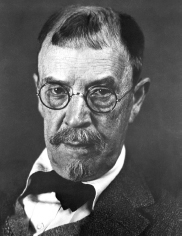

CREDIT: Associated Press

LINCOLN STEFFENS was the undisputed king of muckrakers. His exposés of corruption shocked the nation, changed public opinion, and provided ammunition for reformers. A man of warmth, humor, and compassion, Steffens was a social chameleon, mixing with all sorts of people, including Wall Street bankers, social reformers, union activists, and Tammany Hall bosses, who over the years educated him on the insidious ways of municipal corruption. His goal was not simply to uncover graft but to eliminate what he called “the affliction of privilege in American society.”

Raised in a wealthy family in Sacramento, California, Steffens was an indifferent student if the subject bored him but a serious scholar when his interest was piqued. He did poorly at the University of California, but he convinced his father to pay for him to study art and philosophy in Germany and France for three years. He returned to the United States in 1892, landing his first job in New York as a reporter for the Evening Post.

In 1902, while working for McClure’s Magazine, Steffens traveled to St. Louis, Missouri, and met Joseph W. Folk, a crusading prosecutor, who gave the journalist a guided tour of business and political corruption. That October, McClure’s published what many consider the first muckraking article, “Tweed Days in St. Louis,” which earned Steffens a national reputation. Steffens wrote, “Go to St. Louis and you will find the habit of civic pride in them. The visitor is told of the wealth of the residents, of the financial strength of the banks, and of the growing importance of the industries; yet he sees poorly paved, refuse-burdened streets, and dusty or mud-covered alleys; he passes a ramshackle firetrap crowded with the sick and learns that it is the City Hospital.”

In St. Louis every transaction, including getting legislation passed or defeated, involved a bribe. The exposé had such an impact that the magazine sent Steffens around the country to uncover other scandals, which resulted in a series of articles. In 1904 they were published as a book, The Shame of the Cities, making Steffens one of the most famous journalists in the nation.

He next set his sights on state governments. As he recalled in his 1931 Autobiography, states had the same unhappy pattern as city administrations: “the same methods, the same motives, purposes, and men, all to the same end: to make the State officials, the Legislature, the courts, parts of a system representing the special interests of bribers, corruptionists, and criminals.” His 1906 book, The Struggle for Self-Government, inspired reformers, as did his stories of valiant fighters trying to right political wrongs, collected in his 1909 book, Upbuilders.

In 1906 Steffens and his colleagues Ida Tarbell and Ray Stannard Baker launched their own publication, American Magazine, to expand their investigative efforts. But Steffens wanted to go beyond exposing wrongdoing. He wanted the magazine to propose solutions, an idea his colleagues rejected. Unsatisfied, Steffens soon left the magazine to work as a freelancer. In 1908 he interviewed and wrote an admiring profile of Socialist Eugene Debs, who was running for president, in Everybody’s magazine.

The following year, Steffens thought he had found his opportunity to remedy municipal corruption when Edward Filene, a wealthy department store magnate and progressive philanthropist, invited him to Boston. Filene wanted to turn Boston into a model of social reform. Filene was as well connected as anyone in Boston, and for almost a decade he and a handful of other progressives (mostly business and professional men, including Louis Brandeis), tried to challenge the corruption of the city’s political machine. They hoped to advance public health and education reforms and to win popular control over street railway, gas, and subway franchises, but they had little success. Filene secured $10,000 from the Good Government Association (GGA) and asked Steffens to spend a year in the city investigating Boston’s political corruption and then to draft a plan for change. Steffens interviewed business leaders, social workers, reporters, Harvard professors, and others. He visited neighborhoods, collected statistics, gave speeches, and was toasted at receptions in his honor as Boston’s municipal savior. One of his talks at Harvard mesmerized two students—Walter Lippmann and John Reed—who would become his protégés and then famous progressive writers themselves.

But by the time Steffens was ready to write his report, Filene’s business colleagues in the GGA had gotten cold feet. Much to Steffens’s and Filene’s chagrin, they balked at even modest reforms, such as an increase in taxes, much less municipal ownership of key utilities. Discouraged, Steffens never finished the book he had planned to write.

After Steffens’s wife died in 1911, he took solace in his Christian faith. He was particularly inspired by Sam “Golden Rule” Jones, a wealthy businessman and reform mayor of Toledo, who in both his business and his political practices lived by Christian principles of charity and compassion. Steffens wrote a series of articles about applying these principles in the real world.

In 1911, to test his ideas, Steffens traveled to Los Angeles, where the controversial trial of the two McNamara brothers was taking place. The brothers, union activists involved in a bitter citywide labor dispute, were accused of dynamiting the Los Angeles Times building, killing twenty-one employees in the process. Steffens met with Harrison Gray Otis (who owned the Times), leaders of the business community, and Clarence Darrow (who represented the brothers) and other members of the defense team. Steffens then hatched a plan to apply the Christian principle of “do unto others.” In his plan, the brothers would plead guilty (which many believed they were), but the judge would show them leniency. In exchange, the city’s labor leaders would call off an ongoing strike and begin negotiations.

But the deal fell apart when church ministers the Sunday before the verdict preached vengeance and denounced Steffens’s proposal. “It is no cynical joke, it is literally true, that the Christian churches would not recognize Christianity if they saw it,” Steffens wrote. “They came like the cries of a lynching mob and frightened all the timid men who had worked with us—and the judge.”

After his experiences in Boston and Los Angeles, Steffens gave up hope that exposing corruption or proposing practical solutions would, on their own, lead to reform. Entrenched business interests, he concluded, would always outwit and outlast the reformers. Steffens became an unabashed revolutionary and looked for examples elsewhere that American radicals might follow. In December 1914 he boarded a ship from New York to Veracruz to see for himself what the Mexican Revolution was all about. He was trying to determine which of two competing leaders of the revolution—Francisco “Pancho” Villa or Venustiano Carranza—was the one to support. “I thought of a trick I used to practice in making a quick decision in politics at home,” he wrote in his autobiography. “I’d ask Wall Street, which is so steadily wrong on all social questions. If I could find out which side Wall Street was on, I could go to the other with the certainty of being right.” So he sat down with the “big business men with Mexican interests,” who were happy to tell him why Villa was the better man. He then set sail to meet Carranza.

Steffens did not speak Spanish, but Carranza later said the American journalist “speaks our language”—that of revolution. Carranza asked Steffens to advise the revolutionaries on developing a constitution, but Steffens was there to learn, not to teach. In 1916, upon his return, he wrote an article in Everybody’s magazine arguing that the greatest danger to the revolution was potential American military intervention at the behest of US and Mexican business interests. Senator Robert M. La Follette and the Woman’s Peace Party, echoing Steffens’s view, sought to mobilize opposition to sending US troops. Steffens met with President Woodrow Wilson and urged him to hold off on a planned counterrevolutionary invasion of Mexico. Wilson had already ruled out an invasion but flattered Steffens by telling him that his firsthand account of Mexican politics had been persuasive.

Next, Steffens traveled to Russia to witness that country’s unfolding revolution. After seeing the emerging socialist state, he famously said, “I have seen the future and it works.” But Steffens’s enthusiasm for the Soviet Union did not last. By the time he wrote his autobiography in 1931, he had become disillusioned with communism. Frustrated by reform and disenchanted by revolution, Steffens could not see the important role he had played in shaping American public opinion and in making it easier for Progressive Era activists to build a movement to strengthen democracy.