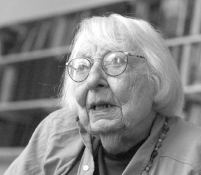

CREDIT: Associated Press/CP files, Adrian Wyld

ON APRIL 10, 1968, New York state officials scheduled a public hearing to discuss their plans for an expressway that would have sliced across Lower Manhattan and displaced hundreds of businesses and the homes of 2,000 families. The expressway’s opponents, including Jane Jacobs, a writer who lived in Greenwich Village, considered the hearing a sham. Jacobs noticed that the microphone was set up so that speakers addressed the crowd, not the transportation officials seated on the stage. When speakers asked the officials questions about the project, they refused to answer, saying that they were just there to listen.

When it was Jacobs’s turn to speak, she gave a blistering critique of the highway plan. Then she announced that she was going to walk up on the stage and march past the officials’ table in silent protest, and she welcomed others to join her. About fifty people followed Jacobs to the stage. “You can’t come up here,” the top state official said. “Get off the stage.” Jacobs refused, so the official summoned the police and shouted, “Arrest this woman.”

Jacobs was taken to the police station and released, promising to appear in court. The next day, and for several days afterwards, her arrest was headline news. When she appeared in court on April 17, the city had changed the charges from disorderly conduct to second-degree riot, inciting a riot, criminal mischief, and obstructing public administration, all more serious criminal charges. She was told that she faced anywhere from fifteen days to one year in prison for each charge. Many of New York’s leading liberals came to Jacobs’s defense, offering to create a legal defense fund and writing letters and articles protesting her treatment. The charges were eventually dropped.

This was one battle in a much longer war that Jacobs had waged against top-down city planning, particularly as practiced by New York’s planning and public works czar, Robert Moses. Moses was a master builder who for decades had reshaped the physical landscape of New York City and its suburbs, bulldozing entire neighborhoods, constructing highways, bridges, parks, beaches, and housing projects, all oriented toward the car and away from public transit. From the 1940s through the 1960s, he was considered the most powerful individual in New York, even though he was never elected to any office.

But Moses met his match in Jacobs, whose only ammunition was her typewriter, her network of community activists, and her moral authority. The controversy surrounding Jacobs’s arrest led New York Mayor John Lindsay to cancel the highway project. It was also the beginning of Moses’s fall from power: Governor Nelson Rockefeller removed him from his positions as head of several powerful agencies. More importantly, Jacobs’s victory over the expressway marked a triumph for a different view of city planning, one that she had been advocating for years, most prominently in her 1961 book The Death and Life of Great American Cities.

The book became the manifesto of a movement, much like Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring (1962), Betty Friedan’s The Feminine Mystique (1963), and Ralph Nader’s Unsafe at Any Speed (1965). Jacobs’s book and her subsequent writings changed the way we think about livable cities. Her views have become part of the conventional wisdom of city planning.

Jacobs grew up in Scranton, Pennsylvania. Graduating from high school during the Depression, she decided to get a job rather than go to college. In 1934 she moved to New York, where she found work as a secretary in Greenwich Village. She sold a series of articles about different areas of the city—such as the flower market and the diamond district—to Vogue magazine, earning $40 for each at a time when she was making $12 a week as a secretary. In her spare time, she took courses at Columbia University’s School of General Studies in geology, zoology, law, political science, and economics.

In 1952 Architectural Forum hired Jacobs as an editor, a position she held for ten years. It was there that her writings about city planning first got attention.

The 1950s was the heyday of urban renewal, the federal program that sought to wipe out urban blight with the bulldozer. Its advocates were typically downtown businesses, developers, banks, major daily newspapers, big-city mayors, and construction unions. Most planners and architects of the time joined the urban renewal chorus, convinced that big development projects would revitalize downtown business districts, stem the exodus of middle-class families to suburbs, and improve the quality of public spaces. On an assignment in Philadelphia, however, Jacobs noticed that the streets within an urban renewal project were deserted, whereas an older street nearby was crowded with people. She talked to the project architect, who described its wonderful aesthetics but seemed unconcerned with its impact on real people. Her impression was reinforced by a walking tour of East Harlem and other neighborhoods, where she came to see that the dominant ideas of city planning—bulldozing low-rise housing in poor neighborhoods and replacing it with tall apartment buildings surrounded by open space—were misguided. Planners preferred straight lines, big blocks, and order, but cities came alive when they brought out the human qualities of randomness, surprise, and social interaction.

In 1958 William Whyte, an editor at Fortune magazine, asked Jacobs to write an article on downtowns. The theme of the Fortune article became the manifesto of her book Death and Life, which she completed three years later: “Designing a dream city is easy. Rebuilding a living one takes imagination.”

“This book is an attack on current city planning and rebuilding,” she wrote in the book’s opening paragraph. “It is also, and mostly, an attempt to introduce new principles of city planning and rebuilding, different and even opposite from those now taught in everything from schools of architecture and planning to Sunday supplements and women’s magazines.”

Jacobs’s views about cities drew on her experiences living in Greenwich Village, which she considered the quintessential livable neighborhood. In 1947 she and her husband, an architect, bought a dilapidated three-story building and spent years fixing it up. She rode her bicycle to and from work.

Cities, Jacobs believed, should be untidy, complex, and full of surprises. Good cities encourage social interaction at the street level. They favor foot traffic, bicycles, and public transit over cars. They get people talking to each other. Residential buildings should be low-rise and should have stoops and porches. Sidewalks and parks should have benches. Streets should be short and should wind around neighborhoods. Livable neighborhoods require mixed-use buildings—especially those with first-floor retail establishments and housing above. She saw how “eyes on the street” could make neighborhoods safe as well as supportive. She favored corner stores over big chains and liked newsstands and pocket parks where people can meet casually. Cities, she believed, should foster a mosaic of architectural styles and heights. And they should allow people from different income, ethnic, and racial groups to live in close proximity.

Jacobs was self-taught, with no college degree or credential. She was unencumbered by planning orthodoxy, although she carefully read and thoroughly critiqued the major thinkers in the field—including Sir Patrick Geddes, Ebenezer Howard, Le Corbusier, and Lewis Mumford—who believed that high-rise towers surrounded by open spaces reflected the best combination of technology, efficiency, and modernism. Likewise, she condemned the execution of these ideas by Moses and other government planners who arrogantly believed that their own expertise trumped the day-to-day experiences of the people whose lives were affected by their decisions.

Jacobs had a profound influence on both community organizers and planners. Her efforts in New York were part of a broader grassroots movement around the country to stop government agencies, typically with business support, from destroying poor and working-class communities—a process that activists often called “Negro removal.” From this cauldron emerged new leaders, new organizations, and new issues—issues such as bank redlining, tenants’ rights and rent control, neighborhood crime, environmental racism, and underfunded schools. Some groups that were founded to protest against top-down plans began thinking about what they were for, not just what they were against. Hundreds of community development corporations (CDCs) emerged out of these efforts.

Jacobs also paved the way for what became known as “advocacy planning.” Starting in the 1960s, a handful of urban planners and architects chose to side with residents of low-income urban neighborhoods against the power of city redevelopment agencies and their business allies. They provided technical skills (and sometimes political advice) for community groups engaged in trench warfare against displacement and gentrification. Jacobs’s activist work and her writings showed people they could defeat the urban renewal bulldozer. Eventually mayors and planning agencies began to rethink the bulldozer approach to urban renaissance. In 1974 President Richard Nixon canceled the urban renewal program.

Although many developers and elected officials still favor the top-down approach, most planners and architects have absorbed Jacobs’s lessons. Advocates of “smart growth” and “new urbanism” claim Jacobs’s mantle, although she would no doubt dispute some of their ideas and, in particular, criticize the failure of these approaches to make room for poor and working-class residents.

Jacobs wrote several other books—including The Economy of Cities (1969), and Cities and the Wealth of Nations (1984)—but none of them had the influence of Death and Life, which eventually became required reading in planning, architecture, and urban studies programs.

Hailed for her visionary writing and activism, Jacobs refused to accept sainthood. She turned down honorary degrees from more than thirty institutions. She always gave credit to the ordinary people on the front lines of the battle over the future of their neighborhoods and cities.