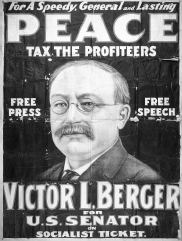

CREDIT: Wisconsin Historical Society/WHI-1901

DURING THE first quarter of the 20th century, two political forces—Robert M. La Follette’s progressivism and Victor Berger’s socialism—made Wisconsin a showcase for radical change. As the first Socialist elected to Congress, Berger organized the Socialist Party into an effective political organization, building on a base of Milwaukee’s large German immigrant population and its strong labor movement. Milwaukee in those days was, according to historian David Shannon, a “city of beer, German Brass bands, and bourgeois civic efficiency, . . . the strongest center of Socialist strength in the country.” Victor Berger was the center of Milwaukee socialism.

Berger was born in 1860 in Austria-Hungary to well-to-do parents and attended universities in Budapest and Vienna. He came to the United States in 1878, settled in Milwaukee, and soon became a German-language teacher in its public schools.

Berger was president of his local of the Typographical Union and a frequent delegate to the American Federation of Labor conventions. For years, he published newspapers in both German and English, distributing free editions to all Milwaukee homes on the eve of elections. In 1892 he bought the Wisconsin Vorwaerts (Forward), a daily German-language newspaper affiliated with the Socialist Labor Party (SLP).

In 1900 he joined with Eugene Debs to form the Social Democratic Party, which merged the following year with the SLP to form the Socialist Party of America. Berger closed the Vorwaerts and began a new paper, the Social Democratic Herald, which carried on its masthead the description “Official Paper of the Federated Trades Council of Milwaukee and the Wisconsin State Federation of Labor.” He was later editor of the Milwaukee Herald, an English-language labor paper owned primarily by the Brewery Workers union.

It was Berger who introduced Debs to socialism. In 1894 Debs was sentenced to six months in prison in Woodstock, Illinois, for violating a federal antistrike injunction during the Pullman strike. In jail, Debs read voraciously and began questioning many core beliefs, including his longtime membership in the Democratic Party. According to Debs: “Victor L. Berger—and I have loved him ever since—came to Woodstock, as if a providential instrument, and delivered the first impassioned message of socialism I had ever heard—the very first to set ‘the wires humming in my system.’”

Berger turned Milwaukee’s Socialist Party into a powerful political machine, using the newspaper, the backing of the unions, and the electoral strength of the German immigrant population. In 1910 Milwaukee voters elected Emil Seidel, the first Socialist mayor of a major city; the Socialists also won a majority of seats on the city council and the county board. At the same time, they made Berger the first Socialist elected to the US Congress. Both Seidel and Berger lost in 1912, but in 1916 Milwaukee voters elected another Socialist, Daniel Hoan, as their mayor and reelected him through 1940. Berger was reelected to Congress in 1918.

When they gained power in Milwaukee, the Socialists built new sanitation systems, municipally owned water and power systems, and community parks. They championed public education for the city’s working-class children. Proud of their efficient public services, they constantly boasted about Milwaukee’s excellent public sewer system under the Socialist municipal government. As both praise and irony, they were often known as “sewer socialists.”

In Congress, Berger sponsored bills providing for old-age pensions, government ownership of the radio industry, abolition of child labor, self-government for the District of Columbia, and a system of public works for relief of the unemployed, and he put forward resolutions for the withdrawal of federal troops from the Mexican border, for the abolition of the Senate (which was then not yet elected directly by the voters and was called the “millionaires’ club”), for women’s suffrage, and for federal ownership of the railroads.

But Berger was criticized by the Socialist Party’s left wing because, they argued, these measures, even if passed, would not add up to socialism. They criticized Berger’s “step at a time” brand of socialism. In fact, one of Berger’s favorite mottoes was, “Socialism is coming all the time. It may be another century or two before it is fully established.”

These differences came to a head at the Socialist Party’s 1912 convention, just as the party was gaining some success at electing members to local offices and launching Debs’s campaign for president. The left wing of the party was identified with the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW), the “Wobblies,” who believed in direct action rather than elections. At the meeting, Berger spoke bluntly about the split within the party’s ranks: “Anarchism is eating away at the vitals of our party. If there is to be a parting of the ways, if there is to be a split—and it seems that you will have it, and must have it—then, I am ready to split right here. I am ready to go back to Milwaukee and appeal to the Socialists all over the country to cut this cancer out of our organization.” Berger’s wing of the party prevailed. They kicked IWW leader William “Big Bill” Haywood off the Socialist Party’s national executive committee, prompting some of the left-wing faction to leave the party.

Like Debs, Berger was a leader in opposing the US entry into World War I. In an editorial on the mayoral election in the Milwaukee Leader, Berger wrote that the Socialist Party gave each voter a chance “to register his vote in favor of an immediate, general and democratic peace or for a bloody, long, drawn-out plutocratic war.”

After declaring war, Congress passed the Espionage Act to restrict opposition to the war effort. Americans could be imprisoned for “making false statements with intent to interfere with the operation or success of the military or naval forces.” The law allowed the US Postal Service to block any mail “advocating or urging treason, insurrection, or forcible resistance to any law of the United States.”

In 1918 Berger ran for the US Senate from Wisconsin. In his campaign he demanded the return of American troops from Europe and a system of taxation on war industries that would “take every penny of profits derived from the sale of war supplies.” He put up fifty billboards in Milwaukee that said, “WAR IS HELL CAUSED BY CAPITALISM. SOCIALISTS DEMAND PEACE. READ THE PEOPLE’S SIDE. MILWAUKEE LEADER. VICTOR L. BERGER, EDITOR.”

During the campaign, Socialist meetings were harassed by organized mobs and local chambers of commerce. Berger had difficulty hiring halls in which to speak outside Milwaukee. Socialist Party members distributing campaign literature were arrested without cause. Berger’s paper, the Milwaukee Leader (which he started in 1911 and which had a statewide circulation) was banned from the mails, so it could only be circulated in and near Milwaukee. In February 1918, in the middle of the campaign, Berger and four other Socialists were indicted under the Espionage Act. Despite this harassment, Berger won 26 percent of the vote statewide in the April Senate election. Berger was more successful the following November, when Milwaukee voters returned Berger to the congressional seat he had held from 1911 to 1913.

On February 20, 1919, Berger was convicted and sentenced by Judge Kenesaw Landis to twenty years in federal prison for his opposition to World War I. In April 1919 his colleagues in Congress expelled him by a 309–1 vote. Wisconsin’s governor, Emanuel Philipp, called a special election to fill Berger’s seat in December of that year, and again Berger won, only to be refused his seat still another time by a 328–6 margin.

Berger appealed Landis’s decision, and the US Supreme Court overturned it on January 31, 1921, ruling that Landis had improperly presided over the case after the filing of an affidavit of prejudice. Berger had been defeated for reelection in 1920, but he was reelected in 1922 and seated; he remained in Congress until 1927. Defeated again in 1928, Berger returned to Milwaukee and resumed his newspaper career until his untimely death in a streetcar accident the next year.