the Audubon Society’s mission so that it conserved not only birds but also water, soil, plants, and other wildlife—whole ecosystems. As Baker put it, “Every plant and animal has its role to play in the community of living things. There is no such thing as a harmful species; all are beneficial.”

When Baker found out that a few Ivory-billed Woodpeckers were by some miracle still alive in Louisiana, he made up his mind to save the species. It was one thing to let a creature slip away without knowing it, but the Cornell films and recordings proved there was still hope. Like Doc Allen, Baker was convinced that the key to the Ivory-bill’s survival was knowing more about it. He quickly raised thousands of dollars for an “Audubon Research Fellowship” that would fund an expert to spend three years studying the Ivory-bill under Doc Allen’s supervision at Cornell. Among other things, this expert would try to locate every Ivory-billed Woodpecker left in the United States. After carefully studying the bird’s biology, health, and history, the expert would write an action plan for saving the species—like a doctor writing a prescription for a feathered patient. It would be the most detailed conservation plan ever attempted in the United States for a single bird species.

At Cornell, once again Doc knew exactly who he wanted. But this time Jim Tanner’s commitment to the Ivory-bill would have to go much deeper. Always on the move, he would have to track the bird through wild haunts like a sheriff pursuing a fugitive. For years he would have no permanent address.

Doc explained the hardships to Tanner. A normal life with friends and family would be impossible. He would usually be beyond the reach of telephone or telegram, and he would have to solve his own problems. Three years was a long time. It could get lonely.

But to Jim Tanner, all this weighed less than a feather compared to the rewards of such a chance. He could learn so much of what he hungered to understand. He could contribute to the science of ornithology. His work would count toward a doctoral degree, and then maybe help him establish a teaching career. Best of all, maybe he could help save a magnificent bird that he had grown to love. He was twenty-three and unmarried, and he even had a car: a 1931 Model A Ford coupe that was as tough as a small truck. Tanner didn’t even hesitate: Doc had his expert.

At Cornell, Doc and Tanner carefully developed the goals of the investigation:

1. Tanner would try to find out where Ivory-bills had lived historically—all the places they had ever been found. That meant a huge amount of reading, writing to experts, visiting libraries and museums, talking to old-timers with long memories, and listing and mapping every report ever written down by anyone who had collected an Ivory-bill specimen.

2. He would also try to discover where Ivory-bills lived now. He would visit every major swamp and cypress forest from North Carolina to Texas if he had to. He would interview hunters and foresters, game wardens and bird-watchers, and try to find every Ivory-bill still alive. He would make a list and a map showing where they were. By comparing the current map to the historical map, he could show how much of their habitat had been lost and what their favorite types of forest had been.

3. He would study the ecology of the species—the relationship between the Ivory-bill and its environment. What did it eat? How did it find its food? Did anything eat it? Mites? Mosquitoes? Owls? If it couldn’t find its favorite food, what else would it eat, if anything? Did it need certain kinds of trees for food and shelter?

ECOLOGY

In the 1930s and 1940s, ornithologists became more and more interested in ecology—studying a bird’s whole natural environment and how it interacted with everything around it—not just in the biology of an individual species. James Tanner was an ideal candidate to study the Ivory-bill because his interests were very broad; he knew that in order to learn how to save the Ivory-bill, he had to know how the whole forest worked.

Those who study natural ecosystems learn that humans simplify and nature complicates. For example, a tree plantation has fewer species of plants and animals living in it than the forest it replaced. The original forest had more ecological “niches”—the small environments in which species evolve ways to find food, protect their young, and stay safe from predators. A big, ragged forest ecosystem like the Singer forest had thousands of niches, many more than the farms and settlements in the surrounding cleared areas.

4. He would investigate the bird’s reproductive and nesting habits. What kinds of trees will an Ivory-bill nest in? How high off the ground are the nests? How many eggs does it lay? If one clutch of eggs fails, will it produce another in the same year? If so, how many times? How much food does a nesting family need, and how much space is needed to provide it? Do both parents always incubate eggs and feed young? And, of course, he would try to answer the question that so plagued Doc—why were the nests failing to produce surviving young at the Singer Tract?

5. Finally, Tanner would create a plan to protect the Ivory-billed Woodpecker. This would be a detailed blueprint that conservationists could use.

Tanner prepared carefully for his new life. He bought dozens of one-cent postcards to send to Doc, Baker, and his friends and family while he was on the road. He figured out how to unbolt the front seat from his car, lift it out, and turn it into a bed that could be laid on the ground. That would save time and money, and would let him sleep in the woods if he needed to. He packed maps, tools, books, binoculars, boots, a first-aid kit, clothing, and camping gear. He made address lists of Doc’s contacts and carefully tucked away the letter of introduction Doc wrote for him to show to strangers. It read:

To whom it may concern: You will find Mr. Tanner extremely reliable and trustworthy, and if you prefer that your information should get no further than him, I know that he can keep a secret when it concerns the welfare of the Ivory-bill. —Arthur A. Allen

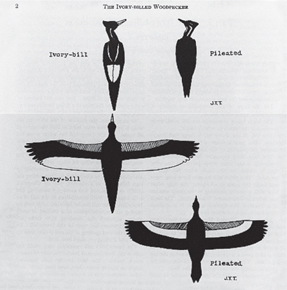

Tanner found drawings of a Pileated and an Ivory-billed Woodpecker shown side by side. A printer shrank the page to pocket size and ran off dozens of copies for him. These cards would be valuable, since the two species were so often confused. They would also give him something to leave with the many people he would interview—it was half business card, half wanted poster.

IVORY-BILL ALIASES

James Tanner made this list of the names that the Ivory-bill was called in scientific literature or by people he met:

Pearly Bill

Pearl Bill

Log-god

Log-cock

Woodcock

King Woodchuck

King of the Woodpeckers

Indian Hen

Southern Giant Woodpecker

Pate or Pait

Ivory-billed Caip

Tit-ka (Seminole name)

Grand Pic Noir a bec blanc

Poule de bois [in southern Louisiana]

Grand pique-bois [in southern Louisiana]

Habenspecht

Elfenbeinschnabel-Specht

Kent [northern Louisiana]

He celebrated the holidays with his parents in Cortland and on January 4, 1937, took off in his roadster, passing through the low hills he had hiked as a boy, over the Catskills, down to New York City, and on toward the South. His car had no radio and he wasn’t much of a singer; his dreams were his entertainment. He was off to do what no one had ever done, and it happened to be the thing he wanted to do most. He would do his best to find all remaining Ivory-bills, to understand them, and to help them. As he motored toward the great southern river swamps, he could have titled his journey “Wanted: America’s Rarest Bird.”

THE ADAPTABLE RESEARCHER

On January 20, 1937, Jim Tanner followed a hand-sketched map to a dirt road which led to a landing along the Altamaha River in southern Georgia. The Ford pitched to a stop around noon. Tanner got out and stretched. The day was fine and warm. An old-timer was fishing from a crude wooden rowboat just offshore, and they fell into pleasant conversation. A few minutes and four dollars later, the boat was Jim Tanner’s. Tanner piled in the gear he needed, pulled the car off the road, and shoved off downstream.

He had come to the Altamaha River to check out an Ivory-bill record that was now eleven years old. Somewhere in his research he had seen a report that in 1926 a man named Verster Brown Sr. had spotted an Ivory-bill in a swamp on the river near Baxley, Georgia. The details of his sighting were good enough to make it seem worth exploring. Tanner stayed on the river for the next five days, paddling fifty miles in all. Often he would raise the oars out of the water and cock his ear for the Ivory-bill’s cry. He never heard it. Most of the trees along the river had been recently cut, and there wasn’t much wildlife of any kind to be seen or heard. Local people had little useful information. Finally he dragged the boat up to the shore and hitchhiked back to his car. “It did not produce results,” he wrote in his journal, “but it was a grand trip on a pretty river.”

Drawings by James Tanner

IVORY-BILLS VERSUS PILEATEDS

Tanner believed that most people who told him about Ivory-bills were really reporting the much more common Pileated Woodpecker. Both birds are very big and both have black-and-white coloring. Males of both species have red crests, adding to the confusion.

Tanner wrote, “The position of the white on the wing is by far the most reliable field character at all times,” he wrote. “In the Ivory-bill the white is on the rear half of the wing and is visible on the back when the bird is perched and its wings folded. In the Pileated the white is on the front half of the wing and is hidden when the wings are folded.”

He drove south to Florida, the state with more records of Ivory-bill sightings than any other. Pulling the drawing of two woodpeckers from his shirt pocket, he introduced himself to dozens of loggers, hunters, trappers, poachers, and wildlife managers. They gave him still more names of old-timers who knew the land. He dutifully looked most of them up. But everywhere the story was the same—yes, Ivory-bills, or Logcocks, or Lord God birds, had been here, but not for a while. The rumors were thick as mosquitoes, and like mosquitoes, rumors seemed to breed more rumors.

Early in February, Tanner reached the Everglades. Sunburned game wardens with leathery faces squinted at him, stroked their chins, and said yes, they thought perhaps they had seen the birds among the cypress trees maybe fifteen or twenty years ago. One guide, Dewey Brown, said he had heard Ivory-bills calling recently from Big Cypress Swamp. He was happy to show Tanner the spot, but said it would take a few days to get there. By now, Tanner was learning to size up exactly how much of his time any particular rumor was worth. This one was promising, but not that promising. “I told him I would return next year with more time for a decent trip,” Tanner noted.

Tanner’s final Florida destination was the Suwannee River, a spot famous for Ivory-bills. William Brewster and Frank Chapman had floated down this river in 1890, killing one Ivory-bill and hearing another. Two years later, Arthur Wayne and his “crackers” had shot Ivory-bills for Brewster and others. Now, more than forty years later, a few of the men who had collected for Wayne were still alive. They were wrinkled old woodsmen with long memories. As Tanner later wrote, they said that “after Wayne’s work there Ivory-bills were very unusual and that he had secured almost all of them.” Looking around at the grand trees lining the banks, Tanner hoped it wasn’t true. He thought the Suwannee still looked good enough to investigate.

Tanner’s map showed a landing, a few miles downstream from Old Town, where the road went down to the riverbank. Maybe he could find another boat or canoe there. For the next hour, Tanner guided the Ford on a jolting, head-bumping ride along two beaten ruts that finally ended at a deserted clearing by the river’s edge.

Tanner got out as the dust settled around him. With darkness fast approaching, he walked into the trees and loaded his arms full of twigs and limbs, then stacked them into a tidy pyramid and lit a fire. Minutes later he was contentedly crouched over his supper when he heard a truck rattling down the road. It came to a stop, and several men spilled out. Waving a hasty greeting, they hurried off to gather firewood. After a while Tanner heard bootsteps approaching his fire. Three faces appeared out of the dark, lit by the blaze. The men squatted on their heels and introduced themselves. They said they were there for some night fishing.

Many men in Tanner’s situation would have been frightened out of their wits. He was unarmed and surrounded by strangers in the middle of nowhere. Maybe they were after his car. Maybe his money. But Jim Tanner was, as Doc Allen liked to put it, “adaptable.” He could fit in anywhere.

“What are you doing here?” one of the men began. Stirring his fire, Tanner answered, “I am looking for peckerwoods.” The men were silent. He then launched into his well-rehearsed speech about how there were two kinds of big woodpeckers in these parts, one common and the other rare, and that he was trying to find the rare one. As he was speaking, Tanner could see their eyes narrowing with suspicion. Tanner rambled on until one of the men suddenly burst out laughing. The others soon followed.

When he could finally speak, the first man said, “By golly, I thought for a minute you really were hunting for a peckerwood!” Catching his breath, he explained to Tanner that in those parts “peckerwood” could mean either a bird or a woodsman. Years before, another stranger had come down to the river looking for the human kind. With revenge in his eyes, he was after someone who had crossed him and had escaped on the river. The men had assumed Tanner was after the same fugitive until they realized he actually was looking for a bird.

The strangers tromped off into the blackness to set out their fishing lines, and then banked their own fire to a roaring blaze against the cool night. They yelled over for Tanner to join their party, and he did. “We had a big meal of fried fish, baked yams, and biscuits. I ate my share even though I had already had one supper. Then they loaded their truck and near midnight disappeared up the narrow road.” It was one of many days and nights that didn’t turn out the way Tanner planned, but it showed that just about anything could, and would, happen on an expedition like this.

HARD TRAVELING

For the next three weeks Tanner drove, hiked, galloped, and waded around Florida chasing leads, scribbling notes, leaving his pictures behind, and trying not to get frustrated. The Suwannee had a promising habitat, but no Ivory-bills. The best lead yet took him to a forest near Brooksville, Florida, where an Ivory-bill had been reported only the year before. Tanner searched the area with two local men and at last found a sign: “a dead pine from which the bark had been completely scaled, apparently the work of an Ivory-bill.” Tanner assumed the bird was only passing through, though, since the habitat didn’t seem good enough for nesting birds.

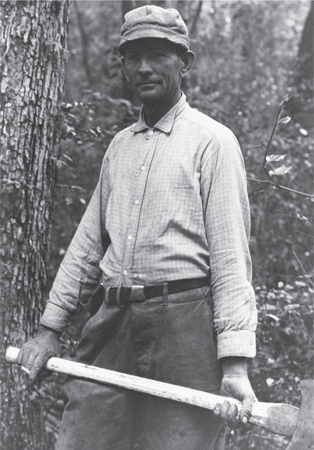

On March 17 he took off west for Louisiana and the Singer Refuge, the one place where he knew he could actually find Ivory-bills. Two items of good news awaited him: J. J. Kuhn, the woodsman who had guided the Cornell sound team so expertly before, was available and eager to help. Just as happily, Tanner and Kuhn could use the Singer Manufacturing Company’s cabin in the woods as a base of operations. That meant they could stay in the woods all the time except when they had to go into town for supplies.

J. J. Kuhn, warden of the Singer Refuge and Tanner’s indispensable companion

Tanner and Kuhn concentrated their search on the east side of the Tensas River. On March 26 they finally spotted a pair of adult Ivory-bills winging swiftly through the flooded backwater called John’s Bayou, and after four days of hard searching Tanner found their nest, chiseled in the top of a sweet gum. All day long the parents took turns shuttling long white grubs to a single open-mouthed baby, who constantly yapped for food.

The very next day, the little bird hopped up onto the lip of the nest hole, steadied itself, spread its wings, and leaped into its first flight. It never returned to the nest again, and the family’s address shifted to a tree about a quarter mile away where they slept—or “roosted”—together each night.

“[The young bird] flew well from the start,” Tanner wrote proudly. “The family hunted together close to the nest tree for the next two months. The youngster grew stronger and more independent every day. Within a month it could join its parents on food-finding trips two miles away from their home tree. By mid-July it was nearly as big as its mother and father, a powerful flyer and a mighty hunter of grubs.” It still called to be fed, though, as young birds often do. Tanner found himself delighted by the prowess of this young bird, but worried that the family had produced only one egg. “This pair of birds gave no indication of nesting a second time,” he wrote, “even though they nested so very early.”

Throughout May and June, Tanner and Kuhn combed the forest for more Ivory-bills. The daily hikes installed a mental map of the forest in Tanner’s head. He came to know where the waterways called bayous emptied into the forest, where the lakes were, and how the forest trees changed when the ground got lower or higher, wetter or drier. The Ivory-bills nested and slept in sweet-gum and oak trees that sprouted from dry ridges that had long ago been banked up by the Mississippi’s floods. Tanner called them “first bottoms.”

Kuhn and Tanner usually split up so that they could cover twice as much ground. They searched mainly in the morning, when the birds were most active. Tanner’s strategy was to stop walking and listen about every quarter mile, since the Ivory-bill’s call carried about half a mile. He always heard Ivory-bills before he saw them. When he wasn’t searching for birds, he was working on other parts of his research project, doing things like counting trees, collecting and inspecting grubs, scouting new locations, and investigating the biology and ecology of the Ivory-bill in countless other ways.

Sometimes he just sat still. As a young boy, he had practiced sitting still outdoors for long periods of time. Now this was helping him in his profession. As he sat and listened, swatting bugs, taking notes, trying not to scratch his poison ivy welts, daydreaming and dozing every now and then, he occasionally tried to imitate the Ivory-bill’s call to see if the birds would answer. They never did. Once he tooted through the mouthpiece of a saxophone. No luck. But from time to time an Ivory-bill would call on its own from somewhere way off in the forest, sending him springing to his feet and tearing off after it through the underbrush.

During the winter and spring of 1937, Tanner and Kuhn found evidence of adult Ivory-billed Woodpeckers in seven different parts of the Singer Tract. Since adult Ivory-bills mated for life and stayed together all year round, Tanner assumed there were seven different nesting pairs, even though he saw only one young bird the whole time. Another parent was seen winging across a lake with a grub dangling from its bill, which almost certainly meant there was a young bird to be fed, but they couldn’t find the nest and never saw a nestling.

Tanner kept wondering why all those adults produced so few young birds. Was Doc right about inbreeding? Were they tormented by mites? Or was it something else they hadn’t even thought of? After the small Ivory-bill family Kuhn and Tanner found on March 26 had abandoned its nest tree, Tanner shinnied high up the sweet gum and inspected the nest. Once again there was no evidence of parasites or mites, nor were there signs of struggle. The disappearing Ivory-bills were still a mystery.

When summer came, broad leaves made treetops almost impossible to see and the air filled with swarming mosquitoes. Tanner rolled up his bedroll, packed his boots, and got ready to hike out to Tallulah and head home. But just before he left, he and Kuhn heard news that hit them both hard: the Singer company had sold six thousand acres of its land to a lumber company, and logging had already started. The land was on the west side of the Tensas—not the best Ivory-bill habitat in the forest, but now the lumbermen had their feet in the door. Even worse, Singer had sold the rest of the west side to the much bigger Chicago Mill and Lumber Company—which had a major sawmill in Tallulah. Singer was even allowing an oil company to drill test wells in prime Ivory-bill habitat.

Tanner said goodbye to Kuhn on June 29 and spent another month tracking leads in Louisiana and South Carolina before he turned north toward home. Back at Cornell, he sorted through the hundreds of pages of notes he had compiled, and began to reflect on what he had learned so far.

In his first season of sleuthing, he had been able to find Ivory-bills only at the Singer Tract. There was still promising habitat at Big Cypress Swamp and the lower Suwannee River, both in Florida. These sites merited follow-up visits. Four other places looked good, too, but less so. The birds at Singer were not reproducing well, and he still didn’t know why. But he now knew more about the kinds of trees the birds liked, what they ate, and how much space a nesting family seemed to need.

Casting a shadow over everything was the sale of Ivory-bill habitat at Singer. Tanner didn’t let his emotions show easily, but there was desperation in his year-end report to John Baker of the Audubon Society. Time was running out. “Those woods should be preserved,” he wrote. “That area should be a national monument, and I strongly recommend that a movement be started towards that goal, even though the lumbering interests and possibility of oil present difficulties.”

Looking back at that winter and spring, Tanner knew there were still many more questions than answers, but one thing was certain: he had done some hard traveling. He wrote a tribute to his indestructible Ford that might well have reminded him of himself. “It has been the first car to break a way over many a muddy road,” he said. “It has had several springs broken, mufflers knocked off and running-boards knocked loose, bumpers broken on trees, and the front axle bent. But it still runs.”