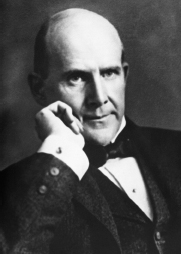

CREDIT: Associated Press

IN 1920, Eugene Victor Debs ran for president from a cell in the federal prison in Atlanta, Georgia, convicted for opposing World War I. Heading the Socialist Party ticket, Debs won nearly a million votes—3.5 percent of the popular vote—in a four-way race that also included the Democrats, Republicans, and Progressives. The vote was a tribute to Debs, a beloved figure in many parts of America, but it was also a reminder of the young country’s propensity for official repression when confronted with dissent and protest.

Debs was both a fierce patriot and a fiery radical. He came to his socialist politics gradually, even reluctantly. Perhaps because of this he could persuade and agitate audiences with his radical message, for he embodied the best of America’s ideals of justice, compassion, and fairness.

Debs looked like a bald Sunday School teacher, all six and a half feet of him, with a kind face and an aura of optimism and hope. His political and social views emerged from his Christian upbringing in the heartland of Indiana. He absorbed the small-town values of skilled workers striving to join the middle class and the virtues of hard work, frugality, and benevolence.

The son of Alsatian immigrant retail grocers, Debs was born and raised in Terre Haute, Indiana. As a youth, he loved reading the fiery speeches of dissidents like Patrick Henry and John Brown and soon began attending lectures by such well-known orators as James Whitcomb Riley, abolitionist Wendell Phillips, and suffragist Susan B. Anthony. He left school at fourteen to work as a paint scraper in the Terre Haute railroad yards. He quickly rose to a job as a locomotive fireman. He was laid off during the depression of 1873, found another job as a billing clerk for a grocery company, and never worked for a railroad company again. But he remained close to his railroad friends, who admired his leadership skills. When the Brotherhood of Locomotive Firemen (BLF) organized a chapter in Terre Haute in 1875, Debs signed up as a charter member and was elected recording secretary.

Debs originally viewed the BLF as a kind of charitable and fraternal organization, helping injured workers and, if necessary, their widows and children. He opposed strikes and the violence that often accompanied them, even though the police and company thugs often caused the violence. After the railroad strike of 1877—the first truly national strike in US history, which ended in defeat for the unions after heavy government repression—Debs gave a speech defending the union from charges, widespread in the press, that it had encouraged violence. Debs got a rousing reception and was soon named grand secretary of the national union and editor of its magazine. Under Debs’s editorship, the magazine became a leading labor voice, its readership expanding far beyond BLF members.

In addition to this union job, Debs embarked on a political career. He served two terms as city clerk of Terre Haute and was elected to the Indiana State Assembly in 1884, but after one term he decided that the labor movement was a better way to achieve his reformist goals. He still believed in the possibility of industrial cooperation and discouraged workers from participating in confrontations with employers or the government.

In the mid-1880s, the railroad companies—which had once provided well-paying jobs to their skilled workers—began reclassifying occupations and cutting wages. This led to a series of major strikes, each of which was crushed by the railroad companies. The companies hired private thugs to use violence against strikers and pitted the different railroad brotherhoods against each other, hiring scab employees from different trades to replace the strikers.

These events shook Debs’s thinking. As late as 1886, Debs, along with other railroad brotherhood officials, refused to support the Knights of Labor strike against Jay Gould’s railroad company. When the fledgling American Federation of Labor that year led a national general strike for the eight-hour workday, Debs was silent. But with this new strike wave, Debs began to question whether big corporations could ever be trusted to work cooperatively with workers or to support political democracy.

In 1891, realizing that railroad workers were easily divided and could not prevail against the growing economic and political power of the corporations, Debs left the BLF. He saw the need for an industry-wide union organization that would unite all railroad workers. His guiding principle became the Knights of Labor slogan: “An injury to one is the concern of all.” In 1893, Debs brought together union leaders from the different crafts at a meeting in Chicago and founded the American Railway Union (ARU).

The ARU’s membership grew quickly. It was the first large national industrial union, a forerunner of the great industrial unions that emerged in the 1930s, and it won its first major test. In response to a strike, the Great Northern Railroad in 1893 capitulated to almost all the union’s demands.

The next year, the Pullman Company laid off workers and cut wages but did not lower rent in the company-owned houses or prices for groceries at the company store where workers were required to shop. Workers from Pullman asked the ARU for support. Some Chicago civic leaders, including Jane Addams, tried to arrange behind-the-scenes diplomacy to settle the strike, but Pullman refused to negotiate. So Debs and the ARU called for a national boycott (or a “sympathy strike”) of Pullman cars. The ARU’s 150,000 members in over twenty states refused to work on trains pulling the cars. They went on strike, not to win any demands of their own but to help several thousand Pullman workers win their strike. But the railroads found a sympathetic judge who ruled that the boycott was interfering with the US mail and issued an injunction to end the boycott. The ARU refused to desist, so President Grover Cleveland—a Democrat and a foe of the labor movement—sent in federal troops. ARU leaders, including Debs, were arrested on conspiracy charges. Debs and his union compatriots were sentenced to six-month jail terms for disregarding the injunction.

Debs used his six months in prison to think about what had gone wrong with his union organizing. He decided that the collusion between the ever-larger corporations and the federal government, including the courts and the National Guard, could not be undone by union activism alone. Redeeming American democracy from its corporate stranglehold required political action. Because both Republican and Democratic presidents called in troops to stop working-class victories, Debs was convinced that America needed a new political party, one whose base would be made up of workers and their unions.

Milwaukee’s Socialist leader Victor Berger visited Debs in jail, bringing a copy of Karl Marx’s Das Kapital. Debs read it carefully and began to consider the potential of socialism as an alternative to capitalism. After his release, he traveled to Chicago by train, and was astonished to see a crowd of over 100,000 people gathered in the pouring rain to greet him.

Debs helped organize the Social Democratic Party, a new party modeled on similar growing mass organizations in Europe. He ran for president on the party’s ticket in 1900 and received 88,000 votes. The next year, the Social Democrats merged with some members of the Socialist Labor Party to form the Socialist Party of America. Debs ran again for president in 1904, this time attracting 400,000 votes. In 1905, he joined with other union activists and radicals to start the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the “Wobblies,” as they were known. But although he and the Wobblies shared a belief in organizing all workers into “one big union,” Debs did not share their opposition to political action, to running candidates for office. The IWW favored what they called “direct action” instead, including seizing direct control of industry through mass strikes.

Debs resigned from the IWW in 1908 and ran for president a third time, doing no better than in 1904. But by 1910, America’s mood was changing. Dozens of Socialists won victories in local and state races for office, advancing a specific agenda of radical reforms, including women’s right to vote, child labor laws, and workers’ rights to join unions and when necessary to strike, as well as workplace safety laws for workers in railroads, mines, and factories. Two years later, they expanded their victories, and Debs polled nearly 1 million votes for president. He would have garnered more votes, but two other candidates—Democrat Woodrow Wilson and Progressive Party candidate (and former president) Theodore Roosevelt—stole some of the Socialists’ thunder, diverting the votes of workers, women, and consumers with promises of such “progressive” reforms as women’s suffrage, child labor laws, and workers’ right to organize unions. One cartoonist drew a picture of Debs skinny-dipping while Teddy Roosevelt made off with his clothes.

Debs was a tireless campaigner but could not expect sympathetic coverage in the mainstream press. The socialist newspapers—the Appeal to Reason in the Midwest and the Jewish Daily Forward in New York, in particular—covered his campaign and had large readerships. Still, Debs had to travel to get the word out, taking trains from city to city, speaking wherever a crowd could be assembled. Without microphones, Debs had to speak loudly and dramatically; his words rippled through the crowd as people relayed the speech to one another.

Despite Debs’s defeat in 1912, he won over 10 percent of the vote in Arizona, California, Idaho, Montana, Nevada, Oklahoma, Oregon, and Washington State. His campaign helped fellow Socialists win elections throughout the country. That year, about 1,200 Socialist Party members held public office in 340 cities, including seventy-nine mayors in cities including Milwaukee, Buffalo, Minneapolis, Reading, and Schenectady.

In 1917, President Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany and its allies. That move catalyzed widespread opposition from within the Senate (led by Robert M. La Follette) and by civil libertarians, religious pacifists, and Socialists, led by Debs. Congress passed the Espionage Act, which made it illegal to incite active opposition to US involvement in the war. Federal agents arrested scores of Socialists, Wobblies, and other dissidents. Though ill, Debs delivered a series of antiwar speeches; he was arrested, charged with impeding the war effort, convicted, and sentenced to ten years in federal prison.

On September 18, Debs delivered his most famous speech in a Cleveland federal courtroom upon being sentenced to prison. His opening remarks remain some of the most moving words in American history:

Your Honor, years ago I recognized my kinship with all living beings, and I made up my mind that I was not one bit better than the meanest on earth. I said then, and I say now, that while there is a lower class, I am in it, and while there is a criminal element I am of it, and while there is a soul in prison, I am not free.

I listened to all that was said in this court in support and justification of this prosecution, but my mind remains unchanged. I look upon the Espionage Law as a despotic enactment in flagrant conflict with democratic principles and with the spirit of free institutions.

Your Honor, I have stated in this court that I am opposed to the social system in which we live; that I believe in a fundamental change—but if possible by peaceable and orderly means.

Two years later Debs ran for president on the Socialist ticket for the fifth and final time. The slogan on a campaign poster in 1920 read, “From Atlanta Prison to the White House, 1920.” A popular campaign button showed Debs in prison garb, standing outside the prison gates, with the caption: “For President, Convict No. 9653.” Debs received nearly a million votes.

On Christmas Day 1921, President Warren G. Harding, a Republican, freed Debs and twenty-three other prisoners of conscience. By the time they were released, the socialist movement that Debs had helped build was dead, a victim of government repression and internal factional fighting between opponents and supporters of the new Bolshevik regime in Russia. But many of the ideas that Debs and the Socialist Party championed—including women’s suffrage, child labor laws, unemployment relief, public works jobs, and others—took hold after his death.