VI. Six Years of Anti-Piracy and Broader PLAN Growth

China’s naval anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden provide the first major insights concerning China’s approach to protracted Far Seas operations. The PLAN has discovered over the past half-decade that the most important lesson instilled through anti-piracy is the value of real experience. That is, China’s Navy must learn by doing, and the insights it has gained from the Gulf of Aden mission would not have been available elsewhere. Broadly speaking, several major breakthroughs help explain why the PLAN initially undertook and continues to conduct anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden:

1. Creativity and inter-agency cooperation

2. Incorporating advanced equipment

3. Cultivating experienced personnel

4. Military diplomacy

Major changes in the organizational structure of China’s armed forces are reflective of the ascendance of China’s Navy as a pillar of national security, in both Near and Far Seas. In order to place these changes in context, this section will begin with an overview of military reform plans under Xi.

•

Military Reform in the Xi Era

The Gulf of Aden deployment is particularly interesting in the context of Chinese military and security reforms under Xi Jinping and China’s new cohort of civilian and military leaders. While the precise outcome of these reforms is not yet clear in the public domain, it seems plausible that the PLAN will carry on the legacies of Jiang and Hu by further broadening its mission scope under the leadership of Xi. China’s new leadership has, in its first three years, demonstrated an active interest in reforming Chinese security institutions that have important implication for Chinese naval development. While most accounts are highly speculative, Xi purportedly enjoys considerable legitimacy and acceptance among elite Chinese leaders.

Given Xi’s apparently tight grip on the Party and military, it is possible that he may be planning to issue broad, doctrinal military guidance that would deeply impact the PLAN’s development trajectory. Xi has not yet issued any specific guidance on this scale, but he likely has another seven years until his term ends in 2022 with the closing of the 20th Party Congress. However, for now specific guidance that would substantively alter the growing role of the PLAN in global maritime security, such as anti-piracy operations, seems unlikely to emerge, and China’s naval role in global nontraditional missions is likely to continue its gradual increase under the new leadership.104

Xi has already made it abundantly clear that his administration is placing more emphasis on preparing to be able to fight and win wars. His policies are highly focused and apparently emphasize meeting specific objectives cost-effectively. It is thus possible that Xi may place more direct focus on “traditional” capabilities such as state-to-state war fighting, which could result in a de-prioritization of anti-piracy and other nontraditional maritime security activities. Arguably, the ambivalence of China’s response to disaster relief in the Philippines following Typhoon Haiyan in late 2013 is an early sign of the PLA/PLAN’s “reading the tea leaves” in this regard. However, a more nuanced approach could emerge if Xi and his comrades seek to balance more active traditional military policies in the Near Seas that harm China’s international image with an increase in goodwill missions in the Far Seas.105 Moreover, growing Chinese resources and capacity may convince that China can “do more of everything,” including anti-piracy-type missions.

Signs are beginning to emerge that China’s military will undergo major organizational changes under Xi. It was reported in late December 2013 that China is planning to condense the PLA’s seven ground force-dominated military regions into five integrated regions.106 To date, Chinese official media sources, such as Liberation Army Daily, have responded by labeling rumors of military region reform as “pure guesses,” though no outright denial of the rumors has occurred. On January 3, 2014, a Xinhua article confirmed that the PLA would establish a joint operational command system “in due course,” designed to increase overall mobility and integration between China’s armed forces.107 Shortly after, however, the China News Agency reported that the Information Affairs Office of the MND had stated that rumors on restructuring the PLA command system were “groundless.”108 It seems most likely that reforms are under way, as mandated by Party decisions, but that details of implementation remain under negotiation, particularly controversial for a PLA almost certainly facing a significant wave of ground force downsizing, which would include significant reductions in senior officer billets. The Pentagon’s 2015 report on China’s military judges that reforms likely under consideration include reducing non-combat forces and the relative proportion of ground forces; elevating the proportion and roles of enlisted personnel and non-commissioned officers vis-à-vis commissioned officers; bolstering “new-type combat forces” for naval aviation, cyber and special operations; establishing a theater joint command system; and reducing China’s current seven Military Regions by as many as two.109

If the said reforms were implemented, new regions would reportedly house a joint operations command mechanism to integrate PLA, PLAN, PLAAF and PLASAF resources and activities, reflecting China’s quest for a military better suited to address a range of modern traditional and nontraditional security threats. As a result of the reform, the boundaries of existing PLA military regions could be redrawn. They would likely be reduced in number, and two coastal regions might be created with far greater navy and even air force representation in their leadership. This is significant for the PLAN, which no longer has support bases (baozhang jidi) other than for aircraft carriers in the North Sea Fleet (NSF) and South Sea Fleet (SSF).110 The overarching result would be a heightened role for the PLAN in national security. As Li Qinggong, Deputy Secretary-General of the China Council for National Security Policy Studies, articulated, “China has built an iron bastion in its border regions. The major concern lies at sea.”111 If and when such consolidation actually occurs, the PLAN and PLAAF will be the clear “winners,” and are poised to assume more central roles in maritime-oriented military regions. Indeed, the latest edition of the doctrinal handbook Science of Military Strategy suggests that the PLAN is gradually moving from a three-fleet configuration toward a “two ocean” (

![]() ) orientation.112

) orientation.112

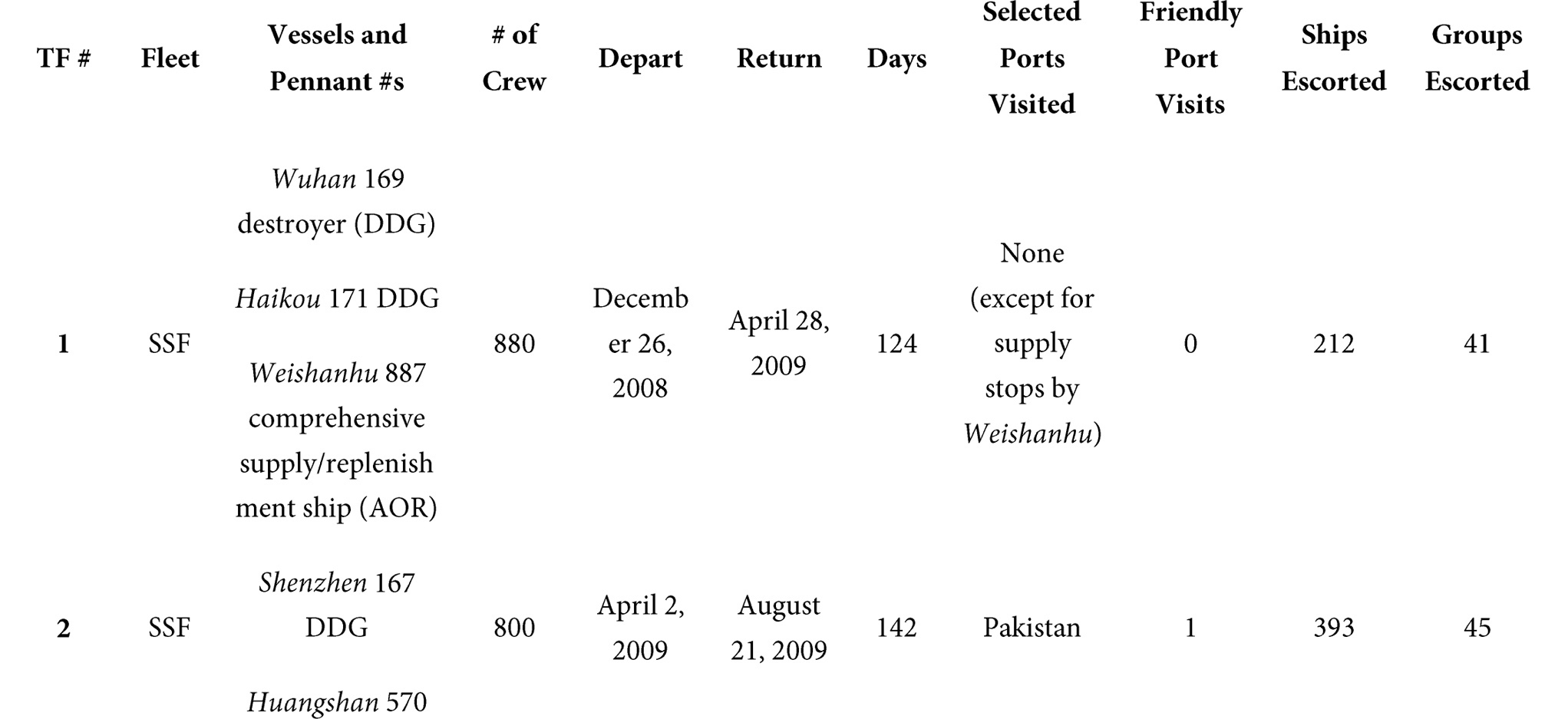

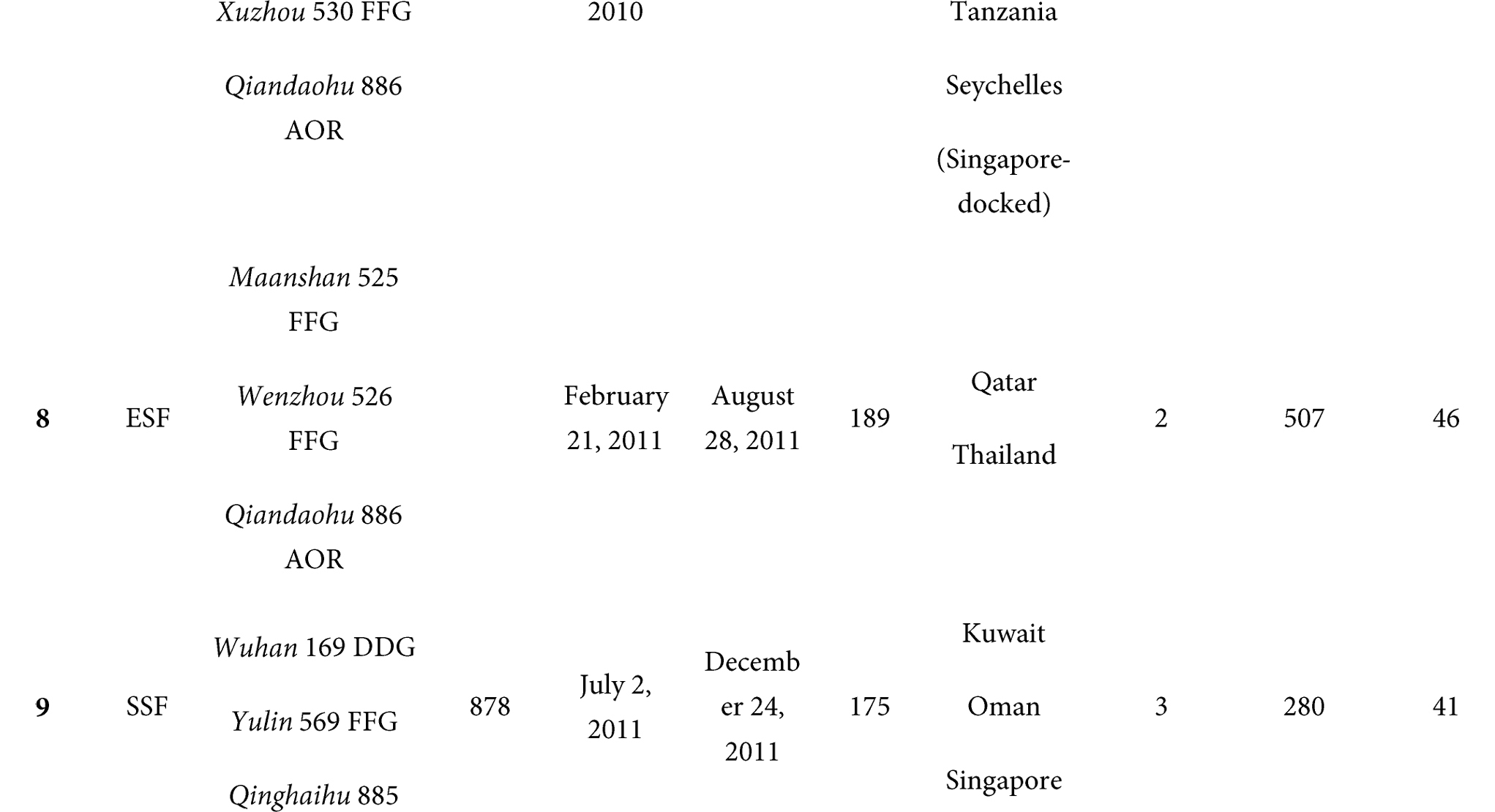

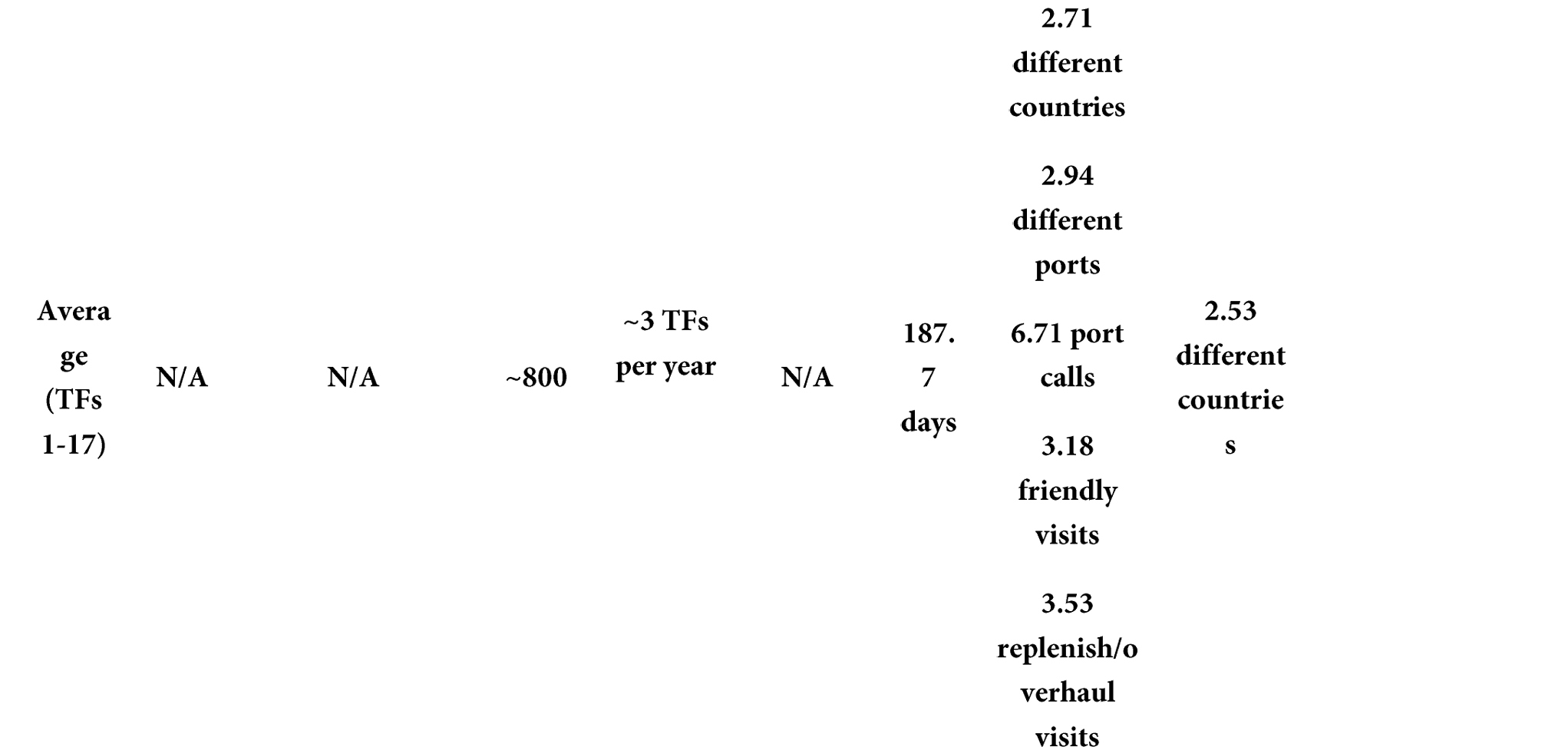

Regardless of future trajectories, the PLAN has amassed a considerable portfolio of anti-piracy activities since December 2008. Exhibit 1 organizes the statistical achievements of each escort flotilla through January 2014.

EXHIBIT 1: PLAN Gulf of Aden Escort Statistics by Task Force (TF), 2008-15

»7 joint

drills

Note: Duration of TFs is based on date leaving and returning to port in China; exact dates for escort responsibilities in Gulf of Aden are not available systematically. Duration calculated using http://www.timeanddate.com/date/duration.html, with final day included. Activities by other non-TF vessels supporting mission (e.g., submarines) not included. Numbers of friendly visits, replenish/overhaul visits, and joint drills total more than port calls because some port calls include multiple events. Number of port calls and related events, etc., may not be completely accurate or comprehensive. Replenishment/overhaul cases are particularly easy to miss since they are not always reported at the same levels of frequency and clarity as friendly visits. Summary statistics calculated exclude data from 19th and 20th TFs.

Exhibit 1 Sources:

Overall: Kenneth Allen, “PLA Foreign Relations under Xi Jinping: Continuity and/or Change?” paper presented at the CAPS-RAND-NDU 26th Annual PLA Conference, RAND Corp., Arlington, VA, November 21-22, 2014. TFs 1-8: “

![]() ” [A Brief Introduction to China’s Ten Naval Escort Task Forces], Xinhua, December 26, 2011, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2011-12/26/c_122483096.htm; “

” [A Brief Introduction to China’s Ten Naval Escort Task Forces], Xinhua, December 26, 2011, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2011-12/26/c_122483096.htm; “

![]() ” [Third Chinese Navy Escort Task Force Sets Sail for Somali Waters],

” [Third Chinese Navy Escort Task Force Sets Sail for Somali Waters],

![]() [Phoenix News] July 16, 2009, http://news.ifeng.eom/mil/2/200907/0716_340_1252031.shtml. TF 9:

[Phoenix News] July 16, 2009, http://news.ifeng.eom/mil/2/200907/0716_340_1252031.shtml. TF 9:

![]() [Guo Dan],

[Guo Dan],

![]() [Li De] and

[Li De] and

![]() [Xiao Delun], “

[Xiao Delun], “

![]() ” [9th Naval Escort Taskforce Triumphs],

” [9th Naval Escort Taskforce Triumphs],

![]() [Zhanjiang Daily], December 25, 2011, http://www.gdzjdaily.com.cn/zjnews/zjpolitics/2011-12/25/content_1435956.htm. TF 10: Gao Yi and Tang Zhuoxiong, “10th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns to Base,” Liberation Army Daily, May 8, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7810913.html. TF 11: “Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Ensures Safety for 4,640 Ships,” Naval Today, May 14, 2012, http://navaltoday.com/2012/05/14/chinese-naval-escort-taskforce-ensures-safety-for-4-640-ships/; Chen Dianhong and Mi Jinguo, “11th Chinese Naval Task Force Returns Home After Visiting Israel,” Liberation Army Daily, August 21, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7918352.html; “11th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Leaves Gulf of Aden,” Liberation Army Daily, July 25, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7886530.html;

[Zhanjiang Daily], December 25, 2011, http://www.gdzjdaily.com.cn/zjnews/zjpolitics/2011-12/25/content_1435956.htm. TF 10: Gao Yi and Tang Zhuoxiong, “10th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns to Base,” Liberation Army Daily, May 8, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7810913.html. TF 11: “Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Ensures Safety for 4,640 Ships,” Naval Today, May 14, 2012, http://navaltoday.com/2012/05/14/chinese-naval-escort-taskforce-ensures-safety-for-4-640-ships/; Chen Dianhong and Mi Jinguo, “11th Chinese Naval Task Force Returns Home After Visiting Israel,” Liberation Army Daily, August 21, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7918352.html; “11th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Leaves Gulf of Aden,” Liberation Army Daily, July 25, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/7886530.html;

![]() [11th Escort Taskforce Returns to the Embrace of the Mother Country], Qingdao Finance Daily, 6 September 2012, http://qd.wenming.cn/syjj/201209/t20120906_345091.html. TF 12: Cheng Bijie and Hou Rui, “12th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns Home After Visiting Vietnam,” China Military Online, January 15, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8092041.html; Cheng Bijie and Hou Rui, “12th and 13th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission Handover,” China Military Online, November 23, 2012, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2012-ll/23/content_5109609.htm; 12th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns Home,” China Military Online, January 22, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8101766.html. TF 13: Zhu Shaobin and Xiao Jiancheng, “13th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Arrives in Gulf of Aden,” China Military Online, November 23, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8031368.html; Guan Lei and Xiao Delun, “13th and 14th Naval Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission-Handover,” China Military Online, March 15, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8168363.html; “China’s 13th Escort Fleet Returns from Somali Waters,” Xinhua, May 23, 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-05/23/c_132404107.htmhttp://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8168363.html. TF 14: “Chinese Flotilla Sets Sail on Escort Missions,” Xinhua, February 16, 2013, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/HomePicture/2013-02/16/content_4432892_4.htm;

[11th Escort Taskforce Returns to the Embrace of the Mother Country], Qingdao Finance Daily, 6 September 2012, http://qd.wenming.cn/syjj/201209/t20120906_345091.html. TF 12: Cheng Bijie and Hou Rui, “12th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns Home After Visiting Vietnam,” China Military Online, January 15, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8092041.html; Cheng Bijie and Hou Rui, “12th and 13th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission Handover,” China Military Online, November 23, 2012, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2012-ll/23/content_5109609.htm; 12th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns Home,” China Military Online, January 22, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8101766.html. TF 13: Zhu Shaobin and Xiao Jiancheng, “13th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Arrives in Gulf of Aden,” China Military Online, November 23, 2012, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8031368.html; Guan Lei and Xiao Delun, “13th and 14th Naval Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission-Handover,” China Military Online, March 15, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8168363.html; “China’s 13th Escort Fleet Returns from Somali Waters,” Xinhua, May 23, 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2013-05/23/c_132404107.htmhttp://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8168363.html. TF 14: “Chinese Flotilla Sets Sail on Escort Missions,” Xinhua, February 16, 2013, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/HomePicture/2013-02/16/content_4432892_4.htm;

![]() [Zhu Ennan], “

[Zhu Ennan], “

![]() ” [14th Escort Taskforce Returns to Mother Country after Completing Various Missions],

” [14th Escort Taskforce Returns to Mother Country after Completing Various Missions],

![]() [China National Radio Network], September 29, 2013. TF 15:

[China National Radio Network], September 29, 2013. TF 15:

![]() [Pan Jieting],

[Pan Jieting],

![]() [Xiao Yong], and

[Xiao Yong], and

![]() [Yang Pengyu], “

[Yang Pengyu], “

![]() ” [15th Escort Taskforce returns Triumphantly: Naval Political Commissar Vice Admiral Wang Sentai Attends Welcoming Ceremony],

” [15th Escort Taskforce returns Triumphantly: Naval Political Commissar Vice Admiral Wang Sentai Attends Welcoming Ceremony],

![]() [Zhanjiang Daily], January 24, 2014, http://paper.gdzjdaily.com.cn/html/2014-01/24/content_3_5.htm. TF 16: “

[Zhanjiang Daily], January 24, 2014, http://paper.gdzjdaily.com.cn/html/2014-01/24/content_3_5.htm. TF 16: “

![]()

![]() ” [16th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns to Qingdao After Completing Missions],

” [16th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Returns to Qingdao After Completing Missions],

![]() [China News Net], July 18, 2014. TF 17:

[China News Net], July 18, 2014. TF 17:

![]() [Hou Rui] and

[Hou Rui] and

![]() [Liu Ya], “

[Liu Ya], “

![]() ” [17th Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Zhoushan to Implement Search and Rescue for Lost Malaysian Airliner and Escort Duties in the Gulf of Aden and Somali Waters],

” [17th Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Zhoushan to Implement Search and Rescue for Lost Malaysian Airliner and Escort Duties in the Gulf of Aden and Somali Waters],

![]() [China Military Online], March 25, 2014, http://www.chinamil.com.cn/jfjbmap/content/2014-03/25/content_71160.htm;

[China Military Online], March 25, 2014, http://www.chinamil.com.cn/jfjbmap/content/2014-03/25/content_71160.htm;

![]() [Dai Zongfeng] and

[Dai Zongfeng] and

![]() [Liu Yaxun], “

[Liu Yaxun], “

![]() ” [17th Chinese People’s Liberation Army Naval Escort Taskforce Triumphantly Returns to China],

” [17th Chinese People’s Liberation Army Naval Escort Taskforce Triumphantly Returns to China],

![]() [China News Service], October 22, 2014, http://www.chinanews.com/mil/2014/10-22/6707067.shtml. TF 18:

[China News Service], October 22, 2014, http://www.chinanews.com/mil/2014/10-22/6707067.shtml. TF 18:

![]() [Xiao Yong] and

[Xiao Yong] and

![]() [Ceng Xingjian] “

[Ceng Xingjian] “

![]() ” [17th Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Zhoushan for the Gulf of Aden],

” [17th Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Zhoushan for the Gulf of Aden],

![]() [China News Service], August 1, 2014, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2014-08-01/1348793357.html. TF 19: “19th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Qingdao,” China Military Online, December 3, 2014, http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2014-12/03/content_6253028.htm; TF 20: “

[China News Service], August 1, 2014, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2014-08-01/1348793357.html. TF 19: “19th Chinese Naval Escort Taskforce Sets Sail from Qingdao,” China Military Online, December 3, 2014, http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2014-12/03/content_6253028.htm; TF 20: “

![]() ” [Chinese Navy 19th, 20th Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission Handover], Xinhua, April 23, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/world/2015-04/23/c_1115067147.htm

” [Chinese Navy 19th, 20th Escort Taskforces Conduct Mission Handover], Xinhua, April 23, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/world/2015-04/23/c_1115067147.htm

China’s operations in the Gulf of Aden have given the PLAN experience with many aspects of this transition. Accolades garnered while serving in the Gulf of Aden are, in some cases, relevant to broader Chinese naval development in the sense that the skills and experiences of anti-piracy personnel are valued upon their return home.

•

Creativity and Inter-Agency Cooperation

While frequently touted in China and abroad as an example of cooperation with other navies, China’s initial and proceeding anti-piracy deployments have also catalyzed interagency coordination unprecedented in scale, extent and impact. For example, PLA No. 425 Hospital regularly supports officers and sailors deployed to the Gulf of Aden with real-time medical “teleconsultations” with Sanyabased staff.113 Similarly, operations in the Gulf of Aden have spurred civil-military coordination among the navy and agencies such as the MOT that transcends bureaucratic barriers. Increasingly advanced and integrated network technology, including China’s growing Beidou positioning, navigation and timing satellite system,114 supports these efforts. The PLAN Control Center and MOT’s China Maritime Search and Rescue Center (CMSRC) jointly track the locations and status of relevant Chinese merchant ships, aboard which the MOT has installed devices that support a “maritime satellite-based ship movement tracking system.” Supported by newly developed software, the system facilitates features including “all-dimensional tracking” and video-based communications “at all times.”115 Additionally, in January 2014 the 16th escort task force employed an airborne video transmission system to snap photos of four suspicious vessels, which were sent to commanders in real time, allowing for Chinese warships to repel the vessels.116

This coordination is bolstered significantly by new ways of communicating that allow China to deploy new technologies with a wide range of applicability. Reportedly required by PLAN Commander Wu Shengli from the outset, anti-piracy task forces benefit from cutting-edge telecommunications. Yang Junfei, 11th task force Commander, stated that his flotilla has multiplied its overall efficiency through a transformation of its “original short-wave communication” system to one “composed of multiple satellite communication transmission networks.” The latter facilitates reporting escort situations, exchanging information with other navies, communicating with commercial ships in need of escort and organizing escort convoys.117

The operational challenges of Somalia have also catalyzed PLAN creativity. The complex nontraditional security threat of contemporary maritime piracy has forced PLAN forces to accustom themselves to reacting in unrehearsed ways, a significant departure from pre-Gulf of Aden times, when many PLAN sailors relied on rote procedures. Events force PLAN personnel to depart from the script of contingency plans they previously memorized. As mentioned above, in July 2012, Changzhou was responsible for picking up and transferring 26 civilian crewmembers of pirated Taiwan fishing vessel Shiuh-fu 1. The freed hostages were left on a Somali beach, which required the PLAN to perform an unprecedented shore landing and pick-up. Wave conditions prevented Changzhou from approaching shore. To search the surf zone, it sent two dinghies with five Special Forces members and four sailors. The team located the released hostages but was unable to extract them in the boats because of high waves near shore.

Changzhou dispatched a helicopter, but the wet, sandy beach frustrated landing. Darkness threatened the freed hostages with the possibility of recapture. Two seasoned Special Forces members were therefore deployed to the beach to facilitate the helicopter’s landing, after which PLAN forces were finally able to pick up the twenty-six hostages.118 Recounting the event, helicopter pilot Chen Wengang recalled, “I could see they were terrified from their eyes when we finally met at the beach on the Somali coast.”119

Streamlined coordination and consistent improvisation have collectively stimulated PLAN efficiency over six-plus years of continuous escorts has increased the PLAN’s Far Seas operations efficacy. For instance, the PLAN has increased the scope and versatility of convoy formations escorting warships and commercial vessels, employing multiple and combined escort procedures to best coordinate schedules and ship characteristics. China performs escorts 5 miles [9 km] north of the Internationally-Recommended Transit Corridor (IRTC), in parallel to other navies. 450 miles [833 km] long, the IRTC is divided into 25×25 mile [46X46 km] blocks. One-column convoys arrange the merchant ships in an equidistant pattern, typically flanked by one warship, which travels at a speed similar to that of the flotilla.

Recent anti-piracy escort task forces have lasted about six or seven months between departing and returning to home port, though both the 16th and 17th task forces worked for an extended duration to help with other nontraditional security missions such as Syrian chemical weapons destruction and commercial aircraft search operations. Task forces rotate duties in the Gulf of Aden every three or four months. Mirroring increases in time at sea for PLAN ships is the aggregate number of commercial escorts they have performed.120 For instance, China used over 300 days to escort 1,000 ships, over 220 more days to reach 2,000 escorts, and just over 180 additional days to reach its milestone of 3,000 escorts.121 These are significant milestones, given the precision that escort operations demand, with ships of different speeds and schedules coming through the Suez Canal’s time-limited gates.

With time China has streamlined its naval escort operations. PLAN warships adopt different escort formations in response to unpredictable circumstances such as the number and type of commercial ships, weather, region and PLAN capacity. Formations include single-, double- and hybrid-style columns, and sometime involve grouping commercial escortees by their relative displacements, speeds and features.122 Additionally, as seen during 9th task force operations, a commercial vessel with a lower freeboard—potentially more vulnerable to boarding by pirates—might be placed closer to PLAN warships.123 In previous cases PLAN task forces have assigned one surface platform, usually a guided missile frigate, to linger for extended periods at escort rendezvous points whenever certain merchant vessels are tardy due to weather, ship-specific constraints and so on.124

Just as escort tactics provide demonstrable examples of PLAN anti-piracy adaptation and creativity, the evolving operations of Special Forces deployed for PLAN escorts represent a critical feature of China’s anti-piracy apparatus. Learning from early operations, recent Special Forces detachments have boarded certain commercial ships, such as those on the outside of the convoy and/or with lower freeboards, to provide on-ship anti-piracy protection.125 They have repeatedly conducted integrated training with civilian seafarers to combat piracy jointly.126

In addition to operational innovations, the PLAN has utilized six-plus years of anti-piracy deployments away from home to achieve flatter command structures, facilitating more efficient intra-naval coordination. Operations with the scale and scope of China’s Gulf of Aden deployment demand tight synchronization among manifold Chinese civil and military actors. To be sure, the command structure of the task forces mirrors that of PLAN headquarters, where many task force commanders are normally billeted, with a commanding officer (

![]() ), political commissar (

), political commissar (

![]() ), deputy commanding officer (

), deputy commanding officer (

![]() ) and heads of four groups: command group (

) and heads of four groups: command group (

![]() ), political works group (

), political works group (

![]() ), logistics group (

), logistics group (

![]() ) and equipment group (

) and equipment group (

![]() ).127 But within this overall framework, China’s Navy has adopted an unusually flattened command structure through which CMC orders can be passed directly to anti-piracy vessels without having to first transit fleet and base command levels. This allows anti-piracy task forces to receive authoritative commands and respond more quickly.

).127 But within this overall framework, China’s Navy has adopted an unusually flattened command structure through which CMC orders can be passed directly to anti-piracy vessels without having to first transit fleet and base command levels. This allows anti-piracy task forces to receive authoritative commands and respond more quickly.

Similarly, the Comprehensive Planning Department of the PLAN’s Equipment Department established a “shipping escort action equipment support administrative organization,” and reportedly assigned a staff member specific responsibilities concerning shipping escort equipment organization and support. This institution has been tested continuously by unexpected incidents. For example, while en route to Libya’s coast to assist China’s evacuation of overseas nationals in 2011, frigate Xuzhou experienced a malfunction. The Equipment Department urgently worked with “diplomatic, civil aviation, Customs, Maritime Affairs and Public Security organizations, even delaying the takeoff of a scheduled flight.” Technology and flatter coordination structures have likewise deepened civil-military integration:

...it sent the spare parts on an outbound flight and thereby assured that the follow-on task could be executed. From getting the spare parts ready to clearing the malfunction all that distance away took only two days. Moreover, for emergency resupply of special weapons ammunition for the first shipping escort formation, an ordnance support organization finished arranging for more than 40,000 special weapons items to be delivered to the port of departure from various locations in China in 28 hours.128

One of the PLAN Deputy Commanders, Vice Admiral Ding Yiping, declared in December 2013 that the PLAN had no plans then to deploy an aircraft carrier formation to the Gulf of Aden to fight piracy. Interestingly, however, he suggested that the PLAN would expand patrols on the East African coastline, and intensify escorts for UN World Food Program (WFP) vessels. Given that the PLAN’s primary contributions to Gulf of Aden security have been ship escorts rather than zoned patrols, it remains unclear if Chinese naval ships will start patrolling East Africa’s coast regularly as Ding suggests.129 Regardless, China’s Yuzhao-class Type 071 LPDs, as well as Liaoning, remain the PLAN’s strongest surface platforms available for supporting anti-piracy and other nontraditional security operations. Type 071 flagship Kunlunshan participated in the 6th escort task force. Jinggangshan, a $300 million, 200-meter Type 071 amphibious landing ship is equipped with four hovercraft and two Z-8 helicopters, and crewed by 800 officers and sailors. It deployed with the 15th task force in 2013.130

•

Equipment

Sustaining a large-scale security mission for over six years beyond the Asia-Pacific offers Chinese naval planners a testing ground for new platforms and development ideas. The military importance attached to the Gulf of Aden mission stems largely from the operational experience gained by China’s Navy, which the PLAN is able to apply to many of its other operations, including traditional, combat-based objectives in the Near Seas. For example, many of China’s most advanced guided missile frigates, including Huangshan, Yuncheng and Weishanhu of the SSF, have deployed off Somalia, and sport some of the PLAN’s strongest anti-aircraft, anti-missile and anti-submarine systems.131 These PLAN surface platforms transit various strategic waterways en route to the Gulf of Aden, including the Chinese-claimed Paracel (Xisha) and Spratly (Nansha) islands in the South China Sea, as well as the Strait of Malacca and the Indian Ocean.132

The Type 056 Jiangdao-class frigate was introduced into the PLAN for the first time in 2013. While it appears to fill a much-needed role in China’s Near Seas defense by providing a balance between power and speed, it also seems potentially useful in nontraditional security operations such as anti-terrorism, anti-piracy, border control and anti-drug activities.133 30mm remote control ship guns on both sides of the Type-056’s bridge are ideal for low-intensity conflicts, and appeared first in the Gulf of Aden on replenishment vessel Qinghaihu,134 Similarly, Chinese surface vessels such as search and rescue vessel Haixun 01 are increasingly equipped with sound amplifier and water cannon equipment that allow PLAN sailors to deter pirates and other low-intensity threats using non-fatal means.135 Of course, the Type 056 frigate appears to be primarily designed for Near Seas application. ONI summarizes its capabilities as follows: “The Jiangdao is ideally-suited for general medium-endurance patrols, counterpiracy operations and other littoral duties in regional waters, but is not sufficiently armed or equipped for major combat operations in blue-water areas.”136

Meanwhile, the PLAN has deployed its most advanced amphibious ships to the Gulf of Aden, such as the Jinggangshan amphibious transport dock (one of four Type 071 vessels; additional hulls likely soon),137 which possess advanced air defense and anti-submarine abilities. The experience these ships and their crews accumulate off Somalia represent important steps for building combat readiness absent traditional maritime conflicts or other opportunities to gain live experience.138 Some Chinese experts view this as the PLA’s most valuable current operational involvement, given that the PLAN has not had actual combat experience since the 1988 Johnson South Reef Skirmish. While U.S. and other foreign naval experts may be quick to dismiss the comparison for want of direct parallels, it is important to consider the PLA’s long tradition of learning where it can and making do with what it has. Increasingly sophisticated PLAN exercises underway include targeted opposition force drills with in-depth hot washes to learn from successes and failures.

Meanwhile, Type 071 vessels, currently the PLAN’s largest comprehensive amphibious warships with a displacement of over 20 tons, offer a wider deck and greater ability to introduce helicopters into war fighting training and operations in the Gulf of Aden.139 The ongoing development of the “Type 081” landing helicopter dock promises another advanced platform suitable for Gulf of Aden and other anti-piracy missions. In 2007, data merged suggesting that China is developing a Type 081 landing ship that will be able to transport twelve helicopters and a crew of over 1,000 for a month at a time.140 ONI describes this as “a follow-on [to the 071] amphibious assault ship (LHA) that is not only larger, but incorporates a full-deck flight deck for helicopters.”141

Need to constantly supply Gulf of Aden task forces appears to have helped drive an increase in China’s fleet of replenishment oilers (AORs). For years the PLAN had five Fuchi-class AORs, its largest, most advanced; two more were added in 2013 and 2014 respectively, bringing the total to 9 today.142

Rotary wing aircraft (helicopters) have played an important role in maritime domain awareness and SOF deployment. Every helicopter-capable PLAN combatant can deploy one of the PLAN’s roughly 20 Z-9Cs. This workhorse airframe may be fitted with a KLC-1 search radar, dipping sonar and a lightweight torpedo. The upgraded Z-9D naval variant “has been observed carrying ASCMs.” In a sign of possible customization to support Gulf of Aden operations, several Z-9Cs conducting anti-piracy escorts have been observed with “a new roof-mounted electro-optical (EO) turret, unguided rockets, and 12.7mm machine gun pods.” The Z-8 medium-lift helicopter offers greater cargo capacity, but its larger size precludes deployment on some PLAN combatants. During Gulf of Aden anti-piracy deployments, “several Z-8s were seen with weapons pylons that are capable of carrying up to four armament pods—the same rocket and 12.7 mm machine gun pods seen on the Z-9Cs.”143

In addition to traditional surface and aviation platforms, the PLAN boasts a burgeoning fleet of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs), as well as an increasingly sophisticated collection of unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs).144 Particularly in the case of China’s more advanced UAVs, these autonomous platforms could be applied increasingly to Gulf of Aden and other Far Seas maritime operations. The PLAN has already deployed multiple types of UAVs, such as the BZK-005 and the S-100, in the Near Seas.145

The most dramatic example to date of new, operationally relevant experience derived from ongoing anti-piracy task forces, however, is China’s unprecedented submarine deployments into the Indian Ocean, Gulf of Aden, Persian Gulf, and possibly soon to other bodies of water. While these deployments have been ostensibly to support anti-piracy escorts, DoD judges that “the submarines were probably also conducting area familiarization, and demonstrating an emerging capability both to protect China’s sea lines of communications and increase China’s power projection into the Indian Ocean.”146

On December 3, 2013, the Ministry of National Defense Foreign Affairs Office (MNDFAO) informed Indian military attachés that a Chinese submarine would enter the Indian Ocean, for the first time ever. Officials from the United States, Singapore, Indonesia, Pakistan and Russia were likewise notified. From December 13, 2013 to February 12, 2014, a Shang-class (Type 093) nuclear-powered attack submarine (SSN) navigated near Sri Lanka and into the Persian Gulf, transiting the Strait of Malacca on the way to and from its home port on Hainan Island.147

In September 2014, MNDFAO once again summoned foreign attachés to announce that another dispatch was imminent—this time China’s first deployment of a conventionally powered submarine to the Indian Ocean. Attachés were informed that “the subs entering the Indian Ocean would assist anti-piracy patrols off Somalia.”148 Song-class (Type 039) Great Wall No. 329 from the South Sea Fleet made Beijing’s first formal submarine visit to a foreign country when it visited Colombo, Sri Lanka from September 7-14. Accompanied by North Sea Fleet comprehensive supply ship Changxing Lake (pennant number 861), it docked at Colombo International Container Terminal, built with a Chinese investment of $500 million.149 Queried by fax by Bloomberg News, MNDFAO stated, “The submarine stopped in Colombo en route to the Gulf of Aden off the coast of Somalia to join a navy escort mission.”150 Song 329 and Changxing Lake docked in Colombo again on October 13, where they remained five days for “refueling [sic] and crew refreshment.”151

In an interesting example of art emulating life, a PLAN-produced TV series on the Gulf of Aden mission hints at similar submarine activities.152 After serving as Political Commissar in the first Gulf of Aden task force beginning in Episode 1, in Episode 34 protagonist Xiao Weiguo departs Yulin Naval Base on a forty-day deployment in what is clearly a Song-class submarine.153

Shortly before this study went to press, too late to be included in DoD’s 2015 report, a Han-class (Type 091) likewise entered the Indian Ocean and called on a port in the Gulf of Aden for the first time, operating in conjunction with an anti-piracy task force (possibly the 19th) for “more than two months,” until April 22, 2015.154 In a CCTV interview, Yu Zhengqiang, the Qingdao-based submarine’s deputy commander, enumerated challenges that he and his crew had to overcome: “This escort mission had multiple major safety concerns. First, there were concerns about all the equipment and facilities, and second [we had to] deal with various challenges while navigating totally unknown waters, which was complicated by military intelligence issues.”155 According to one article, “CCTV broadcast footage of the improved type 091 nuclear submarine for the first time, indicating that the submarine’s escort missions in the region will become a standard exercise.”156 If so, from a naval development perspective, some of the most exciting elements of Chinese Gulf of Aden deployments will increasingly occur underseas.

•

Personnel

Extended voyages where personnel are often at sea for months at a time require PLAN crews to master both logistical duties and personal health challenges. PLAN crews sent to the Gulf of Aden rise at 6:20 a.m. and discharge their duties for eight to ten hours daily. The PLAN assigns psychiatrists to address mental challenges faced by crewmembers, who are encouraged to take advantage of limited deck space, and are permitted to use the Internet on weekends.157 Fu Guanghai, a PLAN sailor stationed on supply ship Weishanhu, stated that “We call home about twice a month, but the length must be kept below five minutes each time, which is not a lot when you count the dialing time in.”158

Like surface platforms, naval personnel continue to accumulate otherwise unavailable Far Seas operational proficiency. First, naval operational modernization has the backing of China’s top leadership to a historically unprecedented degree. Moreover, Chinese leaders are ideally positioned to guide PLAN modernization in the coming years. Xi Jinping’s retention of Admiral Wu Shengli as PLAN commander, for instance, represents a strong vote of confidence of Wu’s leadership since 2007, which has spanned the inaugural and subsequent 15 PLAN Gulf of Aden deployments. Xi had a chance to replace him, but did not, despite replacing all other senior PLA flag officers in similar positions. It seems likely that Xi sees a kindred spirit in Wu: a confident, extroverted, vigorous leader from a Party family with the father formerly a leader in the son’s professional circle. Wu is also experienced in executive positions, with a temperament and physical, hands-on approach well suited to riding herd over an ambitious modernization process.159

Second, below the highest echelon of naval leadership, the PLAN is cultivating an elite cadre of officers, many of whom possess Gulf of Aden experience. Top leadership talents have been rotated through Gulf of Aden deployments before assuming prominent leadership positions. In particular, extensive service by key individuals highlights the connection between Gulf of Aden anti-piracy experience and naval promotion. For instance, Rear Admiral Qiu Yanpeng, once deputy commander of the East Sea Fleet (ESF), was promoted to NSF commander in early 2014. The promotion came after Qiu served as commander of the 4th escort task force while ESF deputy chief of staff over three years earlier. Qiu is now dual-hatted as PLAN Chief of Staff and Director of the PLAN Headquarters Department.

Around the same time that Qiu was promoted to NSF commander, his predecessor Vice Admiral Tian Zhong, who also has served in the Gulf of Aden, became a deputy commander of the PLAN. Now the most senior of five PLAN deputy commanders, he may eventually become a member of the powerful Navy Party Standing Committee (NPSC),160 or “Navy Politburo.”161 In 2011, Tian gave a presentation in London on international panel of naval officers. The following year, he was chosen for the 18th CCP Central Committee.

North Sea Fleet (NSF) Commander RADM Yuan Yubai, although a career nuclear submariner, led the 14th task force in 2013 before being promoted to his current position in July 2014. The ascent of Qiu, Tian and Yuan signals that Beijing places high importance on blue water experience within the highest echelons of naval leadership.162

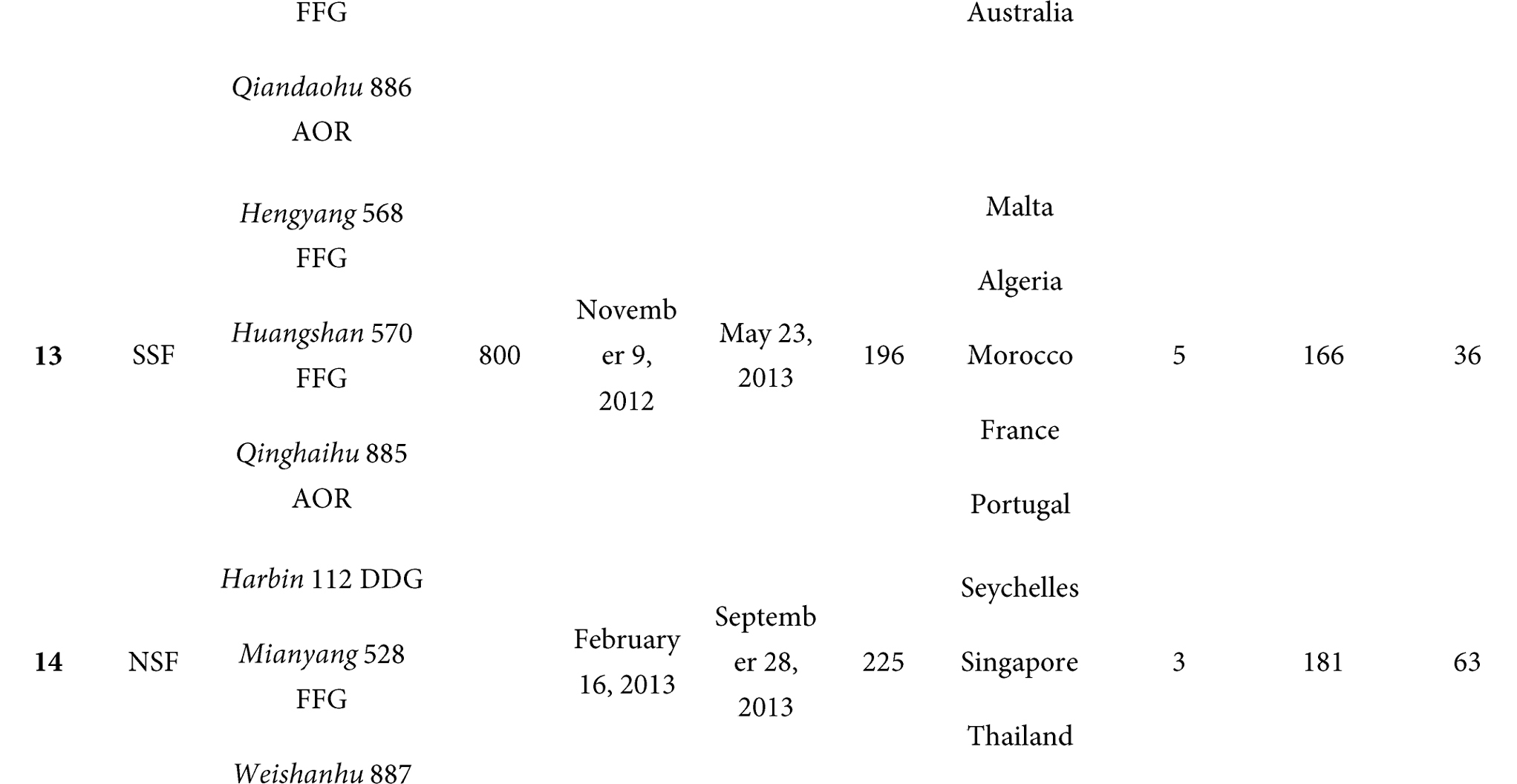

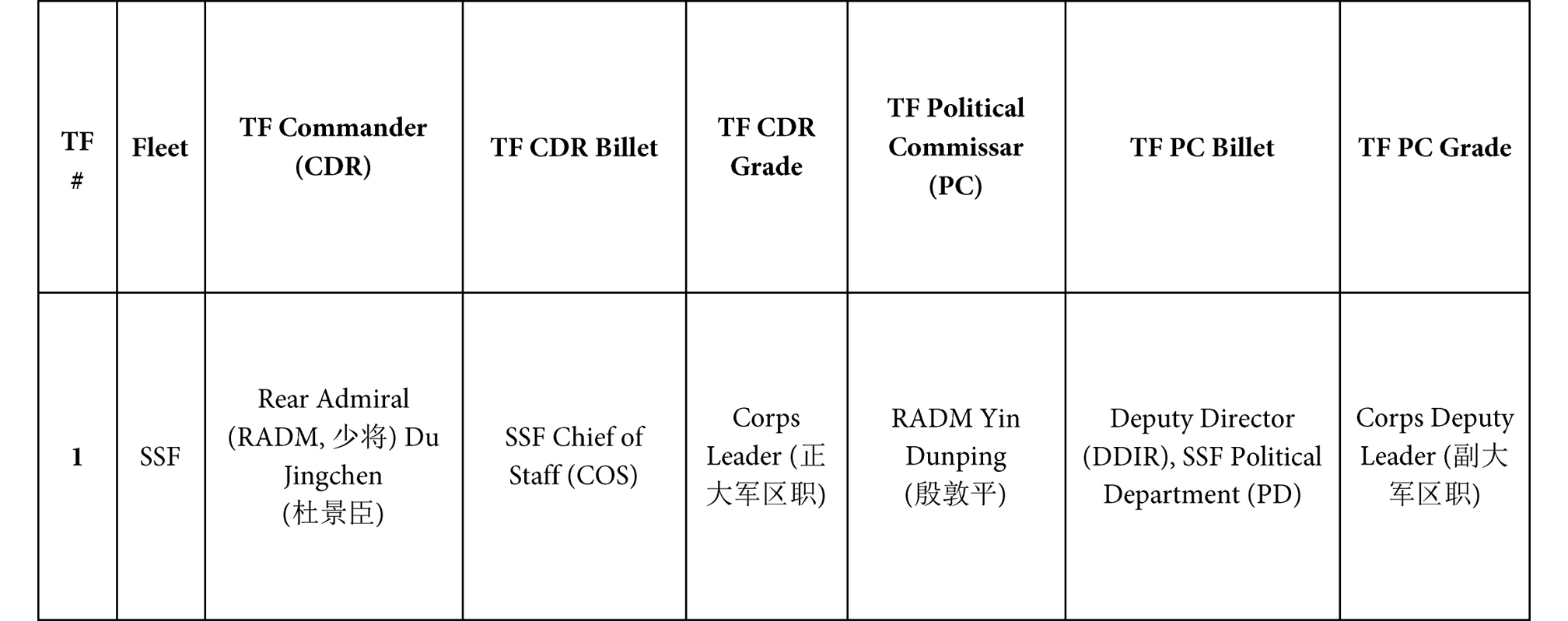

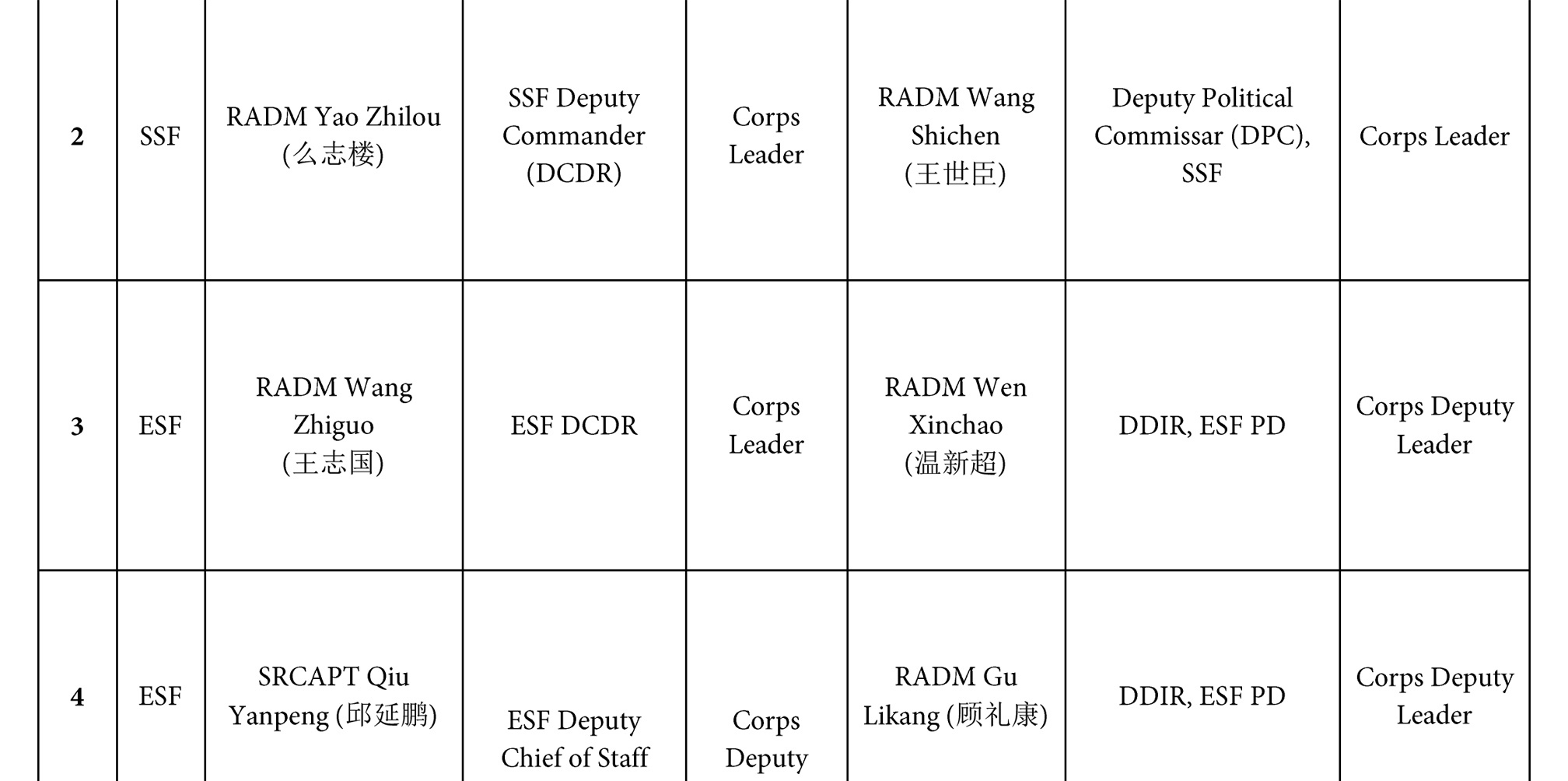

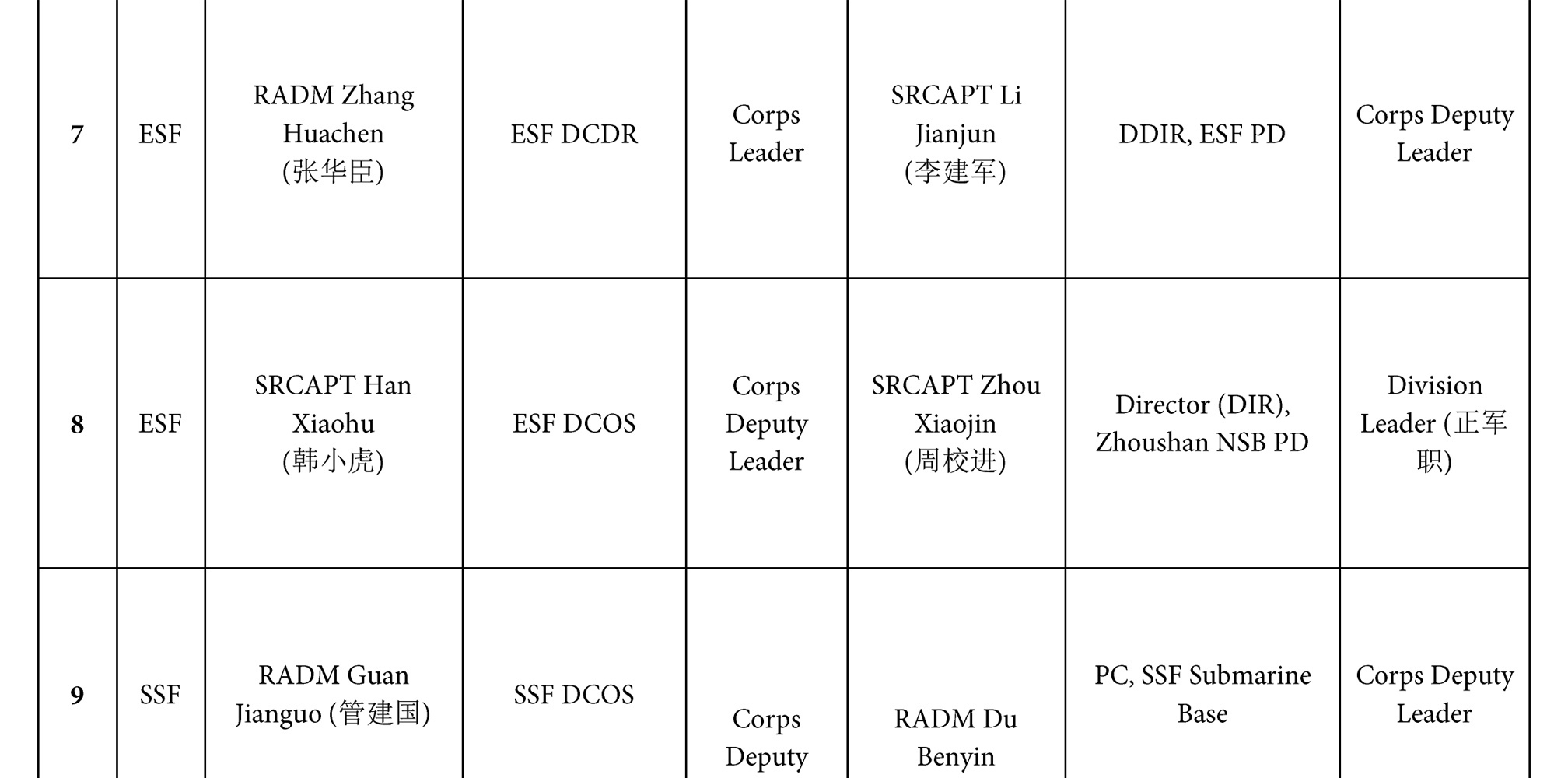

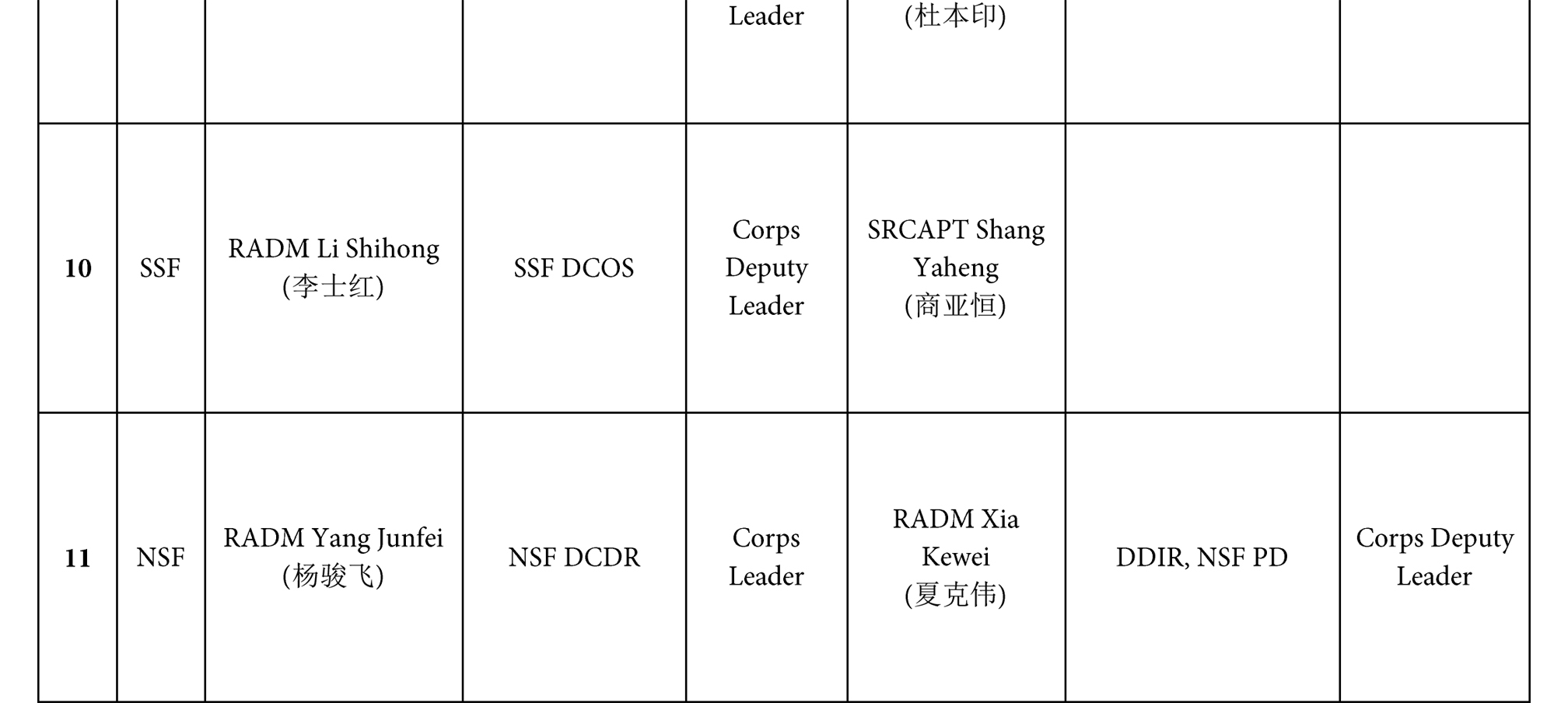

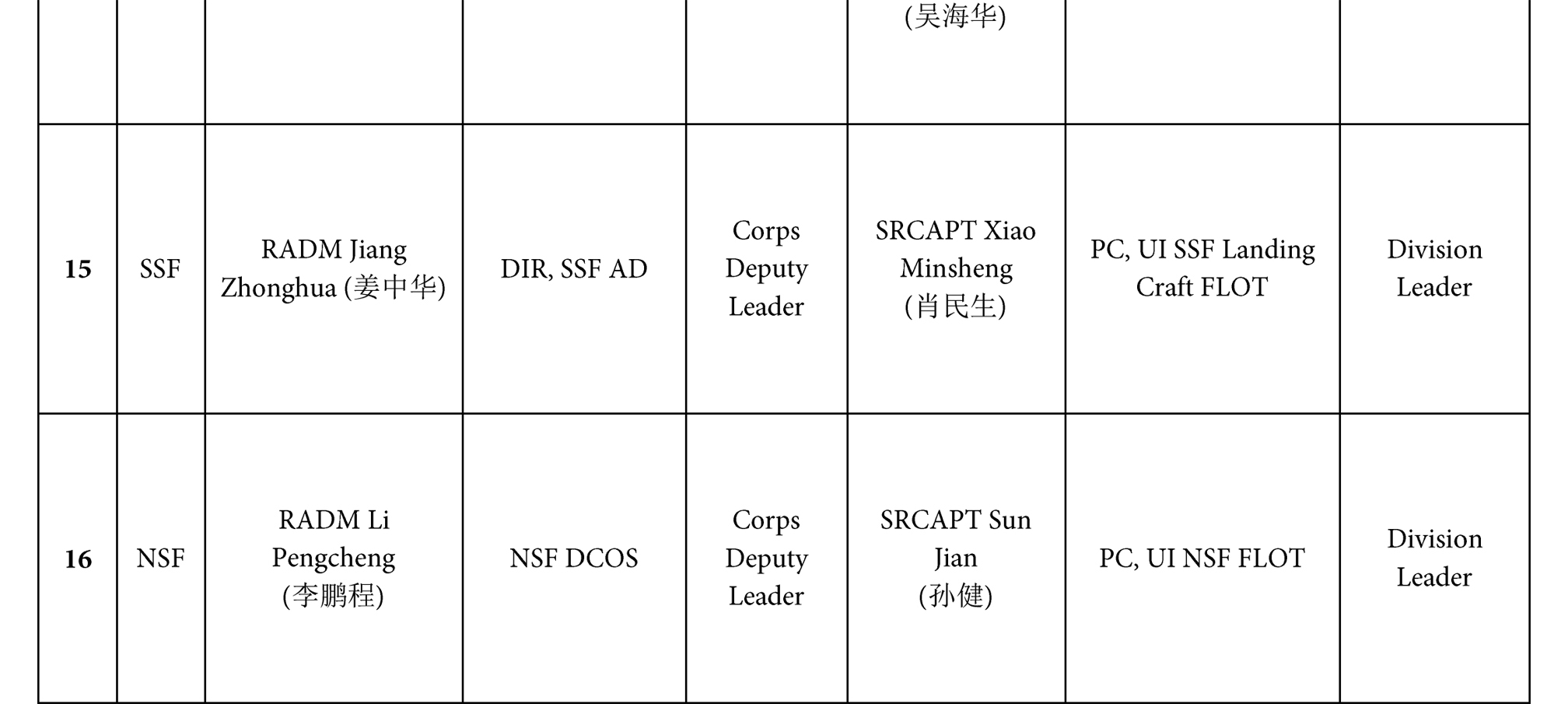

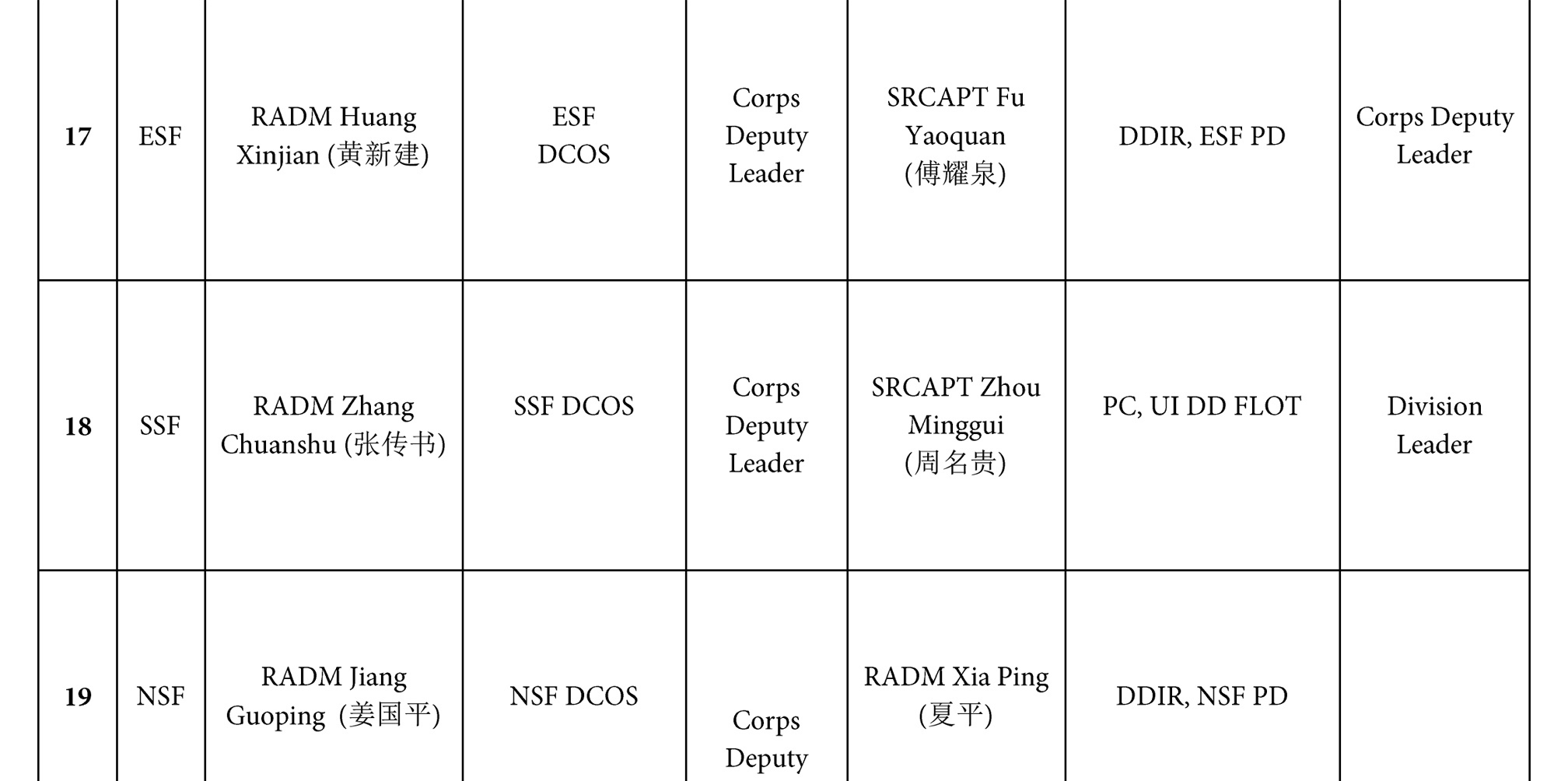

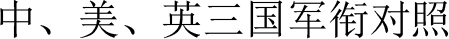

This suggests that the PLAN often views Gulf of Aden experience as a significant checkbox for its leadership to tick off, proving their competence in real Far Seas operations before earning promotion. That Far Seas experience is apparently an important consideration for naval career advancement reflects the service’s gradual reorientation to the Far Seas. Exhibit 2 lists all individuals who have captained PLAN Gulf of Aden task forces, as well as their subsequent career paths.

EXHIBIT 2: PLAN Anti-Piracy Escort Task Force Leaders with Rank, Billet and Grade

Note: All ranks and grades at time of TF command. Ranks converted to closest English equivalents per “

![]() ” [Ranks in the Chinese, U.S. and UK Armed Forces], http://language.chinadaily.com.cn/focus/rank/rank.html. The following are approximate equivalents: the four-star position —

” [Ranks in the Chinese, U.S. and UK Armed Forces], http://language.chinadaily.com.cn/focus/rank/rank.html. The following are approximate equivalents: the four-star position —

![]() (Admiral, First Class) is above four-star U.S. Navy (USN) Admiral but below five-star U.S. Fleet Admiral. The three-star position

(Admiral, First Class) is above four-star U.S. Navy (USN) Admiral but below five-star U.S. Fleet Admiral. The three-star position

![]() (Admiral) is roughly similar to a four-star USN Admiral. The two-star position

(Admiral) is roughly similar to a four-star USN Admiral. The two-star position

![]() (Vice Admiral) is similar to three-star Vice Admiral in the USN. The one-star

(Vice Admiral) is similar to three-star Vice Admiral in the USN. The one-star

![]() (Rear Admiral) is similar to a two-star USN Rear Admiral (upper half/RADM), but above a one-star USN Rear Admiral (lower half/RDML).

(Rear Admiral) is similar to a two-star USN Rear Admiral (upper half/RADM), but above a one-star USN Rear Admiral (lower half/RDML).

![]() (Senior Captain) is decidedly below the largely-discontinued USN rank of Commodore (rendered in Chinese as

(Senior Captain) is decidedly below the largely-discontinued USN rank of Commodore (rendered in Chinese as

![]() ), but slightly above the position of USN Captain, akin to a captain, upper half. To facilitate comparison U.S./Western naval nomenclature, “

), but slightly above the position of USN Captain, akin to a captain, upper half. To facilitate comparison U.S./Western naval nomenclature, “

![]() ” is translated as “flotilla.”

” is translated as “flotilla.”

Exhibit 2 Sources:

Chinese military and state media sources, including People’s Navy, Liberation Army Daily, Xinhua, China Daily and People’s Daily.

Prior to the first anti-piracy deployment, Ma Luping, Director of the Operations Department of the GSD Naval Operations Bureau, participated in an MND press briefing on the deployments.163 Moreover, while no serving NSF, SSF or ESF commanders have participated, the experience of Du Jingchen and other Gulf of Aden task force commanders suggests that experience off of Somalia pays dividends for career development. Du commanded the inaugural escort task force, and later was promoted to Vice Admiral, ESF Commander and Navy Chief of Staff (COS).164 More broadly, five serving or future fleet Deputy Commanders have commanded Gulf of Aden anti-piracy task forces.165 One Fleet COS, another former one and four deputy COS, have commanded anti-piracy task forces.166 There is a strong correlation between anti-piracy task force command and high current or future rank.

Third, the PLAN sailors and auxiliary crewmembers sent to the Gulf of Aden are gaining a competitive advantage over Chinese sailors who stay home. For example, Ma’anshan Executive Officer Dong Qian reported that he had personally participated in two Gulf of Aden deployments.167 PLAN sailors have conducted training involving “sea-and-air target searching, warship operation, navigation and mapping, early warning and detection,” outside of China’s territorial boundaries while sailing towards the Gulf of Aden.168 SSF Naval Aviation Headquarters Director Liu Dehua remarked that there exists an urgent need to cultivate naval pilots to meet new task requirements accompanying the PLAN’s expansion into the Far Seas.169 Similarly, University of New South Wales scholar You Ji finds that “The hours and sorties of helicopter pilots in a four-month rotation in the Gulf of Aden far exceed their whole year’s flight time at home.”170 This includes a wide range of all-weather nighttime training involving “blackout procedures,” in which pilots can barely see the sea surface, to strengthen ability to counter nocturnal pirate attacks.171

The PLAN has emphasized training before, during and after escort operations. In January 2013, for instance, the PLAN Command College in Nanjing conducted a two-week training module for 70 cadets from “leading organs and troop units.” The module “adopted many training forms including case analysis, problem exercise, simulated training and comprehensive drill to teach naval escort basic theory and exchange practical experience of naval escort.” It also involved drills teaching cadets how to react to unexpected incidents, such as pirate attacks on commercial ships.172 This training followed a similar module initiated in February 2012 lasting for two weeks, during which eighty-four PLAN leaders attended training for high-level officers.173 PLAN anti-piracy task forces also participate in extensive pre-departure training which includes officer instruction, and, for lower-level sailors, “72 action programs in four categories, 150 emergency plans in response to various scenarios and 15 drill scenarios of various types.”174

Equally interesting is the parallel emphasis placed by China’s Navy on anti-piracy training while en route to, and once having arrived in, the Gulf of Aden. Most recently, training for Special Forces in the 16th escort task force included warning fire as well as shooting practice involving sniping, light weapons and special ammunitions drills in the western Gulf of Aden, where waves, currents and winds rocked PLAN warships and increased the difficulty of shooting accurately.175 PLAN training also involved working with commercial personnel, including the management of rendezvous, cooperation with merchant captains, deciding on optimal escort formations and making adjustments based on limitations of certain vessels.176

The composition of recent task forces underscores the intense, often iterated training that PLAN personnel deployed off Somalia receive. During the 7th task force, for example, over half of all officer and sailors were deploying to the Gulf of Aden for at least a second time, which suggests both that one mission may be insufficient to instill critical skills and that China’s Navy is building an elite front line of naval personnel.177 The latter point is reflected by Rear Admiral Xiao Xinnian’s initial remarks at the MND’s press conference in December 2008 announcing the escort mission. Xiao remarked, “Our officers and men must, before anything else, accomplish the mission they have undertaken. There is no problem with that part. All the officers and men aboard these three vessels are well trained and have received necessary preoperational training in light of this mission. ...this kind of mission poses no problem for our officers and men.”178

•

Military Diplomacy

Besides simply raising operational competence across various personnel strata, China’s leadership appears intent on utilizing China’s Far Seas posting in the Gulf of Aden for a diverse portfolio of objectives, including diplomacy. Maintaining an active anti-piracy naval presence that consists of two to three large warships roughly 10,000 km from Chinese territorial waters opens considerable aperture for naval diplomacy and soft power projection. Since early 2009, PLAN warships have docked in over thirty littoral states in East Asia, the Indian Ocean Region (IOR), Africa, the Middle East and Europe for rest and replenishment, friendly visits, joint training and other objectives. In its first protracted naval operation in the international spotlight on—and especially visible before other navies and international observers—the PLAN has gained confidence and recognition regarding the quality of its naval operations. Heightening China’s international status, the mission has undoubtedly spurred further debate in China about Beijing’s provision of public goods. A full range of PLAN leaders regularly laud the navy’s contributions in this regard during public appearances, including Rear Admiral Xiao Xinnian, one of the PLAN Deputy Chiefs of Naval Staff, who asserts that the mission “showcased China’s positive attitude in fulfilling its international obligations and the country’s image as a responsible stakeholder.”179

The PLAN is engaging the outside world more intensely than ever before. While it has actively pursued a wide range of naval activities, from disaster relief, to maritime medical services, to joint combat and non-combat exercises with other navies, none of these operations are comparable to the Gulf of Aden mission in scale and duration. Increasingly, it appears that Gulf of Aden experience, as well as other Far Seas exposure through training, joint exercises and humanitarian missions, are used as yardsticks for professionalism among PLAN leaders that have real impacts on their career progression. In 2011, Liberation Army Daily reported that the PLAN would install larger, brighter PLAN ensign flags on their surface platforms, viewed by Chinese maritime expert Ni Lexiong as an indication of China’s “determination to be a sea power, because all its new standards have been learned from Western maritime powers like the United States.”180

China Military Online, a media website supported by military mouthpiece Liberation Army Daily, ranked ten highlights of Chinese military diplomacy in 2013. The PLAN was involved of six of them, demonstrating its growing diplomatic role.181 Perhaps this is not surprising: From 2002-12, nineteen of forty-one joint training activities conducted by China’s military involved the PLAN.182 In early 2014, the same website also noted the “top ten pieces of PLAN news in 2013,” in which the 5th anniversary of anti-piracy escorts ranked eighth.183 These highlights are parallel to broader outward engagement on the part of China’s military, which had conducted 17 different joint exercises and trainings with foreign armies in 2013 as of November that year.184

Besides greatly enhancing China’s ability to handle pirates over the course of six-plus years, China has progressively expanded the operational umbrella of PLAN anti-piracy task forces to include more diplomatic activities. In particular, with each successive task force sent to the Gulf of Aden, China’s Navy has pursued more friendly visits at regional ports in Africa, Asia, Europe and the Middle East. Apparently PLAN planners were initially concerned that local opposition might arise following Chinese port calls, though clearly this has not been an issue.185 While many visits are focused on the real needs of PLAN surface vessels and crewmembers such as refueling and replenishment, a growing ratio of port calls are dedicated to friendly visits between China and littoral states. Exhibit 3 underscores these trends, listing a selection of PLAN port calls since 2009 conducted under the aegis of anti-piracy.

EXHIBIT 3: PLAN Anti-Piracy Task Force Port Calls 2009-15 (Selected)

ALGERIA

Algiers

• April 2-5, 2013, Friendly Visit

ANGOLA

Luanda

• June 5-7, 2014, Friendly Visit

AUSTRALIA

Sydney

• December 18-22, 2012, Friendly Visit

BAHRAIN

Al Manamah

• December 9-13, 2010, Friendly Visit

BULGARIA

Varna

• August 6-10 2012, Friendly Visit

BURMA (MYANMAR)

Rangoon

• August 29-September 2, 2010, Friendly Visit

CAMEROON

Douala

• May 30-June2, 2014, Friendly Visit

DJIBOUTI

Djibouti

• January 24, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• May 3, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 13, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 22, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• December 24, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• February 21, 2011 Replenish/Overhaul

• October 5, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• March 24-29, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• May 14, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• August 13-18,2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• December 1-6, 2012 Replenish/Overhaul

• June 6-8, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• July 28, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• October 7-9, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• February 22-26, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 1-5,2014, Replenish/Overhaul and Friendly Visit

• June 30- July 4, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 8-12, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• November 3-7, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• January 25-30, 2015, Replenish/Overhaul

EGYPT

Alexandria

• July 26-30, 2010, Friendly Visit

FRANCE

Toulon

• April 23-27, 2013, Friendly Visit

• February 10-13, 2015, Friendly Visit

GERMANY

Hamburg

• January 19-24, 2015, Friendly Visit

GREECE

Crete

• March 7, 2011, Replenishment/Overhaul

Piraeus

• August 9-13, 2013, Friendly Visit

• February 17-20, 2015, Friendly Visit

INDIA

Cochin

• August 8, 2009, Friendly Visit

INDONESIA

Jakarta

• December 27-31, 2010, Friendly Visit

IRAN

Bandar Abbas

• September 20-24, 2014, Friendly Visit

ISRAEL

Haifa

• August 14-17, 2012, Friendly Visit

ITALY

Taranto

• August 2-7, 2010 Joint Drills and Friendly Visit

IVORY COAST

Abidjan

• May 20-22, 2014, Friendly Visit

JORDAN

Akada

• September 1-4, 2014, Friendly Visit

KENYA

Mombasa

• January 2-5, 2014, Friendly Visit

KUWAIT

Shuwaikh

• November 27 - December 1, 2011, Friendly Visit

MALAYSIA

Port Klang

• December 6, 2009, Friendly Visit

MALTA

• March 26-30, 2013, Friendly Visit

MOROCCO

Casablanca

• April 9-13, 2013, Friendly Visit

MOZAMBIQUE

Maputo

• March 29-April 2, 2012, Friendly Visit

NAMIBIA

Walvis Bay

• June 11-13, 2014, Friendly Visit

NETHERLANDS

Rotterdam

• January 26-29, 2015, Friendly Visit

NIGERIA

Lagos

• May 24-27, 2014, Friendly Visit

OMAN

Muscat

• December 1-8, 2011, Friendly Visit

Salalah

• June 21-July 1, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• August 14, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• January 2, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 1, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• June 8, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• August 10, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• January 19, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• January 28, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 10, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• June 23, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• August 8-11, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• November 7-10, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• February 21-24, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• July 1-3, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• July 9, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• March 28-29, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 16-19, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• May 11-13, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• October 6-9, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• November 3-7, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

PAKISTAN

Karachi

• August 5-8, 2009, Joint Drills and Friendly Visit

• March 7-13, 2010, Joint Drills and Friendly Visit

• March 13, 2011, Joint Drills

• September 8, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 27- October 31, 2014, Friendly Visit

PHILIPPINES

Manila

• April 13-17, 2010, Friendly Visit

PORTUGAL

Lisbon

• April 15-19, 2013, Friendly Visit

QATAR

Doha

• August 2-7, 2011, Friendly Visit

ROMANIA

Constanta

• July 31 - August 3, 2012, Friendly Visit

RUSSIA

Novorossiysk

• May 8-12, 2015, Friendly Visit

SAUDI ARABIA

Jiddah

• November 27-31, 2010, Friendly Visit

• September 3, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul

• June 17, 2012, Replenish/Overhaul

• January 1-6, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 25-28, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 14-18, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

• November 2-6, 2013, Replenish/Overhaul

SENEGAL

Dakar

• May 14-16, 2014, Friendly Visit

SEYCHELLES

Port of Victoria

• April 14, 2011, Friendly Visit

• June 16-20, 2013, Friendly Visit

SINGAPORE

Changi

• September 5-7, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul and Joint Drills

• December 18-20, 2011, Replenish/Overhaul and Friendly Visit

• September 5-10, 2013, Friendly Visit

• October 11-13, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul and Friendly Visit

SOUTH AFRICA

Cape Town

• June 17-20, 2014, Friendly Visit

Durban

• April 4-8, 2011, Friendly Visit

SRI LANKA

Colombo

• January 5-7, 2010, Friendly Visit

• December 7-12, 2010, Friendly Visit

• August 1-4, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 7-14, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul (Submarine & supply ship)

• October 13-18, 2014, Replenish/Overhaul (Submarine & supply ship)

Trincomalee

• January 13-15, 2014, Friendly Visit

TANZANIA

Dar es Salaam

• March 26-30, 2011, Joint Drills and Friendly Visit

• December 29, 2013-January 1, 2014, Friendly Visit

THAILAND

Sattahip

• August 16-21, 2011, Joint Drills and Friendly Visit

• April 21-25, 2012, Friendly Visit

• September 12-16, 2013, Friendly Visit

TUNISIA

La Goulette

• May 5-7, 2014, Friendly Visit

TURKEY

Istanbul

• August 5-8, 2012, Friendly Visit

UKRAINE

Sevastopol

• July 31-August 3, 2012, Friendly Visit

UNITED ARAB EMIRATES

Abu Dhabi

• March 24-28, 2010, Friendly Visit

• September 14-18, 2014, Friendly Visit

UNITED KINGDOM

Portsmouth

• January 12-16, 2015, Friendly Visit

VIETNAM

Ho Chi Minh City

January 13, 2013, Friendly Visit

YEMEN

Aden

• February 21, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• April 25, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• July 23, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• September 28, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• October 24, 2009, Replenish/Overhaul

• February 5, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• March 14, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• May 16, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• July 26, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• October 1, 2010, Replenish/Overhaul

• March 29-April 3, 2015, NEO

Note: Visit times, purposes, etc. may not be completely accurate or comprehensive. Replenishment/overhaul cases are particularly easy to miss since they are not always reported at the same levels of frequency as friendly visits. Some dates were calculated automatically based on length of port calls.

China’s 15th escort task force deployment, consisting of guided missile frigate Hengshui, comprehensive supply ship Taihu and amphibious landing ship Jinggangshan, offers a prime example of how anti-piracy escorts serve as a springboard for larger PLAN initiatives. In addition to training, at-sea replenishment and foreign port calls, the task force engaged with warships from Combined Task Force (CTF)-151, NATO, EU NAVFOR and the Ukrainian Navy, while also visiting Tanzania, Kenya and Sri Lanka following the end of its escort duties.186

China has combined port call diplomacy with a range of other creative contributions to international security made possible by its Gulf of Aden deployment. Simultaneously, China’s anti-piracy escorts complement broader economic and security engagement with African and Middle Eastern states arguably most affected by the scourge of piracy—including Somalia’s southwestern neighbor Kenya. For example, China is reportedly helping modernize the Kenya Defence Forces (KDF) to improve continental and maritime border security. In early January 2014, Governor Hassan Joho of Mombasa, Kenya’s largest coastal city, remarked to the visiting PLAN 15th escort task force, “We shall be looking for additional support from our friends from China to expand and build new roads, construct an efficient commuter railway network as well as provide adequate water and power for industries and households.”187 Previously, in January 2014, the 15th escort task force visited Tanzania, where it held an opening day activity with over 1,000 people, and also worked with Tanzanian naval personnel on warship maintenance and marine training.188

The fact that many Chinese citizens overseas, often including the resident ambassador, attend PLAN port call ceremonies carrying larger diplomatic messages underscores the broader role of PLAN overseas visits under the anti-piracy aegis. This reality was demonstrated by the 15th escort task force’s visit to Mombasa, Kenya in January 2014, where Chinese ambassador to Kenya Liu Guangyuan remarked, “Today, the visit to Mombasa by the Chinese Navy escort fleet has the same character with Zheng He’s voyages 600 years ago. It is a journey of peace, friendship and cooperation. The fleet comes not only with China’s solemn promise to safeguard world peace, but also with the sincere friendship from Chinese people to Kenya people.” Underscoring the larger significance of the PLAN’s visit, he also stated, “The visit is also a part of the celebrations marking the 50th anniversary of the establishment of diplomatic ties between China and Kenya.”189

More recently, Algeria, where PLAN anti-piracy forces previously docked in April 2013, announced plans to receive three Chinese frigates by 2015.190 The frigates are reportedly similar to those built by Pakistan with Chinese technological assistance, the last of which was completed in 2013. China and Ethiopia have jointly discussed fighting nontraditional threats such as terrorism and piracy.191 In September 2013 at the United Arab Emirates (UAE)-hosted Marine Counter Piracy Conference, Somalia’s president lauded China for its fight against piracy that creates $18 billion in economic losses for the IOR annually.192

Broad themes of cooperation and naval diplomacy notwithstanding, PLAN anti-piracy operations have also yielded modest but meaningful achievements in operational coordination with other navies. In October 2013 the PLAN showcased its flexibility in coordinating operations with other navies when the China Maritime Search and Rescue Centre (CMSRC) relayed a call for assistance from Taiwan merchant ship Guihua to Chinese frigate Hengshui. China published real-time location data about Guihua that was accessible to EU NAVFOR ships while Hengshui departed to replace a South Korean naval vessel no longer able to escort Guihua as a result of a “sudden failure” and because it was already scheduled to conduct a separate escort. Hengshui then proceeded to join Guihua and escort it safely to Port Aden.193

•

The PLAN’s six-plus-year presence off Somalia has helped increase the military’s overall strength in terms of operations, coordination and creativity. While the precise extent is unclear, it has also helped thrust the navy into a more prominent role within China’s larger security apparatus. A PLAN official commented to one of the authors that within domestic strategic circles, China’s development of maritime, maritime security and maritime development strategies are among the most frequently discussed topics. Specifically, in official parlance: how can China become a maritime great power through peaceful development in line with international norms, a harmonious society and environmental sustainability? And, how can China achieve maritime great power status in a way different from the approach taken by states that became great naval powers during the previous century?

•

![]()

104 Roy Kamphausen, David Lai, and Travis Tanner, eds., Assessing the People’s Liberation Army in the Hu Jintao Era (Carlisle, PA: Army War College, 2014).

105 The authors thank Nan Li for insights in this paragraph.

106 "China Mulls Revamping Military Regions to Boost Superiority in South and East China Seas,” Agence France-Presse, January 1, 2014, http://sg.news.yahoo.com/china-mulls-revamping-military-regions-japan-report-080327249.html.

107 Yang Yi, “New Joint Command System ‘On Way,’” Xinhua, January 3, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-01/03/c_133015371.htm.

108

![]() [Tao Shelan], “

[Tao Shelan], “

![]() ” [Chinese Military Clarifies “Establishing a Joint Operational Command": Has No Evidence],

” [Chinese Military Clarifies “Establishing a Joint Operational Command": Has No Evidence],

![]() [China News Agency], January 5, 2014, http://news.cnr.cn/native/gd/201401/t20140105_514574004.shtml.

[China News Agency], January 5, 2014, http://news.cnr.cn/native/gd/201401/t20140105_514574004.shtml.

109 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015 (Arlington, VA: Department of Defense, May 8, 2015), p. 1.

110 Authors’ discussion with Nan Li.

111 Yang Yi, “New Joint Command System ‘On Way,’” Xinhua, January 3, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-01/03/c_133015371.htm.

112

![]() [Academy of Military Science Strategic Research Department],

[Academy of Military Science Strategic Research Department],

![]() [The Science of Military Strategy] (Beijing:

[The Science of Military Strategy] (Beijing:

![]() [Military Science Press], 2013), pp. 262-63, 270.

[Military Science Press], 2013), pp. 262-63, 270.

113 “Chinese Navy Uses Telemedicine in Major Missions,” People’s Daily Online, January 7, 2013, english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8080783html.

114 For Beidou details, see Kevin Pollpeter, Patrick Besha and Alanna Krolikowski, “The Research, Development and Acquisition Process for the Beidou Navigation Satellite Programs,” in Kevin Pollpeter, ed., Getting to Innovation: Assessing China’s Defense Research, Development and Acquisition System (La Jolla, CA: University of California Institute on Global Conflict and Cooperation, January 2014), pp. 57-61, https://escholarship.org/uc/item/3p05b9xp.

115

![]() [Zhang Qingbao], “‘

[Zhang Qingbao], “‘

![]() ’—

’—

![]() ” [Overseas Economic Interests”: An Interview with Director General Ju Chengzhi of the International Cooperation Department under the Ministry of Transportation], People’s Navy, January 9, 2009, p. 4.

” [Overseas Economic Interests”: An Interview with Director General Ju Chengzhi of the International Cooperation Department under the Ministry of Transportation], People’s Navy, January 9, 2009, p. 4.

116 “Chinese Naval Escort Task force Repels 4 Suspicious Vessels,” China Military Online, January 15, 2014, http://www.360doc.com/content/14/0115/14/363711_345466711.shtml.

117 Chen Dianhong and Mi Jinguo, “11th Chinese Naval Escort Task force Holds Communication Drill,” China Military Online, June 28, 2012, http://english.people.com.cn/102774/7858609.html.

118

![]() [Wang Zhiqiu] and

[Wang Zhiqiu] and

![]() [Hou Rui], “

[Hou Rui], “

![]() ” [Pickup in the Gulf of Aden: Real Account of the Twelfth Naval Escort Task Force Warship Changzhou’s Pickup and Escort of Shiuh-fu 1 Fishing Boat Crew Members],

” [Pickup in the Gulf of Aden: Real Account of the Twelfth Naval Escort Task Force Warship Changzhou’s Pickup and Escort of Shiuh-fu 1 Fishing Boat Crew Members],

![]() [General News], People’s Navy, July 2012, p.3.

[General News], People’s Navy, July 2012, p.3.

119 Peng Yining, “Navy Lauded for Foiling Pirates,” China Daily, December 26, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8495596.html.

120 “China’s Eleventh Escort Fleet Returns from Somali Waters,” Xinhua, 13 September 2012, news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2012-09/13/c_131848762.htm.

121

![]() [Li Jianwen], “

[Li Jianwen], “

![]() 3000

3000

![]() ” [For the Harmony and Safety of the Golden Waterway: Written at the Time of the 3,000th Escort Breakthrough by Naval Escort Task Forces of Chinese and Foreign Ships], Liberation Army Daily, December 4, 2010, p.4, www.chinamil.com.cn/jfjbmap/content/2010-12/04/content_44927.htm.

” [For the Harmony and Safety of the Golden Waterway: Written at the Time of the 3,000th Escort Breakthrough by Naval Escort Task Forces of Chinese and Foreign Ships], Liberation Army Daily, December 4, 2010, p.4, www.chinamil.com.cn/jfjbmap/content/2010-12/04/content_44927.htm.

122 “Eleventh Chinese Naval Escort Task Force Realizes Scientific Escort,” China Military Online, May 5, 2012, eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2012-05/08/content_4855639.htm.

123 “Ninth Escort Formation of PLA Navy Deploys SOF Soldiers on Board MVs to Keep the Charge Perfectly Safe,” Military Report, CCTV-7 (Mandarin), October 19, 2011.

124 Zhao Shengnan, “Navy Protects Ships from Pirates,” China Daily, December 29, 2012, europe.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2012-12/29/content_16066937.htm.

125 “Conversation with Yin Zhuo: Escorts Are an Epoch-Making Event,” Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2011), p. 22.

126 “PLA Navy’s Tenth Escort Formation Provides On-Board Escort for Merchant Vessels for the First Time,” Military Report, CCTV-7 (Mandarin), 1130 GMT, November 28, 2011.

127 Kenneth Allen, “PLA Foreign Relations under Xi Jinping: Continuity and/or Change?” paper presented at the Chinese Council on Advanced Policy Studies (CAPS)-RAND-National Defense University 26th Annual PLA Conference, Arlington, VA, November 21-22, 2014.

128

![]() [Yao Jiang],

[Yao Jiang],

![]() [Lu Wenjie] and

[Lu Wenjie] and

![]() [Lu Wenqiang], “

[Lu Wenqiang], “

![]() ” [Holding Up Warships Rushing into the Big Ocean: Equipment Support is Effective in Navy’s Open-Ocean Shipping Protection Effort], People’s Navy, July 3, 2012, p. 3.

” [Holding Up Warships Rushing into the Big Ocean: Equipment Support is Effective in Navy’s Open-Ocean Shipping Protection Effort], People’s Navy, July 3, 2012, p. 3.

129

![]() [Chen Guoquan] and

[Chen Guoquan] and

![]() [Zhang Xin], “

[Zhang Xin], “

![]() ” [Navy Will Continue to Send Troops to Escort], Liberation Army Daily, December 27, 2013, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2013-12-27/0500757043.html.

” [Navy Will Continue to Send Troops to Escort], Liberation Army Daily, December 27, 2013, http://mil.news.sina.com.cn/2013-12-27/0500757043.html.

130 “Chinese Navy Escort Task force Starts Mission at Gulf of Aden,” Xinhua, August 27, 2013, http://www.globaltimes.cn/DesktopModules/DnnForge%20-%20NewsArticles/Print.aspx?tabid=99&tabmoduleid=94&articleId=806621&moduleId=405&PortalID=0.

131 “South China Sea Fleet Unveils New Round of Long Voyage Training,” Liberation Army Daily, December 20, 2013, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/TopNews/2013-12/20/content_4480189.htm.

132 “Chinese Naval Escort Task force Conducts Anti-Piracy Training,” Liberation Army Daily, February 27, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8146977.html.

133

![]() [Guang Wen], “

[Guang Wen], “

![]() ” [Near Seas Protector: Towards the PLA Navy’s Type 056 New Frigate],

” [Near Seas Protector: Towards the PLA Navy’s Type 056 New Frigate],

![]() [Shipborne Weapons], No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 26-29.

[Shipborne Weapons], No. 1 (January 2011), pp. 26-29.

134

![]() [Wang Jin], “

[Wang Jin], “

![]() ” [New Era, New Missions: The PLA-Navy’s Type 056 Light Frigate], Shipborne Weapons, No. 8 (August 2012), pp.18-21.

” [New Era, New Missions: The PLA-Navy’s Type 056 Light Frigate], Shipborne Weapons, No. 8 (August 2012), pp.18-21.

135 “Shanghai Commissions Large Patrol Vessel,” Xinhua, April 17, 2013, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2013-04/17/content_16413011.htm. For documentation of similar capabilities deployed in China’s consolidating Coast Guard, see Ryan Martinson, “Here Comes China’s Great White Fleet,” The National Interest, October 1, 2014, http://nationalinterest.org/feature/here-comes-china%E2%80%99s-great-white-fleet-11383.

136 The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), p. 14.

137 Ibid, p. 15.

138 Military Report, CCTV-7 (Mandarin), 1130 GMT, March 19, 2013.

139 Li Jie, “A New Milestone in Going to the Ocean,” Five Year Escort Special Column, Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2013), p. 20.

140 J. Michael Cole, “New Chinese Ship Causes Alarm,” Taipei Times, March 31, 2012, http://www.taipeitimes.com/News/front/archives/2012/05/31/2003534139.

141 The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), p. 15.

142 Ibid.

143 The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), p. 17.

144 For a survey of Chinese UUV research and development, see Lyle Goldstein and Shannon Knight, “Coming without Shadows, Leaving without Footprints,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 136, No. 4 (April 2010), pp. 30-35.

145 The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), p. 19.

146 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015, Annual Report to Congress (Arlington, VA: Office of the Secretary of Defense, May 8, 2015), p. 19.

147 Dong Zhaohui, ed., “PLA Navy Submarine visits Sir Lanka,” China Military Online, September 24, 2014, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2014-09/24/content_6152669.htm.

148 Jeremy Page, “Deep Threat: China’s Submarines Add Nuclear-Strike Capability, Altering Strategic Balance,” Wall Street Journal, October 24, 2014, http://online.wsj.com/articles/chinas-submarine-fleet-adds-nuclear-1414164738?tesla=y&mg=reno64-wsj.

149 Cdr. Gurpreet Khurana, Cdr. Kapil Narula and Asha Devi, “PLA Navy Submarine Visits Sir Lanka,” Making Waves, Vol. 19, No. 9.2 (New Delhi: National Maritime Foundation, September 30, 2014), p. 37, http://maritimeindia.org/pdf/MW%209.2(Final).pdf.

150 David Tweed, “China’s Clandestine Submarine Caves Extend Xi’s Naval Reach,” Bloomberg, October 31, 2014, http://www.bloomberg.com/news/2014-10-30/xi-s-clandestine-submarine-caves-bolster-china-s-maritime-goal.html.

151 Shihar Aneez and Ranga Sirilal, “Chinese Submarine Docks in Sri Lanka Despite Indian Concerns,” November 2, 2014, http://in.reuters.com/article/2014/ll/02/sri-lanka-china-submarine-idINKBN0IM0LU20141102.

152 For details, see “

![]() ” [‘In the Gulf of Aden’ Sets Sail from CCTV Tonight: Zhong Lei Plays Chivalrous Role], Xinhua, September 3, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/ent/2014-09/03/c_126951244.htm.

” [‘In the Gulf of Aden’ Sets Sail from CCTV Tonight: Zhong Lei Plays Chivalrous Role], Xinhua, September 3, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/ent/2014-09/03/c_126951244.htm.

120 Episodes of “

![]() ” [In the Gulf of Aden] maybe viewed at “

” [In the Gulf of Aden] maybe viewed at “

![]() ,” http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLI5Y-oBlN4-zytZ3a_deUXcM_3CSVefaK.

,” http://www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLI5Y-oBlN4-zytZ3a_deUXcM_3CSVefaK.

154 CCTV-7 report, as documented frame-by-frame in “

![]() 091

091

![]() ” [First Official Media Exposure of Modified PLAN Type 091 Nuclear—Powered Attack Submarine in Gulf of Aden],” Xinhua Net, April 27, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2015-04/27/c_127736846.htm.

” [First Official Media Exposure of Modified PLAN Type 091 Nuclear—Powered Attack Submarine in Gulf of Aden],” Xinhua Net, April 27, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/mil/2015-04/27/c_127736846.htm.

155 “

![]() ” [Hong Kong Media: CCTV Offers First Exposure of Modified 091 Nuclear Submarines-Normalization of Gulf of Aden Escorts],

” [Hong Kong Media: CCTV Offers First Exposure of Modified 091 Nuclear Submarines-Normalization of Gulf of Aden Escorts],

![]() [Global Net], April 29, 2015, http://military.people.com.en/n/2015/0429/cl011-26923066.html.

[Global Net], April 29, 2015, http://military.people.com.en/n/2015/0429/cl011-26923066.html.

156 “Getting Close to a Submarine Detachment of the PLA Navy,” People’s Daily Online, May 7, 2015, http://english.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2015-05/07/content_6478476.htm.

157 Andrew S. Erickson and Austin M. Strange, “Learning the Ropes in Blue Water: The Chinese Navy’s Gulf of Aden Deployments Have Borne Worthwhile Lessons in Far-Seas Operations—Lessons that Go Beyond the Anti-piracy Mission,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, Vol. 139, No. 4 (April 2013), pp. 34-38.

158 Ai Yang, “Navy Beefs Up Anti-Piracy Effort,” China Daily, March 24, 2010, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2010-03/04/content_9534852.htm.

159 For details, see Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Naval Modernization: The Implications of Seapower,” World Politics Review, September 23, 2014, http://www.worldpoliticsreview.com/articles/14083/chinas-naval-modernization-the-implications-of-seapower.

160 David Liebenberg and Jeffery Becker, “Recent Personnel Shifts Hint at Major Changes on the Horizon for PLA Navy Leadership,” Jamestown Foundation China Brief, Vol. 14, No. 3, February 7, 2014, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=41937&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=25&cHash=6596e44f8d7d62e11038e307359acaea#.UvyMwyuf-LE.