In science fiction, space and time warps are commonplace. They are used for rapid journeys around the galaxy or for travel through time. But today’s science fiction is often tomorrow’s science fact. So what are the chances of time travel?

The idea that space and time can be curved or warped is fairly recent. For more than 2,000 years the axioms of Euclidean geometry were considered to be self-evident. As those of you who were forced to learn geometry at school may remember, one of the consequences of these axioms is that the angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees.

However, in the last century people began to realise that other forms of geometry were possible in which the angles of a triangle need not add up to 180 degrees. Consider, for example, the surface of the Earth. The nearest thing to a straight line on the surface of the Earth is what is called a great circle. These are the shortest paths between two points so they are the routes that airlines use. Consider now the triangle on the surface of the Earth made up of the equator, the line of 0 degrees longitude through London and the line of 90 degrees longtitude east through Bangladesh. The two lines of longitude meet the equator at a right angle, or 90 degrees. The two lines of longitude also meet each other at the North Pole at a right angle, or 90 degrees. Thus one has a triangle with three right angles. The angles of this triangle add up to 270 degrees which is obviously greater than the 180 degrees for a triangle on a flat surface. If one drew a triangle on a saddle-shaped surface one would find that the angles added up to less than 180 degrees.

The surface of the Earth is what is called a two-dimensional space. That is, you can move on the surface of the Earth in two directions at right angles to each other: you can move north–south or east–west. But of course there is a third direction at right angles to these two and that is up or down. In other words the surface of the Earth exists in three-dimensional space. The three-dimensional space is flat. That is to say it obeys Euclidean geometry. The angles of a triangle add up to 180 degrees. However, one could imagine a race of two-dimensional creatures who could move about on the surface of the Earth but who couldn’t experience the third direction of up or down. They wouldn’t know about the flat three-dimensional space in which the surface of the Earth lives. For them space would be curved and geometry would be non-Euclidean.

But just as one can think of two-dimensional beings living on the surface of the Earth, so one could imagine that the three-dimensional space in which we live was the surface of a sphere in another dimension that we don’t see. If the sphere were very large, space would be nearly flat and Euclidean geometry would be a very good approximation over small distances. But we would notice that Euclidean geometry broke down over large distances. As an illustration of this imagine a team of painters adding paint to the surface of a large ball.

As the thickness of the paint layer increased, the surface area would go up. If the ball were in a flat three-dimensional space one could go on adding paint indefinitely and the ball would get bigger and bigger. However, if the three-dimensional space were really the surface of a sphere in another dimension its volume would be large but finite. As one added more layers of paint the ball would eventually fill half the space. After that the painters would find that they were trapped in a region of ever-decreasing size, and almost the whole of space would be occupied by the ball and its layers of paint. So they would know that they were living in a curved space and not a flat one.

This example shows that one cannot deduce the geometry of the world from first principles as the ancient Greeks thought. Instead one has to measure the space we live in and find out its geometry by experiment. However, although a way to describe curved spaces was developed by the German Bernhard Riemann in 1854, it remained just a piece of mathematics for sixty years. It could describe curved spaces that existed in the abstract, but there seemed no reason why the physical space we lived in should be curved. This reason came only in 1915 when Einstein put forward the general theory of relativity.

General relativity was a major intellectual revolution that has transformed the way we think about the universe. It is a theory not only of curved space but of curved or warped time as well. Einstein had realised in 1905 that space and time are intimately connected with each other, which is when his theory of special relativity was born, relating space and time to each other. One can describe the location of an event by four numbers. Three numbers describe the position of the event. They could be miles north and east of Oxford Circus and the height above sea level. On a larger scale they could be galactic latitude and longitude and distance from the centre of the galaxy.

The fourth number is the time of the event. Thus one can think of space and time together as a four-dimensional entity called space–time. Each point of space–time is labelled by four numbers that specify its position in space and in time. Combining space and time into space–time in this way would be rather trivial if one could disentangle them in a unique way. That is to say if there was a unique way of defining the time and position of each event. However, in a remarkable paper written in 1905 when he was a clerk in the Swiss patent office, Einstein showed that the time and position at which one thought an event occurred depended on how one was moving. This meant that time and space were inextricably bound up with each other.

The times that different observers would assign to events would agree if the observers were not moving relative to each other. But they would disagree more the faster their relative speed. So one can ask how fast does one need to go in order that the time for one observer should go backwards relative to the time of another observer. The answer is given in the following limerick:

There was a young lady of Wight

Who travelled much faster than light

She departed one day

In a relative way

And arrived on the previous night.

So all we need for time travel is a spaceship that will go faster than light. Unfortunately in the same paper Einstein showed that the rocket power needed to accelerate a spaceship got greater and greater the nearer it got to the speed of light. So it would take an infinite amount of power to accelerate past the speed of light.

Einstein’s paper of 1905 seemed to rule out time travel into the past. It also indicated that space travel to other stars was going to be a very slow and tedious business. If one couldn’t go faster than light the round trip from us to the nearest star would take at least eight years and to the centre of the galaxy about 50,000 years. If the spaceship went very near the speed of light it might seem to the people on board that the trip to the galactic centre had taken only a few years. But that wouldn’t be much consolation if everyone you had known had died and been forgotten thousands of years ago when you got back. That wouldn’t be much good for science-fiction novels either, so writers had to look for ways to get round this difficulty.

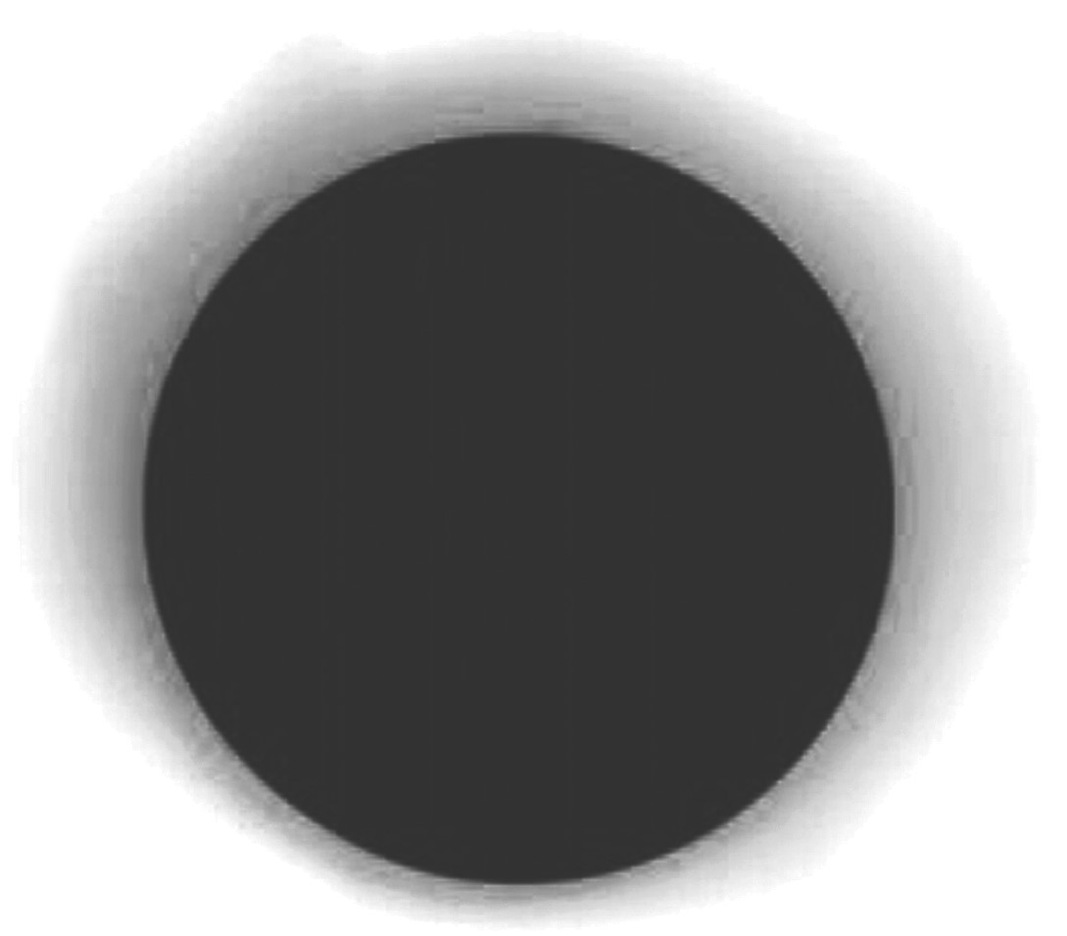

In 1915, Einstein showed that the effects of gravity could be described by supposing that space–time was warped or distorted by the matter and energy in it, and this theory is known as general relativity. We can actually observe this warping of space–time produced by the mass of the Sun in the slight bending of light or radio waves passing close to the Sun.

This causes the apparent position of the star or radio source to shift slightly when the Sun is between the Earth and the source. The shift is very small, about a thousandth of a degree, equivalent to a movement of an inch at a distance of a mile. Nevertheless it can be measured with great accuracy and it agrees with the predictions of general relativity. We have experimental evidence that space and time are warped.

The amount of warping in our neighbourhood is very small because all the gravitational fields in the solar system are weak. However, we know that very strong fields can occur, for example in the Big Bang or in black holes. So can space and time be warped enough to meet the demands from science fiction for things like hyperspace drives, wormholes or time travel? At first sight all these seem possible. For example, in 1948 Kurt Gödel found a solution to Einstein’s field equations of general relativity that represents a universe in which all the matter was rotating. In this universe it would be possible to go off in a spaceship and come back before you had set out. Gödel was at the Institute of Advanced Study in Princeton, where Einstein also spent his last years. He was more famous for proving you couldn’t prove everything that is true even in such an apparently simple subject as arithmetic. But what he proved about general relativity allowing time travel really upset Einstein, who had thought it wouldn’t be possible.

We now know that Gödel’s solution couldn’t represent the universe in which we live because it was not expanding. It also had a fairly large value for a quantity called the cosmological constant which is generally believed to be very small. However, other apparently more reasonable solutions that allow time travel have since been found. A particularly interesting one from an approach known as string theory contains two cosmic strings moving past each other at a speed very near to but slightly less than the speed of light. Cosmic strings are a remarkable idea of theoretical physics which science-fiction writers don’t really seem to have caught on to. As their name suggests they are like string in that they have length but a tiny cross-section. Actually they are more like rubber bands because they are under enormous tension, something like a hundred billion billion billion tonnes. A cosmic string attached to the Sun would accelerate it from nought to sixty in a thirtieth of a second.

Cosmic strings may sound far-fetched and pure science fiction, but there are good scientific reasons to believe they could have formed in the very early universe shortly after the Big Bang. Because they are under such great tension one might have expected them to accelerate to almost the speed of light.

What both the Gödel universe and the fast-moving cosmic-string space–time have in common is that they start out so distorted and curved that space–time curves back on itself and travel into the past was always possible. God might have created such a warped universe, but we have no reason to think that he did. All the evidence is that the universe started out in the Big Bang without the kind of warping needed to allow travel into the past. Since we can’t change the way the universe began, the question of whether time travel is possible is one of whether we can subsequently make space–time so warped that one can go back to the past. I think this is an important subject for research, but one has to be careful not to be labelled a crank. If one made a research grant application to work on time travel it would be dismissed immediately. No government agency could afford to be seen to be spending public money on anything as way out as time travel. Instead one has to use technical terms like closed time-like curves, which are code for time travel. Yet it is a very serious question. Since general relativity can permit time travel, does it allow it in our universe? And if not, why not?

Closely related to time travel is the ability to travel rapidly from one position in space to another. As I said earlier, Einstein showed that it would take an infinite amount of rocket power to accelerate a spaceship to beyond the speed of light. So the only way to get from one side of the galaxy to the other in a reasonable time would seem to be if we could warp space–time so much that we created a little tube or wormhole. This could connect the two sides of the galaxy and act as a short cut to get from one to the other and back while your friends were still alive. Such wormholes have been seriously suggested as being within the capabilities of a future civilisation. But if you can travel from one side of the galaxy to the other in a week or two you could go back through another wormhole and arrive back before you had set out. You could even manage to travel back in time with a single wormhole if its two ends were moving relative to each other.

One can show that to create a wormhole one needs to warp space–time in the opposite way to that in which normal matter warps it. Ordinary matter curves space–time back on itself, like the surface of the Earth. However, to create a wormhole one needs matter that warps space–time in the opposite way, like the surface of a saddle. The same is true of any other way of warping space–time to allow travel to the past if the universe didn’t begin so warped that it allowed time travel. What one would need would be matter with negative mass and negative energy density to make space–time warp in the way required.

Energy is rather like money. If you have a positive bank balance, you can distribute it in various ways. But, according to the classical laws that were believed until quite recently, you weren’t allowed to have an energy overdraft. So these classical laws would have ruled out us being able to warp the universe in the way required to allow time travel. However, the classical laws were overthrown by quantum theory, which is the other great revolution in our picture of the universe apart from general relativity. Quantum theory is more relaxed and allows you to have an overdraft on one or two accounts. If only the banks were as accommodating. In other words, quantum theory allows the energy density to be negative in some places provided it is positive in others.

The reason quantum theory can allow the energy density to be negative is that it is based on the Uncertainty Principle. This says that certain quantities like the position and speed of a particle can’t both have well-defined values. The more accurately the position of a particle is defined the greater is the uncertainty in its speed, and vice versa. The Uncertainty Principle also applies to fields like the electromagnetic field or the gravitational field. It implies that these fields can’t be exactly zero even in what we think of as empty space. For if they were exactly zero their values would have both a well-defined position at zero and a well-defined speed which was also zero. This would be a violation of the Uncertainty Principle. Instead the fields would have to have a certain minimum amount of fluctuations. One can interpret these so-called vacuum fluctuations as pairs of particles and antiparticles that suddenly appear together, move apart and then come back together again and annihilate each other.

These particle–antiparticle pairs are said to be virtual because one cannot measure them directly with a particle detector. However, one can observe their effects indirectly. One way of doing this is by what is called the Casimir effect. Imagine that you have two parallel metal plates a short distance apart. The plates act like mirrors for the virtual particles and anti-particles. This means that the region between the plates is a bit like an organ pipe and will only admit light waves of certain resonant frequencies. The result is that there are a slightly different number of vacuum fluctuations or virtual particles between the plates than there are outside them, where vacuum fluctuations can have any wavelength. The difference in the number of virtual particles between the plates compared with outside the plates means that they don’t exert as much pressure on one side of the plates compared with the other. There is thus a slight force pushing the plates together. This force has been measured experimentally. So, virtual particles actually exist and produce real effects.

Because there are fewer virtual particles or vacuum fluctuations between the plates, they have a lower energy density than in the region outside. But the energy density of empty space far away from the plates must be zero. Otherwise it would warp space–time and the universe wouldn’t be nearly flat. So the energy density in the region between the plates must be negative.

We thus have experimental evidence from the bending of light that space–time is curved and confirmation from the Casimir effect that we can warp it in the negative direction. So it might seem that as we advance in science and technology we might be able to construct a wormhole or warp space and time in some other way so as to be able to travel into our past. If this were the case it would raise a whole host of questions and problems. One of these is if time travel will be possible in the future, why hasn’t someone come back from the future to tell us how to do it.

Even if there were sound reasons for keeping us in ignorance, human nature being what it is it is difficult to believe that someone wouldn’t show off and tell us poor benighted peasants the secret of time travel. Of course, some people would claim that we have already been visited from the future. They would say that UFOs come from the future and that governments are engaged in a gigantic conspiracy to cover them up and keep for themselves the scientific knowledge that these visitors bring. All I can say is that if governments were hiding something they are doing a poor job of extracting useful information from the aliens. I’m pretty sceptical of conspiracy theories, as I believe that cock-up theory is more likely. The reports of sightings of UFOs cannot all be caused by extra-terrestrials because they are mutually contradictory. But, once you admit that some are mistakes or hallucinations, isn’t it more probable that they all are than that we are being visited by people from the future or from the other side of the galaxy? If they really want to colonise the Earth or warn us of some danger they are being rather ineffective.

A possible way to reconcile time travel with the fact that we don’t seem to have had any visitors from the future would be to say that such travel can occur only in the future. In this view one would say space–time in our past was fixed because we have observed it and seen that it is not warped enough to allow travel into the past. On the other hand the future is open. So we might be able to warp it enough to allow time travel. But because we can warp space–time only in the future, we wouldn’t be able to travel back to the present time or earlier.

This picture would explain why we haven’t been overrun by tourists from the future. But it would still leave plenty of paradoxes. Suppose it were possible to go off in a rocket ship and come back before you had set off. What would stop you blowing up the rocket on its launch pad or otherwise preventing yourself from setting out in the first place? There are other versions of this paradox, like going back and killing your parents before you were born, but they are essentially equivalent. There seem to be two possible resolutions.

One is what I shall call the consistent-histories approach. It says that one has to find a consistent solution of the equations of physics even if space–time is so warped that it is possible to travel into the past. On this view you couldn’t set out on the rocket ship to travel into the past unless you had already come back and failed to blow up the launch pad. It is a consistent picture, but it would imply that we were completely determined: we couldn’t change our minds. So much for free will.

The other possibility is what I call the alternative-histories approach. It has been championed by the physicist David Deutsch and it seems to have been what the creator of Back to the Future had in mind. In this view, in one alternative history there would not have been any return from the future before the rocket set off and so no possibility of it being blown up. But when the traveller returns from the future he enters another alternative history. In this the human race makes a tremendous effort to build a spaceship but just before it is due to be launched a similar spaceship, appears from the other side of the galaxy and destroys it.

David Deutsch claims support for the alternative-histories approach from the sum-over-histories concept introduced by the physicist Richard Feynman. The idea is that according to quantum theory the universe doesn’t just have a unique single history. Instead the universe has every single possible history, each with its own probability. There must be a possible history in which there is a lasting peace in the Middle East, though maybe the probability is low.

In some histories space–time will be so warped that objects like rockets will be able to travel into their pasts. But each history is complete and self-contained, describing not only the curved space–time but also the objects in it. So a rocket cannot transfer to another alternative history when it comes round again. It is still in the same history which has to be self-consistent. Thus despite what Deutsch claims I think the sum-over-histories idea supports the consistent-histories hypothesis rather than the alternative-histories idea.

It thus seems that we are stuck with the consistent-histories picture. However, this need not involve problems with determinism or free will if the probabilities are very small for histories in which space–time is so warped that time travel is possible over a macroscopic region. This is what I call the Chronology Protection Conjecture: the laws of physics conspire to prevent time travel on a macroscopic scale.

It seems that what happens is that when space–time gets warped almost enough to allow travel into the past virtual particles can almost become real particles following closed trajectories. The density of the virtual particles and their energy become very large. This means that the probability of these histories is very low. Thus it seems there may be a Chronology Protection Agency at work making the world safe for historians. But this subject of space and time warps is still in its infancy. According to a unifying form of string theory known as M-theory, which is our best hope of uniting general relativity and quantum theory, space–time ought to have eleven dimensions, not just the four that we experience. The idea is that seven of these eleven dimensions are curled up into a space so small that we don’t notice them. On the other hand the remaining four directions are fairly flat and are what we call space–time. If this picture is correct it might be possible to arrange that the four flat directions get mixed up with the seven highly curved or warped directions. What this would give rise to we don’t yet know. But it opens exciting possibilities.

In conclusion, rapid space travel and travel back in time can’t be ruled out according to our present understanding. They would cause great logical problems, so let’s hope there’s a Chronology Protection Law to prevent people going back and killing their parents. But science-fiction fans need not lose heart. There’s hope in M-theory.

Is there any point in hosting a party for time travellers? Would you hope anyone would turn up?

In 2009 I held a party for time travellers in my college, Gonville and Caius in Cambridge, for a film about time travel. To ensure that only genuine time travellers came, I didn’t send out the invitations until after the party. On the day of the party, I sat in college hoping, but no one came. I was disappointed, but not surprised, because I had shown that if general relativity is correct and energy density is positive, time travel is not possible. I would have been delighted if one of my assumptions had turned out to be wrong.