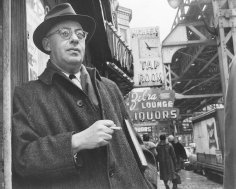

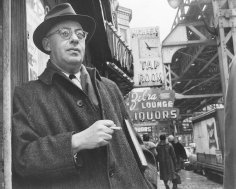

CREDIT: Associated Press

AFTER RIOTS erupted in the Rochester, New York, ghetto in the summer of 1964, an interracial group of clergy approached organizer Saul Alinsky to help them build a power base among low-income African Americans and challenge the influence of the city’s dominant employer, Eastman Kodak, which employed only 750 blacks out of 40,000 employees. (Alinsky quipped that “the only thing Kodak has done on the race issue in America is to introduce color film.”) After several months of meetings, local residents founded Freedom, Integration, God, Honor, Today (FIGHT), a community organizing group, to take on Kodak. But after the company refused to create a training and hiring program for black residents, FIGHT upped the ante. A number of FIGHT members and their churches purchased Kodak stock and pledged to attend the company’s annual shareholder meeting. Kodak tried to keep protesters at a distance by holding the meeting in New Jersey, but FIGHT brought a thousand people to the meeting 600 miles away. Their action gained national media attention.

Following this, Alinsky threatened to bring 100 black people to a Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra concert after treating them to a banquet of nothing but huge portions of baked beans. The idea was to conduct the nation’s first “fart-in” to embarrass Kodak, a major Philharmonic sponsor. Fortunately for the Philharmonic, FIGHT did not have to resort to that tactic, because Kodak agreed to implement the jobs program.

The battle in Rochester was typical of Alinsky’s approach, which was to employ any tactic that would work to bring powerful politicians and corporations to the negotiating table with ordinary people. As he wrote in his 1971 book Rules for Radicals, “The Prince was written by Machiavelli for the Haves on how to hold power. Rules for Radicals is written for the Have-Nots on how to take it away.”

Alinsky reshaped activism and politics in America by transferring some of the tactics of grassroots organizing from shop floors and factories to urban neighborhoods and congregations. Alinsky was widely known in the 1960s as an “agitator” and a “troublemaker,” but his fame had faded somewhat (except among progressive activists) until 2008, when Republicans revived his reputation by linking Alinsky to both the major Democratic Party candidates for president. In the late 1960s Hillary Clinton had spent time with Alinsky and had written her senior thesis at Wellesley College about him. Conservatives mined her report to uncover flattering comments about Alinsky in order to tarnish her as a radical.

But the GOP honchos took even larger swipes at Barack Obama, who had been a community organizer for three years in Chicago and had acknowledged being influenced by Alinsky’s writings and ideas. In her September 2008 speech accepting the GOP vice presidential nomination at the Republican convention in St. Paul, Alaska governor Sarah Palin said, “I guess a small-town mayor is sort of like a community organizer, except that you have actual responsibilities.” A few days later, former New York mayor Rudy Giuliani sought to link Obama with what he called “a very core Saul Alinsky kind of almost socialist notion that [government] should be used for redistribution of wealth.”

Giuliani was both wrong and right. Obama was not recruited by Alinsky’s community organizing group (the Industrial Areas Foundation) but by another church-based group engaged in organizing in Chicago’s poor neighborhoods. But he was right about Alinsky’s outlook. Alinsky did believe in the “redistribution of wealth,” although he never called himself a Socialist.

Alinsky was born to Orthodox Jewish parents in Chicago who divorced when he was thirteen. Over time Alinsky increasingly took after his firebrand mother.

At the University of Chicago, Alinsky took courses in the school’s famed sociology department and then attended graduate courses in criminology and a few law school courses. Leaving graduate school without a degree, Alinsky joined Chicago’s Institute for Juvenile Research (IJR), which was developing community projects based on the then-novel theory that crime was the result of poverty and social turmoil in neighborhoods. Alinsky developed a talent for building trusting relationships with community residents, criminals, and prisoners.

In 1938 IJR assigned Alinsky to study Chicago’s Back of the Yards area, the immigrant neighborhood of about 90,000 residents made famous in Upton Sinclair’s The Jungle. Alinsky spent most of his time with leaders of the Packinghouse Workers union, who were trying to organize the employees of the major meatpacking firms that dominated the area. The union understood that it would be difficult to win a victory in the workplaces without community support, so they embraced Alinsky’s efforts to build a neighborhood organization.

In Back of the Yards, Alinsky sought out local leaders involved in churches, sports leagues, neighborhood businesses, and other networks. One was Joseph Meegan. He and Alinsky gained the confidence of Chicago’s auxiliary Catholic bishop Bernard Sheil, who helped them recruit young priests and parish leaders and overcome the tensions between Catholics from different ethnic backgrounds. They persuaded Sheil to speak at the 1939 founding meeting of the Back of the Yards Neighborhood Council (BYNC), where about seventy-five organizations were represented. The next day, Sheil shared the stage with Congress of Industrial Organizations president John L. Lewis at a rally of 10,000 people.

The alliance between the church and the union guaranteed that the BYNC would be taken seriously by the city’s political and corporate power brokers. The BYNC put pressure on city officials to provide the neighborhood with school lunch and milk programs, fluoridated drinking water, an infant-health clinic, and a baseball field with floodlights. The BYNC got the city to spray weed killer in vacant lots, and it sold garbage cans to the community at a fraction of the market cost. It started a credit union to provide local residents and businesses with low-interest loans. It pressured the Works Progress Administration and the National Youth Administration to provide jobs for neighborhood residents. Its success marked the beginning of modern community organizing.

This success caught the attention of some important patrons. Bishop Sheil and Marshall Field III (newspaper publisher and heir to the Marshall Field family fortune) helped fund Alinsky’s new organization, the Industrial Areas Foundation (IAF), designed to train community organizers and to build community organizations in other cities. In 1946 Alinsky published Reveille for Radicals describing the nuts and bolts of effective organizing. The book became the bible of community organizing until he wrote Rules for Radicals in 1971.

These books have not only provided organizers with a tool kit of principles and tactics but have also offered a vision for a renewed democracy. In Alinsky’s view, an empowered citizen actively questions the decisions made by those in power. Alinsky was scornful of social workers, whom he thought viewed poor people as “clients” to be served by beneficent experts. He felt similarly about government antipoverty programs, which he called “political pornography,” because he believed they distributed crumbs that kept people pacified. The organizer’s job was to agitate people to recognize their own self-interest and then to help them mobilize to gain a stronger voice in challenging the bastions of power and privilege. Organizers, he thought, have to show people that many problems they view as personal troubles can only be addressed through collective action. Alinsky taught that confrontation and conflict were necessary to change power relations.

One way to achieve that, Alinsky believed, was to “personalize” an issue—to identify the person in government, a corporation, or another institution who has the power and authority to make a decision that will change its practices. Alinsky believed it was necessary to “rub raw the resentments of the people in the community.” That meant getting people involved in small-scale battles (against unscrupulous merchants or realtors, for example) so they could experience winning, gain self-confidence, and then tackle larger targets and issues. Community organizing, he believed, taught people how to win concrete victories, and to do so through creative tactics that were fun and morale-building. He realized that compromise was the heart of democracy. It was about sharing power.

Alinsky viewed his success in Chicago as a first step in building a network of “people’s organizations” around the country. These community groups, along with unions, would form the basis of a progressive movement for social justice. In 1947 Alinsky hired Fred Ross, an experienced organizer among California’s migrant farmworkers. Ross built the Community Service Organization (CSO) in several cities, mostly among Latinos, recruiting new members and identifying potential leaders through house meetings and one-on-one conversations. In San Jose, California, one of the people Ross recruited was Cesar Chavez, who began as a leader but whom Ross soon hired and trained as an organizer. Chavez would later adopt these organizing ideas in starting the United Farm Workers union.

In the mid-1960s Alinsky began training organizers and overseeing campaigns in Rochester and Buffalo, New York; St. Paul, Minnesota; New York City; Kansas City, Missouri; and Chicago. Alinsky worked closely with African American groups in major cities, hoping to build stable organizations that could battle segregation and wield influence on a variety of issues. But he was not involved in the southern civil rights movement, whose leaders did not seek his advice. Alinsky was particularly scornful of the student New Left and the campus antiwar movement. He did not think they understood the importance of building organizations with leaders and relied too much on protests, demonstrations, and media celebrities. He considered their sometimes revolutionary rhetoric silly, utopian, and dogmatic.

Alinsky’s ideas took hold and influenced organizers and activists around the country. His books and colorful campaigns brought him a great deal of attention (including a glowing profile in Time magazine in 1970), and he became an iconic figure among organizers.

Beginning in the 1970s, America experienced an upsurge of community organizing, what writer Harry Boyte called a “backyard revolution.” Many community groups emerged and adopted Alinsky’s ideas. They organized around slum housing and tenants’ rights, public safety, and racial discrimination by banks (redlining), achieving some success. Environmental groups drew on Alinsky’s ideas, especially those opposed to the construction of nuclear power plants or those fighting the toxic takeover of their neighborhoods, such as the battle in the polluted Love Canal neighborhood in Niagara Falls, New York.

Whereas Alinsky focused almost entirely on building neighborhood-based organizations, since his death in 1972, a number of national organizing networks with local affiliates have emerged, enabling groups to address problems at the local, state, and national levels, sometimes even simultaneously. These include the National Welfare Rights Organization, ACORN, National People’s Action, PICO, Direct Action Research and Training (DART), and Gamaliel. In addition, veteran activists have created a number of training centers—including the Midwest Academy, Grassroots Leadership, the Center for Third World Organizing, the Green Corps, the AFL-CIO Organizing Institute, and the Organizing and Leadership Training Center—to nurture new generations of social change organizers.

Tens of thousands of organizers and activists have been directly or indirectly influenced by Alinsky’s ideas about organizing. Most of them have been progressives, following Alinsky’s instincts to challenge the rich and powerful. But the left has no monopoly on using Alinsky’s techniques. After Obama took office in 2009, conservatives like Glenn Beck and the Tea Party both attacked Obama for being an Alinsky-ite and a “socialist,” and they began recommending Alinsky’s books as training tools for building a right-wing movement. One Tea Party leader explained, “Alinsky’s book is important because there really is no equivalent book for conservatives. There’s no ‘Rules for Counter-Radicals.’” Freedom Works, a corporate-funded conservative group started by former Republican congressman Dick Armey, uses Rules for Radicals as a primer for its training of Tea Party activists.