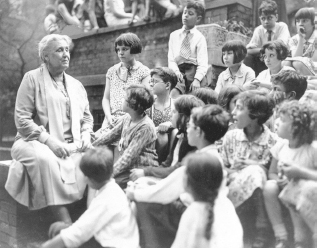

Jane Addams with Hull House children, 1933.

CREDIT: Associated Press

JANE ADDAMS was a key Progressive Era reformer, the founder of the settlement house movement, the “mother” of American social work, a champion of women’s suffrage, an antiwar crusader, and the 1931 winner of the Nobel Peace Prize. She carved out a new way for women to become influential in public affairs when many doors were closed to them.

Addams’s mother died when she was two. Jane and her four surviving siblings were raised by her father, John Addams, a businessman, banker, and landowner who served as an Illinois state senator from 1854 to 1870. Her evangelical Christian upbringing and her father’s abolitionist views influenced her commitment to social reform. One of the first generation of women to earn a college degree, she graduated from Rockford Female Seminary in 1881. She passed the first-year exams at the Women’s Medical College in Philadelphia, but back problems put her in the hospital immediately afterward and led to surgery nine months later. Never very good at science, she abandoned the idea of a career in medicine and began to search for some other career.

Even as a college graduate, Addams’s options were limited. Affluent women were expected to be happy as wives, mothers, and charity volunteers. A turning point came when she read about a new idea, the settlement movement, and about a settlement house that had been established in London. During a tour of Europe soon after, she visited that house, Toynbee Hall, which was a social and cultural center in Whitechapel, one of east London’s grittier working-class neighborhoods. It was founded to introduce male students at Oxford University, influenced by the ideas of Fabian socialism and social Christianity, to the realities of urban poverty. Even before her visit to London, Addams had proposed to her college friend Ellen Gates Starr that they start a settlement house in Chicago. Starr agreed, and Addams had found her career.

In 1889 Addams used the money she inherited after her father’s death to cofound with Starr the nation’s first settlement house in an industrial, mostly immigrant neighborhood of Chicago. They rented a run-down mansion named after its one-time owner, Charles Hull. Hull House was a place where prosperous young women and men could learn about the lives of working people and put into action their idealistic ideas of closing the divide between the social classes. The immigrants, many of whom did not speak English, lived in crowded, neglected tenements and worked in nearby factories.

Hull House offered clubs and classes and worked to be a good neighbor. Its residents opened a kindergarten, organized book-discussion groups and activities for children, nursed the sick, and started a lecture series on labor reform issues. Gradually, new facilities were added: an art gallery, a public kitchen, a gym, a coffee house, a cooperative boarding club for girls, a book bindery, an art studio, a music school, a drama group, a circulating library, and an employment bureau. By its fourth year, Hull House was host to 1,000 people every week.

Addams lived among workers who were organizing into unions and made friends with club women who had been politically active long before she arrived. After labor activist Florence Kelley joined the Hull House group in 1892, Hull House became a hub of social activism on labor issues and Addams became more deeply involved in the growing progressive movement.

Addams believed that well-educated upper-middle-class people should be the political allies of working people. Over the years, Addams and other Hull House residents, working alongside labor activists, pushed to end child labor and advocated for widows’ pensions (the precursor to Social Security), unemployment insurance, the minimum wage, labor-organizing rights, safe workplaces, affordable housing, special courts for juveniles, and freedom of speech. Addams first supported labor legislation in 1893, when she lobbied to reform sweatshops that employed small children. A representative of a manufacturers’ association offered to donate $50,000 to Hull House if Addams would “drop this nonsense about a sweat shop bill.” Addams said she would rather see Hull House close than accept a bribe.

Addams often used her connections among Chicago’s business and civic powerbrokers to raise money for Hull House, lobby for reforms, and intervene in political conflicts. During the 1894 Pullman strike, she was the most active member of the Citizens’ Arbitration Committee, created to try to mediate the conflict between the company and the union. Addams knew George Pullman, who had built his railroad car company on Chicago’s southern outskirts, and she fiercely hoped that Pullman would agree to meet with the Pullman chapter of the American Railway Union (led by Eugene Debs). Her efforts were unsuccessful, but her refusal to side with Pullman against the workers alienated some of Hull House’s wealthy benefactors, who stopped their donations.

Addams often served as a mediator in management-labor disputes, but she always affirmed workers’ right to organize, a position that put her at odds with many powerful friends and acquaintances. In an 1895 essay, “The Settlement as a Factor in the Labor Movement,” Addams wrote that “the organization of working people was a necessity” in order to “translate democracy into social affairs.” Those who did not recognize that “an injury to one” must be “the concern of all,” she observed, had fallen “below the standard ethics of (the) day.”

Hull House was the first settlement house in a white neighborhood to have an African American resident. Addams spoke out against lynching at the invitation of fellow Chicagoan Ida Wells-Barnett, invited W. E. B. Du Bois to speak at Hull House, and was a cofounder of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). As African Americans moved in greater numbers to Chicago and the Hull House neighborhood, they were welcomed at the settlement house.

Addams worked through local, state, and national groups to achieve the social reforms she fought for. She was a member of the National Child Labor Committee, a cofounder and board member of the Women’s Trade Union League, a member of the Chicago Board of Education, a vice president of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association, a vice president of the National American Woman Suffrage Association, a founding board member of the NAACP and the American Civil Liberties Union, and a member of the Progressive Party’s National Committee. The high point of her involvement in organized politics was in 1912, when she seconded the nomination of Theodore Roosevelt for president at the Progressive Party convention and campaigned for him in the midwestern states. Roosevelt said afterward that if he had been elected, he would have named Addams to his cabinet.

Addams and Hull House inspired many others to start settlement houses in other cities, the majority of them headed by women. By 1913 there were over 400 settlements in thirty-two states. Settlement houses laid the groundwork for the new profession of social work and for the emerging field of community organizing, but their other great influence was as places that educated generations of activists in a wide range of social and economic reform movements. Many of the most influential reformers and radicals in the 20th century were connected with the settlement house movement, including Lillian Wald, Mary Simkhovitch, Mary McDowell, Alice Hamilton, Florence Kelley, Frances Perkins, John Dewey, Roger Baldwin, Norman Thomas, and Eleanor Roosevelt.

Addams’s activism did not stop with domestic issues. In 1893 she joined the small and struggling Chicago Peace Society. She was attracted to the peace movement because of her belief in nonviolence, inspired by the writings of Leo Tolstoy. She gave her first speech about war and peace at an anti-imperialism rally in 1899, after the United States, having purchased the Philippines, began its war against those fighting for their independence.

When she opposed World War I, she argued that pacifists were patriots too and that killing was no way to settle international disputes. During the war, she cofounded the Woman’s Peace Party, whose agenda was peace and women’s rights, and cofounded what would eventually be called the Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom. She served as the league’s president until a few years before her death.