When George Washington went to sleep Friday night, he was six years old.

When he woke up on Saturday, he was seven. It’s my birthday, he thought. Happy birthday to me.

George went down to breakfast. He peered out the kitchen door and checked the temperature.

“Another cold day,” he said to his mother. “But I guess there’s nothing special about that.”

“Certainly not,” she said. “Now eat your porridge and mind the baby.”

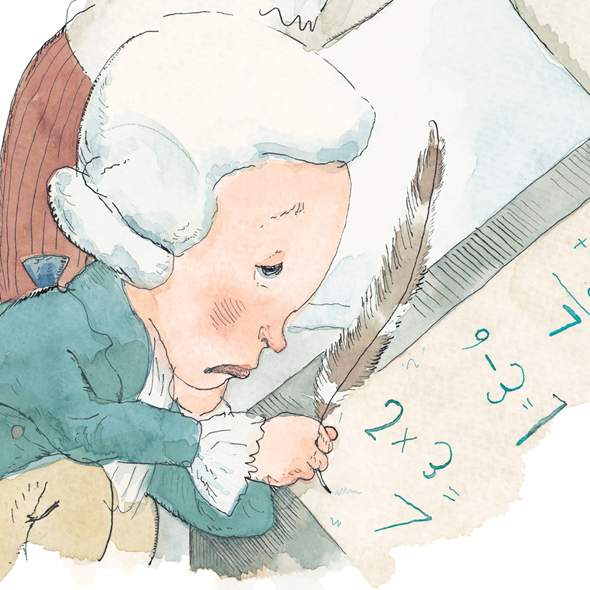

After breakfast, George went to the library for his morning lessons.

“Get to work, George,” said his half brother Augustine.

“I am working,” said George.

“And don’t blot your copybook!”

“Tyrant,” muttered George, under his breath.

George was usually very good at arithmetic. But not this morning.

Augustine marked his paper.

“All wrong,” he said with a sigh. “You’ll never amount to anything.”

“Someday I’ll be the boss of you,” said George, but he made sure his brother couldn’t hear.

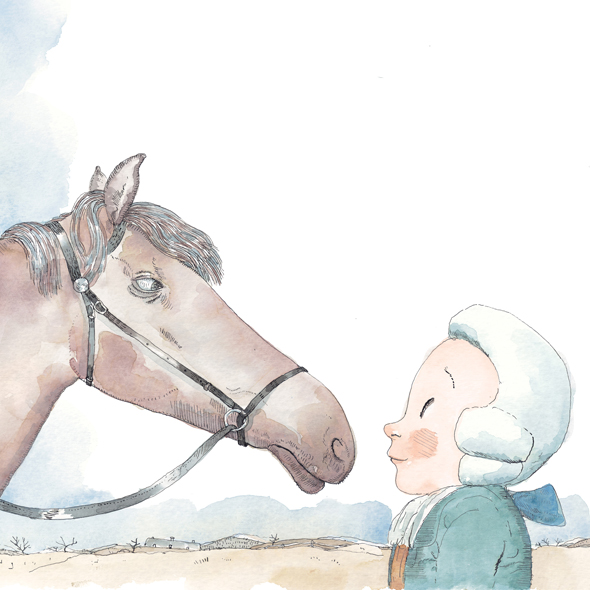

George gave up on his lessons and went outside to visit the horses. He patted his father’s old dray. She snorted at him.

“When I’m older, I’ll ride a horse even bigger than you,” said George.

He imagined what he would name his own horse when he got older.

Then George noticed how cold it was. I bet I’m turning blue, he thought.

To warm himself up, George started tossing stones into the river. “Some birthday”—toss—“this is,” George said.

A friend of his brother’s strode by. “Bet you can’t throw one of those all the way across the river,” said the young man.

“Bet I can,” said George. He screwed up his eyes and made a birthday wish. Then he leaned back, wound up, and threw the stone all the way to the other side of the Rappahannock River.

“Lordy! That’s pretty good for a six-year-old,” said the young man. And he ran off.

George was so peeved at being called a six-year-old that he tried to toss another stone across the river.

It sank before it got halfway over.

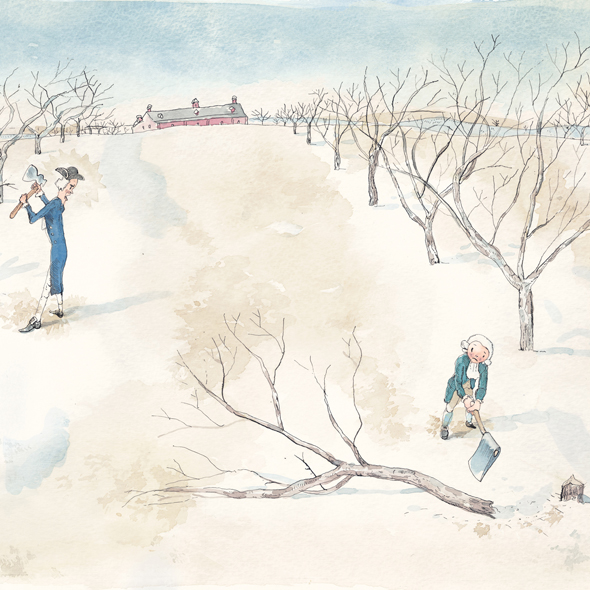

By the time he got home, George was cold and grumpy and ready for some sweet tea by the fire. He waved to his father, working in the orchard.

“Glad to see you, son,” said George’s father. “You can help me prune these cherry trees.”

“But, Papa—” George began.

“Fetch a hatchet,” said his father.

George fetched a hatchet. He hacked off old tree branches. It was hard work. His hand ached. His back was sore. This is no way to spend a birthday, thought George. I’m so mad I could just—

George’s father strode over to his son. “Who did this?” he asked, though George thought the answer must be pretty obvious.

“Don’t you know what day it is?” asked George.

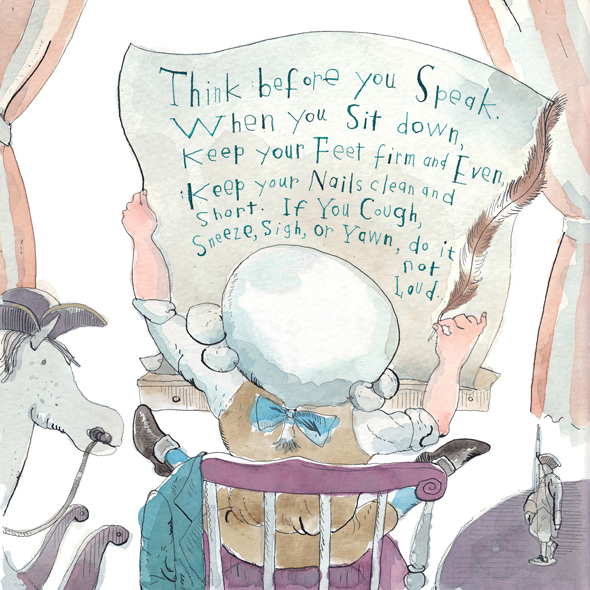

“It’s Saturday,” said his father. “And I’d advise that you think before you speak again.”

George figured he’d better confess.

“Father,” said George at last, “I cannot tell a lie. It was I who chopped down the tree.” George always used his best grammar when he was in trouble.

His father sighed. “I’m glad you told the truth, son,” he said. George started to smile.

“But I am not happy about this tree.” George stopped smiling.

“I suppose you’d better chop it up now that the damage is done,” his father said, “and put it in the woodshed to dry.”

The woodshed was across a little creek from the cherry orchard. Back and forth George carried the heavy loads of wood, crossing the icy creek each time.

“Hope I never have to do this again,” he said to himself.

At last he finished his work.

“Now clean your face and hands and powder your wig and occupy yourself gainfully until dinnertime,” said his father.

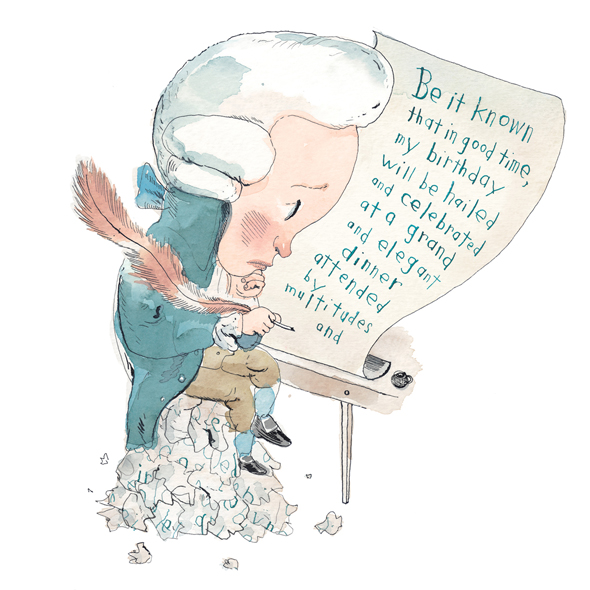

George went to his room. He got out a piece of paper and started writing.

But George wasn’t sure this was what his father would call gainful occupation.

So he thought and he thought, and he came up with some other ideas, ideas he believed his father would like.

He worked so hard on his list that he did not hear the bell for dinner.

“George!” called his mother. “Get down here at once.”

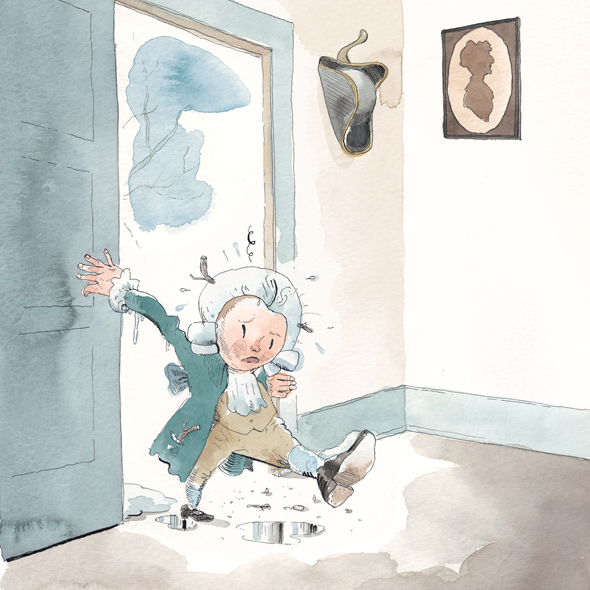

George hurried down the stairs.

When he opened the door to the dining room, he got a mighty surprise.

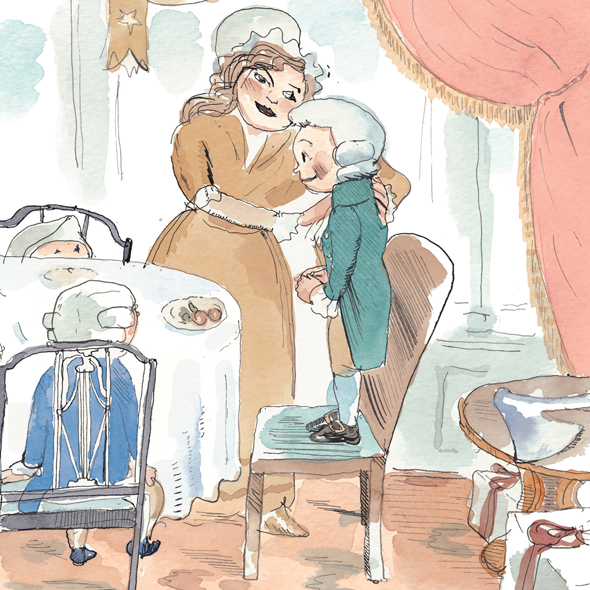

“Happy birthday, George!” said his family.

The family sat down to dinner and had a grand feast in honor of the birthday boy.

“I thought you had all forgotten,” said George.

His mother gave him a squeeze. “How could anyone forget your birthday, George Washington?” she said.

“Oh, Mama,” said George. “You only say that because you’re my mother.”

But to tell the truth, nobody did forget George Washington’s birthday ever again.