15

THE KPD AND FILM: FROM STUBBORN PERSEVERANCE TO ELEVENTH-HOUR EXPERIMENTS WITH ALTERNATIVE FORMS OF PRODUCTION AND RECEPTION

While the KPD assumed a new leftist course based on the concept of social fascism, the party’s cultural activists intensified efforts to gain leadership positions in existing working-class cultural organizations and to establish as well as expand their own organizations. In October 1928 a group of leftist and KPD authors founded the Bund Proletarisch-Revolutionärer Schriftsteller (Federation of Proletarian Revolutionary Authors, BPRS), and in August 1929 they began publishing their own journal, Die Linkskurve.1 At the end of 1928 the more radical members of the VFV accused their leaders of reformism, and a member of the IAH, Erich Lange, replaced Franz Höllering as the chief editor of Film und Volk. In October 1929 the KPD founded the Interessengemeinschaft für Arbeiterkultur (Interest Group for Workers’ Culture, IfA) to coordinate the party’s cultural activities. In August 1930 party leaders expressed their intention to pay even greater attention to cultural activity as a component of what they referred to as the program for the national and social liberation of the German people.2 During the same period, the IAH sustained and even expanded its already impressive network of cultural organizations and publications.3

THE CONTINUING DEBATE ABOUT MARXIST AESTHETICS

The process continued, as did the debate about a Marxist aesthetics. At this point, very few participants in the ongoing discussion about proletarian culture insisted that such a culture depended entirely on the establishment of a socialist state.4 Most agreed that the dominant culture in Weimar society legitimized less democratic, more exploitive social structures by promoting a regressive ideology associated with the Prussian monarchy. They also agreed that, while concentrating on political work, the revolutionary working class, led by the KPD, must combat all manifestations of the dominant ideology if it hoped to change the ideological orientation of noncommunist workers and transcend the existing social system.

Although Communist cultural activists and those associated with the KPD generally agreed about the goal of their efforts, discussion about the quality of proletarian art continued, now focusing increasingly on the relationship between production and reception.5 Toward the end of the Weimar Republic well-known KPD authors such as Johannes R. Becher, who perceived Marxism above all as a system of analysis with which the revolutionary working class could discern the laws of social development, promoted art as a medium for communicating insights to noncommunist workers.6 Influenced in part by the emerging socialist-realist movement in the Soviet Union, Becher believed that art should convey a Marxist image of pressing social issues in a way that would allow proletarians to understand the process of social development and enable them to influence the process to fulfill their individual and collective needs. Becher and many other proponents of socialist realism commented almost exclusively on questions of content and only tangentially discussed aesthetic form.7 While affirming the new concept of realism, others, including George Lukács, Friedrich Wolf, and Béla Balázs, paid more attention to forms of aesthetic communication and promoted an Aristotelian model of catharsis. Novels, dramas, films, and other art forms, they argued, should portray typical figures from opposing social classes in contemporary society and employ techniques of expression capable of motivating audiences to sympathize with proletarian victims of social injustice who struggle for change.8 A third group of participants in the discussion, theoreticians and artists who shared the desire to challenge the ideological orientation of the dominant German culture, promoted those forms of artistic expression that were deemed capable of reflecting reality most authentically and providing a conceptual image of social totality. For example, Egon Erwin Kisch relied heavily on reportage techniques, John Heartfield experimented with techniques of photomontage, and Erwin Piscator integrated documentary film footage into his stage presentations. They encouraged audiences to reject traditional concepts of social organization and development, internalize a Marxist viewpoint, and adopt the KPD’s program for social change. Instead of appealing to the emotions of their audiences, they hoped to stimulate intellectual activity.

In contrast to each of the groups mentioned above, a final group, including Hanns Eisler and Bertolt Brecht advocated a radical departure from the traditional separation between production and reception. Influenced by radically democratic communists such as Karl Korsch and by members of the Soviet avant garde, including Sergei Tretjakov and remnants of the Proletkult movement, Eisler and Brecht challenged fundamental elements of the institution of art—professionalism, commercial entertainment, narrative cohesion, and emotional engagement. They argued that such elements established and reinforced the notion that only a small group of the most talented artists should produce art. Consequently, they asserted, an artists’ elite assumed responsibility for organizing everyday experience into ideological perspectives for a much larger group of people who were restricted to consuming art and more or less uncritically assimilating the corresponding ideological evaluation. Brecht’s experiments, first with epic theater and later with the Lehrstück, exemplified the development of the tendency among communist cultural theoreticians and artists to reject established techniques of reception and develop radically democratic models of artistic production as a means for the ideological organization of everyday experience.9

FILM CRITICISM IN THE COMMUNIST PRESS

In contrast to the SPD newspapers and journals, the KPD and IAH publications sustained their broad coverage of mainstream cinema as well as their own film activity. Only Die Rote Fahne struggled to maintain consistent coverage in 1931 and 1932 when the Brüning and Papen governments regularly censored it. Generally, the editors of Die Rote Fahne printed articles on cinema in the feuilleton and sporadically included a “Theater und Film” section. In 1931 the heading changed to “Film und Bühne” (“Film and Stage”) and appeared even less regularly. In June/July 1932 the feuilleton slowly gave way to more articles about the escalating political struggle.

At the same time, the less blatantly partisan IAH newspapers avoided censorship and persevered with their coverage. Die Welt am Abend and Berlin am Morgen retained large feuilleton sections, frequently printed articles on cinema, and, like Die Rote Fahne, included special “Theater und Film” sections. Only the AIZ paid less attention to mainstream film than to KPD, IAH, and Soviet film activity. As had been the case previously, most AIZ articles on film publicized Soviet, Prometheus, Weltfilm, and VFV films. Exceptions included reviews of individual films, such as Lilli Kaufmann’s critique of Comradeship (49, 1931), and reports on developments within the commercial film industry, such as Kaufmann’s “Die Traumfabrik der Angestellen” (“The Dream Factory of the White-Collar Workers,” 27, 1932).

Each of the tendencies outlined in the previous section found some expression in the coverage of cinema in the Communist press. The coverage in most Communist newspapers in many ways continued to emphasize the communication of insight from above. Recommending film to their readers is just one example. Die Rote Fahne continued printing its “Films of the Week”; Die Welt am Abend and Berlin am Morgen made suggestions under the heading “Filme, die man sehen soll” (“Films That One Should See”); and the AIZ experimented with its own rubric, “Die Welt der weissen Wand” (“The World of the White Screen,” 23, 1931). As the AIZ explained: “In this space the AIZ regularly will provide an overview of the most important new films so that our readers do not have to risk falling prey to ostentatious advertising.” Unlike the corresponding projects in other newspapers, the AIZ program ceased after one issue, and the newspaper devoted its energy to promoting Soviet, IAH, and VFV films.

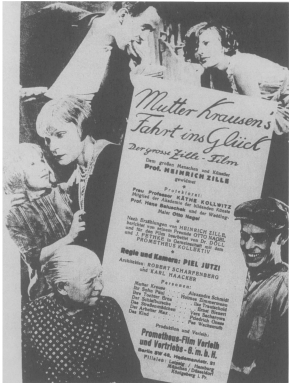

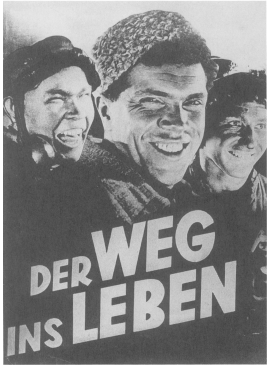

In addition to recommending films openly, each newspaper followed the AIZ model, directing attention to specific films by reporting on their production and by featuring articles on topics related to their themes. During the fall of 1929, for example, a number of articles, including “Ein Zille-Film im Werden” (“A Zille Film in Production,” Die Welt am Abend, 7 November 1929), “Wie der Zille-Film gedreht wird” (“How the Zille Film Is Being Produced,” Berlin am Morgen, 9 November 1929), “Der richtige Zille-Film” (“The True Zille Film,” Die Rote Fahne, 5 December 1929), and “Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück” (“Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness,” AIZ, 52, 1929), publicized the efforts of Prometheus to produce its film in commemoration of Heinrich Zille’s death. With articles such as “Kinderhölle Sowjetrußland” (“Children’s Hell in Soviet Russia,” Berlin am Morgen, 25 January 1931) about the treatment of juvenile delinquents in the Soviet Union and Der Weg ins Leben (The Way into Life, the first Soviet sound film distributed in Germany), the Communist newspapers continued their campaign to generate interest in films they considered worthwhile. They did so by associating the fictional protrayals with existing social problems. Such articles advocated cinematic realism, ascribed authenticity to the featured film, and encouraged potential spectators to accept the corresponding ideological orientation.

The articles on commercial film in general and the authoritative reviews that appeared in the KPD and IAH newspapers provided much more powerful and explicit guidelines. Between 1929 and 1933 each newspaper relied on a small group of highly active journalists for film articles and reviews. Alfred Durus wrote many substantial articles and reviews for Die Rote Fahne. Kurt Kersten and Michael Mendelssohn contributed most frequently to Die Welt am Abend. F. C. Weiskopf, the feuilleton editor of Berlin am Morgen, Mersus (pseudonym?), and Hans Tasiemka shared responsibility for that newspaper’s film coverage. Heinz Lüdecke contributed articles to all of the newspapers cited. Most AIZ articles appeared anonymously, but in 1932 Lilli Kaufmann emerged as that newspaper’s film journalist. Each of the major contributors held a position of authority, communicating insights about the industry as unquestionable truths and positing general standards for film evaluation.

A major focal point remained the influence of right-leaning interest groups on commercial cinema. As the transition to sound progressed, articles such as “Hugenbergisierung des Tonfilms” (“Hugenbergization of Sound Film,” Die Rote Fahne, 13 April 1929) discussed the ways in which the largest concerns used the innovation to increase their ideological control of the entire industry. Other articles, including “Die Ufa macht Politik” (“Ufa Politicizes,” Berlin am Morgen, 9 July 1929) and “Kleiner Wahlfilm” (“Little Campaign Film,” Die Rote Fahne, 13 March 1932), highlighted the explicit political activity of Ufa, Tobis, etc., to expose their ideological orientation. Contributors also criticized the ongoing manipulation of film criticism by producers and promoted journalistic independence (“Unabhängige Filmkritik”—“Independent Film Criticism,” Die Rote Fahne, 5 November 1930; and “Um die Freiheit der Filmkritik”—“For the Freedom of Film Criticism,” Berlin am Morgen, 4 January 1931).

Censorship decisions, especially after the prohibition of All Quiet on the Western Front, received even more attention. In articles such as “Die Filmzensur muß fallen!” (“Film Censorship Must Fall!” Berlin am Morgen, 9 December 1930) and “Filmzensur wütet” (“Film Censorship Rages,” Die Rote Fahne, 20 January 1931), contributors compared decisions on numerous films, noting that nationalistic and militaristic films passed while pacifistic and socialistic films were censored. The critics claimed that the government had begun to support cultural fascism openly.10

The articles on censorship reveal a second focal point of film coverage in the Communist press. When comparing the censors’ decisions, contributors normally evaluated the films in question. As had been the case prior to 1929, they often accused mainstream filmmakers of falsifying history and perpetuating the myth of upward social mobility. Now they also more frequently distinguished general trends in production and referred at least vaguely to the relationship between production and reception. In “Rezept für Tonfilmpossen” (“Recipe for Sound Film Farces,” Die Rote Fahne, 27 November 1931), for example, Heinz Lüdecke outlined the impact of standardization on production, suggesting that economic as well as political considerations influenced the quality of commercial film. Although individual film critics did recognize the influence of standardization on plotlines, it is important to note that its influence on production techniques and the effect on reception attracted almost no attention.

Between 1929 and 1933 those critics who consistently discussed audience reception more often criticized the cinematic appeal to the emotions. Michael Mendelssohn, in his review of Cyankali (Die Welt am Abend, 24 May 1930), exemplified the trend. According to Mendelssohn, Hans Tintner’s adaptation of Friedrich Wolf’s abortion tragedy only imitated the commercial techniques of catharsis. Although Mendelssohn and others criticized what they perceived as a manipulative emotional appeal, they rarely discussed in any detail how photographic techniques, montage, or sound generated and guided emotional responses. Instead of offering concrete evidence, in most cases they merely asserted their authority as experts. Mendelssohn’s review also indicated that whereas the IAH newspapers originally moderated their criticism of commercial film to attract a broader, nonpartisan readership, the critical quality of their reviews now differed little from those of Die Rote Fahne.

In addition to guiding reception with its reviews, Die Rote Fahne, like the SPD Vorwärts, occasionally published stories about commercial films with a moral. E. Fritz, for example, narrated a story, “Kientopp” (“Nickelodeon,” 12 May 1932), about a worker who temporarily escapes into the dreamworld of cinematic entertainment but then must return to the everyday world of exploitation, anxiety, and frustration. Like K. R. Neubert’s “Farewell after a Film,” Fritz’s story instructed workers to reject cinematic entertainment and to strive for real social change. Die Rote Fahne also printed articles with titles from commercial films, such as “Drei von der Stempelstelle” (“Three from the Unemployment Line,” 8 April 1932), and claimed to contrast cinematic fiction with reality. In this case the article referred to a film which invited the unemployed to trust resettlement schemes. While recalling the film, the article reported stories of three real unemployed workers who rejected the film’s invitation, demanded work, and supported the KPD.

The attempt to draw a connection between leftist cinematic fiction and reality and the challenge to the authenticity of mainstream cinematic fiction demonstrated the general allegiance to the new concept of socialist realism among Communist film journalists. Alfred Durus reinforced the perception in his “Der Tonfilm, wie er ist und sein soll” (“Sound Film as It Is and as It Should Be,” Die Rote Fahne, 25 June 1929). He asserted, “Sound film is most important as a medium for intensifying the power of realism in the revolutionary documentaries.” Most of the regular contributors to the KPD and IAH newspapers perceived proletarian film as an element in the KPD’s agitational work (Kampfkultur). They generally applauded emotional and intellectual approaches as long as filmmakers portrayed realistic struggles between typical figures from contemporary social classes, fostered a Marxist understanding of social totality, and encouraged audiences to participate in revolutionary social change.

While KPD and IAH journalists criticized commercial films as “sentimental” and “pathetic,” they praised a similar aesthetic orientation in Soviet and Prometheus films as “gripping” and “compelling.” The distinguishing feature was content. Films like Cyankali were unacceptable because their victimized working-class protagonists struggled unsuccessfully against social oppression. Such films evoked sympathy for proletarian heroes and perhaps even contributed to a Marxist understanding of social totality, but they provided no clear-cut guidelines for social change. Soviet films, on the other hand, won widespread acclaim among Communist critics by closely following the socialist-realist formula. As a review of Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia in Die Rote Fahne (8 January 1929) explained: “The whole Mongolian world comes alive on the eve of its liberation. The barbarism of the White Guard officer’s camarilla, the reactionary religious cult of the ‘living Buddha,’ and the misery of the plundered, deceived, and mistreated hunters and shepherds are shaped into the forces of play and counterplay from which inevitably and irresistibly the revolutionary conclusion, the tremendous compelling storm of freedom, the ’storm over Asia,’ arises.”

Many critics preferred Pudovkin’s emotional appeal to Eisenstein’s experiments with intellectual stimulation. But they criticized Eisenstein’s experiments only when they failed to meet the standards for socialist realism. The review of Eisenstein’s Der Kampf um die Erde (The Struggle for the Earth, Die Rote Fahne, 12 February 1930) by Alfred Durus provides a good example; in it Durus notes: “Eisenstein wishes to assemble thoughts, but often only assembles images and ‘emotions’ where clear Marxist-Leninist thought patterns would be indispensable.”

The reviews of Soviet and Prometheus films were often more extensive than those of mainstream films. They also included somewhat more detailed information about narrative techniques. Here, as well, the critics preferred narrative cohesion and cinematic catharsis but accepted experiments designed to stimulate intellectual activity as long as the ideological orientation associated with the plot was acceptable. Soviet films that portrayed the socialist construction were among the best films, according to Durus. His reviews in Die Rote Fahne of Turksib (29 December 1929), The Struggle for the Earth (12 February 1930), and Enthusiasm (26 August 1931) praised Soviet filmmakers for portraying examples of socialist construction with vivid authenticity and implied that such cinematic achievements were only possible under socialist conditions. Durus no longer intended to suggest that proletarian art was impossible in Germany, but he, F. C. Weiskopf, and others did present the Soviet Union and its cinema as models for German social and cinematic development. In each review Durus also praised the portrayed accomplishments of Soviet industry and agriculture, affirming the conquest of nature and asserting that under socialism humanity could accelerate its progress toward that goal (“Turksib,” Die Rote Fahne, 29 December 1929).

Communist journalists during the final crisis years generally communicated insights about mainstream cinema and about their own film organizations in an authoritarian manner. They promoted film as a medium to educate the working masses about social development from the KPD perspective and to reinforce the model quality of the Soviet Union. They did not encourage readers to practice their own analytical skills and to engage in critical interaction with filmmakers, critics, and the films themselves. As the reviews of Soviet films by Alfred Durus demonstrate, Communists concentrated foremost on marketing the Soviet model.

There were apparent exceptions: Die Rote Fahne and Berlin am Morgen initiated limited campaigns to involve readers more in film criticism and production. For example, the KPD’s Arbeiterkorrespondenten (worker correspondents) regularly submitted short reviews to Die Rote Fahne. As the newspaper explained: “In Germany all cultural correspondents of the Arbeiterkorrespondenten in Die Rote Fahne are part of our campaign to stimulate the creative initiative of the masses in the struggle against bourgeois ideology even before we assume power” (“Rotarmisten über Ermlers Films”—“Red Guards on Ermler’s Film,” 16 April 1930). The reviews of the Arbeiterkorrespondenten created the perception that grass-roots initiatives contributed significantly to the KPD’s film program. The perception was at least partially false. Die Rote Fahne editors did encourage the Arbeiterkorrespondenten to participate, but their suggestions often took the form of directives from above. In “Filmkritik” (“Film Criticism,” 10 September 1929), an Hungarian emigrant described his initiative in the following manner: “I received a ticket from Die Rote Fahne, with instructions to see an Hungarian film in the Primus Palast and to write a critique of it.” A short time later a more experienced correspondent indicated even more clearly the relationship between the editors and the correspondents. In “Statt einer Filmbesprechung” (“Instead of a Film Review,” 8 October 1929) the correspondent expressed appreciation to Die Rote Fahne for sending him tickets to a premiere but explained that he had joined a boycott of the performance with striking workers at the theater. The correspondent closed by apologizing for not submitting a review.

Berlin am Morgen relied exclusively on a core of experienced journalists for its articles on cinema and reviews. But in 1932 the newspaper began to encourage readers to participate more creatively in film production. In “Wer schreibt den besten sozialistischen Film?” (“Who Will Write the Best Socialist Film Script?” 2 June 1932) the editors announced their cooperation with Meschrabpom in a campaign to solicit exposés and scripts from readers. And in “Hallo, alle kommen mit” (“Hey, Everyone’s Coming Along,” 14 July 1932) they invited readers to attend a steamship cruise. During the cruise, passengers would generate ideas for a film script cooperatively. At approximately the same time, other articles, including “Warum Schmalfilm?” (“Why 8-mm Film?” 23 June 1932) and “Mit der Kamera in die Zeltstadt” (“Into the Tent Colony with the Camera,” 9 August 1932), discussed the introduction of 8-mm film and its use by independent working-class collectives. The Meschrabpom contest, the steamship cruise, and the reports about grass-roots work with 8-mm film at least appeared to be more genuine attempts to challenge existing concepts of production and reception and to encourage readers to initiate their own projects.

It is important to note that the reviews of the Arbeiterkorrespondenten and the new approach in Berlin am Morgen were relatively isolated phenomena that coincided with the experience of crisis. When the KPD reevaluated its political strategy and abandoned the concept of social fascism in 1932, it is likely that cultural leaders also grew more susceptible to proposals for radically democratic cultural alternatives. As the popularity of National Socialism increased and the economic crisis intensified, the KPD leadership perhaps became more sensitive to criticisms and proposals from its political and cultural left wing. Ernst Thälmann had expressed the need to strengthen the democratic process within the party in response to criticism from Berlin delegates at the district party convention as early as May 1930 (“Genosse Thälmann über Selbstkritik und Massenarbeit”—“Comrade Thälmann on Self-Criticism and Work with the Masses,” Die Rote Fahne, 27 May 1930). By 1932 the KPD’s cultural leaders seemed willing to accept such criticisms and initiate campaigns to increase the participation of readers and moviegoers in the party’s film program. In January 1933 before they could test the viability of their new approach, Hitler assumed power.

THE FILM-KARTELL “WELT-FILM” GMBH

Between 1929 and 1933 the KPD/IAH film production and distribution programs, like the coverage of film in the Communist press, followed developing trends in Marxist aesthetics. The Film-Kartell “Welt-Film” GmbH (Weltfilm) concentrated exclusively on noncommercial production and distribution, supplying films and guidelines for campaigns and other KPD and IAH events.11 Weltfilm, like the SPD’s FuL, distributed a small number of what it considered to be socially critical mainstream films, but relied heavily on Soviet films and Prometheus films to fill its distribution program. It also produced about thirty short documentary films with screening times of fifteen to twenty-five minutes. As was the case with the SPD’s short documentaries, the films accompanied the feature and depicted KPD and IAH leaders, demonstrations, conventions, and sporting events. Weltfilm documentaries such as Zwölfter Parteitag der KPD in Berlin (Twelfth Party Congress of the KPD in Berlin, 1929), Der erste Mai 1930 in Berlin (May Day in Berlin, 1930), and Rot Sport im Bild (Red Sport in Pictures, 1930) functioned above all to promote the leaders and policies of both organizations to potential voters and sympathizers.

A smaller number of more extensive documentaries opposed dominant ideological perspectives with Marxist analysis. For example, Zeitproblem. Wie der Arbeiter wohnt (Contemporary Problem: How the Worker Lives, 1930), conceived by Weltfilm as the first in a series, challenged the orientation of mainstream newsreels such as Ufa’s Wochenschau. Slatan Dudow, a young Bulgarian who had come to Berlin in 1922 to study drama and film, directed what became the only contribution to the series.12 The film’s abundant omniscient intertitles and simple juxtaposition of contrasting images betrayed Dudow’s inexperience as well as the reductive approach of many German leftists toward documentary filmmaking. The intertitles suggested that corresponding visual images typified miserable living and working conditions for working-class Germans. With paratactic juxtapositions Dudow reinforced the suggested typicality of the misery being portrayed. For example, a selection of close-ups depicting the exhausted, sad faces of individual workers follows a sequence in which masses of workers leave a factory. In another sequence a crowd of people enter a streetcar followed by a single man who checks the ground around him for an unused ticket. After establishing an association between poor, exhausted individuals and the working masses, Dudow contrasted the living conditions of the rich and poor. An intertitle proclaiming “the unwelcome guest” introduces a scene in which a crippled salesman is turned away repeatedly by the occupants of villas and luxury apartments. Then the barracks of the poor appear, and an intertitle asserts “the irreconcilable differences.” The narrative then depicts the living environment of the poor and portrays the police eviction of one family. Juxtaposed with shots of the eviction are close-ups of a fat, smiling bourgeois and the policeman’s helmet. A final intertitle exclaims: “That is no solution!”

How the Worker Lives also exemplified a new trend in the KPD/IAH documentaries. While claiming all the objectivity of documentaries, it incorporated staged scenes such as the eviction to establish class distinctions, evoke sympathy for the poor, generate disdain for the rich, and encourage spectators to reject existing authority. How the Worker Lives employed the documentary medium and the omniscient narrative voice to maximize its authenticity and the authority of the KPD. Like the SPD’s FuL, Weltfilm used films such as Dudow’s documentary and its distribution program to attract support for KPD/IAH leaders and perspectives. It did so in a way that encouraged spectators to rely on authoritarian direction.

PROMETHEUS: THE TRANSITION TO SOUND FILM AND MESCHRABPOM

While Weltfilm administered the noncommercial film programs of the KPD and IAH, Prometheus attempted to adapt to changes in the film industry and remain competitive. Just two weeks after the first major sound film, Melody of the World, had its premiere in Berlin, the leading trade journals announced that Prometheus and Meschrabpom were negotiating with British Phototone, a producer of sound film equipment, to co-produce films. According to the L.B.B, and the Film-Kurier (see reports on 16 April 1929), British Phototone had agreed to co-produce a number of sound films with Prometheus and Meschrabpom, including the next Pudovkin film, Das Leben ist schön (Life Is Beautiful), Das Wolgalied (The Song of the Volga), and Die Premiere with Anna Sten. None of the projects materialized. British Phototone had established an association with the Siemens-Halske Klangfilm company in January (Kinematograph, 22 January 1929). When Klangfilm merged with Tobis in the spring of 1929, it is likely that the Tobis-Klangfilm partnership superseded other agreements. Although Prometheus, Meschrabpom, and British Phototone had an agreement, they were unable to produce sound films independent of the large conglomerate.

Just one week after negotiating the British Phototone agreement, Prometheus and Meschrabpom further solidified their partnership. A report in the L.B.B. (23 April 1929) explained that Meschrabpom had granted Prometheus first access to its films for distribution. The change perhaps anticipated the co-production of sound films, but the increasingly tenuous status of Derussa also might have motivated the closer association between Prometheus and Meschrabpom. In September 1929 Derussa collapsed. It soon became clear that the German partners, the Sklarz brothers, had exploited the Russian Trade Bureau.13 Without Derussa, the Soviet film industry depended even more on Prometheus in 1930 and finally declared the company to be its primary international distributor (L.B.B., 15 October 1930).

In addition to negotiating with British Phototone and working more closely with the Soviet film industry, Prometheus modified its marketing program. Jan Fethke began administering Prometheus publicity in September 1929, and in November he was replaced by Wilhelm Giltmann, an experienced publicity executive for Gaumont who also could speak Russian.14 During the final year in which silent films attracted large audiences, Prometheus used a wide variety of publicity techniques to maximize commercial success. It distributed production information to, and advertised often in, all leading trade journals; it commissioned the Illustrierter Film-Kurier to produce and distribute programs for its features and for many major Soviet films; and according to a report in Die deutsche Filmzeitung (26, 1929), it even experimented with recorded advertisements.

THE LIVING CORPSE

The desire for commercial success continued to influence the choice of subject material for Prometheus films. For their second co-production Meschrabpom and Prometheus selected an adaptation of Tolstoy’s The Living Corpse. In 1928 Max Reinhardt had produced the play about a pathetic Russian bourgeois whose sense of propriety and honor hinder him from divorcing his wife when their marriage deteriorates. The success of Reinhardt’s production almost certainly influenced the Prometheus and Meschrabpom decision to produce an adaptation. Fjodor Ozep, a young Russian who had directed Der gelbe Paß (The Yellow Pass, 1928), wrote the script and directed the film. Pudovkin played the leading role. In contrast to the drama’s emphasis on the protagonist’s psychological struggle, Ozep’s adaptation concentrated on the injustice of the czarist social system.15

The story begins with the melancholic protagonist, Fedja Protassow, expressing his desire for a divorce to a priest in an Orthodox church. The priest refers to the inviolability of the church’s law, explains that Fedja’s case does not warrant divorce, and advises him to bear his cross as must everyone else. Fedja then appears in a bar where Artemjew, a lawyer, claims that, with his assistance, Fedja can pretend adultery and be divorced in no time. The scheme repulses Fedja. He contemplates running away but returns home where he finds his wife at the piano with her lover, Kerenin. Fedja flees to his gypsy friend, the beautiful Mascha, and following a confrontation with Kerenin, who also advises him to simulate adultery, he decides to attempt the deceit. Again the act of adultery repulses Fedja. He finally accepts Mascha’s suggestion to pretend a suicide attempt and begin a new life. The plot succeeds, but Fedja remains despondent. After years of wandering the streets as a living corpse, he reappears in the bar where Artemjew recognizes the lost husband and attempts to involve him in a scheme to blackmail his wife and her new husband. Fedja rejects the offer, and Artemjew betrays him to the police. In a final trial scene Fedja, confronted again by the inflexibility of the law, kills himself.

The Living Corpse: Illustrierter Film-Kurier program cover. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

Unlike earlier Prometheus films, The Living Corpse made little use of omniscient intertitles to establish narrative authority or create the illusion of reality. For the most part intertitles communicated dialogues and occasionally revealed the content of letters from Fedja to his wife. However, Ozep did employ photographic and montage techniques to create a cohesive narrative structure and to guide reception. The reviews emphasized his use of montage, noting its similarity to that of the other Soviet directors. For example, the Vorwärts review (15 February 1929) explained: “Again and again we see the symbolic segments, so favored by the Russians. They represent the state, the church, the law, and remind the audience repeatedly that these are the things that cause all the suffering.” The review accurately describes the narrative orientation but notes only one of many techniques that Ozep used to suggest social totality. The exposition provides an excellent example of Ozep’s narration. The spectator first sees a city scape dominated by church steeples; an intertitle explains: “Moscow, the city of a thousand towers.” The next shot focuses on a single bell tower, and a second intertitle states: “The holy synod of the Orthodox church.” Photography and montage now replace the intertitles in organizing and ascribing meaning to the visual image. The juxtaposition of a cityscape filled with church steeples and a single church’s bell tower alone suggests that the Orthodox church is omnipresent and that the individual church represents them all. A split screen of many ringing bells reinforces the representative quality of the single bell tower, while their motion becomes a transitional element. Next a single incenser is seen inside the church, moving like the many bells and continuing the association between the general and the specific.

At this point the perspective moves outside the church and centers on its giant doors from a low angle. They seem to open automatically, and a short sequence presents still more shots of church steeples and icons of the Orthodox church. Finally, a man emerges as if from within the camera and climbs the stairs toward the entrance. As he climbs, images of religious statues and icons fade in and out. He enters the church, and the camera perspective moves to a high angle behind a priest, allowing the audience to observe the seemingly dwarfed man from above. Similar photographic techniques and montage symbolism organize the remainder of the scene as the man, whom the audience now recognizes as Fedja, communicates with the priest. Ozep’s narration suggests throughout that the church’s authority encompasses and dominates Fedja. Fedja’s emergence from the spectator’s perspective also initiates the association between spectator and protagonist.

In addition to depicting the priest as a cold and powerful representative of church law, Ozep employed an impressive variety of cinematic techniques to characterize most authoritarian figures as unemotional and selfishly calculating, while emphasizing Fedja’s helplessness and encouraging audience sympathy. For example, the narrative juxtaposes the corrupt Artemjew and Fedja, the bigoted Kerenin and Fedja. It reveals the contents of a letter in which Fedja expresses his desire to ensure his wife’s happiness. From an overhead angle the spectator looks down on a miserable Fedja after his pretended suicide. A sequence portraying a man who whips his exhausted horse follows shots of Fedja stumbling through the streets. Recurring shots of caged birds symbolize Fedja’s condition. And parallel montage moves the spectator back and forth between images of Fedja, who begins the simulated adultery or contemplates suicide, and images of the bar, thus building suspense and heightening the spectator’s emotional involvement.

After providing more than ample information for the audience to assimilate emotionally the narrative perspective, Ozep surprisingly disrupts the cohesion of his narrative somewhat and challenges the audience to participate both emotionally and intellectually in the concluding trial section. A symbolic montage sequence initiates the section, recalling the symbols of czarist authority. Following each image an intertitle proclaims: “The Law.” The ensuing sequence depicts a crowd of people climbing a large stairway into a court building. For the first time Ozep composes the shots so that, from an observer’s position, Fedja is perceived to be above those around him. He stands near the top of the stairs, separated by the crowd from his wife below. The statue of justice assumes Fedja’s position, but his wife remains below with the crowd between them. The juxtaposition of Fedja and the statue at the top of each shot indicates that Fedja will no longer submit to the domination of the law, a suggestion that subsequent signals reinforce.

Once inside the courtroom, the camera’s perspective changes periodically but establishes a base with the onlookers’ point of view and draws special attention to the act of observation. Numerous shots present the onlookers, who are dressed formally and suddenly raise opera glasses in unison. This unexpected incongruity suspends the illusion of reality. By associating the audience’s perspective with that of the onlookers, whose appearance and behavior are more like that of spectators at a cultural event than the gallery at a trial, it disturbs the audience’s emotional engagement and invites them to participate intellectually in the decision-making process. The onlookers, lawyers, and Fedja take their places, but the judges’ and jurors’ seats remain empty. An intertitle announces: “The Law.” Suddenly the judges and jurors appear. The intertitle solidifies the association between the general symbols of czarist authority and the specific authority of the court. The sequence further disrupts the illusion of reality, reminding spectators of the fiction.

As the trial begins, a high-angle establishing shot from behind the judges directs the audience’s view down on Fedja, with onlookers behind him. The perspective returns for most of the proceedings to the judges’, jurors', and onlookers’ positions. A dialogue develops between the judges and Fedja, who challenges their authority by looking directly at them (and at the audience) and asserting: “Only a divorce could resolve these tensions—freedom! But you block the way to this freedom with countless obstacles.” Fedja continues, but one of the judges rings a bell and ends Fedja’s challenge. The judge’s image slowly dissolves into the image of Fedja and supersedes it.

Now the public prosecutor presents his arguments, claiming the law’s authority over the will of individuals: “And the law remains firm: in the interest of the state it demands punishment for every crime.” Images of czarist authority accompany his arguments, and when the defense attorney questions the definition of crime and criminals, images of nature and the statue of Venus appear. The courtroom then empties as a theater would at intermission. While the jurors deliberate, Fedja (and the audience) learn that he will be exiled to Siberia or forced to resume his marriage. As the deliberation continues, Artemjew appears and gives Fedja a gun. The sequence then shifts between a scene of the judges and onlookers enjoying a feast and high-angle views of Fedja alone in the courtroom. The juxtaposition builds suspense until spectators see a judge suddenly jump, indicating a shot has been fired. Everyone rushes to Fedja who lies motionless on the floor. Images of Fedja and the familiar symbols of authority conclude the scene.

As the suicide sequence illustrates, although Ozep at least partially suspended the illusion of reality and encouraged the audience to contemplate the arguments raised during the trial, the narration also reinforced his image of social totality and reestablished the spectators’ emotional association with Fedja. Ozep revealed the fictional quality of his portrayal and invited spectators to consider its significance for their everyday lives, but provided sufficient information to influence if not control their contemplation. The Living Corpse challenged spectators to condemn social systems in which authority and its representatives are cold, inflexible, bigoted. It asked them to sympathize with honest, compassionate individuals who are victimized by the system.

For German audiences in 1929 The Living Corpse was particularly relevant. In 1928 the German parliament had renewed a debate about divorce regulations that had begun in 1921.16 The existing regulations were almost as strict as those described by the priest at the beginning of the film. In most cases, they allowed divorce only if a partner could be found guilty of malicious abandonment, extreme persecution, or adultery. A proposed reform would have permitted a partner to file for divorce based on irreconcilable differences, but the Catholic Center party campaigned successfully against it. Considering the easily discernible parallel to the contemporary social context and the rejection of Counterfeiters in January 1929, it is likely that Prometheus masked its social critique and moderated it, allowing Fedja to commit suicide instead of attempting to initiate social change. Even so, the censors reviewed the film twice and removed almost six hundred meters before releasing it for public screening. Critics and audiences responded positively, and The Living Corpse became Germany’s tenth most popular film for the first quarter of 1929 (“Die besten Filme seit Januar 1929”—“The Best Films since January 1929,” Film-Kurier, 5 April 1929).

The most popular film at the beginning of 1929 was another film distributed by Prometheus, Pudovkin’s Storm over Asia. On 26 January 1929 the Marmorhaus in Berlin celebrated its fiftieth sold-out screening of the film, and according to an advertisement in Film-Kurier (26 January 1929), two hundred Berlin theaters were screening Storm over Asia. It was within the context of increasing commercial success that Prometheus negotiated with British Phototone, contemplated the construction of a film studio in Berlin, and announced plans to produce impressive sound films, featuring directors such as Ozep and Pudovkin plus stars like Anna Sten. A short time later, following the Tobis-Klangfilm merger, Prometheus realized that it would be unable to join major German producers in their transition to sound film. The company modified its plans and concentrated on the production and marketing of what it hoped would be commercially successful silent films.

BEYOND THE STREET

The success of Storm over Asia and The Living Corpse enabled Prometheus to produce its next film without assistance from Meschrabpom. The Prometheus executives commissioned Alfred Tuscherer, the brother-in-law of Kurt Bernhardt and his assistant in Schinderhannes, to manage production. Jan Fethke, who also supervised publicity, and Willi Doll wrote the script. Leo Mittler, a stage director with limited film experience, directed the film. As the title suggests, Fethke and Döll based their script on the commercially successful street films. Economic and political interests influenced the thematic orientation.17

Beyond the Street presents the story of a young unemployed man, an older beggar, and an attractive prostitute who are drawn together by a pearl necklace. The story begins with the young man. He meets the beggar and describes his unsuccessful search for work. The beggar sympathizes and invites him to stay in his dilapidated houseboat. The young man accepts and spends his days looking for work while his older friend sits on street corners, pretends to be blind, and solicits donations with his music box.. One day the beggar watches an elegantly dressed woman drop a pearl necklace on the street. He recovers the necklace and tries to conceal it before anyone notices. But a prostitute observes the event and, although she leaves, is unable to forget what she has seen. Later, after an especially prosperous day, the beggar invites the young man to a neighborhood bar. There they see the prostitute. She recognizes the beggar and dances with the young man. He eventually rescues her from a drunken sailor, and she takes him home with her. The next morning the prostitute prepares breakfast for her new lover and offers to share her apartment with him. Just then the landlady interrupts them and demands payment. The prostitute gives her some money, promises to deliver the rest that night, and then dresses for work. Only now does the young man realize that he has fallen in love with a prostitute. He promises to free her from prostitution, and when she asks how, he mentions the beggar’s necklace. The prostitute offers to sell it to a friend, suggesting that they all will profit from the sale. When the young man explains the proposition to the beggar, he rejects it vehemently, and the young man must return to his lover with the bad news. She becomes cynical and exclaims: “Leave me alone! It doesn’t matter anyway. You can’t really get out of this filth.” The young man flees, wanders through the streets, and eventually returns to the houseboat. There he fights with the beggar, then chases him along the waterfront. The beggar falls into the water and drowns while clinging to his pearl necklace.

Beyond the Street: Illustrierter Film-Kurier program cover. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

Beyond the Street: the prostitute and the young man meet in a neighborhood bar. (Stiftung Deutsche Kinemathek)

The story differed significantly from those of earlier street films. Unlike films such as The Street and Tragedy of a Prostitute with their emphasis on middle-class protagonists, Beyond the Street presented working-class and lumpen-proletarian protagonists.18 Instead of portraying them as inherently and unalterably criminal inhabitants of a self-perpetuating evil world, it suggested that the existing social system forced compassionate and honest people to adopt criminal methods of survival. Beyond the Street challenged the portrayal of the street in mainstream films by positing an image of social totality. According to its image, affluence and poverty coexisted in an interdependent relationship. And some of the impoverished rejected the consequences of the relationship for themselves but were unable to initiate change.

The narrative employed numerous techniques to convince spectators that its image of the street was more authentic and more representative than that of previous street films. Except for Lissi Arna, who played the prostitute, the actors were relatively unknown, and the characters were nameless. Beyond the Street encouraged spectators to accept its characters as types, not as unique individuals. In addition, documentary film footage of bustling harbor scenes, busy urban streets, and tenement housing areas suggested its characters were authentic inhabitants of contemporary society. However, the most effective element of the narrative’s realism was its frame story.

Before the unemployed young man and the beggar meet, a well-constructed framing segment introduces the characters and plot. It does so in a way that suggests authenticity and typicality while stimulating curiosity. The frame begins with an establishing shot of a sidewalk café. The camera slowly tracks in to the café, makes its way between the tables, and stops behind a cigar-smoking man with a newspaper. The perspective allows the spectator to read the following headlines with him: “Last speech by Poincaré in Geneva,” “Express Train Catastrophe,” and “Boxing Match for the Heavyweight Title.” An accompanying intertitle draws a connection between the individual headlines and the general course of events: “Newspaper copies in the millions… daily. Ten thousand stories… daily. Ten thousand fates, and who thinks about it between a mocha and a cigar?” The intertitle suggests that newspaper readers like this one have little concern for the individual stories.

The newspaper slowly rises, and beneath it the man (and the audience) can see the slender legs of a woman. During the following sequence, the camera first assumes an observer’s perspective, allowing spectators to watch as the man moves his newspaper to one side and begins to flirt. At this point he can be identified as the well-dressed, overweight caricature of a Prussian bourgeois. In the next shot, the camera returns to his perspective and scans the woman’s body from her waist down. Then the perspective resumes a position behind him, from which spectators watch the newspaper rise again. A close-up depicts the woman as she seductively crosses her legs. Now the man straightens his newspaper and reads an article: “Murder or accident? This morning the corpse of a man was pulled from the water at the Paris Bridge. His meager clothing was so badly torn in places that officials suspect he was in a fight. Remarkable in this regard is that the old man…” Finally, the camera tracks in on the last phrase of the interrupted report: “the old man…”

As the framing segment reveals, Fethke, Doll, and Mittler constructed a tightly knit narrative with conventional photographic and montage techniques to introduce the main plot. Infrequent omniscient intertitles and the newspaper suggest its authenticity and typicality, but the primary signifiers are the images and their presentation. Costumes, gestures, camera angles and perspectives, as well as montage indicate the attitude of the bourgeois man and identify the woman as a prostitute. By interrupting the story about the old man and formulating the headline as a question, the narrative stimulates curiosity. The track-in to the last phrase provides a transitional element from the frame to the main plot.

The next scene begins with a low-level street shot, depicting the swiftly moving legs of passing pedestrians. The perspective slowly moves along the curb, through the legs, and stops before the old beggar with his music box. The reference to the old man at the end of the frame and his appearance now suggest that the newspaper article was about this beggar. The juxtaposition of the anonymous legs of the passing pedestrians and the motionless old beggar suggests that the quick pace of modern society inhibits interpersonal contact and compassion. Like the disinterested newspaper reader, the pedestrians show no concern for the beggar. Suddenly, a small child emerges from the stream of pedestrians and watches with amazement as the beggar plays his music box. Although frightened by his expressionless face, the child shyly places a coin in the beggar’s hat. Following a close-up of the hat, the beggar prepares to acknowledge the gift mechanically, but then returns the coin to the child with a smile. The child buys some ice cream with the coin and disappears into the traffic. As the scene concludes the beggar collects his gear, stands, and slowly crosses the street, intersecting the flow of traffic. A short symbolic sequence, including images of rhythmically moving plant life and water reflections, punctuates his movement and strengthens the contrast between the bustling pedestrians and the lethargic beggar. It also offers a transition to the location of the next segment: the rural environment of the beggar’s home.

With absolutely no intertitles, the narration (which bears a striking resemblance to Eisenstein’s in the street scenes of Battleship Potemkin) establishes a clear contrast between a fast-moving, anonymous, and unfeeling society and the compassionate, slow-moving beggar. It also initiates the audience’s emotional connection with the film’s protagonists while reinforcing a negative image of the existing social system. In the following scene, the beggar demonstrates his compassion again by offering to share his houseboat. Later, the prostitute expresses her dissatisfaction with her profession and her wish to develop a sincere, loving relationship. And the young man searches incessantly for employment. But in the end, the necklace destroys the relationships between all of them.

When the beggar sinks into the water, still clinging to the necklace, images of asphalt fade in, replacing those of water. The narrative now returns to the café and resumes the frame story. The bourgeois man continues reading the article, as the audience reads along: “Remarkable in this regard is that the old man held a pearl necklace in his fist which, upon closer inspection, turned out to be a worthless imitation. The suspect is a young unemployed man who lived with the old man. He has not been seen since yesterday.” Beneath the article is an advertisement for a widower’s ball. The man circles it with a pencil, shows it to the woman at the next table, and says: “There’s where we’ll go.” For the first time the spectator sees the woman’s face and realizes that she is the prostitute of the main plot. In the concluding sequence, the bourgeois and his escort emerge from the stream of pedestrians. The man’s stomach completely overshadows his companion’s figure. While he flirts, her glance comes to rest on the spot where the beggar sat. Her facial expression reveals the sad memory of what has transpired. As she and her admirer pass the spot, they merge again into the flow of traffic.19

The closing frame segment solidifies the narrative’s image of social totality. By revealing that the pearl necklace was a worthless imitation, the newspaper article strengthens skepticism about existing social values and the protagonists’ decision to accept those values, join the quest for material wealth, and ultimately destroy their relationships. At the same time, images of the self-satisfied and dominating man, who directs the remorseful but submissive prostitute into the stream of anonymous pedestrians, reinforce the initial image of the street. According to the film’s narrative perspective, the street is a place where the rich and the poor coexist interdependently. It is a place where fast-paced, acquisitive modern society threatens what little compassion remains between human beings. It also is a place where those who would prefer to make an honest living and develop healthy interpersonal relationships often are forced to adopt cold and calculating methods of survival.

Beyond the Street had its premiere on 10 October 1929, in Berlin’s Atrium Theater. The mainstream reviews were very positive (see, for example, “Prometheus Erfolg,” Film-Kurier, 11 October 1929). The Communist newspapers also responded enthusiastically. Instead of drawing attention to the film’s subtle social criticism and rejecting the conclusion for being too pessimistic, reviews in Die Welt am Abend and Berlin am Morgen contrasted the film with previous street films and emphasized its higher artistic quality and realistic portrayal of the working-class environment. Despite the positive press response, Beyond the Street was unable to generate as much profit as did Storm over Asia and The Living Corpse.

There were two major reasons for its lack of success. First, during the final months of 1929, as the economic crisis deepened, the German public spent less on entertainment, and as the transition to sound film progressed, the popularity of silent films gradually decreased. Second, the cost of production made it difficult for Prometheus to realize a substantial profit with Beyond the Street. According to Willi Döll, Tuscherer mismanaged the film’s production.20 Although the team finished much of Beyond the Street in the Jofa studios in Johannisthal near Berlin, Tuscherer also organized a filming expedition in Holland. There the Prometheus crew, including the cameraman Friedl Behn-Grund, collected documentary footage of harbor scenes and expended 30,000 marks. Tuscherer sacrificed another 30,000 marks to attract Lissi Arna and, Döll claims, retained 3,000 marks for himself. The remaining production required an additional 30,000 marks. For a small company like Prometheus with only a limited reputation (and budget), Tuscherer’s expenditures were very high. As a result of his mismanagement, Prometheus replaced Tuscherer in September 1929. Juri Spielmann, whom Doll described as an indecisive party functionary, assumed the production manager’s position, and following the premiere of Beyond the Street, Prometheus concentrated on its next film, Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness.

MOTHER KRAUSE’s JOURNEY TO HAPPINESS

During the production of Beyond the Street, one of Berlin’s most popular artists, Heinrich Zille, died. Zille had attracted broad public interest with his sketches of working-class people and their environment beginning at the turn of the century. By 1925 his work was so popular that commercial filmmakers had begun to produce “Zilie” films, including The Notorious and The Illegitimate. The portrayal of the working class and its environment in these films for the most part resembled that of the street in films such as The Street and Tragedy of a Prostitute (see Chapter 8). The Zilie films characterized most inhabitants of the proletarian sphere as inherently bad, while suggesting that upper-class individuals were compassionate and philanthropic.

The Zilie films stimulated at least as much criticism as the street films among the German left. Leftist cultural activists rejected them; they claimed that producers used the artist’s name to maximize profit by suggesting that Heinrich Zille, whom the working class accepted as a trustworthy and sympathetic artist, endorsed or was in some way associated with them. When Zilie died, some of his friends, including Otto Nagel, Hans Baluschek, and Käthe Kollwitz, encouraged Prometheus to challenge the ideological orientation of the commercial films with a true Zilie film in commemoration of the artist.

Prometheus agreed and assembled a production team that consisted to a large extent of those who had produced Beyond the Street. The Fethke-Döll team provided a script, Robert Scharfenberg and Karl Haacker designed the sets, and Friedrich Gnass, the drunken sailor in Beyond the Street, played Max, a class-conscious worker. Only Mittler left the team. Phil Jutzi, who had worked extensively as a documentarist for Weltfilm and assisted cameraman A. Golovnja in The Living Corpse, took his place and functioned both as director and cameraman.

Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness portrays the plight of a proletarian mother and her two children.21 Mother Krause’s newspaper route and the rent collected from a man and his prostitute-girlfriend, who occupy one room of their apartment, provide the family’s only source of income. A crisis develops when the son, Paul, squanders the money he has collected for newspapers on beer. He leaves the family virtually penniless and forces each member to consider alternate methods for raising the employer’s 20 marks. Numerous possible solutions emerge. Mother Krause tries to borrow the money, but none of the well-dressed men she contacts is willing to help her. Paul resorts to burglary, shoots at a pawnbroker in panic, and eventually surrenders to the police. Erna, Paul’s sister, attempts prostitution. The middle-class man she solicits disgusts her, and she runs to her Marxist boyfriend, Max, who is participating in a demonstration. Erna joins him and later learns that he will provide the necessary money. Before the good news reaches Mother Krause, she becomes distraught and commits suicide. Max and Erna return too late to rescue her, and the film concludes with a flashback of the couple marching together in the demonstration.

Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness: Illustrierter Film-Kurier program cover. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

In many ways the production of Beyond the Street served as a model for the makers of Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness. Once again their intention was to convince audiences that the cinematic fiction was both authentic and typical. In contrast to the production of Beyond the Street, the Prometheus team also strove to minimize expenditures. For both reasons they engaged less well known stage players and relatively inexperienced film actors. In addition, Otto Nagel searched for and hired authentic Zilie types to play minor roles. While Nagel looked for typical characters, Scharfenberg and Haacker walked through the working-class community Berlin-Wedding to find representative settings. At the same time, Jutzi, guided by the Fethke-Döll script, constructed a cohesive narrative, integrating documentary footage with staged scenes in natural settings and scenes filmed in the Berlin Jofa studios.

Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness: advertisement materials include posters by Käthe Kollwitz and Otto Nagel. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

The exposition of Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness clearly illustrates the resulting effect. The film begins with a handwritten text, describing Berlin-Wedding as the home of enslaved workers, the poor, playful children, invalids, drunks, beggars, and prostitutes. The text is signed “Heinrich Zille” and followed by documentary shots that visually introduce the working-class environment. Individual segments of Zille’s text interrupt the sequence, suggesting that the documentary footage portrays what Zilie has described. Throughout the sequence a tracking and panning camera maintains the eye-level perspective of an observer, allowing spectators to imagine themselves moving within the milieu. The association between what the text describes and its visual representation invites the audience to ascribe the same degree of authenticity and typicality to the filmic portrayal as they do to Heinrich Zille’s artworks.

Omniscient intertitles replace Zille’s text and accompany a series of sequences; together they introduce Mother Krause and her family. Following the final text segment, the camera tracks from the street level over a narrow, enclosed tenement yard up to the window of an apartment. An intertitle explains that it is Mother Krause’s apartment. The camera tracks into the apartment and stops with a medium shot of a dancing couple. After another intertitle, introducing the dancers as Mother Krause’s daughter, Erna, and a boarder, a second sequence juxtaposes the dancing couple and people in the tenement yard. An association between the scene in the yard and the scene in the apartment begins with the connection between an organ-grinder, who entertains the people in the yard, and the dancers. The montage suggests that Erna and the boarder are dancing to the music in the yard, and the juxtaposition of women dancing below and the couple dancing in the apartment reinforces the association. When the boarder draws Erna closer and grabs her breast, she pushes him away and becomes visibly upset. Before her emotional response ends, the perspective shifts to the yard. There the organ-grinder’s monkey, who wears a hat similar to Erna’s, just behaves as Erna did in the previous shot. When Mother Krause scolds Erna’s frivolity, she does so in Berlin dialect, and a cut to the yard shifts attention to a close-up of a crying child.

With a variety of signifiers—the Zilie description, dialogue intertitles in Berlin dialect, montage juxtaposition—the narrative establishes a strong connection between the individual working-class family and what it portrays as an authentic working-class milieu. Throughout the exposition the narrative style resembles that of the frame segment in Beyond the Street; however, as the plot unfolds, a major difference emerges.

Although the working-class environments of Beyond the Street and Mother Krause’s journey to Happiness include similar lumpen-proletarian as well as proletarian types, their narratives organize them differently. Whereas the story of the beggar, unemployed young man, and prostitute progresses in a relatively straightforward sequential manner, the story of Mother Krause, her children, the proletarian Max, and the lumpen-proletarian boarder unfolds much more hypotactically, with frequent parallel montage sequences. Some sequences contrast the methods used by Mother Krause, Paul, and Erna to collect the money they need; others contrast Max and the boarder as they interact with Erna. In the process, the narrative encourages the audience to sympathize with Erna in her developing relationship to Max and ultimately to affirm their political solution to the family’s problems. The scenes in which Erna turns to Max for help, Paul burglarizes a pawnshop with the lumpen-proletarian boarder, and Mother Krause commits suicide exemplify the narrative thrust.

Initially Erna and Paul accept the boarder’s schemes to collect money. He proposes burglary to Paul and prostitution to Erna. After her well-dressed, overweight bourgeois client attacks her in his apartment, she flees. The spectator next sees Erna running to Max’s apartment, where she learns that he is at a demonstration. Erna leaves the apartment slowly and stops twice. A close-up of her facial expression indicates that she has made a decision. She no longer hesitates. The narrative perspective moves with Erna, allowing spectators to imagine her perspective while following behind her. In the next scene the perspective shifts from long shots of Erna and the demonstrators walking in opposite directions to medium shots of the demonstrators marching toward what the spectator imagines to be Erna’s position. In the background a sign demands: “Working women join the ranks!” Before Erna joins the demonstrators, the narrative perspective does. The spectator now observes Erna from within the ranks of the demonstrators as she continues to look for Max. Occasionally the perspective merges with hers, shifting from shoes of individual demonstrators to shots of their marching feet. Eventually, Erna recognizes something and begins to walk with the marchers. The narrative perspective again moves with her as she joins Max in the demonstration. The view now moves from their feet, which begin to march together, back to their smiling faces.

The scene encourages working-class audiences to identify with Erna as she joins the demonstration. The exposition earlier suggested that she and her family are typical representatives of the working class. Here Erna represents all working-class women whom the sign orders to “join the ranks.” By staging the demonstration in the streets of Berlin and including hundreds of real workers, the filmmakers strengthen the association between working-class filmgoers, Erna, and the demonstrators. But the most effective technique is the use of photography and montage. With it the Prometheus team simultaneously conveys the dynamic quality of the demonstration and draws the audience and Erna into it.

The juxtaposition of segments following the demonstration further motivates identification with Erna. In the first scene Max and Erna decide to attend a workers’ festival. Some workers remind Mother Krause of her woes by singing, “We will drink granny’s little house away.” She leaves, and when Max asks for an explanation, Erna describes the family’s problems. Max immediately offers assistance. As the festival progresses, parallel montage sequences depict Paul and the unfolding burglary. When Max offers to help Erna, the sequence shifts again to the pawnshop, then repeatedly from the burglary to the apartment where Mother Krause worries. The audience, which knows that Max will help, must watch with increasing dismay, while the police arrest Paul, and Mother Krause commits suicide. The narrative’s order of events urges perception of Paul’s and Mother Krause’s behavior as both futile and unnecessary, thus strengthening identification with Erna.

The narrative style employed by the producers of Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness enabled them to present a more differentiated image of the working-class milieu than appeared in the commercial street films, Zilie films, or even in Beyond the Street. It distinguished between an older generation (Mother Krause), whose members accepted existing social values and blamed themselves for unemployment and poverty, and a younger, less fatalistic generation. It also distinguished between lumpen-proletarians (the boarder and Paul), whose rejection of social values manifested itself in criminal action, and the proletarians (Max and Erna) who demanded social change.22 While positing their more differentiated image, the producers asserted an even greater claim to authenticity and associated the audience’s perspective with that of fictional protagonists more intensely than Gerhard Lamprecht or Leo Mittler had done.

Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness had its premiere on 30 December 1929 in Berlin’s Alhambra Theater. Although some critics characterized the film as agitational (8-Uhr Abendblatt, 31 December 1929), most trade journals and newspapers recommended it enthusiastically. The IAH newspapers were especially positive in their reviews, focusing specifically on the film’s realistic portrayal and its emotional appeal. Even Alfred Durus found little to criticize (Die Rote Fahne, 1 January 1930). Durus outlined the differences between Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness and earlier Prometheus films, emphasizing its authenticity and revolutionary quality. For him, the choice of Berlin-Wedding as the center of production and the narrative differentiation between the criminal lumpen proletarians and the class-conscious proletarians made it a much better film than Beyond the Street. Its only weakness, in Durus’s estimation, was the somewhat indirect and symbolic, instead of concrete, reference to the social causes for the family’s plight.

During its first week in the Berlin theaters, the producers of another film, Zwischen Spree und Tanke (Between the Spree and Tanke), claimed that their film was the true Zilie film and filed a protest against Prometheus for plagiarism (see “Polizei und Gerichte um den Zille-Film”— “Police and Courts on the Zille Film,” L.B.B., 8 January 1929). The first regional court in Berlin rejected the complaint, and the film began an extremely successful run in theaters all over Germany. According to a poll of 1,138 theaters taken by Film-Kurier (31 May 1930), it was the 24th most popular film in Germany of 1930.

THE DISSOLUTION OF PROMETHEUS AND KUHLE WAMPE

As the transition to sound progressed and the economic crisis intensified, Prometheus found it increasingly difficult to sustain itself. In 1930 the company produced only six short travelogues from documentary footage collected in Rotterdam, but it continued to distribute Soviet feature films, including Das Lied vom alten Markt (The Song of the Old Market), Der Mann, der sein Gedächtnis verlor (The Man Who Lost His Memory), Der blaue Expreß (The Blue Express), and Igdenbu, der große Jäger (Igdenbu, the Great Hunter).23 Prometheus also tried to remain competitive by producing a sound version of Battleship Potemkin and by distributing an inexpensive sound film about bicycle racing, Rivalen im Weltrekord (Rivals for the World Record).

Each of the Soviet films received generally positive reviews, but none was successful enough to enable Prometheus to initiate its own sound film production. It is also likely that Münzenburg, the IAH, and the Soviet film industry were unwilling to invest in Prometheus significantly at a time when the Comintern and the KPD hoped that revolutionary political activity would render cultural activity temporarily superfluous. In 1931 distribution continued to be the company’s primary activity. Three Soviet films, Dovschenko’s Erde (Earth), Feuertransport (Fire Transport), and the first Soviet sound film, The Way into Life, attracted large audiences.24 Despite the relative popularity of the films, theater owners offered very little for the right to screen them.25 Most owners booked Prometheus films, if at all, for two- or three-day periods and paid from one hundred to three hundred marks. At the same time National Socialist organizations began a boycott of all films they considered to be Bolshevist. The previously tolerant creditors withheld further support for Prometheus, and the company suspended payments at the end of 1931. In February of 1932, following a court settlement, Prometheus formally dissolved.26

The Way into Life: Prometheus distributes first Soviet sound film in Germany, Illustrierter Film-Kurier program cover. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

As late as 1931 Prometheus announced plans for production, including a sound film comedy to be directed by Phil Jutzi and an adaptation of Emile Zola’s Germinal. The company produced neither film but did assist in the first phase of another project. Following his work on How the Worker Lives, Slatan Dudow developed a plan to produce a sound feature with little or no money.27 Bertolt Brecht decided to accept Dudow’s proposal for enlisting the help of the Communist-led Fichte Sport Club. The club members responded enthusiastically, gathering over four thousand members from other sports clubs to participate in what was the German left’s first sound feature and its last major film before Hitler assumed power in 1933. The film was Kuhle Wampe.

The interaction between Dudow, Brecht, and the Fichte Sport Club characterized the film’s production. In addition to budgetary constraints, the radically democratic aesthetic models developed by Brecht and his colleagues significantly influenced work on Kuhle Wampe. By 1931 Brecht had formulated his LehrStücktheorie and had completed a number of Lehrstück experiments.28 With his new plays Brecht strove to increase the participation of players as well as audiences in production, to disrupt the dramatic illusion of reality, to encourage emotionally engaged and intellectually critical reception, and to orient reception toward reflection about the relationship between dramatic fiction and everyday life. Following an enthusiastic collaboration with Berlin’s Karl-Marx-Schule in rehearsing, performing, and reworking the Jasager material in 1930, Brecht was ready to undertake a similar experiment with film.

As the project developed, Hanns Eisler, who was the leading KPD proponent of a radically democratic alternative to traditional forms of artistic production and reception, joined the collective and began composing music for the film. Once Brecht and Dudow had produced an exposé, Ernst Ottwalt, a member of the BPRS who had developed a narrative style similar to that of Brecht’s epic theater, stepped in and assisted in completing the final script.29 Prometheus provided its set designers, Scharfenberg and Haacker. In August 1931 Günter Krampf replaced Weizenberg, a cameraman whom the collective had perceived to be unwilling to adopt its aesthetic orientation. Members from leftist theater groups, including the Gruppe junger Schauspieler, and agitprop groups such as Das rote Sprachrohr played leading roles in the film, in addition to the volunteers from the various sports organizations. According to Brecht, as the collective grew, the interaction of its members became at least as important as the product of their efforts.30

Interruptions slowed the production of Kuhle Wampe, which lasted over a year. The producers periodically exhausted their operating capital, and their creditors occasionally threatened to withdraw support.31 Filming began in August 1931, and after Prometheus dissolved in February 1932, the Prasens film company, with the financial backing of Lazar Wechsler, purchased the rights to Kuhle Wampe and finished production in March 1932. Prasens also submitted the film to the censors, who rejected it twice before accepting a substantially edited version at the end of April. Finally, on 30 May 1932, Kuhle Wampe had its premiere in Berlin’s Atrium Theater.

The opening sequences of Kuhle Wampe depict unemployed workers racing on bicycles through the streets of Berlin in a futile search for work. One of them, the young Franz Bönicke, has been unemployed for six months. When he returns to his home for dinner, Franz learns that his unemployment compensation has expired, and his parents scold him. His sister Anni suggests that there are social causes for the family’s predicament, but Father Bönicke continues to blame his son. In desperation the son commits suicide. In the aftermath of the suicide Anni asks the landlord and various welfare agencies for assistance with the family’s rent payments. No one is willing to help, and a judge finally evicts them. Anni’s boyfriend, Fritz, suggests that the family move to Kuhle Wampe, a large tent colony outside Berlin. There Anni becomes pregnant. Her father demands that she marry Fritz and arranges an engagement party. At the celebration Fritz reveals that he feels trapped by the marriage. Anni responds by breaking the engagement and moving in with her friend, Gerda. Anni also returns to her sports club where fellow members collect the money she needs for an abortion. Fritz, who in the meantime has lost his job, searches for and finds Anni with her friends at the sports club. He joins them in preparing for a festival, during which the participants interact and discuss politics. Anni races with her rowing team; she and Fritz join others in singing Eisler’s song of solidarity; and everyone listens as an agitprop group depicts a family whose members deny a landlord the right to evict them. While returning home from the festival on the S-Bahn, some of the participants argue with a businessman who is indifferent toward farmers who burn coffee bean crops to inflate prices. The workers condemn the practice and ask the man, who will change the system? The film ends when they assert that the dissatisfied will change it.