THE FORGOTTEN STORY

At the end of 1925 a small film company emerged in Berlin to distribute a Soviet film that had failed to attract widespread acclaim in the Soviet Union. When German censors decided to forbid public screenings of the film early in 1926, a major controversy erupted, and interest in the film increased. The government finally acquiesced in the face of mass opposition to its decision, and the film premiered in Berlin’s Apollo Theater on 29 April 1926. The executives of the film’s fledgling distributor convinced two internationally famous film stars to attend the premiere, they and the critics raved about the film, and it ultimately became one of the best-known films in the history of cinema.

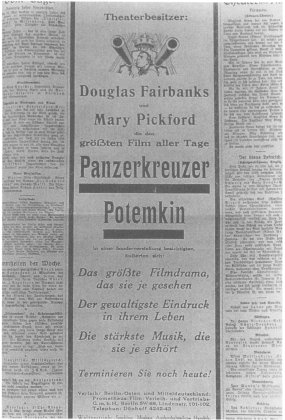

The film was Sergei Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin, and the visiting film stars were Mary Pickford and Douglas Fairbanks—but who remembers the names of the film company or its executives? Why did the company work so hard to distribute a film that had failed to win acclaim in its domestic market? And what other projects did the company undertake following its unprecedented success with Potemkin?

Later in 1926, the same film company began the production of what it hoped would be a second commercial blockbuster. The script was based on a selection of short stories by Anton Chekov. Another Russian, Alexander Rasumny, agreed to direct the film. The company also engaged a number of stars to appear in major roles. They included, among others, Heinrich George, Werner Krauss, and Fritz Kampers. The film premiered in one of Berlin’s largest movie houses, the Capitol Theater, on 2 November 1926. Its production values should have attracted national, if not international, attention—but who can recall the film? Was this second film as successful as the first? How did the company then proceed?

Battleship Potemkin: Douglas Fairbanks and Mary Pickford praise the film in the Film-Kurier, 7 May 1926. (Staatliches Filmarchiv der DDR)

The film’s title was Überflüssige Menschen (literally, Superfluous People), and it was the first of many films that the tiny Prometheus Film-Verleih und Vertriebs-GmbH (Prometheus) produced and distributed commercially in Germany between 1926 and 1931. The initial Prometheus film failed to excite critics and audiences, but subsequent films did attract substantial critical acclaim. They included Eins + Eins = Drei (One + One = Three, 1927), Schinderhannes, der Rebell vom Rhein (Schinderhannes, the Rebel of the Rhine, 1927–28), Der lebende Leichnam (The Living Corpse, 1928), Jenseits der Straße (Beyond the Street, 1929), Mutter Krausens Fahrt ins Glück (Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness, 1929), and Kuhle Wampe oder Wem gehört die Welt? (Kuhle Wampe or to Whom Does the World Belong? 1931–32).

Willi Münzenberg, the leader of the Internationale Arbeiterhilfe (International Workers’ Relief, IAH) and an extremely talented media man, played a central role in bringing Potemkin to Berlin and in organizing Prometheus. He and his associates worked fervently throughout the Weimar era to create an alternative to the dominant sources of news and entertainment, to inform Germans about the cultural changes in the Soviet Union, and to nurture the development of a proletarian culture in Germany. With Prometheus, Münzenberg hoped to challenge what he perceived as the conservative to reactionary ideological influence of mainstream commercial cinema. The German Communist party, as well as a large number of well-known intellectuals and artists, supported him. The list of individuals who contributed to Prometheus endeavors included Béla Balázs, Kurt Bernhardt, Bertolt Brecht, Slatan Dudow, Hanns Eisler, Käthe Kollwitz, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and Carl Zuckmayer.

Among the ranks of Prometheus co-workers were filmmakers who also figured prominently in the production of what have become German film classics. The director of One + One = Three, Béla Balázs, was one of the scriptwriters for The Threepenny Opera (1931). The scriptwriter for Schinderhannes, Carl Zuckmayer, was also a scriptwriter for The Blue Angel (1930). Phil Jutzi directed both Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness and Berlin Alexanderplatz (1931). Prometheus actors, cameramen, and set designers also joined the production teams of these and many other well-known German films.

In addition to Prometheus and its filmmakers, other leftist organizations and individuals contributed measurably to the development of German cinema during the second half of the 1920s. While the German Communists supported the production of Prometheus and created the Film-Kartell “Welt-Film” GmbH (Weltfilm) to coordinate film events for Communist party meetings, membership drives, and campaign programs, the Social Democratic party (SPD) supported the production of a few commercial films and operated its own Film und Lichtbilddienst (FuL) to coordinate SPD film activities. At about the same time, a nonpartisan national consumers’ organization, the Volksfilmverband (VFV), emerged with prominent board members, including Leonhard Frank, Leo Lania, G. W. Pabst, and Erwin Piscator; its president was Heinrich Mann.

The VFV, too, set out to create an independent alternative to mainstream commercial cinema, complete with its own production, distribution, and screening network. The organization contributed to the production of one independent feature film and a number of documentaries. It also published a journal, Film und Volk, conducted public seminars on the status and potential of cinema, and developed a national system of film clubs that coordinated their own noncommercial film events. Other independent leftists imitated the efforts of the VFV. They published impressive critiques in newspapers, journals, and books, formulated manifestos for new movements in cinema, and worked within the developing institution of cinema to influence its contours.

Although various leftist individuals and groups influenced significantly the development of German cinema in the Weimar Republic, their story has for the most part been forgotten. Popular accounts of German film history, especially those of West German film historians, have included numerous retrospectives of the “Golden Years” of Weimar’s mainstream cinema and imply that postwar Germany should strive to regain the glamour and glory of those years.1 Those that do include information about the film activity of the German left refer only tangentially to films such as Mother Krause’s Journey to Happiness and Kuhle Wampe, characterizing them more as curious anomalies.2 Rarely do the films of the left appear as expressions of campaigns to compete commercially and ideologically with mainstream cinema.

POSTWAR ACCOUNTS OF WEIMAR CINEMA

The attempt to explain the lack of attention to this chapter in German film history begins in the immediate post-World War II period. After the fall of the Third Reich, the German people began the tedious process of reconstruction. For most, the primary tasks during the first years were to find adequate shelter, guarantee an ample supply of food, and begin clearing away the mountains of rubble. There was little time and perhaps even less energy available for a critical review of the cultural heritage.

When in the 1950s Germans did find the time and energy for fulfilling additional needs, the desire for commercial entertainment in the West and the exigencies of Stalinist rule in the East set the standards for film production and reception. In the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG) most filmmakers followed the Ufa tradition and competed with Hollywood for control of the West German market.3 In the German Democratic Republic (GDR) many filmmakers who had learned their trade in Nazi Germany combined that experience with the guidelines of socialist realism to produce their films.4 The film activity of the German left during the Weimar Republic had little influence on filmmaking in the immediate postwar era. Evidence of that activity either disappeared or gathered dust on the shelves of archives.

As reconstruction progressed, historians and sociologists began sifting through the vast intellectual rubble of the German past in search of what could be used to build and sustain a new democratic Germany. For film historians the project included a review of German cinema, from its birth to its development as an institution and its transformation into a medium for promoting and reinforcing National Socialist ideology. Some of the earliest studies became standard works of German film history, but the investigation has continued to the present.

The most frequently cited work of Siegfried Kracauer emphasized the commercial and collective quality of cinema in the Weimar Republic.5 Kracauer argued that the dominant characteristics of Weimar cinema motivated filmmakers to appeal to the interests of Germany’s largest social group, the petty bourgeoisie, and, in the process, to reflect that group’s psychological composition. According to his perspective, the analysis of Weimar cinema could reveal important insights about the shared psychological dispositions that nurtured National Socialism. Consequently, he scrutinized what he considered the most significant commercial German films with great care and tended to deemphasize all other films, including those of the German left.

In their effort to demonstrate continuity between the capitalist cinema of the Weimar era, the cinema of the Third Reich, and postwar West German cinema, film historians of the GDR generally have employed Lenin’s theory of two cultures to portray the history of Weimar cinema.6 They often divide Weimar film production into corresponding categories: films of the bourgeois “dream factory,” which serve a capitalist elite in its campaign to pacify a dissatisfied working class, and films of an emerging proletarian culture.7 To be sure, East German scholars have paid some attention to the experiments of the German left during the Weimar era, but their studies often suggest a too simplistic image of powerful conservative and reactionary filmmakers who schemed to influence public opinion while stifling the German left’s efforts to offer an alternative.8 Their accounts of the overwhelming power of the largest commercial producers and the praiseworthy attempts of the Communist left to challenge mainstream cinema generally have paid inadequate attention both to the emerging institutional factors that inhibited experimentation and the mistakes of the German left.

Some of the younger West German film historians of the 1970s, similar to those in the GDR, perceived film as a medium that could be used by opposing interest groups to influence public opinion.9 In contrast to all other historians of Weimar film, they concentrated almost exclusively on various aspects of the German left’s activity in the Weimar Republic. In the majority of cases their intention was to learn from the past what would be necessary to develop a radically new approach to the film medium as an ideologically progressive alternative to the dominant “culture industry” of the West and the relatively orthodox Marxist models of the East. Although some of their studies provided more critical and differentiated accounts of the German left’s film activity in the Weimar Republic, their interest waned as the student movement dissolved, and the story has remained incomplete.

FILM AS COMMODITY AND THE MARGINALITY OF LEFTIST EXPERIMENTS

Attempts to explain the lack of attention to the film activity of the German left in the Weimar Republic also require acknowledgment of its marginality. Despite the fact that talented and well-known personalities contributed to the work of Prometheus, the FuL, the VFV, and other projects, they never mounted a serious challenge to mainstream cinema. Kracauer is correct when he claims that it was Hollywood and Ufa’s Babelsberg that attracted the interest of the German public in the 1920s. Their films filled the theaters and their advertisements occupied the front pages of the leading trade magazines. But is it also correct that either the psychological dispositions of the petty bourgeoisie or the “scheming” of capitalist producers in mainstream cinema alone squelched the opportunity for a leftist alternative?

As the preceding survey indicates, many possibilities remain for continuing, expanding, and further differentiating the search for information about the relationship between cinema and social development in the Weimar Republic. This study contributes to the process. By reviewing the emergence of a cinematic institution in Germany between 1918 and 1933 (focusing above all on German films and film journalism), it attempts to pinpoint the factors that determined commercial cinema’s quality. It outlines the relationship between commercial film production and reception and considers the influence of that relationship on the social structures that generate ideological standpoints, as well as ideological content. It also provides a context for the primary topic of investigation: the efforts of various groups within the German left to compete ideologically with mainstream cinema by producing commercial films and establishing noncommercial alternatives.10

At approximately the same time Kracauer’s work appeared, Swiss sociologist Peter Bächlin completed his study of film’s status as a commodity. Bächlin, like Kracauer, asserted the primacy of economic factors for the quality of film production and the relationship between production and reception (11–18). Both argued that the profit motive significantly influences the selection of subjects for production, the manner in which the subjects are treated, and ultimately the quality of interaction between filmmakers, films, and film audiences. But Bächlin outlined the development of mainstream cinema in greater detail than Kracauer and provided a wealth of empirical evidence to support his claims. In contrast to Kracauer, who relied to a large extent on personal experience and the film libraries at the Museum of Modern Art and Library of Congress, Bächlin based his work more on sociological studies and the statistical reports compiled by the film industry.

According to Bächlin, commercial filmmakers produce commodities to create an exchange value. To increase the exchange value of their commodities, they strive to minimize production costs and maximize the use value for the film audience. He suggests that entertainment is the fundamental use value of commercial cinema (162).

The commodity character of commercial cinema has nurtured what Bächlin refers to as the standardization of film production (164). As early as the first decade of the twentieth century, filmmakers in Europe and in the United States realized that one of the easiest and most reliable methods for minimizing production costs and maximizing the probability of box-office success was to measure the commercial strength of earlier films and to imitate them. Producers measured the success of specific plots and subject matter, then determined which actors appealed most, engaged them with large salaries, and marketed them as stars. The result was the establishment of popular film genres and the birth of the star system. The same considerations influenced the selection of literary models, directors, and other crew members.

Bächlin discovered that as filmmakers refined and expanded their techniques for standardizing production, the degree of artistic cooperation and experimentation decreased. More democratic, heterogeneous, and spontaneous elements gave way to autocratic, homogeneous, and extremely well-calculated forms of production. By relying on a relatively small group of established filmmakers, film companies restricted the number of people who could contribute significantly to the production process; independent contributions decreased as the process of standardization continued. In addition to regulating the degree of deviation from proven plotlines and subjects, companies developed libraries of typical scenes that could be edited into a film and constructed interchangeable backdrops to be used and reused. Production managers rigidly adhered to schedules, and this variety of factors made the production process far more autocratic than democratic, further inhibiting experimentation and creativity.

Of greater ideological significance for Bächlin was the commercial film industry’s emphasis on cinematic entertainment. He explained that while imitating with only minor deviations the plots of commercially successful films and marketing stars, producers developed additional strategies to ensure the broadest possible appeal for their films. Like Kracauer, he believed that producers concentrated on the entertainment needs of the largest social class—the petty bourgeoisie. He also argued that filmmakers did everything possible to avoid addressing social, political, religious, and other issues that might please one social group and disturb another (189–193). According to Bächlin, the desire of filmmakers to avoid controversy solidified and strengthened conservative social trends. Although he never precisely explained how the process functioned, one might infer that cinema does so simply by distracting attention from social issues, thus inhibiting the process of democratic social change.

It was not until the 1970s that Dieter Prokop, borrowing from the works of Theodor Adorno, Max Horkheimer, Herbert Marcuse, and Wilhelm Reich, outlined in much greater detail the quality of cinematic entertainment and its influence on the generation and maintenance of ideology within a specific sociohistorical context. Prokop proceeds from the premise that societies develop around strategies to fulfill the material and psychological needs of their members and that mass culture (including cinema) contributes to the establishment of the dominant strategies in modern Western societies (2).

Prokop’s first major claim about the ideological quality of film production is that it excludes the majority of society’s members from participating in the development of such strategies. Like Bächlin, Prokop asserts that economic considerations determine the quality of film production and reception (3). However, while affirming Kracauer’s focus on economic factors, Prokop restates and expands Bächlin’s challenge to claims about commercial film’s reflection of a collective mentality. He suggests that the desire to maximize profit bureaucratizes the process of production, privileging the positions of producers and production managers while minimizing spontaneous and cooperative artistic experimentation. According to Prokop, the number of people who contribute significantly to the process of production decreases further as the number of production companies decreases. His historical outline characterizes the quality of German cinema as monopolistic as early as 1930 (17).

The most provocative insights of Prokop’s work describe the relationship between cinematic entertainment and the regressive elements of the petty-bourgeois mentality (11–34). He maintains that although the overwhelming majority of people never participate directly in film production, the potential exists for everyone to participate in generating ideological standpoints as emotionally engaged and intellectually critical recipients of cinematic material. Yet, according to Prokop, existing cinematic institutions inhibit the critical participation of recipients. Like his predecessors, he asserts that the formula for commercial success motivates producers to focus selectively on the entertainment needs of the petty bourgeoisie. He continues, by citing Wilhelm Reich’s concept of a schizophrenic human psyche, claiming that individuals constantly vacillate between progressive and regressive positions and that cinematic entertainment reinforces the regressive positions (6, 27–34).

Prokop bases his explanation of cinematic entertainment’s quality on a variation of Freudian perceptions. Instead of referring to the id, ego, and superego, he posits an image of human beings as spontaneous producers of material and psychological needs that are modified, redirected, and/or suppressed by the principle of what is realistically achievable and socially acceptable. For the petty bourgeoisie, experiences at the workplace, in the world of commerce, and in other socializing institutions modify and suppress the need for spontaneity, innovation, productivity, and meaningful social interaction, translating these needs into the desire for competitive success, upward social mobility, consumerism, and security. As a result, the individual simultaneously yearns for freedom from the experience of monotony, subservience, and automation, while fearing the consequences of deviating from the norm, thus jeopardizing the opportunity for success and security.

According to Prokop, cinematic entertainment considers the conflict between the unreflected needs of the petty bourgeoisie and their perceived principles of reality and social acceptability. It responds to the regressive needs that emerge from the conflict. He argues that instead of providing spectators with an opportunity to contemplate the cinematic experience collectively in an effort to develop ideological strategies, commercial cinema encourages them, via emotional identification with fictional figures, to artificially satisfy and then reproduce regressive needs without threatening their integration within society (27–28). Whether filmmakers employ narrative techniques of cinematic realism or contrapuntal montage, by adhering to the formula for commercial success, they stimulate the development of autocratic structures for the generation of ideological viewpoints. They discourage individuals from participating cooperatively either in producing films or in considering their significance for the development and maintenance of the strategies they practice for social interaction.

Five fundamental claims about the relationship between film production and the production of ideology in modern Western societies emerge from Bächlin’s and Prokop’s work:

1. The quality of film production and distribution depends primarily on economic considerations;

2. Film production within monopolistic systems, or in systems with tendencies toward monopolization, stifles spontaneous, productive, and cooperative interaction;

3. Commercial cinematic entertainment responds to and, to a large extent, fosters the abstract, regressive needs of petty-bourgeois film spectators;

4. The aesthetic form of cinematic entertainment minimizes the possibility for critical and cooperative reception;

5. The potential for alternatives to established cinematic institutions remains limited as long as film retains its quality as a commodity.

This study analyzes to what degree these claims accurately describe the quality of the developing cinematic institution in Germany between 1918 and 1933. It attempts to answer the following questions: Did economic factors significantly influence the quality of film production? What other factors influenced production? Was the quality of film production experimental and cooperative or calculated and autocratic? Did commercial cinematic entertainment focus only on satisfying the regressive needs of the petty bourgeoisie? What were the dominant aesthetic forms of cinema, and how did they influence reception? What attempts were made to establish alternatives to mainstream cinema, and what factors determined the relative success and failures of such attempts? And how do the answers to these questions facilitate a better understanding of the film activity of the German left in the Weimar Republic? While presenting information and positing viewpoints, the study encourages further discussion about the relationship between cinema and social development in the Weimar Republic and in other modern Western cultures.