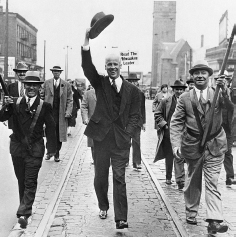

Norman Thomas, center, Socialist Party candidate for president, leads parade in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, in 1932. CREDIT: Associated Press

IN OCTOBER 1967, eighty-two-year-old Norman Thomas—blind and crippled by arthritis and a recent automobile accident—took the podium to address a meeting of college students in Washington, DC. Many were angry at the United States for conducting what they considered an immoral and imperialist war in Vietnam. Over the previous few years of escalating demonstrations, protesters would occasionally burn the American flag. That symbolic act, inevitably highlighted on TV news and featured in the next day’s newspapers, led many Americans to conclude that people who opposed the war also hated the United States. Thomas, a lifelong pacifist and Socialist, as stalwart a foe of the Vietnam folly as anyone, raised the moral stakes by proclaiming, “I don’t like the sight of young people burning the flag of my country, the country I love. A symbol? If they want an appropriate symbol, they should be washing the flag, not burning it.”

It was for actions like that that Thomas was often called “America’s conscience.” He was the nation’s most visible Socialist from the 1930s through the 1960s, and he could easily have been marginalized by mainstream politics, especially when he ran for office, as he frequently did, against reform-oriented Democrats. Instead, Thomas was a constant and effective presence in battles for workers’ rights, civil liberties, civil rights, peace, and feminism. He was influential because of his great moral authority, his spellbinding oratory, and his leadership of broad coalitions of radicals and reformers who put aside ideological differences to win progressive victories. The British journalist Alistair Cooke wrote about Thomas, “He always lost the election and always grew in influence and dignity with every defeat.”

Thomas’s father, grandfather, and great-grandfather were conservative Presbyterian pastors. After attending Princeton University, he followed in their footsteps, enrolling in Union Theological Seminary, and he was ordained a minister in 1911. But by then he had been inspired by the emerging Christian Social Gospel movement, which viewed religion as a vehicle for social reform. He turned down an offer to head the wealthy Brick Presbyterian Church on Fifth Avenue in New York City to serve an ethnically diverse parish in East Harlem, a poor neighborhood. Like many other middle-class reformers of the era, Thomas also headed a settlement house in the area to serve the needs of the poor.

Thomas was drawn to both pacifism and Christian socialism, and in 1917 he supported the antiwar Socialist candidate Morris Hillquit for mayor of New York. In a letter to Hillquit that Thomas released to the press, Thomas wrote, “I believe that the hope for the future lies in a new social and economic order which demands the abolition of the capitalistic system.” The letter angered the well-off leaders of the Presbyterian hierarchy. Contributions to his church and to its charitable work with the poor fell sharply, and he resigned from the ministry and took a job running the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), a pacifist group, and its magazine, World Tomorrow. Outraged by the government’s persecution and jailing of antiwar activists, Thomas joined with Roger Baldwin to create the National Civil Liberties Bureau (NCLB), which was later renamed the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU). In addition to his duties with FOR, Thomas took the helm of the NCLB after Baldwin went to prison for refusing to register for the draft.

Although he never held a pulpit or worked for a church group again, Thomas maintained his strong religious views. He wrote frequently for Christian publications until 1921, when he joined The Nation magazine as associate editor, and he served briefly as editor of the New York Leader, a short-lived socialist daily newspaper.

Thomas considered socialism an extension of liberal democracy and the Christian Gospels, and he viewed communism as the opposite of his basic values. He joined the Socialist Party just as it was facing brutal repression. Its political leaders were sometimes barred from taking office, even after winning an election. Eugene Debs was in jail for his opposition to World War I. When the party’s meetings were not banned by local authorities, the gatherings were targeted and attacked by local thugs and right-wingers. Its foreign-born members were threatened with deportation. In addition, the Communist Party—which had close ties to Russia’s revolutionary government—competed for members and siphoned off some of the Socialist Party’s more left-wing activists. The Socialist Party’s membership fell from more than 100,000 in 1917 to barely 12,000 by 1923.

Thomas refused to let the Socialist Party die. For years, he crisscrossed the country giving speeches to unions, women’s groups, religious organizations, colleges, peace groups, civil rights organizations—wherever he could find an audience. To spread the Socialist Party message, he ran for office relentlessly, never expecting to win but always hoping to win new followers and to influence what other candidates were advocating.

After running unsuccessfully for four local and state offices on the Socialist ticket, Thomas ran for president first in 1928 and then five more times. Debs had died in 1926, and neither of the Socialist Party’s two top political leaders—Victor Berger and Hillquit—were eligible to run for president due to their foreign birth. Thomas became the party’s national leader.

In 1932, in the depths of the Depression, the Socialist platform called for old-age pensions, public works projects, a more progressive income tax, unemployment insurance, relief for farmers, slum clearance and subsidized housing for the poor, a shorter workweek, and the nationalization of banks and basic industries. Thomas figured that in such desperate times, his message would appeal to voters. But many voters who may have agreed with Thomas’s views did not want to “waste” their vote on a Socialist who had no chance to win and who might even take enough votes away from the Democratic candidate, Franklin D. Roosevelt, to keep Republican Herbert Hoover in office. Thomas had little regard for FDR, whom he considered a wealthy dilettante and a lackluster governor of New York. He believed FDR’s 1932 platform offered few specifics except vague promises of a “New Deal.”

Thomas did not expect to win, but he was disappointed that whereas FDR garnered 22.8 million votes (57 percent), he had to settle for 884,781 (2 percent). When friends expressed delight that FDR was carrying out some of the Socialist platform, Thomas responded that it was being carried out “on a stretcher.” He viewed the New Deal as patching, rather than fixing, a broken system. He wanted FDR and Congress to socialize the banks and expand credit for job-creating businesses, including public and cooperative enterprises. Instead, FDR bailed out the financial system with some modest regulations “and gave it back to the bankers to see if they could ruin it again.”

Although Americans rejected Thomas’s bids for office, many still admired his principled stands on issues. He remained a public figure, an eloquent and sometimes fiery speaker, frequently quoted in the news and a constant presence at rallies and conferences and in the pages of liberal and radical publications. He was a nonstop crusader for workers’ rights, women’s rights (including birth control), and civil rights.

In 1926 Thomas was arrested for speaking to the strikers in Passaic, New Jersey, challenging the local sheriff’s imposition of martial law. His arrest gave the ACLU an opportunity to obtain an injunction against the sheriff for his violation of civil rights. In 1933 Thomas and others were attending a conference of radicals and progressives in Washington, DC, staying at the Cairo Hotel. When the hotel barred Floria Pinkney, an African American delegate, Thomas led a march on the hotel and canceled the group’s reservations. In 1934 Thomas persuaded H. L. Mitchell, a former Tennessee sharecropper who ran a dry-cleaning shop in Arkansas and was a Socialist, to form the Southern Tenant Farmers Union, one of the first racially integrated labor unions. Thomas often traveled to the rural South to help organize the sharecroppers and was occasionally beaten and arrested.

In 1935 Thomas led a national campaign against the Ku Klux Klan and rogue cops in Tampa, Florida. The Klan members and their police accomplices had abducted and beat three local radicals, one of whom—Joseph Shoemaker, a Socialist Party member—died from the wounds. The ACLU offered a $1,000 reward for information leading to the arrest and conviction of the guilty persons. The national attention prompted some Florida newspapers, civic and religious leaders, and the local sheriff to condemn the violence and bring the thugs to justice.

In the late 1930s, concerned that big business and FDR were preparing America for another major war, Thomas made alliances with anyone who shared his opposition, including anti-Semites and racists whose views he opposed. It was Thomas’s most serious political mistake. Three days after the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor, however, Thomas reluctantly announced his support for America’s war effort. During the war, Thomas was one of the few public figures to oppose the internment of Japanese Americans. He also pleaded with FDR to allow Jewish refugees into the country to escape the Holocaust. He worked closely with A. Philip Randolph, an African American union leader, pushing FDR to integrate the nation’s defense factories and abolish discrimination in the nation’s armed forces.

Thomas vigorously protested President Harry S. Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb to destroy Hiroshima and Nagasaki. After the war, and despite his strong opposition to communism, he defended the civil liberties of American Communists during the McCarthy era.

In 1957 Thomas cofounded the Committee for a SANE Nuclear Policy to halt the escalating arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union. He spoke relentlessly on SANE’s behalf. In 1960 he addressed a SANE rally in Madison Square Garden, along with Randolph, Eleanor Roosevelt, Walter Reuther, and singer Harry Belafonte; the rally attracted 20,000 people. In 1961, Tom Hayden, the leader of Students for a Democratic Society, wrote that his generation only trusted three people over thirty: sociologist C. Wright Mills, Socialist writer-activist Michael Harrington, and Thomas.

In December 1964, 2,000 Americans gathered at New York’s Hotel Astor to celebrate Thomas’s eightieth birthday. Thomas used the occasion to call for a cease-fire in Vietnam. He received hundreds of congratulatory telegrams from prime ministers, politicians, labor leaders, and social activists, including US Supreme Court Chief Justice Earl Warren and Vice President Hubert Humphrey. Martin Luther King Jr., on his way to Oslo to accept the Nobel Peace Prize, taped a message to Thomas and later published it as an article entitled “The Bravest Man I Ever Met.” In it, he said, “I can think of no man who has done more than you to inspire the vision of a society free of injustice and exploitation. While some would adjust to the status quo, you urged struggle. Your example has ennobled and dignified the fight for freedom, and all that we hear of the Great Society seems only an echo of your prophetic eloquence.”

A plaque in the Princeton University library reads: “Norman M. Thomas, class of 1905. ‘I am not the champion of lost causes, but the champion of causes not yet won.’”