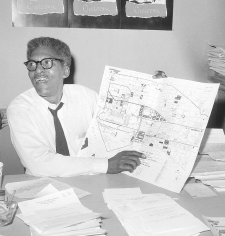

CREDIT: Associated Press

BAYARD RUSTIN was black, gay, a pacifist, and a radical, and thus had four strikes against him in terms of influencing mainstream America. But from the 1940s through the 1960s, he managed to use his immense talents—as an organizer, strategist, speaker, intellectual, and writer—to effectively challenge the economic and racial status quo. Always an outsider, he helped catalyze the civil rights movement with courageous acts of resistance. He was the lead organizer of the 1963 March on Washington, a job for which it seemed he had prepared his entire life.

The youngest of eight children, Rustin was raised by his grandparents in West Chester, Pennsylvania. His grandmother was a Quaker and an early member of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Rustin was a gifted student, an outstanding football and track athlete, and an exceptional tenor. In high school he was arrested for refusing to sit in the local movie theater’s balcony, which was nicknamed “Nigger Heaven.” He attended two black colleges and then moved to New York City in 1937. He enrolled briefly at the City College of New York, where he got involved with the campus Young Communist League. He was attracted by their antiracist efforts—including their fight against segregation in the military—but he broke with the Communist Party after a few years.

While singing in nightclubs to earn money, Rustin looked for other ways to channel his prodigious energy, his outrage against racism, and his growing talent as an organizer. He found two mentors who shaped his thinking and employed him as an organizer, A. Philip Randolph and A. J. Muste. Randolph hired Rustin in 1941 to lead the youth wing of the March on Washington movement, designed to push Franklin D. Roosevelt to open up defense jobs to black workers as the United States geared up for World War II.

Then, under Muste’s guidance, Rustin began a series of organizing jobs with several pacifist groups—the Fellowship of Reconciliation (FOR), the American Friends Service Committee, and the War Resisters League. These were small, mostly white organizations that provided Rustin with a home base. A brilliant, charismatic speaker, Rustin kept up a hectic travel schedule, preaching the gospel of nonviolence and civil disobedience on campuses, in churches, and at meetings of fellow pacifists.

In 1942 Rustin recruited a nucleus of militants to form the Congress of Racial Equality, committed to using Gandhian tactics to dismantle segregation. Rustin trained and led small groups engaged in nonviolent protests to integrate restaurants, movie theaters, barber shops, amusement parks, and department stores. That year, he was beaten by a policeman in Tennessee for refusing to move to the rear of a segregated bus. In this and subsequent actions, Rustin showed enormous courage, believing that a few people, acting as witnesses for justice, could trigger a broader mass movement—a prophecy he helped fulfill in the 1960s.

As a Quaker and conscientious objector, Rustin was legally entitled to do alternative service rather than military service during World War II, but on principle, objecting to war in general and the segregation of the armed forces in particular, he refused to serve even in the Civilian Public Service. In 1944 he was convicted of violating the Selective Service Act and was sentenced to three years in a federal prison in Kentucky.

Upon his release, he rejoined the Fellowship of Reconciliation and resumed his career as a peripatetic organizer. In April 1947 he led FOR’s interracial Journey of Reconciliation, bold nonviolent acts of civil disobedience through four southern and border states to challenge segregation and a precursor to the Freedom Rides of the early 1960s. He and others were arrested in Chapel Hill, North Carolina, and Rustin spent twenty-two days on a prison camp chain gang.

In 1948 Rustin went back to work for Randolph to push President Harry S. Truman to enforce and expand FDR’s antidiscrimination order. They organized protests in several cities and at the 1948 Democratic Party national convention. Their hard work paid off: Truman desegregated the military and outlawed racial discrimination in the federal civil service that year.

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, while still on FOR’s staff, Rustin visited India, Africa, and Europe, making contact with activists in the various independence and peace movements. Increasingly, he viewed the struggle for civil rights in the United States as part of a worldwide movement against war and colonialism.

In 1953 Rustin was arrested for “public indecency”—having homosexual sex in a parked car—in Pasadena, California, where he had been invited to give a talk. Although Rustin was unusually open among his friends about his homosexuality, this was the first time that it had come to the public’s attention. Homosexual behavior was a crime in every state. A. J. Muste fired him for jeopardizing FOR’s already controversial reputation. But Randolph got him a similar job with the War Resisters League, where Rustin worked for the next twelve years.

During the next decade, Rustin played a critical but behind-the-scenes role as a key organizer within the civil rights movement. At Randolph’s behest, he went to Montgomery, Alabama, in 1955 to help with the bus boycott. Rustin helped local leaders with advice on organizing a large-scale boycott, but his biggest influence was mentoring Martin Luther King Jr., who had no practical organizing experience, on the philosophy and tactics of civil disobedience.

But much of that advice would be given from a distance, in phone calls, memos, and drafts of ghostwritten articles and book chapters for King. Rustin had to cut short his first visit to Montgomery because, as a former Communist and as a gay man, he was a political liability. So just at the moment when Rustin might have helped lead the mass movement that he had been working for his entire adult life, he had to do so quietly and in the shadows.

At the end of 1956, the Supreme Court ruled that Montgomery’s segregated bus system was unlawful. The victory could have remained a local triumph rather than a national bellwether. Rustin, however, along with Ella Baker and Stanley Levinson (another King adviser), laid out the idea for building what Rustin called a “mass movement across the South” with “disciplined groups prepared to act as ‘nonviolent shock troops.’” This was the genesis of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, which catapulted King from local to national leadership. Baker was hired to build the organization, and Rustin became King’s strategist, ghostwriter, and link to northern liberals and unions.

In 1963 Randolph pulled together the leaders of the major civil rights, labor, and liberal religious organizations and laid out his idea for a major march on Washington to push for federal legislation—particularly for the Civil Rights Act, which Kennedy had proposed but which was stalled in Congress. Kennedy tried to dissuade the leaders from sponsoring the march, contending that it would undermine support for the Civil Rights bill. But Randolph had faced down presidents before, and he did so again. Over the opposition of some civil rights leaders, Randolph insisted that Rustin serve as the day-to-day organizer of the March for Jobs and Freedom. Rustin pulled together a staff and organized all the logistics.

Three weeks before the march, Senator Strom Thurmond, a South Carolina segregationist, publicly attacked Rustin on the floor of the Senate by reading reports of his Pasadena arrest for homosexual behavior a decade earlier—documents he probably got from FBI director J. Edgar Hoover. Randolph defended Rustin’s integrity and his role in the march, but, as John D’Emilio, Rustin’s biographer, noted, thanks to Thurmond, “Rustin had become perhaps the most visible homosexual in America.”

After the triumphant march, Rustin continued organizing within the civil rights, peace, and labor movements. In February 1964 he coordinated a one-day school boycott in New York City to protest the slow progress of school integration. On that day, 464,000 pupils stayed away from school. King continued to rely on Rustin’s advice, but always from a safe distance, fearful the movement would be tarnished by the controversial Rustin.

After Congress passed the Voting Rights Act in 1965, Rustin—who had spent his entire life stirring up protests—wrote a much-read and controversial article, “From Protest to Politics,” in the then-liberal magazine Commentary, arguing that the coalition that had come together for the March on Washington needed to place less emphasis on protest and instead focus on electing liberal Democrats who could enact a progressive policy agenda centered on full employment, housing, and civil rights. Rustin drafted a “Freedom Budget,” released in 1967, that advocated “redistribution of wealth.” Rustin’s ideas influenced King, who increasingly began to talk about the importance of jobs and economic redistribution.

However, Rustin’s ideas were controversial among the young Student Non-violent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) radicals, who did not trust unions or the Democratic Party. SNCC had become a key advocate of “black power,” an idea that Rustin opposed because it undermined his belief in coalition politics and racial integration.

But the two biggest obstacles to Rustin’s program were the war in Vietnam, which drained resources and attention away from Lyndon B. Johnson’s Great Society and War on Poverty, and the urban riots that began in 1965 in Los Angeles and triggered a backlash against the civil rights movement. Rustin was among the first public figures to call for the withdrawal of all American forces from South Vietnam, but as LBJ escalated the war, Rustin muted his criticisms. He wanted to avoid alienating LBJ, Democratic leaders, and union leaders who supported the war and who funded the A. Philip Randolph Institute, which had been created in 1964 to provide Rustin with an organizational home. When King announced his strong opposition to the war in 1967, it caused a serious rift between the two men. As a result, Rustin—one of the nation’s most important and courageous pacifists for three decades—was absent from the antiwar movement and lost credibility among many New Left student activists.

Rustin devoted much of the last two decades of his life to working on international human rights. He traveled around the globe, monitoring elections and the status of human rights in Chile, El Salvador, Grenada, Haiti, Poland, Zimbabwe, and elsewhere.

Ironically, Rustin’s homosexuality—which had limited his activist career for decades—became a centerpiece of his last few years. Rustin did not initially embrace the burgeoning gay rights movement, which exploded after the Stonewall riot in New York City in 1969. He only began to speak publicly about the importance of civil rights for gays and lesbians during his last few years, when he was involved in a stable relationship. Thanks in part to a 2003 documentary about Rustin, Brother Outsider, he has become something of an icon among gay activists.