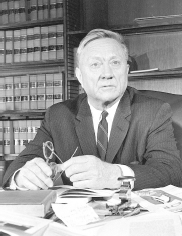

CREDIT: Associated Press

IN 1954 the Washington Post published an editorial supporting a government plan to pave a strip of land adjacent to the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal. The canal had been defunct as a mode of transportation since 1924, and in 1938 the government had purchased the right-of-way. Hoping to encourage more people to use the area, Congress suggested turning the land into a road for cars. US Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas responded with a letter to the editor, publicly challenging the editor to accompany him on a trek along the full 185 miles of canal.

Not only did a number of Post editors take him up on the offer, so too did dozens of conservationists and scientists—fifty-eight in all. As word spread, members of the public joined in the hike, and schoolchildren cheered as the group passed through towns along the way. Faced with a driving snowstorm and other hardships, only nine men, including Douglas, successfully completed the eight-day hike. On the last day, Douglas organized a committee to shepherd the establishment of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal National Historical Park, today one of the most heavily visited parks in the country.

Douglas was not only an outspoken environmentalist but also the strongest civil libertarian to ever sit on the Supreme Court. Appointed by Franklin D. Roosevelt in 1939 at age forty, he was both the youngest justice on the Court and the longest serving, with thirty-six years on the bench. In addition to his legal opinions, he also wrote more than thirty books.

Although he came from humble roots, his adoring mother, who called him “Treasure,” always told him he was destined for greatness, even repeatedly rehearsing a mock presidential nominating speech for him when he was a small boy. His father, an itinerant preacher, died when Douglas was six, and his mother moved the family to Yakima, Washington.

Money was a constant struggle, and his education was nearly derailed several times because he could not pay tuition. He received a scholarship from Whitman College in Walla Walla, Washington, where he became a champion debater and graduated Phi Beta Kappa in 1920. After teaching school for two years, he was accepted into Columbia University Law School.

After brief stints at a Wall Street firm and teaching at Columbia, he was recruited to teach at Yale Law School in 1928 by its youthful dean, whom Douglas had met one evening while drinking—during Prohibition—at the Pelham Country Club.

With the election of FDR in 1932, Douglas set his sights on working for the administration. He became an authority on the Securities Act of 1933, publishing seven major articles on the new law. In 1934 he was asked to join the Securities and Exchange Commission and became its chair in 1937. He was a close adviser to FDR on the regulation of corporations, an issue that led many conservatives to attack the president as well as Douglas.

FDR appointed Douglas, then forty, to the Supreme Court in 1939 to replace Louis Brandeis, who had retired. The Senate Judiciary Committee’s hearing on Douglas, which occurred only four days after the president’s announcement, lasted five minutes.

Douglas carried his suspicion of corporate power to the bench, writing in his memoir The Court Years: 1939–1975, “I was always denounced as an activist; so were Black, Warren, Tom Clark, Brennan and others. And we were ‘activists’—not in reading our individual notions of the public good into the Constitution and/or the laws, but in trying to construe them in the spirit as well as the letter in which they were enacted.”

Despite his reputation as a civil libertarian, Douglas sided with the Court majority in the notorious 1944 Korematsu v. United States opinion affirming the constitutionality of the wartime internment of Japanese Americans.

Douglas was bored by his life on the Supreme Court, and he was politically ambitious. In 1944 FDR wanted Douglas as his vice presidential running mate after he had dumped Henry Wallace, but party bosses persuaded the president to pick the less controversial Harry S. Truman. Four years later, Truman offered Douglas the vice presidential nomination, but Douglas turned it down, telling friends that he did not want to be “second fiddle to a second fiddle.”

Douglas remained on the Court and over time became its strongest First Amendment advocate, insisting that the US Constitution’s wording that “no law” shall restrict freedom of speech should be interpreted literally. This was particularly courageous during the hysteria of the Red Scare. In Terminiello v. Chicago (1949), Douglas’s opinion reversed Chicago’s “breach of peace” ordinance, which banned speech that “stirs the public to anger, invites dispute, brings about a condition of unrest, or creates a disturbance.” To hold otherwise, he wrote, “would lead to standardization of ideas either by legislatures, courts, or dominant political or community groups.” Douglas wrote a spirited dissent in Dennis v. United States (1951), which upheld the convictions of American Communist Party members for conspiracy to teach and advocate overthrow of the government.

In 1953 Douglas granted a temporary stay of execution to Julius and Ethel Rosenberg, convicted of being Soviet spies who sold the Soviet Union the plans for the atomic bomb. He ruled that they had been condemned to die by Judge Irving Kaufman without the consent of the jury, a violation of the Atomic Secrets Act. At the request of the Eisenhower administration, Chief Justice Fred Vinson took the unusual step of reconvening the Court—sending jets around the country to bring the justices back to Washington—in order to set aside Douglas’s stay. As a result of Douglas’s action on the Rosenberg case, conservatives in Congress sought to impeach him, but the effort went nowhere.

Conservatives tried to impeach him again in 1970, at the behest of President Richard Nixon. According to Nixon aide John Ehrlichman, “From the beginning Nixon was interested in getting rid of William O. Douglas; Douglas was the liberal ideologue who personified everything that was wrong with the Warren Court.”

Nixon told then-congressman Gerald Ford to instigate impeachment proceedings for Douglas on several grounds—everything from writing articles for sexually explicit magazines to publishing Points of Rebellion (1969), in which he urged the nation’s young people to revolt against the establishment, to having connections with Albert Parvin, a Los Angeles businessman who asked Douglas to serve as president of his philanthropic foundation and who supposedly was connected to mob gambling interests in Las Vegas. The effort fizzled in part because a Democratic-led Congress refused to take it up and in part because Douglas was well prepared to defend himself.

On the bench he was a staunch advocate of women’s rights. In 1942, in Skinner v. State of Oklahoma, Douglas argued in his majority opinion that states could not impose compulsory sterilization as a punishment for a crime. Twenty-three years later, in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), Douglas wrote his most famous opinion. It overturned a Connecticut law that prohibited the use of contraceptives, arguing that it violated the “right to marital privacy.” Douglas’s “right to privacy” opinion laid the groundwork for Roe v. Wade (1973), giving women the right to an abortion.

Douglas was a lifelong outdoorsman and nature lover. In 1960, two years before Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring was published, he wrote a dissenting opinion in support of a small group of Long Islanders who were trying to block the spraying of DDT. In 1972, when the Court refused to let the Sierra Club sue over the Walt Disney Corporation’s plan to build a resort next to Sequoia National Park, on the basis that the conservation group lacked legal standing, Douglas strenuously disagreed. In his dissent in Sierra Club v. Morton, he noted that if ships and corporations had standing, then so too should “valleys, alpine meadows, rivers, lakes, estuaries, beaches, ridges, groves of trees, swampland or even air.” It would take five more years, but the Sierra Club eventually blocked the project. In 1976 the Sierra Club made Douglas an honorary vice president, calling him “the highest-placed advocate of wilderness in the United States.”

Even Douglas’s strongest supporters acknowledged that his opinions were often written hastily, that his personal life was a mess (he married four times), and that he never got over the disappointment of not being president, a position he thought he deserved. But Douglas’s enduring legacy, as one of his biographers, L. A. Powe Jr., observed, is that “even in the worst of times judges can actually stand up and demand we adhere to our ideals.”