VII. Gulf of Aden Operations and China’s Future Far Seas Presence

“After decades of development, the PLA Navy now has the capability to provide protection in far seas,” declared PLA NDU Professor Guo Fenghai in December 2013.194 Guo’s statement echoes the sentiment of many PLAN officials who laud the Gulf of Aden as a valuable stepping-stone for the PLAN into a more permanent Far Seas presence. Given Beijing’s long-time absolutist position on sovereignty and traditional reluctance to participate in international missions, this is indeed a veritable sea change. China’s well-documented verbal and (often) operational commitment to noninterference in the affairs of other states has increasingly evolved into a focal point of discussions about the future of Chinese foreign policy inside and outside of China. While many believe China’s approach is undergoing gradual adjustment and recalibration commensurate with its increasing relative stature in international economic and security affairs, to date there are still relatively few prominent, conspicuous manifestations of this transition, making China’s presence off Somalia all the more meaningful.

Indeed, the mission has driven a drastic increase in blue water diplomacy in the name of fighting piracy, and has prompted growing calls for a more regularized Far Seas presence. In particular, it yields several insights about China’s evolving global maritime presence and its implications for Chinese naval development:

• First, anti-piracy operations have been a springboard for China to progressively engage in a broader range of maritime security operations.

• Second, China’s increasingly comprehensive blue water pedigree will have a larger influence on overall PLAN growth.

• Third, the eventual conclusion of international anti-piracy operations in the Gulf of Aden and off Somalia will create challenges for China’s Navy as it attempts to maintain and bolster its international maritime presence.

• Fourth, the motivations for continuing to deploy anti-piracy task forces suggest that Beijing will work to institutionalize its future role in global maritime security.

• Finally, more than six years of anti-piracy operations thousands of km from China have spurred Chinese discussions of more permanent overseas access points to better protect external interests.

Of course, Chinese strategists also understand the limits of Beijing’s political and military efforts to protect overseas Chinese interests, which undoubtedly factors into China’s calculus on how to design its future Far Seas presence. For example, Li Ruijing of the PLA AMS states that anti-piracy operations by China’s Navy are inadequate for protecting Chinese interests comprehensively, particularly those that are smaller and more localized. Li argued that China would need private security contractors to fill this gap: “As exemplified by [the] U.S. [company] ‘Blackwater,’ by establishing and strengthening [the] Chinese ‘Red Shield,’ thereby letting Chinese civil security go abroad, escorts can develop to the highest degree and protect China’s overseas interests.”195

Li’s vision for Chinese private security is already materializing, with the private sector offering security solutions, albeit to a very limited extent. In 2013, Qi Luyan, who had founded Huawei International Security Management four years before, stated: “China’s security industry will definitely grow like China’s other industries, because Chinese citizens and assets overseas are frequently threatened.”196 ZTE Corp. has employed local guards in Pakistan, while Chinese energy companies have retained Western private security firms in Iraq.197 Shandong Huawei Security Group hires former Chinese special forces. Genghis Security Academy offers bodyguard protection overseas. Huaxin Zhong’an even dispatched armed security personnel on Chinese commercial vessels in the Gulf of Aden for the first time in March 2012, some of whom had previously served there in the PLAN.198 Special Fighters (China) International Security Service Group, China Kingdom International and Genghis VIP Protection also headline the quickly emerging industry in China.199 However, Western firms continue to dominate this market and it remains unclear how much share Chinese challengers can acquire in the near term.200 Former Blackwater CEO Erik Prince is positioning his new Hong Kong-based Frontier Services Group to provide logistics and security for Chinese operations in Africa.201

•

One Far Seas Mission Begets Another

China’s Gulf of Aden presence has supported various Chinese contributions to international security in the years since 2008. The PLAN has continuously aided UN WFP vessels by escorting them through pirate-infested waters off Somalia en route to Africa. China does not discriminate when escorting commercial ships, as it has provided protection for Western-flagged ships, as well as ships belonging to autocratic regimes such as North Korea.202

In 2011, China dispatched the guided missile frigate Xuzhou from its escort duties in the Gulf of Aden to provide security during the evacuation of overseas Chinese citizens from Libya. Other Chinese naval vessels venturing into the Far Seas have also earned goodwill made possible by China’s anti-piracy presence. In July 2013, the Chinese hospital ship Peace Ark conducted a 15-day operation in the Gulf of Aden. In addition to providing an array of medical services to citizens of eight different countries during its IOR goodwill visit, Peace Ark crewmembers also conducted medical exchanges with foreign naval medical counterparts,203 as well as with foreign naval officers more broadly.204

More recently, PLAN guided missile frigate Yancheng of the 16th escort task force temporarily halted its anti-piracy escort duties to participate in a multilateral escort mission of Syrian chemical weapons across the Mediterranean Sea. By early February 2014, Yancheng had completed three escorts of Danish and Norwegian ships stocked with chemicals in coordination with a Russian warship. The navies of China and Russia have also conducted patrols and surveillance activities in assigned areas outside Syria’s main port Latakia (al-Lādhiqīyah) to ensure a stable environment for transporting the weapons away from Syria to their destruction.205 China’s Foreign Ministry spokeswoman Hua Chunying declared in early February 2014 that the PLAN was committed to continued support for chemical weapons removal, and escorts were completed on June 23, 2014.206

Chinese media outlets have lauded Yancheng’s contributions in the Mediterranean, which began in the aftermath of China’s declaration of an Air Defense Identification Zone (ADIZ) in the East China Sea, which was highly controversial in its roll out.207 Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi initially declared China’s willingness to support the mission in late 2013.208 Xi Jinping personally sent greetings to Yancheng and its crew after the Chinese New Year.209 Meanwhile, Chinese military officials and academics such as PLAN Naval Military Studies Institute Deputy Director Zhang Junshe said that China’s role in escorting chemical weapons reflects the international community’s recognition of the PLAN’s growing escort capabilities, and presents China’s Navy with a new venture in a relatively new region.210

The PLAN is increasingly adept at maximizing Far Seas value without bases by creatively pursuing complementary opportunities. In early 2014, Russia’s Ministry of Defense announced that Russian nuclear missile cruiser Peter the Great and Yancheng would hold joint rescue and anti-terrorism drills in the Mediterranean Sea following their collaborative escorts of ships carrying Syrian weapons.211 Given that China’s coastline is about 10,000 km from the Gulf of Aden, and even further from the Mediterranean, such contributions to security in this increasingly vital region would likely be far more limited if China had not deployed warships to the Gulf of Aden in 2008.

More recently, the PLAN demonstrated the options that maintaining anti-piracy operations in the Far Seas affords by helping escort Chinese and foreign nationals from Yemen following the outbreak of violent civil war. On March 29, 2015, all three PLAN vessels from the 19th task force halted anti-piracy escort operations for 109 hours to evacuate Chinese and foreign nationals from the port of Aden.212 That day, frigate Linyi evacuated 122 Chinese nationals. On March 30, missile frigate Weifang evacuated 449 Chinese nationals.213 Then, on April 2, one of the warships evacuated 225 foreign citizens from 10 countries.214 Both China’s timely response and its willingness to send its entire anti-piracy task force to the Yemeni coast reflect leverage offered by sustained nontraditional security operations in the area. This suggests a strategic challenge for Chinese naval planners looking to maintain or even boost China’s global maritime security presence once Gulf of Aden operations come to an eventual conclusion.215

On May 11, 2015, the navies of China and Russia began a ten-day joint exercise called “Joint Sea-2015” in the southern Russian city Novorossiysk on the Black Sea. The drills included six Russian warships, and were focused on “maritime defense, replenishment and escorting.”216 The PLAN dispatched three ships from its 19th escort task force, namely Linyi, Weifang and Weishanhu, to participate. After leaving Novorossiysk, the nine warships conducted live-fire and other joint exercises in the Mediterranean Sea, seen by both sides as an increasingly strategic waterway. While modest in scale, the exercises offer yet another example of how Beijing has squeezed additional value out of its anti-piracy operations.

ONI judges that China’s “commitment and ability to sustain its counterpiracy operations in the Gulf of Aden indicates Beijing’s dedication to pursuing diversified military tasks around the world. We expect this trend will continue or even expand as new security challenges provide opportunities for international operations.”217

•

A New Player in the Global Maritime Commons

China’s Gulf of Aden security contributions from 2008-15 and beyond herald China’s irreversible entrance into global maritime security as a meaningful player. Given that trends in the Yellow, East and South China Seas remain increasingly negative in terms of their impact on China’s international image, one can argue that China needs to pursue creative options that will strengthen its identity as a responsible stakeholder in international society, particularly in the maritime domain. China’s response to humanitarian assistance and disaster relief in the aftermath of Typhoon Haiyan exemplifies the competing interests it must juggle in formulating policies concerning Near Seas neighbors. China’s initial contribution of $100,000 upset many domestic and international commentators, although it subsequently boosted donations to over $1 million while also dispatching in-kind goods as well as hospital ship Peace Ark to help the Philippines.218 China’s perceivably meager contribution came in stark contrast to other nations such as the United States, which donated over $86 million in food aid, shelter materials, clean water and hygiene education.219

The Gulf of Aden mission affords Beijing significant opportunities to project a positive image. Wei Xueyi, commander of the 6th escort task force, calls for PLAN escorts to “display an image of China being a responsible power.”220 Chinese leaders are learning, however, that success comes with inflated expectations on the international stage. This reality makes China’s inevitable exit from the Gulf of Aden all the more interesting in the context of Beijing’s future IOR role, which many analysts believe will grow in the coming years.221 It also poses similar questions for China’s future role in Middle Eastern, North African and Mediterranean maritime security.222

Certainly, there is another side to the debate about how anti-piracy escorts in the Gulf of Aden impact China’s foreign policy. For instance, others have pointed out that by deploying large surface vessels to the Far Seas, and traversing Southeast Asia and the IOR in the process, Asian militaries such as China and Japan may be drawing the ire of neighboring Southeast Asian states unlikely to welcome the increase in military traffic near their borders.223 Of course, these littoral states do not necessarily have much choice in the matter.

•

How Long at Sea? Projecting the Remainder of PLAN Anti-Piracy Operations

On November 12, 2014, the UNSC extended its mandate for state navies to fight piracy off Somalia for an additional twelve months and into November 2015. Based on its previous behavior, China is likely to remain contributing PLAN resources to the international anti-piracy effort there. “As long as Gulf of Aden pirate activities continue, so too will the escort operations of international navies,” Admiral Wu Shengli declared in September 2014. “So far, there is no end in sight for the mission.”224 November 2015 is currently the latest date that the UNSC legally mandates navies to operate there. As this study went to press, there had been no explicit announcement by the PLAN or any other official Chinese policymaking agencies of when China’s Gulf of Aden mission would cease.

For now, China and others continue smothering Somali piracy in the Gulf of Aden. But these deployments will presumably end at some point. Reports in late 2012 that worldwide pirate attacks had “plummeted” reflected the success of anti-piracy operations by navies throughout the world. According to the International Chamber of Commerce (ICC) International Maritime Bureau (IMB) Piracy and Armed Robbery against Ships 2013 Annual Report, there were just seven actual and attempted pirate attacks off Somalia in all of 2013.225 From January–August 2014, there were only 17 attacks in the Gulf of Aden, none successful.226 Given the lack of a successful Somali pirate attack since 2012, it is important to consider the “Post-Aden” era of China’s Far Seas naval development. Presumably Chinese strategists are deliberating over if and when the PLAN should terminate its Gulf of Aden deployments, influenced in part by downward trends in Somalia piracy.

During a speech at the U.S. NDU in May 2011, PLA Chief of General Staff Chen Bingde suggested that China’s Navy might not be able to support the Gulf of Aden mission much longer. Discussing China’s deployment of naval power to protect the maritime commons in the shipbuilding costs and foreign reactions to China’s naval buildup, Chen acknowledged, “If the situation continues like this, it will create great difficulties for us to continue with such operations. Although the development of the Chinese PLAN has come a long way in recent years and we have developed a number of new ships... we are not that strong yet.”227

ONI reported in late 2013 that Somali pirates failed to pirate a single commercial vessel in the Indian Ocean successfully during 2013.228 Certainly, piracy and other nontraditional threats will not vanish entirely from the maritime commons. But the dramatic decline in Somali pirate attacks signifies meaningful gains made in this field by U.S.- and European-led multilateral anti-piracy forces, as well as “independent” contributors such as Russia and China. The very success of such collaboration, however, means that many states including China may soon lack a reason to keep large naval assets in the Gulf of Aden and surrounding waters.

However, this reduction is certainly not perceived by China or other states as signaling the eradication of this nontraditional security problem.229 In late 2013, Naval Command College Professor Qu Lingquan admonished Chinese not to avoid dismissing the threat of Somali piracy. Qu emphasized unpredictable increases and decreases in the frequency of attacks, as well as the expansion of pirate activities from a mere 200 nautical miles [370 km] to 1,750 nautical miles [3,241 km] and cunning tactics employed by Somali pirates as reasons to remain vigilant.230

Revelations in July 2014 that the Japan Maritime Self Defense Force (JMSDF) would assume command of CTF-151 added a new wrinkle to discussions about Beijing’s future role in international anti-piracy.231 Japan’s command is enabled by its reinterpretation of its constitution, and builds on a host of related developments including the seconding of a JMSDF officer to the Pentagon to enhance interoperability amid heightened Sino-Japanese tensions in the East China Sea.232 While it remains unclear how Chinese leaders have reacted to the CTF-151 announcement, it seems safe to assume that Beijing will not visibly reduce its presence at a time when Tokyo is taking its contributions to an unprecedented level. This is particularly true since JMSDF efforts will certainly be more impressive to Western navies than China’s parallel contributions in isolation, given the JMSDF’s willingness and ability to integrate directly with these navies and (at least by sensitive Chinese standards) assume operational command over them. Whatever plans it may have had for winding down Gulf of Aden operations in the near future, China has surely postponed them for now.

Nonetheless, China’s Navy must already be considering the costs and benefits of continued operations as progresses through a seventh year of continuous task force deployment.233 The PLAN’s learning curve in the Gulf of Aden has flattened progressively since 2008, which begs the question: Do the significant but largely abstract benefits of future escort task forces, or other forms of Far Seas anti-piracy operations, outweigh the many concrete costs? The most direct inputs include fuel, food, health equipment and supplies, ammunition and weaponry, auxiliary equipment as well as the expenditures associated with dispatching two to three large warships 10,000 km from China for six months at a time.

Like all other navies currently serving there, the PLAN will eventually conclude its Gulf of Aden anti-piracy operations. Even if China perceives the costs of the mission as beginning to overshadow the benefits, the PLAN could remain in the Gulf of Aden past China’s perceived point of diminishing marginal returns to avoid being perceived to shirk international responsibility. It may first wait until certain other navies withdraw before exiting the Gulf of Aden itself.

•

Naval Planning After Anti-piracy

The answers to these questions will offer significant insights into Beijing’s longer-term plans for the Chinese naval presence in the maritime commons. While the Gulf of Aden mission has been difficult for Beijing in some respects, particularly regarding logistical planning, given China’s lack of overseas basing infrastructure, the mission itself has served as a vital springboard for a more active Chinese naval engagement in the Far Seas. Once China departs the Gulf of Aden, its ability to respond to a myriad of security challenges, from evacuating Chinese citizens in Africa or the Middle East to providing military assets for UN-mandated international security operations such as the destruction of Syrian chemical weapons, will inevitably be compromised. It is thus probable that Chinese policymakers are considering various overseas access strategies for China’s military that could come into play post-Gulf of Aden involvement.

Of potentially equal importance is the loss of opportunities to learn from other navies in the Gulf of Aden. China primarily uses “shipborne radio station(s)” (

![]() ), “satellite phones” (

), “satellite phones” (

![]() ), “military data links” (

), “military data links” (

![]() ) and “the international Internet” (

) and “the international Internet” (

![]() ) to communicate with other navies in the region.234 Chinese naval leaders value the constant interactions with foreign navies that anti-piracy operations afford. And despite prideful statements by officials and experts, China harbors no illusions that its navy rules Gulf of Aden waters. As Ji Rongren declared:

) to communicate with other navies in the region.234 Chinese naval leaders value the constant interactions with foreign navies that anti-piracy operations afford. And despite prideful statements by officials and experts, China harbors no illusions that its navy rules Gulf of Aden waters. As Ji Rongren declared:

Currently among the escort forces in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters, three branches are the strongest: the task forces of EU NAVFOR, CMF [Combined Military Forces] and NATO. ...among [them], EU NAVFOR is the maritime force that has the most active and powerful escort and anti-piracy operation in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters. Given that 95 percent of the EU’s annual trade is seaborne, yet only 20 percent of this passes through the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters, one can see from this that safe navigation through this maritime area is very important to the EU. Starting in November 2007, NATO also began escorting ships carrying UN emergency assistance to Somalia; in March 2009 NATO again approved a combat plan for anti-piracy in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters. CMF was established earlier. [This] U.S.-led [coalition] of ships from multiple states [was established] in October 2001. [It] was already established when “Operation Enduring Freedom” (

![]() ) was initiated during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Twenty-three countries have subsequently participated [in CMF], Five years in the Gulf of Aden have showed, [through] initiating international escort cooperation in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters that fighting pirates jointly is the “trend of the times” (

) was initiated during the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Twenty-three countries have subsequently participated [in CMF], Five years in the Gulf of Aden have showed, [through] initiating international escort cooperation in the Gulf of Aden and Somali waters that fighting pirates jointly is the “trend of the times” (

![]() ); it’s easy to see that the effect of relying on just one state “going it alone” (

); it’s easy to see that the effect of relying on just one state “going it alone” (

![]() ) would be extremely limited.235

) would be extremely limited.235

Moreover, in addition to the economic, political and strategic costs and benefits discussed above, opportunity costs arise when one considers that certain landing ships and other assets could instead be training in the East or South China Seas. Alternatively, China may prefer to continue achieving incremental breakthroughs in the Gulf of Aden, where it can also test new platforms and systems, including indigenous ones such as the Z-9 helicopter.236 This argument is of course two-sided, since Gulf of Aden experience is apparently considered by PLAN leadership when choosing surface platforms to deploy in the Asia-Pacific and Indian Ocean. For example, in early February 2014 the PLAN’s SSF dispatched amphibious landing ship Changbaishan along with destroyers Haikou and Wuhan, both of which have extensive Gulf of Aden experience and are equipped with advanced weapon platforms, to perform anti-piracy, joint search and rescue and damage control training in the West Pacific after conducting similar drills in the Indian Ocean.237

Looking further ahead, if Gulf of Aden piracy does not reemerge as a sizable maritime nontraditional security threat to China’s national interests, and if the UN does not extend the international mandate for states to fight piracy at some point, then what is the future of PLAN anti-piracy operations? Can the PLAN justify a continued Gulf of Aden presence internally and externally? If even such justification is possible, do Chinese strategists perceive the economic, political and strategic benefits of a long-term naval presence in the Gulf of Aden as greater than its comprehensive costs? Given this larger context, might it not make sense for China to seek to deepen cooperation with other navies and international organizations to minimize its own expenses?

Given its role as a gateway to various Far Seas security contributions, as well as brewing tensions in the Near Seas, the Gulf of Aden mission and the void its completion may leave in the PLAN’s Far Seas presence creates challenges for Chinese policymakers. For example, since 2008 Beijing has consistently been able to offset arguably assertive, provocative actions in the Yellow, East and South China Seas with incremental contributions to maritime security in its Far Seas, including the Gulf of Aden. For instance, the announcement on December 17, 2013 that China would assist with chemical weapons escorts coincided with U.S. Secretary of Defense Chuck Hagel labeling China’s behavior during the “Cowpens Incident” in the South China Sea as “irresponsible.”238 While international goodwill and training missions by China’s Peace Ark hospital ship, search and rescue vessel Haixun 01 and other auxiliary platforms could be scaled up to fill the Gulf of Aden void, China’s Far Seas diplomacy could suffer in other ways. As the Libya and Syria cases demonstrate, China’s Gulf of Aden presence provides convenient access to Asia, Africa and Europe, as well as the Atlantic and Indian Oceans, even though China currently possesses no overseas bases. Given that during 2013 only a handful of pirate attacks (all failed attempts) occurred in the Gulf of Aden, compared to 31 in the Gulf of Guinea, suggests that China and other states may consider a greater role in the future of West African maritime security.239

The prospect of a future role for Beijing in Gulf of Guinea security is additionally intriguing, not only because of China’s development finance and trade activities in Gulf states, but also because it might be an ideal area for the United States and China to achieve mutually beneficial cooperation amidst a backdrop of growing Sino-U.S. strategic rivalry in Africa.240 That said, many other advanced navies, including the U.S. and several European navies, are arguably ahead of China in this region. For instance, the EU announced in 2013 that it was “developing a Gulf of Guinea strategy” composed mainly of auxiliary support rather than actual deployments of European naval ships.241

PLAN officials appear cautiously open-minded regarding Gulf of Guinea maritime security. In “a concerning trend for all world navies,” Admiral Wu acknowledged, new piracy challenges have emerged in the Gulf of Guinea.242 Another PLAN official suggests that “cooperation in the Gulf of Guinea might be possible in theory.” Another PLAN official told one of the authors: “Piracy is decreasing in the Indian Ocean Region, but increasing in other areas. China is considering cooperation with other nations in the Gulf of Guinea.” Yet another offered specific criteria:

“China can consider Gulf of Guinea deployment if its policy criteria are met—a UN resolution, support of local governments and PLAN capabilities. The last is particularly important, as the Gulf of Guinea is far further removed from China than the Gulf of Aden, and China lacks basing facilities in the region or even logistical experience. Moreover, the Gulf of Guinea is not a central SLOC in the way that the Gulf of Aden is. If China deploys to the Gulf of Guinea, it will do so on its terms and in its own interest, and not worry about U.S. views of what China should do.”

Additionally, potential engagement in the Gulf of Guinea, similar to the Gulf of Aden, highlights the diverse regional perspectives among naval powers likely to get involved. For example, as one PLAN official pointed out, while his service views the Gulf of Aden mission primarily as a “one off’ deal dependent on UN mandate as well as explicit local government support and invitation, the U.S. 5th Fleet has rich historical experience in the region and its presence there is not dependent on UNSC anti-piracy resolutions. Similarly, multiple European states enjoy an enduring presence in surrounding regions while India views the area on one of traditional Indian influence. In the Gulf of Guinea, China is also a newcomer in terms of historic involvement, particularly when compared to Europe and the United States. This is not to say that China is entirely absent in the Gulf’s present security framework, however. China has economic and security cooperation agreements with many littoral states there, and sells ships to regional coastguards and navies. For instance, Nigeria purportedly ordered to offshore patrol vessels (OPV) from China, one of which was commissioned in 2015 along with another patrol boat given by China.243 China’s liaison for SHADE from PLAN escort task forces 3-17 Sr. Col. Zhou Boenvisions substantial space for Sino-American cooperation on Gulf of Guinea anti-piracy.244

Besides serving as a platform for other Chinese security missions beyond the Asia-Pacific, Gulf of Aden experience has arguably provided Chinese naval planners with important guidance on how to structure China’s contributions to Far Seas maritime security while China develops into a maritime power. For example, as in the Gulf of Aden, China was comfortable with providing complementary, albeit parallel security contributions—rather than outright leadership—for the Syrian chemical weapons neutralization mission ordered by the UN. Cao Weidong of the Naval Military Studies Research Institute, the PLAN’s strategic think tank, asserts that Syrian chemical weapons escorts were similar to China’s ongoing anti-piracy escorts, and as such PLAN escort duties have already become a “walk in the park.”245 While Cao’s assessment of the operational aspects of the Syrian escort mission is plausible if hyperbolic, it would be difficult for Beijing to even participate in such activities in the first place without its Gulf of Aden presence, unless it pursues different forms of international footholds that can support a medley of military and paramilitary operations far from China’s island and maritime claims.

While China is actively expanding its international maritime cooperation, annual exercises and visits cannot replace the regularized forms of communication and coordination achieved by the PLAN in the Gulf of Aden. For instance, its historic official participation in U.S.-led Rim of the Pacific (RIMPAC) 2014 exercise, the largest regularly held international maritime exercise, which is held biannually, is a useful multi-week platform for engagement across a variety of fields. Four PLAN ships drilled on subjects such as anti-piracy with international counterparts off Hawaii.246 But RIMPAC is not regularized or high-intensity. On the other hand, as an active member of the SHADE coordination mechanism, China’s Navy has regularly coordinated its escorts with other “independent providers” such as India, Japan and South Korea through the Convoy Coordination Working Group (CCWG).247 Like China, each of these “independent providers” relies heavily on energy and commodity shipments through the Gulf of Aden and proximate waterways. Many of them have contributed substantial security resources off Somalia. For example, in January 2014 South Korea deployed its 15th anti-piracy task force from Busan Port, consisting of veteran destroyer Cheonghae and over 300 personnel, including Special Forces, an underwater demolition team, navy seals, marine and naval aviators.248 As a PLAN official told one of the authors, CCWG navies prefer to “escort merchant ships from point A to point B” rather than serve as “traffic police.” He allowed, “There are advantages and disadvantages to each approach.”

Besides convoy coordination, PLAN ships have previously “fill[ed] patrol gaps” left by Western navies. China’s Navy also communicates routinely with Western and other navies through the EU’s Mercury software as well as bridge-to-bridge radio. PLAN forces quickly adopted the former technology to communicate with CMF, EU and NATO ships because it is more secure than commercial e-mail services, and also allowed China to learn NATO-based nomenclature and procedures including code words used openly across Mercury.

China is, according to a Western SHADE representative whom one of the authors interviewed, “trying to validate its own contributions, but not to change the status quo.” There may be some effort to make adjustments at the edges, however. A PLAN official has stated before one of the authors that SHADE is “very important” (

![]() ), “but there is still some space for improvement.” Specifically, in his view, “two aspects need to be solved.” The first is “strategic cooperation,” or how the United States and China can establish a “balance of interests in the Indian Ocean. The United States should clearly recognize Chinese interests and the contributions to stability it has already made.” If the United States can recognize and acknowledge China’s interests in the Indian Ocean, he maintained, there will be more opportunities for cooperation between the two navies.

), “but there is still some space for improvement.” Specifically, in his view, “two aspects need to be solved.” The first is “strategic cooperation,” or how the United States and China can establish a “balance of interests in the Indian Ocean. The United States should clearly recognize Chinese interests and the contributions to stability it has already made.” If the United States can recognize and acknowledge China’s interests in the Indian Ocean, he maintained, there will be more opportunities for cooperation between the two navies.

The second is “lower-level cooperation,” including joint exercises and technical communication, i.e., through the commonly-used Channel 16 VHF.249 This area is relatively easy and simple: “Far away from [China’s] homeland, the U.S. and Chinese navies are friends.” Some aspects need to be improved, however, particularly regarding information exchange. Whereas the U.S. and EU navies exchange email daily, it was typical for the Chinese task force to receive “only three emails.” As for vessels under attack (VSL) lists, deployment sheets and weather conditions, “we need to do more in this field.”

The PLAN official believes deep antagonism still exists among officers and enlisted in the U.S. and Chinese navies. One day, for instance, a Chinese vessel conducted gunnery practice in the Gulf of Aden, causing a nearby U.S. vessel to regard its guns as pointed at it. The U.S. Navy—whose officers believe the PLAN should have broadcast its plans clearly in advance per customary practice—contacted its attaché in Beijing, and a message went up the PLA chain of command, leading Party leadership to ask the PLAN what it was doing. Finally, the PLAN official saw room for logistics cooperation given the fact that the United States has bases in region, unlike China.

Provided that this were not wielded to attempt to strengthen China’s Near Seas claims, or restrict legal presence, surveillance and exercises in China’s exclusive economic zone and the airspace above it, it might indeed offer some constructive approaches. From a more practical standpoint, as the Gulf of Aden has shown, multilateral cooperation of scale can drastically lower individual providers’ costs.

•

Putting Down Roots Overseas

Will Beijing eventually pursue overseas military basing arrangements to facilitate a more permanent Far Seas presence after the PLAN’s exit from the Gulf of Aden? If so, when and how? Similar to the above discussion of gradual adjustments to Beijing’s longstanding reluctance towards projecting security abroad and when its actions will impact events in other states, China’s uneasiness about overseas basing is also deeply rooted in its own national history. Any change to Beijing’s military basing policy would carry rich symbolic meaning.

Logistics and intelligence support remain key constraints on Chinese operations in the Indian Ocean and beyond. To remedy this, the Pentagon assesses, Beijing “will likely establish several access points in this area in the next 10 years. These arrangements likely will take the form of agreements for refueling, replenishment, crew rest and low-level maintenance. The services provided likely will fall short of permitting the full spectrum of support from repair to rearmament.”250

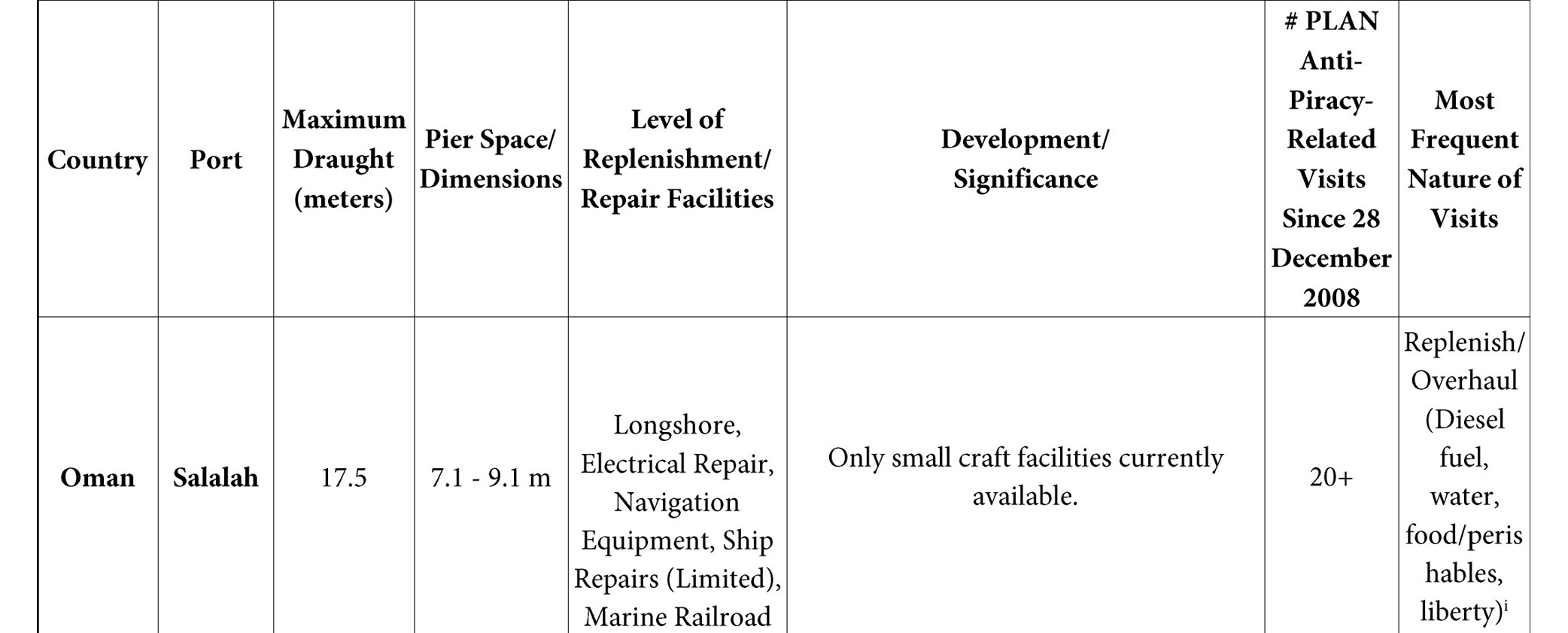

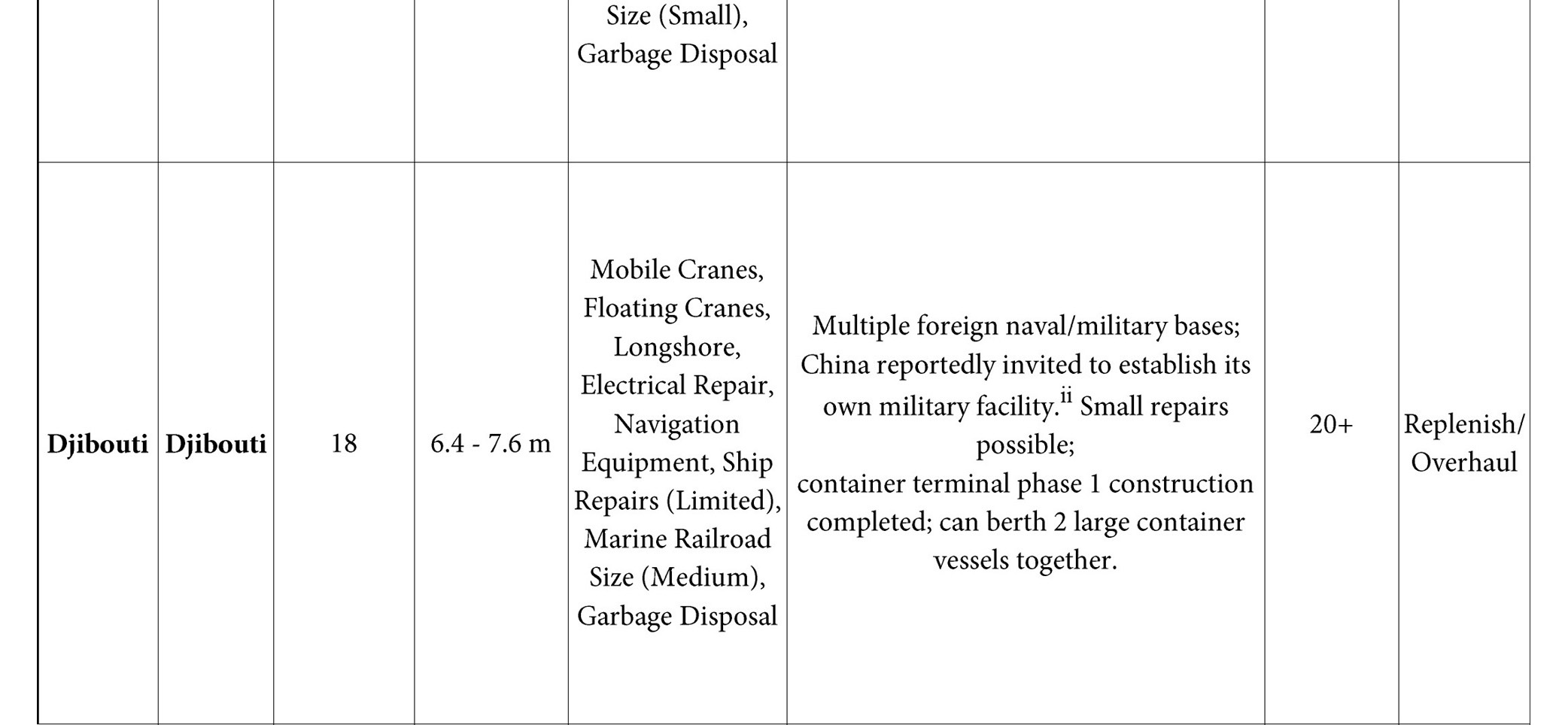

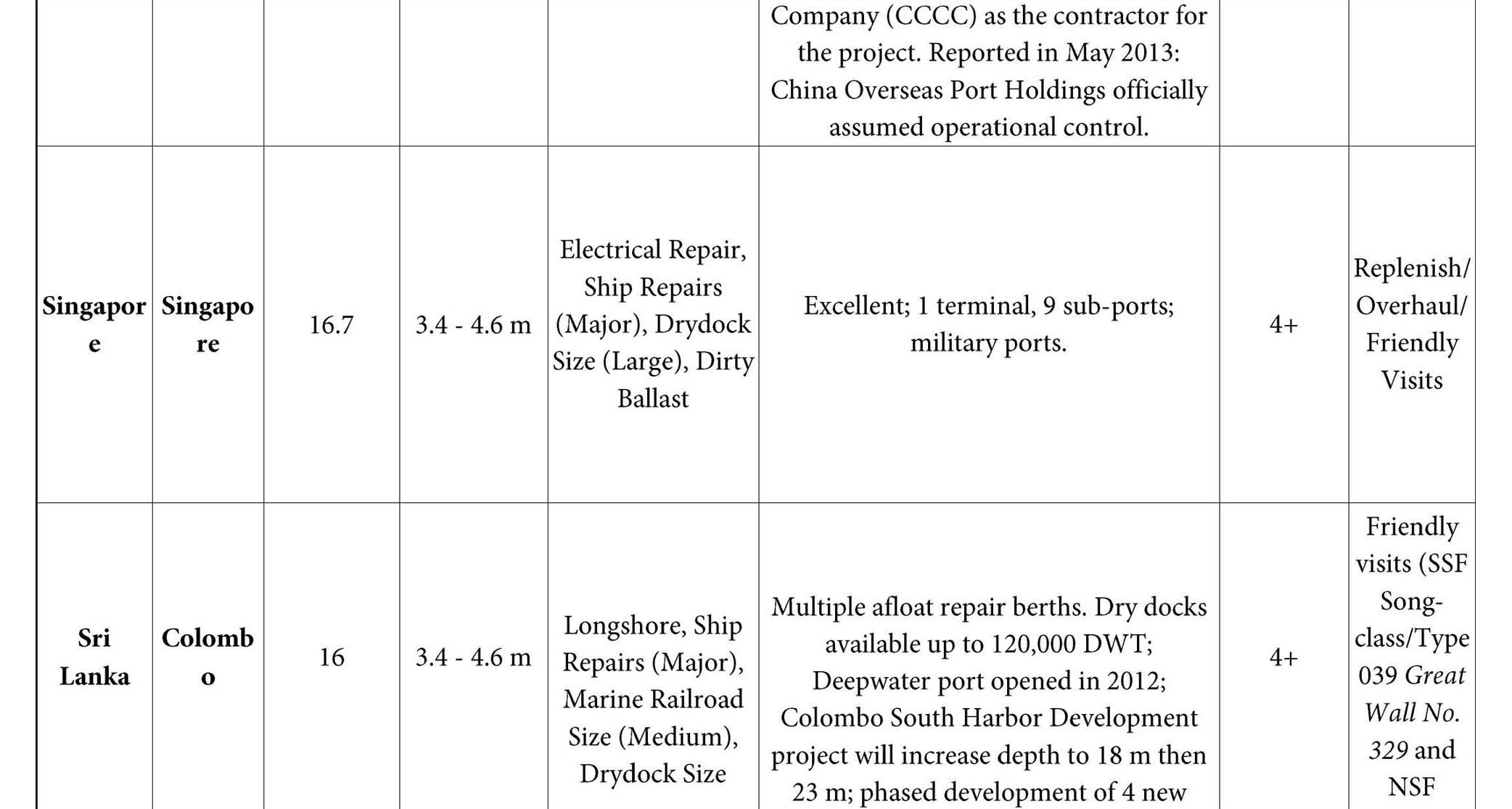

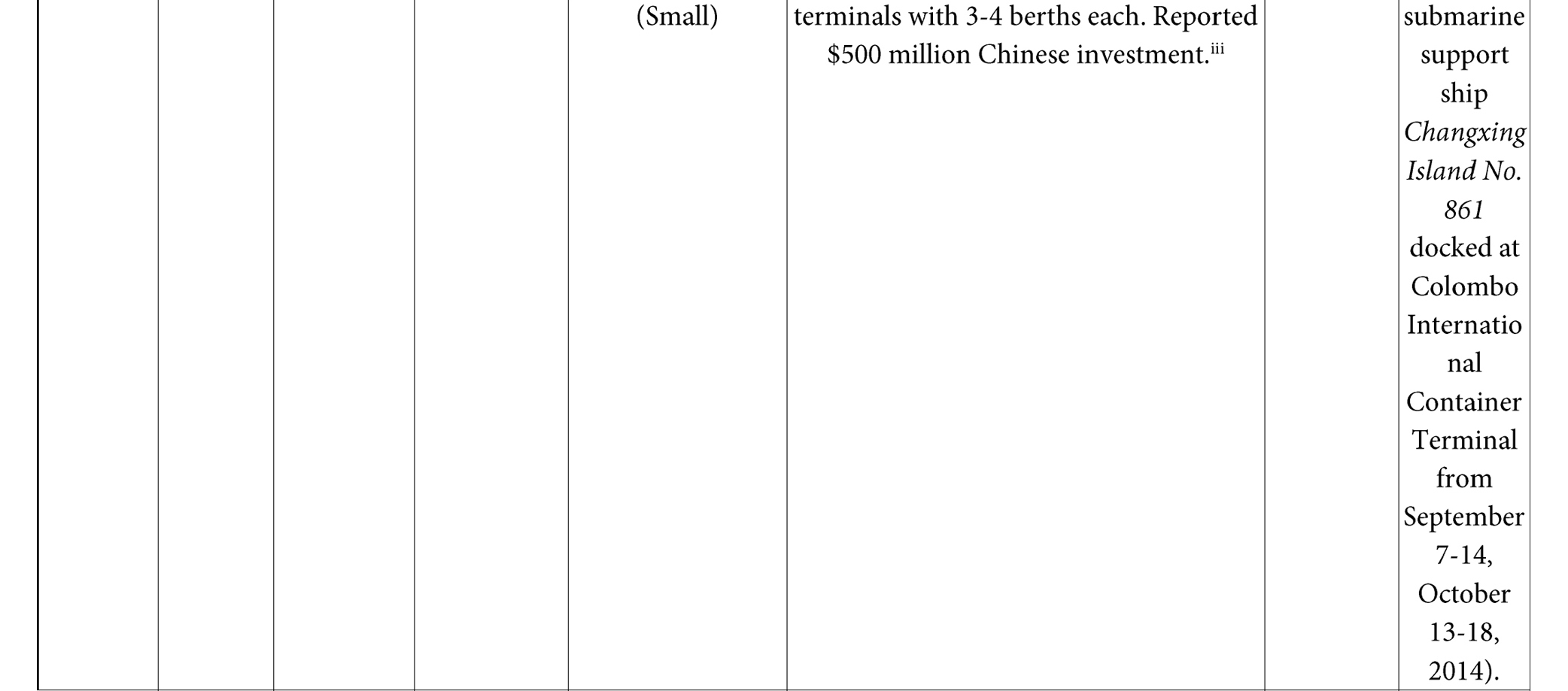

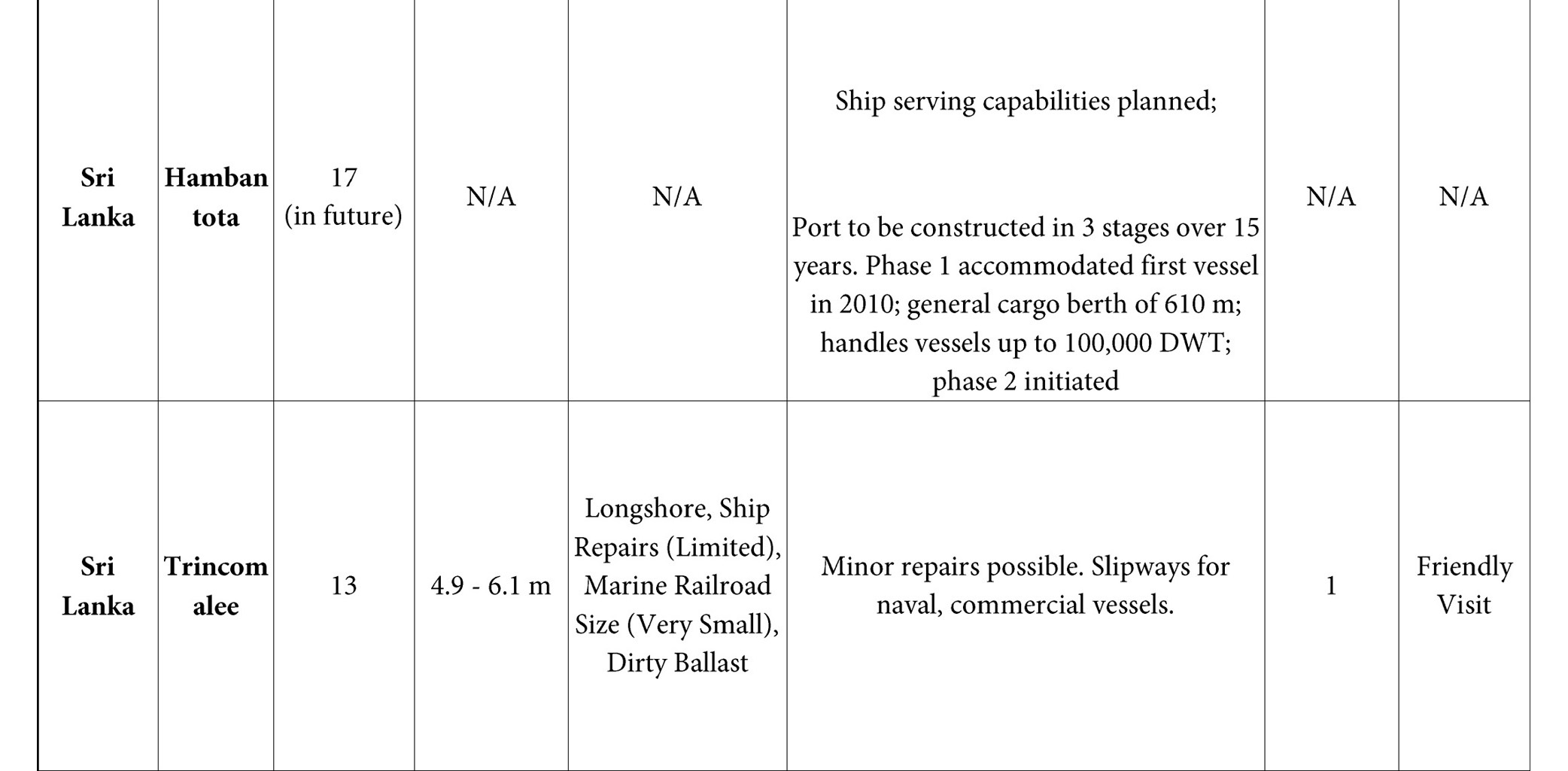

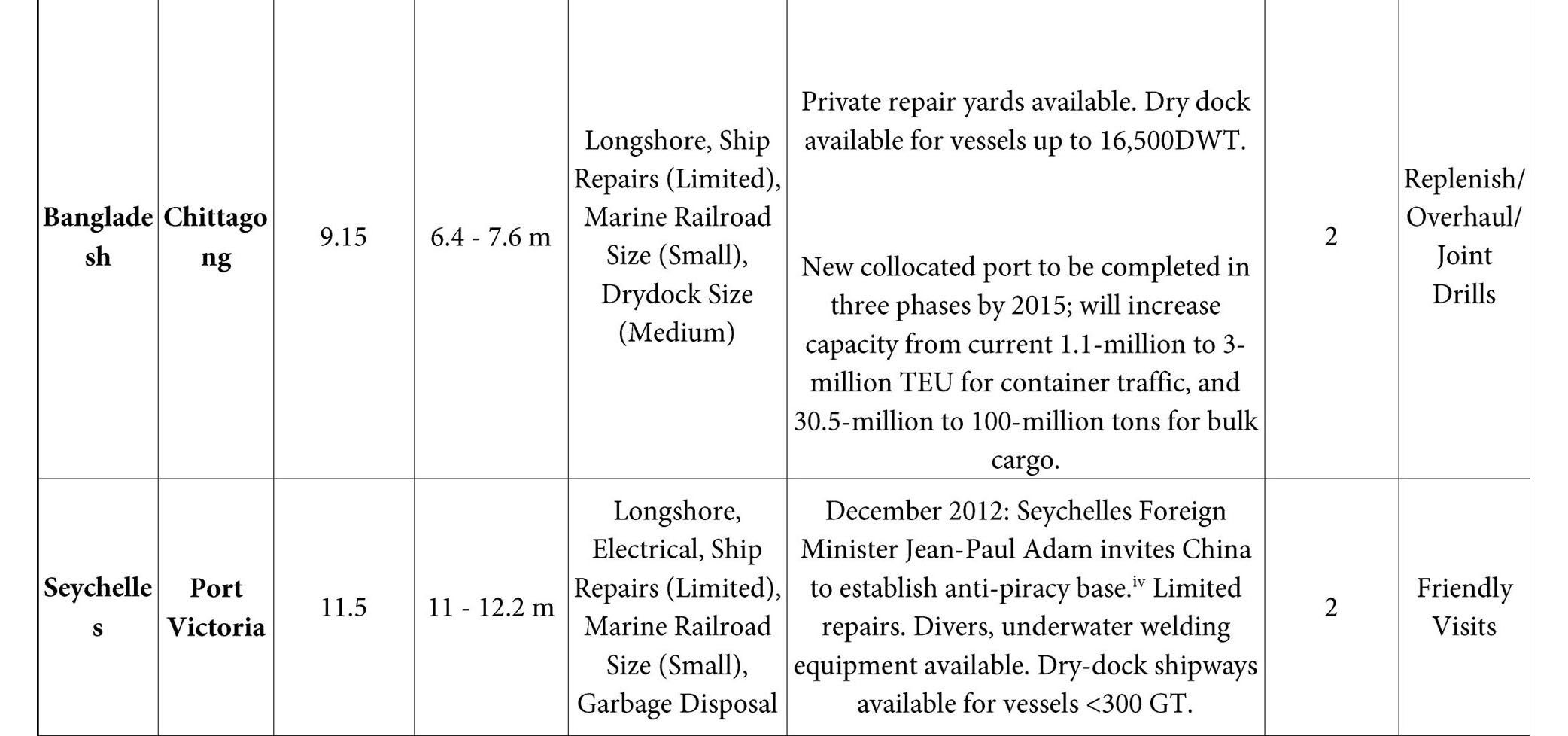

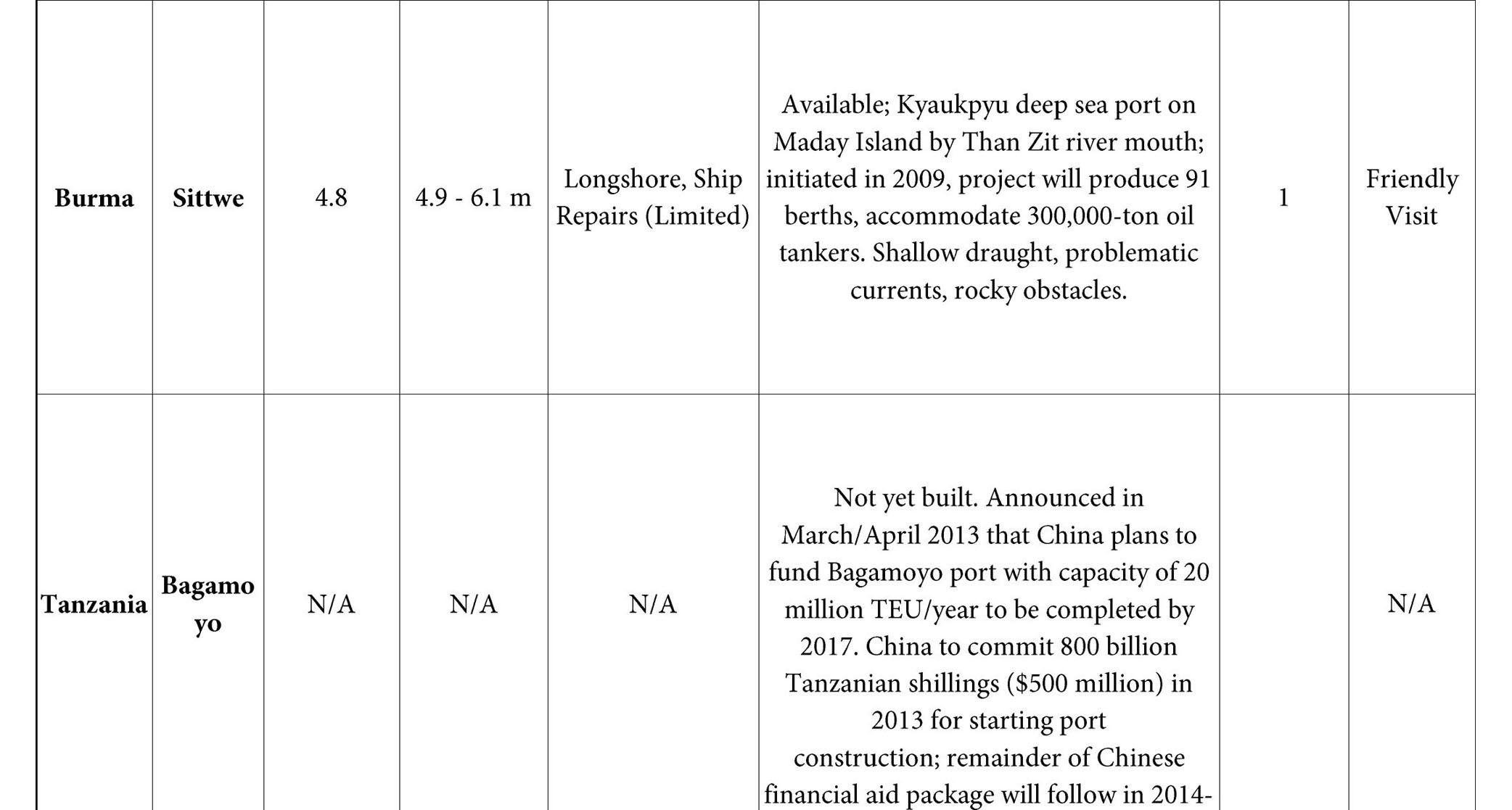

In Exhibit 4 below, several ports in Africa, Asia and the Middle East where China has been involved economically are compared in terms of their nature, capacity, strategic relevance and China’s known involvement therein.

EXHIBIT 4: Ports for Potential PLAN Overseas Access and PLAN Visits Thereto

Note: Plus signs indicate the possibility that not all port calls have been included. For more information on possible PLAN overseas access points, see Andrew S. Erickson and Austin M. Strange, No Substitute for Experience: China’s Anti-Piracy Operations in the Gulf of Aden, Naval War College Press China Maritime Study 10 (November 2013); Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Modernization of Its Naval and Air Power Capabilities,” in Ashley J. Tellis and Travis Tanner, eds., Strategic Asia 2012-13: China’s Military Challenge (Seattle, WA: National Bureau of Asian Research, 2012), pp. 89-91; Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici with Scott Devary and Jenny Lin, “Not an idea We Have to Shun”: Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements in the 21st Century, Institute for National Security Studies China Strategic Perspective 7 (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, October 2014), http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-7.pdf.

i. Christopher D. Yung and Ross Rustici with Scott Devary and Jenny Lin, “Not an idea We Have to Shun”: Chinese Overseas Basing Requirements in the 21st Century, Institute for National Security Studies China Strategic Perspective 7 (Washington, DC: National Defense University Press, October 2014),

http://ndupress.ndu.edu/Portals/68/Documents/stratperspective/china/ChinaPerspectives-7.pdf.

ii. “China Declines to Confirm or Deny Djibouti Base Plan,” Reuters, May 11, 2015, http://af.reuters.com/article/topNews/idAFKBN0NW0XA20150511; “

![]() ” [Djibouti Welcomes China to Build a Base],

” [Djibouti Welcomes China to Build a Base],

![]() [Global Times], March 8, 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/2013-03/08/c_124434216.htm.

[Global Times], March 8, 2013, http://news.xinhuanet.com/2013-03/08/c_124434216.htm.

iii. Cdr. Gurpreet Khurana, Cdr. Kapil Narula and Asha Devi, “PLA Navy Submarine Visits Sir Lanka,” Making Waves, Vol. 19, No. 9.2 (New Delhi: National Maritime Foundation, September 30, 2014), http://maritimeindia.org/pdf/MW%209.2(Final).pdf, 37.

iv. Li Xiaokun and Li Lianxing, “PLA Navy Looks at Offer from Seychelles,” China Daily, December 13, 2011, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2011-12/13/content_14254395.htm; Jeremy Page and Tim Wright, “Chinese Military Considers New Indian Ocean Presence,” Wall Street Journal, December 14, 2011, http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB10001424052970203518404577096261061550538; “Seychelles Invites China to Set Up Anti-Piracy Base,” Defense News, December 2, 2011, http://www.defensenews.com/article/20111202/DEFSECT03/112020302/Seychelles-Invites-China-Set-Up-Anti-Piracy-Base.

Exhibit 4 Sources:

Data obtained from IHS Maritime Sea-web and the following port websites:

http://www.salalahport.com/index.php?lang=en>name=List%20of%20Assets>itemid=162, http://ports.com/oman/port-of-salalah-mina-raysut/; http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/portCall/DJI_Port_of_Djibouti_2169.php,

http://ports.com/djibouti/port-of-djibouti/, http://www.searates.com/port/djibouti_dj.htm;

http://ports.com/pakistan/port-of-karachi/; http://www.gwadarport.gov.pk/portprofile.html;

http://www.searates.com/port/singapore_sg.htm;

http://www.searates.com/port/chittagong_bd.htm;

http://www.searates.com/port/port_victoria_sc.htm;

http://www.worldportsource.com/ports/portCall/MMR_Port_of_Sittwe_2337.php.

As the exhibit shows, PLAN vessels have stopped principally at ports in countries abutting the Gulf of Aden. Its current facilities approach has drawbacks; many Chinese strategists continue to debate access alternatives. Yin Zhuo stated that Gulf of Aden operations have demonstrated that some of the PLAN’s equipment and resources are inadequate for fulfilling blue water missions. In particular, Yin emphasized that information and communications infrastructure was relatively ineffective for conducting Far Seas operations for extended periods, lagging far behind the relevant naval capabilities of Western states.251 Yin has also previously argued for basing arrangements, given that current reliance on supply from Muslim countries is insufficient to provide pork for PLAN task forces with over 800 sailors.252 Pan Chunming, deputy director of an SSF political division, perceives Chinese overseas supply infrastructure as inadequate. Likely referring to Djibouti, he asserts, “Once we coordinated with a foreign port to berth for three days. However, the port later only allowed us to stay for one day, because a Japanese ship was coming.”253 This news could hardly have been well-received by the PLAN. Japan has employed P-3C surveillance aircraft to complement Maritime Self Defense Forces (MSDF) destroyers sent to the Gulf of Aden to conduct anti-piracy operations.254 It dispatches P-3 surveillance flights out of its naval base completed in 2011 and located north of the Djibouti-Ambouli International Airport. Japan announced in August 2013 that it planned to arm Djibouti with additional maritime patrol ships to improve the African state’s littoral security.255 A PLAN official advanced a cynical interpretation of Tokyo’s contribution, stating that Djibouti is not overly concerned with adherence to international standards in its exclusive economic zone (EEZ), and it is rather great powers that typically opposed foreign behavior they perceived as unacceptable in their own EEZs.

Meanwhile, scholar Chen Chundi advocates for a PLAN presence across what he terms the “Islamic Crescent of Chinese Transport,” stretching from Southeast Asia through South Asia, Central Asia and the Middle East, to North Africa. Specifically, Chen calls for China to use positive diplomacy in this region to establish mutually beneficial port call agreements.256

Naval scholar Jing Aiming opts instead for a concept of three different levels of “support points” for China’s Navy in the Far Seas. The first level, including foreign ports such as Djibouti, Aden and Salalah, are adequate for refueling and supply needs, and the PLAN could rely on commercial transaction in these areas. Second, Seychellois Port Victoria could support fixed schedules of PLAN ship supply, air-based reconnaissance and platform replenishment. Third, ports in places like Pakistan could support long-term, bilateral contractual agreements that enable more comprehensive supply, replenishment and large-scale weaponry repair.257

Despite local resource limitations, the Seychelles has emerged in recent years with Djibouti and Karachi, Pakistan as a frontrunner for a potential Chinese military base or regular access point. In March 2012 China announced plans to establish a presence in the Seychelles to support its anti-piracy mission.258 That said, China’s official response was wary of comparing such a presence to a military base, and insisted that it would be used purely for logistical and supply purposes. China’s Ministry of Defense explained, “According to escort needs and the needs of other long-range missions, China will consider seeking supply facilities at appropriate harbors in the Seychelles or other countries.”259 In May 2012, both nations signed an agreement allowing the PLAN to transfer detained pirates to Seychelles.260 In July 2013 they signed an agreement to enhance coordination between each side’s foreign ministries, while also discussing a number of bilateral projects ranging from marine research and security to direct flights between China and Seychelles.261 Similarly, in March 2013 Djibouti, where PLAN forces have docked over fifty times as of 2012, invited China to build a military presence there.262 In 2014, China and Djibouti reportedly signed a security and defence strategic partnership agreement that facilitates PLAN access.263 In mid-2015 Djibouti President Ismail Omar Guelleh purportedly claimed that negotiations with Beijing on a Chinese military base in Djibouti were ongoing.264 A Chinese foreign ministry spokesperson initially neither confirmed nor denied the report.

China may thus establish its first batch of limited overseas strategic support points in the IOR in order to support a regularized PLAN presence. In Jing Aiming’s vision, strategic support points can be divided as follows. First-level points serve primarily to fuel and replenish PLAN ships in peacetime, and could include the ports of Djibouti and Salalah, both of which PLAN anti-piracy escort ships have called on extensively in recent years. Second-level points help with relatively fixed ship and aircraft berthing and replenishment as well as sailor rest. The Seychelles’ Victoria Port could be an ideal second-tier point. Third-level access points are more comprehensive, offering all-inclusive replenishment, and supporting rest, reorganization and major ship repairs. Pakistan could potentially provide such a base. Jing thinks that within a decade it is possible to achieve this nodal system that involves northern and western Indian Ocean replenishment lines incorporating ports in the Middle East as well as northern and eastern Africa. Meanwhile, central and southern lines could rely on the Seychelles and Madagascar.265

China and other states may also be increasingly willing to adopt more proactive approaches to maritime piracy and other nontraditional security threats to the global commons, possibly including entering the sovereign territory of other nations under special circumstances. In 2011 Chief of PLA General Staff Chen Bingde stated, “For counter-piracy campaigns to be effective, we should probably move beyond the ocean and crush their bases on the land.” Chen elaborated, “we should not only fight with pirates on the sea, but also on the ground; because those pirates operating on the sea are simply low-ranking ones, and the true masterminds are on the ground. All the ransoms and treasures they obtained were all later handed over to their chiefs of organizations.”266 Chen’s words reflect widely held beliefs among both Chinese and non-Chinese leaders that eradicating piracy and similar nontraditional security threats ultimately requires more “bottom-up,” holistic approaches.

•

Although China’s regional objectives have not changed, its strategic environment has. More importantly, China’s strategic means have increased and strengthened. Achieving a stable surrounding environment has constantly been a central strategic objective of Chinese diplomacy. While refuting the “Chinese threat doctrine” in the late 1990s, an important piece of evidence used by Chinese leaders was the fact that China’s military—lacking even a single aircraft carrier—was defensive in nature and did not constitute a threat to neighboring countries. Clearly, Chinese military force has made great strides in recent years. In December 2008, a Chinese naval escort formation entered the Gulf of Aden in the Indian Ocean for the first time, and China announced that it was going to build an indigenous Chinese aircraft carrier.

Now an increasingly capable Chinese Navy is increasingly visible to the world, incentivizing its civilian masters to balance Near Seas assertiveness with Far Seas public goods contributions. Discussion of potential avenues for future Far Seas military access for China thus raises important questions about what types of missions the PLAN may pursue outside of the Second Island Chain in the post-Gulf of Aden anti-piracy era.

•

![]()

194 Peng Yining, “Navy Lauded for Foiling Pirates,” China Daily, December 26, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8495596.html.

195

![]() [Li Ruijing], “

[Li Ruijing], “

![]() ” [Borrowing from Escorts to Expand Blue-Water Navy], World Journal, April 11, 2012, www.ahwang.cn/sjb/html/2012-04/1l/content_l51231.htm?div=-1

” [Borrowing from Escorts to Expand Blue-Water Navy], World Journal, April 11, 2012, www.ahwang.cn/sjb/html/2012-04/1l/content_l51231.htm?div=-1

196 Ben Marino, “China’s Public Sector Looks to Private Security for Help,” Financial Times, November 26, 2013, http://www.ft.eom/cms/s/0/626a2ac8-5272-1le3-8586-00144feabdc0.html#axzz2tC2ZoSTN.

197 Mathieu Duchâtel, Oliver Brâuner and Zhou Hang, Protecting China’s Overseas Interests: The Slow Shift away from Non-interference, SIPRI Policy Paper, No. 41 (June 2014), http://books.sipri.org/product_info?c_product_id=479, p. 51.

198 Ibid., pp. 54-55.

199 Bree Feng, “Chinese Bodyguards, When Police Won’t Do,” Sinosphere, New York Times, October 14, 2013, http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/10/14/chinese-bodyguards-when-police-wont-do/?_php=true&_type=blogs&_r=0.

200 Mathieu Duchâtel, Oliver Brâuner and Zhou Hang, Protecting China’s Overseas Interests: The Slow Shift away from Non-interference, SIPRI Policy Paper, No. 41 (June 2014), http://books.sipri.org/product_info?c_product_id=479, pp. 54-55.

201 David Feith, “Erik Prince: Out of Blackwater and Into China,” Wall Street Journal, January 24, 2014, http://online.wsj.eom/news/artides/SB10001424052702303465004579324650302912522.

202 “Changzhou Warship of PLA Navy’s Twelfth Escort Formation Successfully Receives 26 Crew Members of Taiwan’s ‘Hsu Fu-1’ Fishing Vessel,” Military Report, CCTV-7 (Mandarin), 1130 GMT, September 18, 2012.

203 “‘Peace Ark’ Hospital Ship Leaves Gulf of Aden,” Liberation Army Daily, July 29, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90786/8345729.html.

204

![]() [Liu Wenping and Ju Zhenhua] “

[Liu Wenping and Ju Zhenhua] “

![]() ” [New Course of “Harmonious Ocean”—Overview of Task Harmonious Mission-2013], People’s Navy, October 16, 2013, p. 2A.

” [New Course of “Harmonious Ocean”—Overview of Task Harmonious Mission-2013], People’s Navy, October 16, 2013, p. 2A.

205 “China Frigate Completes Second Escort of Syrian Chemical Weapons,” China Military Online, January 29, 2014, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/TopNews/2014-01/29/content_4487936.htm.

206 “China to Continue Syrian Shipment Support: FM,” Xinhua, February 11, 2014, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/china/2014-02/1l/c_133107071.htm.

207 Michael D. Swaine, “Chinese Views and Commentary on the East China Sea Air Defense Identification Zone (ECS ADIZ),” China Leadership Monitor, No. 43 (2014), http://carnegieendowment.org/files/CLM43MSCarnegie013114.pdf.

208 Zheng Kaijun, “China’s Commitment to Escorting Syrian Chemical Weapons Transportation Significant,” Xinhua, December 19, 2013, http://english.peopledaily.com.cn/90883/8489201.html.

209 “Chinese Warship Fulfills Third Mission of Escorting Syria’s Chemical Weapons Shipping,” China Military Online, February 12, 2014, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/2014-02/12/content_5767470.htm.

210 “China’s Image Enhanced in Escort Mission of Shipping Syrian’s Chemical Weapons,” Liberation Army Daily, December 20, 2013, http://eng.chinamil.com.cn/news-channels/china-military-news/2013-12/20/content_5700371.htm.

211 “China and Russia to Hold Joint Drill in the Mediterranean Sea,” CNTV, January 21, 2014, http://english.cntv.cn/program/china24/20140121/100459.shtml.

212 Nathan Beauchamp-Mustafaga, “PLA Navy Used for the First Time in Naval Evacuation from Yemen Conflict,” Jamestown China Brief, Vol. 15, No. 7 (April 3, 2015), http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=43751&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=789&no_cache=l#.VVTsX_lVhBc.

213 “Last Chinese Citizens Evacuated from Yemen,” Xinhua, April 7, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/video/2015-04/07/c_l34130134.htm.

214 “Chinese Navy Helps Hundreds of Foreign Nationals Evacuate War-Torn Yemen,” South China Morning Post, April 3,2015, http://www.scmp.com/news/china/article/1755221/china-evacuates-foreigners-war-torn-yemen.

215 Austin M. Strange and Andrew S. Erickson, “China’s Global Maritime Presence: Hard and Soft Dimensions of PLAN Antipiracy Operations,” Jamestown China Brief" Vol. 15, No. 9 (May 1, 2015), http://www.jamestown.org/programs/chinabrief/single/?tx_ttnews%5Btt_news%5D=43868&tx_ttnews%5BbackPid%5D=25&cHash=8a087cfl51074eed214dfe5bba01edbf#.VVJPDflVhHw.

216 “China, Russia Launch Joint Naval Drills,” Xinhua, May 11, 2015, http://news.xinhuanet.com/english/2015-05/11/c_134229911.htm.

217 The PLA Navy: New Capabilities and Missions for the 21st Century (Suitland, MD: Office of Naval Intelligence, 2015), p. 43.

218 Greg Torode, “No Sign of Help for Philippines from China’s Hospital Ship,” Reuters, November 15, 2013, http://www.reuters.com/article/2013/11/15/us-philippines-typhoon-china-idUSBRE9AE0BA20131115.

219 “Remarks by USAID Asia Bureau Deputy Assistant Administrator Greg Beck for ‘The Response to Philippines’ Typhoon Haiyan’ Conference,” Center for Strategic & International Studies (CSIS), Washington, DC, January 8, 2014, http://www.usaid.gov/news-information/speeches/jan-08-2014-remarks-daa-greg-beck-response-philippines-typhoon-haiyan.

220 Zhong Kuirun, “The Responsibility and Undertaking of the Chinese Navy: Three Revelations of the Sixth Escort Task Force’s Escorts in the Gulf of Aden,” Liberation Army Daily, November 30, 2010.

221 David E. Brown, Africa’s Booming Oil and Natural Gas Exploration and Production: National Security Implications for the United States and China (Carlisle, PA: Army War College Press, December 2013), pp. 85-86.

222 Shannon Tiezzi, “Chinese Navy’s Role in Syrian Chemical Weapons Disposal,” The Diplomat, December 20, 2013, http://thediplomat.com/2013/12/chinese-navys-role-in-syrian-chemical-weapons-disposal/.

223 Mark J. Valencia and Nazery Khalid, “The Somalia Multilateral Anti-Piracy Approach: Caveats on Vigilantism,” The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus, Vol. 8, No. 4, February 17, 2009, http://www.japanfocus.org/-Mark_J_-Valencia/3052.

224 Admiral Wu Shengli, discussion with one of the authors.

225 Piracy and Armed Robbery Against Ships, ICC International Maritime Bureau (IMB) report for the period January 1-December 31, 2013, published in January 2014, p. 5.

226 Admiral Wu Shengli, discussion with one of the authors.

227 Chen Bingde, “Speech Delivered at the U.S. National Defense University,” Washington, D.C., May 18, 2011.

228 Anna Culaba, “Somali Pirates Hijacked Zero Boats This Year,” RYOT News, December 27, 2013, http://www.ryot.org/somali-pirates-hijacked-zero-boats-year/513057?goback=.gde_1191857_member_5823841618339332099#.

229 A recent study on the Gulf of Aden mission states: “Presently, it is still not very safe in the Gulf of Aden and Somalia Waters. It is an arduous task and the convoy officers and men of the Chinese Navy still have a long way to go.” Gao Xiaoxing et al., The PLA Navy (Beijing: China Intercontinental Press, 2012), p. 155.

230 Li Jie, “A New Milestone in Going to the Ocean,” Five Year Escort Special Column, Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2013), pp. 21-22.

231 “Japan to Send SDF Officer to Take Command of Int’l Anti-piracy Force,” Kyodo News International, July 18, 2014, http://www.globalpost.com/dispatch/news/kyodo-news-international/140718/japan-send-sdf-officer-take-command-intl-anti-piracy-fo.

232 “MSDF Officer to Take Key Post at Pentagon,” Japan Times, July 9, 2014, http://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2014/07/09/national/politics-diplomacy/msdf-officer-to-take-up-post-at-key-pentagon-naval-unit/#.U9gAZlZN3wI.

233 Anti-piracy operations have essentially been continuous since their inception, save for extenuating circumstances such as the aforementioned temporary cessation of operations to evacuate Chinese and foreign citizens from war-torn Yemen.

234 Li Jie, “A New Milestone in Going to the Ocean,” Five Year Escort Special Column, Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2013), p. 24.

235 Ibid., p. 22.

236 “Conversation with Yin Zhuo: Escorts Are an Epoch-Making Event,” Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2011), p. 22

237 “China’s Navy Starts West Pacific Drill,” Xinhua, February 3, 2014, http://www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/China-Military-Watch/2014-02/03/content_17267984.htm.

238 Jane Perlez, “Chinese Navy to Aid U.S. Ship Destroying Syrian Chemical Weapons,” New York Times, December 20, 2013, http://sinosphere.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/12/20/chinese-navy-to-aid-u-s-ship-destroying-syrian-chemical-weapons/?_r=0.

239 Andrew S. Erickson and Austin M. Strange, “A Role for China in Gulf of Guinea Security?” The National Interest, December 10, 2013, http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/piracy%E2%80%99s-next-frontier-role-china-gulf-guinea-security-9533?page=4.

240 David E. Brown, Hidden Dragon, Crouching Lion: How China’s Advance in Africa is Underestimated and Africa’s Potential Underappreciated, U.S. Army War College Strategic Studies Institute Monograph, September 2012, pp. 96- 99, http://www.strategicstudiesinstitute.army.mil/pdffiles/PUB1120.pdf.

241 “EU to Boost Anti-Piracy Efforts in W. Africa,” Agence France Presse, August 28, 2013, http://www.google.com/hostednews/afp/article/ALeqM5jiydJzcKVEbWWniErGvo3ypthZhA?docId=CNG.afdaeeclfc7c25e9ddfelfcbfd8d7b67.1al.

242 Admiral Wu Shengli, discussion with one of the authors.

243 Mrityunjoy Mazumdar, “Nigerian Navy Commissions Four Vessels,” IHS Jane’s 360, February 19, 2015, http://www.janes.com/article/49162/nigerian-navy-commissions-four-vessels.

244 Sr. Col. Zhou Bo, “Security of SLOCs and International Cooperation,” presentation at “ASEAN Regional Forum Seminar on SLOC Security,” Beijing, December 8, 2014.

245

![]() 19

19

![]() [Syrian Chemical Weapons Destruction Operation Begins December 19 Chinese Navy Will Visit Mediterranean Sea for Escorts],

[Syrian Chemical Weapons Destruction Operation Begins December 19 Chinese Navy Will Visit Mediterranean Sea for Escorts],

![]() [Qianjiang Evening News], December 20, 2013, http://china.haiwainet.cn/n/2013/1220/c345646-20061957.html.

[Qianjiang Evening News], December 20, 2013, http://china.haiwainet.cn/n/2013/1220/c345646-20061957.html.

246 “Chinese Naval Taskforce Shifts to Maritime Exercise Phase of RIMPAC,” Liberation Army Daily, July 11, 2014, http://eng.mod.gov.cn/DefenseNews/2014-07/11/content_4521731.htm; Ding Ying, “Taking Part at Sea,” Beijing Review, July 5, 2014, http://www.bjreview.com.cn/quotes/txt/2014-08/14/content_627873.htm; “Focus Today,” CCTV-4 (Mandarin), 1330-1400 GMT, July 3, 2014.

247 Unless otherwise specified, the insights in this paragraph are from the minutes of the twenty-fourth and twenty-fifth SHADE meetings.

248 S. Korea Send Anti-Piracy Troops to Gulf of Aden,” Yonhap, January 16, 2014, http://english.yonhapnews.co.kr/news/2014/01/16/0200000000AEN20140116007200315.html.

249 Channel 16 VHF is a marine radio frequency commonly used for initial calling of ships, including in situations of distress.

250 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2015, Annual Report to Congress (Arlington, VA: Office of the Secretary of Defense, May 8, 2015), p. 41.

251 Military and Security Developments Involving the People’s Republic of China 2011 (Arlington, VA: Office of the Secretary of Defense, May 6, 2011), p. 62.

252 “Conversation with Yin Zhuo: Escorts Are an Epoch-Making Event,” Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2011), p. 22.

253 Yang Jingjie, “Captains Courageous,” Global Times, December 24, 2012, http://www.globaltimes.cn/content/751957.shtml.

254 “Deepen Ties with Nations of GCC to Ensure Energy Security,” Editorial. Yomiuri Shimbun Online, August 25, 2013, http://www.yomiuri.co.jp.

255 “Japan to Provide Patrol Ships to Djibouti to Enhance Maritime Security,” Kyodo World Service, August 27, 2013.

256 “

![]() ” [How Does China Protect Its Overseas Interests?],

” [How Does China Protect Its Overseas Interests?],

![]() [Modern Ships] (April 2011), pp. 14-17.

[Modern Ships] (April 2011), pp. 14-17.

257

![]() [Jing Aiming], “

[Jing Aiming], “

![]() ” [China’s Overseas Military Basing Proceeding Gradually],

” [China’s Overseas Military Basing Proceeding Gradually],

![]() [Sunset], No. 2 (February 2012), p. 25.

[Sunset], No. 2 (February 2012), p. 25.

258 Ng Tze-Wei, “Beijing Will Consider Seychelles Basing Offer,” South China Morning Post, December 13, 2011, http://www.scmp.com/article/987633/beijing-will-consider-seychelles-base-offer.

259 Li Xiaokun and Li Lianxing, “Navy Looks at Offer from Seychelles,” China Daily, December 13, 2011, www.chinadaily.com.cn/china/2011-12/13/content_14254395.htm.

260 “Seychelles and China Sign Accord on Transfer of Suspected Pirates,” Seychelles Nation, May 19, 2012, article.wn.com/view/2012/05/19/Seychelles_and_China_sign_accord_on_transfer_of_suspected_pi/.

261 “China and Seychelles Create Stimulus for Further Consultation,” Seychelles Nation, July 25, 2013, http://www.nation.sc/article.html?id=239346.

262 “Conversation with Yin Zhuo: Escorts Are an Epoch-Making Event,” Navy Today, No. 12 (December 2011), p. 22.

263 John Lee, China Comes to Djibouti,” Foreign Affairs, April 23, 2015, https://www.foreignaffairs.com/articles/east-africa/2015-04-23/china-comes-djibouti; “Djibouti and China Sign a Security and Defense Agreement,” February 27, 2014, http://allafrica.com/stories/201402280055.html.

264 “China ‘Negotiates Military Base’ in Djibouti,” Al Jazeera, May 9, 2015, http://www.aljazeera.com/news/africa/2015/05/150509084913175.html.

265

![]() [Jing Aiming], “

[Jing Aiming], “

![]() ” [China’s Overseas Military Basing Proceeding Gradually], Sunset, No. 2 (February 2012), p. 25.

” [China’s Overseas Military Basing Proceeding Gradually], Sunset, No. 2 (February 2012), p. 25.

266 Chen Bingde, “Speech Presented at the U.S. National Defense University,” Washington, D.C., May 18, 2011.