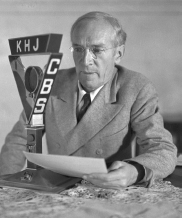

CREDIT: Associated Press

“I AIMED at the public’s heart,” said Upton Sinclair, “and by accident hit its stomach.” Sinclair was referring to the response to his best-selling 1906 novel The Jungle, about conditions in Chicago’s meatpacking industry. The book focused on the horrible conditions under which immigrants and their families worked and lived in the “Packinghouse” area of Chicago. Sinclair portrayed the grueling life of Lithuanian immigrant Jurgis Rudkus, whose backbreaking job in the slaughterhouse and miserable slum housing nearby almost destroys his soul as well as his body. But readers focused instead on Sinclair’s graphic descriptions of the unsanitary process by which animals became meat products. The public outrage triggered by the book—based on Sinclair’s two-month visit to Chicago during a bitter stockyard strike in 1904—led Congress to pass the Pure Food and Drug Act and the Meat Inspection Act in 1906, the first federal laws regulating corporate responsibility for consumer products.

A Pulitzer Prize–winning author, Sinclair wrote ninety books, mostly factual studies of powerful institutions or novels that exposed social injustice. In 1934, in the depths of the Depression, he ran for and was almost elected governor of California on the End Poverty in California (EPIC) platform.

Born into a comfortable Baltimore, Maryland, family, he entered City College of New York at age fifteen. He began writing sketches—mostly adventure stories—for magazines to pay his expenses. After graduation, he became a full-time writer. His first novel, Springtime and Harvest (1901), was a modest success.

Around this time Sinclair began reading Karl Marx and the radical economist Thorstein Veblen and joined Eugene Debs’s three-year-old Socialist Party. J. A. Wayland, the editor of the Appeal to Reason, a socialist newspaper, challenged Sinclair to write a novel about “wage slavery.” So Sinclair headed to Chicago to investigate conditions in the meatpacking industry. A handful of powerful companies controlled the industry, using their political influence to keep the government off their backs. Livestock from midwestern farms were sent to company pens in Chicago, slaughtered, and packed into consumer products. The companies recruited immigrants from Eastern and Central Europe who performed backbreaking work in filthy and dangerous conditions. Many workers stood all day on floors covered with blood, meat scraps, and foul water. They worked six days a week, ten hours a day, and earned pennies an hour.

In The Jungle, Sinclair turned his observations into the gruesome details of Jurgis’s daily life in Chicago’s slums and slaughterhouses. He described workers falling into open cooking vats, amputated fingers being ground into sausage, and diseased cattle being hit with sledgehammers and processed through the slaughterhouses. In one scene, he describes the infiltration of rats:

There would be meat stored in great piles in rooms; and the water from leaky roofs would drip over it, and thousands of rats would race about on it. It was too dark in these storage places to see well, but a man could run his hand over these piles of meat and sweep off handfuls of the dried dung of rats. These rats were nuisances, and the packers would put poisoned bread out for them; they would die, and then rats, bread, and meat would go into the hoppers together.

Sinclair serialized his story in the Appeal to Reason and then published the series as a book. It sold 100,000 copies in the first year and was quickly translated into seventeen languages. It even led to a brief upsurge in vegetarianism. President Theodore Roosevelt, who had seen soldiers die from eating rotten meat during the Spanish-American War, invited Sinclair to the White House and pushed Congress to pass the first consumer safety laws.

The Jungle turned Sinclair into a national celebrity. He used the money from the book to start what he hoped would be a socialist experiment in communal living. He purchased a former boys’ school in Englewood, New Jersey, and renamed it Helicon Hall. Although many famous people—William James, Emma Goldman, Lincoln Steffens, and John Dewey among them—visited Helicon Hall, newspapers wrote scandalous stories about it, gossiping about “free love” experiments that were probably fiction. In March 1907 the building mysteriously burned down.

Sinclair lost his money, but he kept writing at a hectic pace. In The Metropolis (1908), he described the morally bankrupt social world of New York’s fashionable rich. In The Moneychangers, published the same year, he used fiction to attack financier J. P. Morgan. In King Coal (1917), he wrote about the Ludlow Massacre, in which John D. Rockefeller’s coal empire called out the state militia and private thugs to put down a coal miners strike by killing twenty people, both workers and members of their families. The Profits of Religion (1917) is an incendiary attack on organized religion. The Brass Check (1920) indicted the American newspaper business and its business-friendly journalism. Goose Step (1923) dealt with the corruption of higher education as a tool of big business. Oil! (1927) exposed the corruption of California’s oil industry. In Boston (1928), Sinclair wrote a two-volume fictionalized account of the Sacco-Vanzetti case, in which two Italian immigrants, Nicola Sacco and Bartolomeo Vanzetti, both anarchists, were unfairly convicted and executed for murder.

In 1916 Sinclair and his second wife moved to California, settling in Pasadena and then Monrovia, both suburbs of Los Angeles. There he got involved in radical politics. Sinclair ran on the Socialist ticket for the US House of Representatives (1920), for the US Senate (1922), and for governor (1926 and 1930), winning few votes but using the campaigns to promote his left-wing views.

After Franklin D. Roosevelt was elected president in 1932, Sinclair figured he might have more influence running for office as a Democrat. Like most Socialists, he supported the New Deal but thought it did not go far enough, allowing business to undermine its more ambitious goals. Sinclair joined the Democratic Party, wrote a sixty-four-page pamphlet outlining his economic plan—I, Governor of California and How I Ended Poverty, which he published himself—and declared his intention of running in the Democratic primary for California governor in 1934.

Sinclair’s plan focused on the idea of “production for use.” The thousands of factories that were either idle or working at half capacity would be offered the opportunity to rent their plants to the state of California, hire back their workers, and run their machinery “under the supervision of the state.” The workers would turn out goods and would own what they produced. Similarly, farmers, who were producing huge quantities of unsold foodstuffs, would be invited by the state to bring their produce “to [state] warehouses,” where they would “receive in return receipts which will be good for . . . taxes.” The farmers’ food would be “shipped to the cities and made available to the factory workers in exchange for the products of their labor.”

Much to Sinclair’s surprise, his pamphlet became a best seller across California. And his campaign turned into a grassroots movement. Thousands of people volunteered for his campaign, organizing EPIC clubs across the state. The campaign’s weekly newspaper, the EPIC News, reached a circulation of nearly 1 million by primary day in August 1934.

The campaign allowed Sinclair to present his Socialist ideas as commonsense solutions to California’s harsh economic conditions. Sinclair shocked California’s political establishment (and himself) by winning the Democratic primary. Dozens of other progressive candidates, running on the EPIC platform, also won Democratic primary races for the legislature. Many experts predicted that Sinclair had a good chance to beat the sitting Republican governor Frank Merriam, a colorless politician trying to defend the GOP’s probusiness views at a time of massive unemployment and misery.

A few days after the primary, Sinclair took a train to meet FDR in Hyde Park, New York, hoping to persuade the popular president to endorse him. FDR’s progressive advisers, including his wife Eleanor Roosevelt and Harry Hopkins, thought he should support Sinclair, but his more conservative aides, including his political director, Jim Farley, feared that Sinclair was too radical and would hurt the Democrats’ chances of winning a big victory in the congressional midterm elections that year. The president made no endorsement that day, nor would he do so later on.

Despite FDR’s stance, Sinclair’s campaign took off. Fearing a Sinclair victory, California’s powerful business groups mobilized an expensive and effective dirty tricks countercampaign. Almost every day, the right-wing Los Angeles Times mocked Sinclair by publishing quotations from his books taken out of context. The papers only covered Merriam’s campaign, ignoring Sinclair’s daily speeches and events. One Hollywood studio produced a phony newsreel, with actors playing jobless hoboes riding trains to California to take advantage of Sinclair’s promised welfare handouts. The newsreel was shown in movie theaters across the state as if it were a documentary.

Then FDR’s aide Farley sent an emissary to California to cut a deal with Merriam. If the Republican governor would support the New Deal, FDR would not endorse Sinclair. FDR’s silence hurt Sinclair. On election day, Merriam got 48 percent of the vote, and Sinclair got 37 percent of the vote—twice the total for any Democrat in the state’s history. A third candidate (promoted by conservative Democrats to take votes away from Sinclair) got 13 percent.

Sinclair’s campaign had such reach that his ideas pushed the New Deal to the left. After the Democrats won a landslide midterm election in Congress that year, FDR launched the so-called Second New Deal, including Social Security, major public works programs, and the National Labor Relations Act.

In California, Sinclair’s campaign had a lasting impact. A state long dominated by the Republicans became a two-party state. Two dozen EPIC candidates won election to the state legislature, including future members of Congress Augustus Hawkins (California’s first black member of Congress) and Jerry Voorhis. The following year, several labor, progressive, and radical organizations in Los Angeles formed the United Organization for Progressive Political Action, and three of its candidates won election to the city council. Another EPIC supporter, Culbert Olson, was elected governor in 1938. The EPIC clubs continued and became the foundation of the state’s burgeoning liberal Democratic movement, the California Democratic Clubs, which helped elect liberal Edmund “Pat” Brown as governor in 1958. Sinclair’s EPIC campaign inspired many younger progressives to challenge business-oriented candidates in Democratic primaries, including Tom Hayden in his insurgent 1976 primary campaign against incumbent US senator John Tunney.

After the election, Sinclair returned to writing novels. The Flivver King: A Story of Ford-America (1937) is a fictionalized indictment of Henry Ford and his use of “scientific management” to replace skilled workers and impose rigid and dehumanizing conditions in his factories. The United Auto Workers published the book to educate and agitate its members, only months before the landmark sit-down strike in Flint, Michigan. Between 1940 and 1953 he wrote eleven novels based on the character Lanny Budd, who always finds himself in the middle of decisive moments in history. One of them, Dragon’s Teeth (1942), about the rise of Nazism in Germany, won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction.