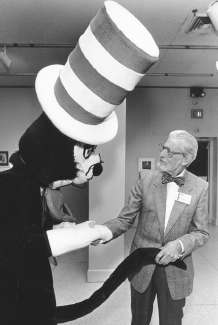

CREDIT: Associated Press/Burt Steel

WRITING UNDER the pen name “Dr. Seuss,” Theodor Geisel was, and remains two decades after his death, the world’s most popular writer of modern children’s books. He wrote and illustrated forty-four children’s books, characterized by memorable rhymes, whimsical characters, and exuberant drawings that have encouraged generations of children to love reading and expand their vocabularies. His books have been translated into more than fifteen languages and have sold over 200 million copies. They have been adapted into feature films, TV specials, and a Broadway musical. He earned two Academy Awards, two Emmy Awards, a Peabody Award, and the Pulitzer Prize.

Despite his popular image as a kindly cartoonist for kids, Geisel was also a moralist and political progressive whose views suffuse his stories. Some of his books use ridicule, satire, wordplay, nonsense words, and wild drawings to take aim at bullies, hypocrites, and demagogues. He believed that children’s books should be both entertaining and educational. He thought that writers of children’s books should “talk, not down to [children] as kiddies, but talk to them clearly and honestly as equals.”

Geisel grew up in Springfield, Massachusetts. In 1925 he graduated from Dartmouth College, where he served as editor in chief of the campus humor magazine. He soon found some success submitting humorous articles and illustrations to different magazines, including Judge, the Saturday Evening Post, Life, Vanity Fair, and Liberty, writing as Dr. Seuss.

Geisel’s work as a children’s author began by accident. In 1931 an editor at Viking Press called Geisel—at the time a successful advertising illustrator—and offered him a contract to illustrate a book of children’s sayings, Boners. The book sold well, and soon Geisel produced a sequel. Five years later, returning from Europe on a ship in rough waters and facing gale-force winds, Geisel began reciting words to the chugging rhythm of the ship’s engines. He began saying, “And that is a story that no one can beat, and to think that I saw it on Mulberry Street,” the name of a major thoroughfare in his hometown of Springfield. When he got back to New York, Geisel began writing and drawing a book that became And to Think That I Saw It on Mulberry Street. Twenty-nine publishers rejected the book, in part because children’s books in verse were out of style. Finally, in 1937, Geisel found a publisher for the book. It earned good reviews, especially for its illustrations, but sold poorly, as did his next several children’s books.

Horton Hatches the Egg (1940) was more successful, winning praise for its imaginative rhymes and drawings and its funny story about an elephant and a bird. Horton might have given Geisel the commercial boost he was hoping for, but he was preoccupied by the war in Europe, Hitler’s persecution of the Jews, and America’s need to prepare itself for war. He put his children’s books on hold and became an editorial cartoonist for the left-wing New York City daily newspaper PM and then a wartime writer and illustrator for the US government and the military, helping make propaganda and training films to support the war effort.

Fervently pro–New Deal, PM included sections devoted to unions, women’s issues, and civil rights. Geisel sharpened his political views as well as his artistry and his gift for humor at PM, where, from 1941 to 1942, he drew over 400 cartoons. The tabloid paper “was against people who pushed other people around,” Geisel explained. “I liked that.”

His work viciously but humorously attacked Adolf Hitler and Benito Mussolini. He bluntly criticized isolationists who opposed American entry into the war, especially the famed aviator (and Hitler booster) Charles Lindbergh and right-wing radio priest Father Charles Coughlin, both of whom were anti-Semites, and Senator Gerald Nye of North Dakota, an isolationist leader. Geisel’s was one of the few editorial voices to decry the US military’s racial segregation policies. He used his cartoons to challenge racism at home against Jews and blacks, union-busting, and corporate greed, which he thought divided the country and hurt the war effort. But Geisel also got swept up by the country’s anti-Japanese hysteria and drew several cartoons, using racist caricatures of Japanese people, depicting Japanese Americans as traitors to the United States.

Many Dr. Seuss books are about the misuse of power—by despots, kings, or other rulers, including parents who arbitrarily wield authority. In a university lecture in 1947—a decade before the modern civil rights movement—Geisel urged would-be writers to avoid the racist stereotypes common in children’s books and opined that America “preaches equality but doesn’t always practice it.” His children’s books consistently reveal his sympathy with the weak and the powerless and his fury against bullies and tyrants. His books teach children to think about how to deal with an unfair world. Rather than telling them what to do, Geisel invites his young readers to consider what they should do when faced with injustice.

After the war, he occasionally submitted cartoons to publications. One 1947 drawing, published in the New Republic, depicts Uncle Sam looking in horror at Americans accusing each other of being Communists. It was a clear statement of Geisel’s anger at the nation’s right-wing hysteria. But Geisel devoted most of his postwar career to writing children’s books and quickly became a well-known and commercially successful author—thanks in part to the postwar baby boom. He was popular with parents, kids, and critics alike. First came If I Ran the Zoo (1950) and Scrambled Eggs Super! (1953).

Next came Horton Hears a Who! (1954), the first of Geisel’s politically oriented children’s books, written during the McCarthy era. It features Horton the Elephant, who befriends tiny creatures (the “Whos”) whom he cannot see but whom he can hear thanks to his large ears. Horton rallies his neighbors to protect the endangered Who community. Horton observes in one of Geisel’s most famous lines: “Even though you can’t see or hear them at all, a person’s a person, no matter how small.” The other animals ridicule Horton for believing in something that they cannot see or hear, but he remains loyal to the Whos. Horton urges the Whos to join together to make a big enough sound so that the jungle animals can hear them. That can only happen, however, if Jo-Jo, the “smallest of all” the Whos, speaks out to save the entire community. Eventually he does so, and the Whos survive. Some Seuss analysts see the book as a parable about protecting the rights of minorities, urging “big” people to resist bigotry and indifference toward “small” people, and the importance of individuals’ (particularly “small” ones) speaking out against injustice. Other observers, however, view the residents of Who-ville as representing the Japanese people. Despite Geisel’s racist caricatures of the Japanese during the war, he was horrified by the consequences of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima and came to sympathize with the helplessness of the Japanese when he visited the country after the war. His changing attitude is evident in Horton Hears a Who!, which Geisel dedicated to a Japanese friend. In the book, Horton represents the US government’s effort to rebuild Japan as a democracy. (“I’ve got to protect them,” Horton says, “I’m bigger than they.”) Other jungle animals in the story oppose this effort, preferring revenge or indifference—much like many Americans at the time.

Geisel next wrote his most famous book, The Cat in the Hat, in response to a challenge. In May 1954 Life magazine published an article about widespread illiteracy among schoolchildren, claiming that they were not learning to read because their books were boring. William Spaulding, an editor at Houghton Mifflin, asked Geisel to write a book using the 225 words that he believed all first-graders should be able to recognize. Spaulding challenged Geisel to “bring back a book children can’t put down.” Within nine months, Geisel produced The Cat in the Hat. It was an immediate success. The book became the first in a series of Dr. Seuss’s Beginner Books that combined a simple vocabulary, wonderful drawings, imaginative stories, and bizarre characters (many based on animals). In quick succession, he wrote On Beyond Zebra! (1955), If I Ran the Circus (1956), How the Grinch Stole Christmas (1957) and Green Eggs and Ham (1960), which used only fifty words.

In several early books—including The 500 Hats of Bartholomew Cubbins (1938), The King’s Stilts (1939), and Bartholomew and the Oobleck (1949)—Geisel makes fun of the pretensions, foolishness, and arbitrary power of kings. His finest rendition of this theme is Yertle the Turtle (1958). Yertle, king of the pond, stands atop his subjects in order to reach higher than the moon, indifferent to the suffering of those beneath him. In order to be “ruler of all that I see,” Yertle stacks up his subjects so he can reach higher and higher. Mack, the turtle at the very bottom of the pile, says,

I don’t like to complain,

But down here below, we are feeling great pain.

I know, up on top you are seeing great sights,

But down at the bottom we, too, should have rights.

Yertle tells Mack to shut up. Frustrated and angry, Mack burps, shaking the carefully piled turtles, and Yertle falls into the mud. His rule ends and the turtles celebrate their freedom. The story is clearly about Hitler’s thirst for power, a topic that inspired some of Geisel’s most powerful PM cartoons But Geisel is also saying that ordinary people can overthrow unjust rulers if they understand how to use their own power. The story’s final lines reflect Geisel’s political outlook:

And the turtles, of course . . . all the turtles are free

As turtles and, maybe, all creatures should be.

The Sneetches (1961), inspired by the Protestant Geisel’s opposition to anti-Semitism, exposes the absurdity of racial and religious bigotry. Sneetches are yellow birdlike creatures. Some Sneetches have a green star on their belly. They are the “in” crowd and they look down on Sneetches who lack a green star, who are the outcasts. Eventually, they all realize that neither the plain-belly nor star-belly Sneetch is superior. The story is an obvious allegory about racism and discrimination, clearly inspired by the yellow stars that the Nazis required Jews to wear on their clothing to identify them as Jewish.

The Lorax (1971) appeared as the environmental movement was just emerging, less than a year after the first Earth Day. Geisel called it “straight propaganda”—a polemic against pollution—but it also contains some of Geisel’s most creative made-up words, like “cruffulous croak” and “smogulous smoke.” A small boy listens to the Once-ler tell the story of how the area was once full of Truffula trees and Bar-ba-loots and was home to the Lorax. But the greedy Once-ler—clearly a symbol of business—cuts down all the trees to make thneeds, which “everyone, everyone, everyone needs.” The lakes and the air become polluted, there is no food for the animals, and it becomes an unlivable place. The Once-ler only cares about making more things and more money, ignoring warnings about the devastation he’s causing.

he says. Eventually the Once-ler shows some remorse, telling the boy:

Unless someone like you

cares a whole awful lot

nothing is going to get better

It’s not.

The book attacks corporate greed and excessive consumerism, themes that remind some readers of How the Grinch Stole Christmas. The Lorax was once banned by a California school district because of its obvious opposition to clear-cutting by the powerful logging industry.

In 1984 Geisel produced The Butter Battle Book, another strong statement about a pending catastrophe—the nuclear arms race between the United States and the Soviet Union, while Ronald Reagan was president. “I’m not anti-military,” Geisel told a friend at the time, “I’m just anti-crazy.” It is a parable about the dangers of the political strategy of “mutually assured destruction” brought on by the escalation of nuclear weapons. Geisel’s satirical gifts are on display. The cause of the senseless war is a trivial conflict over toast. The battle is between the Yooks and the Zooks, who do not realize that they are more alike than different, because they live on opposite sides of a long wall. They compete to make bigger and better weapons until both sides invent a destructive bomb (the “Bitsy Big-Boy Boomeroo”) that, if used, will kill both sides. Like The Lorax, there is no happy ending or resolution. As the story ends, the generals on both sides of the wall are poised to drop their bombs. It is hard for even the youngest reader to miss Geisel’s point.