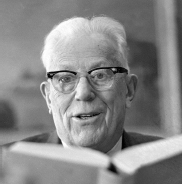

CREDIT: Associated Press/Henry Burroughs

WHEN REPUBLICAN president Dwight D. Eisenhower nominated California’s Republican governor Earl Warren to the US Supreme Court, he thought he was appointing a conservative jurist. Later, Eisenhower reportedly said that it was the “biggest damn fool mistake” he had ever made. Warren, chief justice from 1953 to 1969, took the Supreme Court in an unprecedented liberal direction. The Warren Court, which also included liberal justices William O. Douglas, William J. Brennan, and Hugo Black, dramatically expanded civil rights and civil liberties.

As a county prosecutor, state attorney general, and governor, Warren was probusiness, tough on crime, and zealously antiradical, even anti–New Deal. But once he was appointed to the Supreme Court, his other traits—a strong sense of fair play and respect for individual liberties—prevailed.

Warren used his considerable political skills to guarantee that the 1954 ruling in Brown v. Board of Education was unanimous. In two other landmark decisions, Baker v. Carr (1962) and Reynolds v. Sims (1964), the Warren Court established the principle of “one man, one vote,” which ended the overrepresentation of rural areas in state legislatures.

In another milestone case, Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), the Warren Court ruled that in criminal cases courts are required to provide attorneys for defendants who cannot afford their own lawyers. In New York Times Co. v. Sullivan (1964), the Court significantly expanded free speech by requiring proof of “actual malice” in libel suits against public officials and public figures. The 1965 Griswold v. Connecticut decision established the right to privacy and laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade (1973), the post-Warren ruling that gave women the right to have an abortion.

Anyone who watches a cop show on television knows that criminal suspects have a “right to an attorney” and a “right to remain silent.” It was the Warren Court, in Miranda v. Arizona (1966), that ruled that detained suspects, prior to police questioning, must be informed of their constitutional rights to an attorney and against self-incrimination.

Warren’s father was a longtime employee of the Southern Pacific Railroad. He lost his job after participating in the failed Pullman strike of 1894, led by Eugene Debs. Warren grew up in Bakersfield, California, graduated from the University of California, Berkeley, in 1912, and then graduated from its law school two years later. He worked for a year as counsel to an oil company, spent several years in private practice, and joined the Alameda County (Oakland), California, district attorney’s staff as a deputy district attorney.

After running for and serving for thirteen years as Alameda County district attorney, Warren was elected California’s attorney general in 1938. In that position, he played a key role in detaining Japanese Americans during World War II. After the Japanese bombed Pearl Harbor in December 1941, Warren and others believed that Japanese Americans posed a security risk as potential spies and saboteurs on behalf of Japan. Thousands of Japanese Americans lost their property and businesses. Only in retirement did Warren acknowledge that the relocation was a mistake based on hysteria.

In 1942 Warren was elected governor, and he was reelected in 1946 and 1950. During his administration, he expanded the state’s higher education system and raised gasoline taxes to develop California’s highway system. In 1948 he was the Republican Party’s vice presidential candidate on a ticket with Thomas Dewey, which lost to incumbent Harry S. Truman. It was the only election he ever lost.

It was an accident of timing that Warren’s first major test as chief justice, one that ultimately defined his reputation as a liberal and activist jurist, was Brown v. Board of Education. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People’s legal team, led by Thurgood Marshall, had worked for years to bring cases to lower courts challenging laws mandating the segregation of public schools, hoping to chip away at the entrenched doctrine. Many of the plaintiffs took enormous personal risks to defy the Jim Crow status quo.

Finally, in December 1952, the Court heard the arguments in the Brown case. Under Chief Justice Fred Vinson, the Court was deeply divided on whether school segregation was constitutional. Vinson had written the Court’s opinions ordering the admission of the black students to all-white universities in Texas and Oklahoma, but several of his Court colleagues believed that when it came to public schools, he favored maintaining the “separate but equal” precedent adopted in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

In June 1953 the Court ordered the reargument of the Brown case. Vinson died in September before the new hearing took place. In what may be an apocryphal story, Justice Felix Frankfurter, thinking about the upcoming reargument, stated that Vinson’s death “is the only evidence I have ever had for the existence of God.”

Eisenhower appointed Warren the chief justice before the Court heard the new arguments in the Brown case in December 1953. Knowing that the decision would be politically controversial, Warren sought a unanimous decision. He assigned the job of writing the opinion to himself, and then, like a shrewd politician, he met with each of his eight colleagues separately and listened to their views in order to construct a decision that they could all agree on. After he brought the last holdout, Justice Stanley Reed, on board, Warren drafted the ruling. “We cannot turn the clock back,” Warren wrote. “We must consider public education in the light of its full development and its present place in American life throughout the Nation. Only in this way can it be determined if segregation in public schools deprives these plaintiffs of the equal protection of the laws.”

Although the decision narrowly held that Plessy’s “separate but equal” formula did not apply to the field of public education, the decision was explosive in terms of its political impact. It helped trigger a new wave of civil rights activism and also catalyzed a countermovement of resistance to desegregation, particularly in the South. Warren suggested the Court delay for a year the order implementing its decision. In the Brown II decision, issued on May 31, 1955, the Court ordered that school districts be desegregated “with all deliberate speed.”

Eisenhower was angry at Warren for the Brown ruling. According to Warren’s memoirs, Eisenhower told him that southerners “are not bad people. All they are concerned about is to see that their sweet little girls are not required to sit in school alongside some big overgrown Negroes.”

The Brown decision made Warren a controversial public figure. A grassroots movement emerged throughout the South, including the rise of groups such as the White Citizens Council and a new wave of Ku Klux Klan activism, to defy the Court’s ruling. One hundred and one members of Congress, all from the South, signed the Southern Manifesto pledging to defy court-ordered desegregation. Billboards erected by the right-wing John Birch Society saying “Impeach Earl Warren” dotted the South and elsewhere.

Many of the Warren Court’s later decisions also outraged conservatives, who believed that the Republican politician had become a judicial activist, making social policy and upending the Founding Fathers’ ideas about the Constitution. During his 1968 campaign for president, Richard Nixon pledged to appoint a Supreme Court justice who would overturn the Warren Court’s rulings.

Although critics have accused Warren of being a judicial activist, his decisions simply exposed the political nature of the Supreme Court and of the judiciary in general. The Court’s rulings have always tended to reflect at least three overlapping influences: the ideological views of the presidents who appoint justices, current events and public opinion, and the legal outlooks of the justices. Twenty-first century rulings by Republican-appointed Court majorities—such as the 5–4 Bush v. Gore ruling that handed George W. Bush the presidency in 2000 and the 5–4 Citizens United v. Federal Election Commission decision in 2010 to give corporations the unlimited ability to contribute to political campaigns—are examples of how conservative justices often interpret the Constitution to justify their own political and ideological activist agendas.

As chief justice, Warren may have been ahead of public opinion on many civil liberties and civil rights issues, but he was in sync with what Martin Luther King Jr. called the arc of history, helping to bend it toward justice.