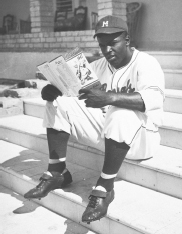

CREDIT: Associated Press

WHEN JACKIE Robinson took the field for the Brooklyn Dodgers on April 15, 1947, he was the first black player in modern major league baseball. A half century later, America celebrated the fiftieth anniversary of his courageous triumph over baseball’s apartheid system. Major League Baseball (MLB) honored Robinson by retiring his number—42—for all teams. President Bill Clinton appeared with Rachel Robinson at a Mets-Dodgers game at Shea Stadium to venerate her late husband. That year witnessed a proliferation of books, television movies, plays, symposia, museum exhibits, and academic conferences about Robinson. His hometown of Pasadena, California—which virtually ignored him during his own lifetime—finally got around to dedicating a Rose Bowl Parade in his honor.

Why so much activity to commemorate a baseball player? Because Robinson was and is more than a baseball icon. His success on the baseball diamond was a symbol of the promise of a racially integrated society. It is difficult today to summon the excitement and fervor that greeted Robinson’s achievement. He did more than change the way baseball is played and who plays it. His actions on and off the diamond helped pave the way for America to confront its racial hypocrisy. The dignity with which Robinson handled his encounters with racism among fellow players and fans—and in hotels, restaurants, trains, and other public places—drew public attention to the issue, stirred the consciences of many white Americans, and gave black Americans a tremendous boost of pride and self-confidence. Martin Luther King Jr. once told Dodgers pitcher Don Newcombe, “You’ll never know what you and Jackie and Roy [Campanella] did to make it possible to do my job.”

Robinson was one of America’s greatest all-around athletes. He was a four-sport star athlete at UCLA, played professional football, and then played briefly in baseball’s Negro Leagues. He spent his major league career (1947 to 1956) with the Brooklyn Dodgers and was chosen Rookie of the Year in 1947 and Most Valuable Player in 1949. An outstanding base runner, with a .311 lifetime batting average, he led the Dodgers to six pennants and was elected to the Hall of Fame in 1962.

The grandson of a slave and the son of a sharecropper, Robinson was fourteen months old in 1920 when his mother moved her five children from Cairo, Georgia, to Pasadena, a wealthy, conservative Los Angeles suburb. During Robinson’s youth, black residents, who represented a small proportion of the city’s population, were treated like second-class citizens. Blacks were allowed to swim in the municipal pool only on Tuesdays (the day the water was changed) and could use the YMCA only one day a week.

Robinson learned at an early age that athletic success did not guarantee social or political acceptance. When his older brother Mack returned from the 1936 Olympics in Berlin with a silver medal in track, he got no hero’s welcome. The only job the college-educated Mack would find was as a street sweeper and ditch digger.

Robinson’s Pasadena background and personal characteristics played a role in the decision by Dodgers general manager Branch Rickey to select him out of the Negro Leagues to break the sport’s color barrier. He knew that if the Robinson experiment failed, the cause of baseball integration would be set back for many years. He could have chosen other Negro League players with greater talent or more name recognition, but he wanted someone who could be, in today’s terms, a role model. Robinson was articulate and well educated. Although born in the segregated Deep South, he had lived among and formed friendships with whites in his Pasadena neighborhood.

Rickey knew that Robinson had a hot temper and strong political views. As an army officer in World War II, Robinson had been court-martialed (although he was later acquitted) for resisting bus segregation at Fort Hood, Texas. But Rickey calculated that Robinson could handle the emotional pressure while helping the Dodgers on the field. Robinson promised Rickey that he would not respond to the inevitable verbal barbs and even physical abuse.

Rickey could not count on the other team owners or most major league players (many of whom came from southern or small-town backgrounds) to support his plan. But the Robinson experiment succeeded—on the field and at the box office. Within a few years, most other major league teams hired black players, although it was not until 1959 when the last holdout, the Boston Red Sox, brought an African American onto the roster.

After Robinson had established himself as a superstar, Rickey gave him the green light to unleash his temper. On the field, he fought constantly with umpires and opposing players. Off the field, he was outspoken—in speeches, interviews, and his regular newspaper column—against racial injustice. He viewed his sports celebrity as a platform from which to challenge American racism. During his playing career, he was constantly criticized for being so frank about race relations in baseball and in society. Many sportswriters and most other players—including some of his fellow black players, content simply to be playing in the majors—considered Robinson too angry and vocal.

Robinson’s political views reflected the tensions of Cold War liberalism. In 1949 Rickey orchestrated Robinson’s appearance before the House Un-American Activities Committee so that he could publicly criticize Paul Robeson, who had stirred controversy by stating in a Paris speech that American blacks would not fight in a war with Russia. As expected, Robinson challenged Robeson’s patriotism. “I and other Americans of many races and faiths have too much invested in our country’s welfare for any of us to throw it away for a siren song sung in bass,” Robinson said.

But Robinson also seized the opportunity, a decade before the heyday of civil rights activism, to make an impassioned demand for social justice and racial integration. “I’m not fooled because I’ve had a chance open to very few Negro Americans,” Robinson said to Congress. The press focused on Robinson’s criticism of Robeson and virtually ignored his denunciation of American racism.

Shortly before his death, Robinson said he regretted his remarks about Robeson. “I have grown wiser and closer to the painful truth about America’s destructiveness,” he acknowledged. “And I do have an increased respect for Paul Robeson, who sacrificed himself, his career, and the wealth and comfort he once enjoyed because, I believe, he was sincerely trying to help his people.”

When Robinson retired from baseball, no team offered him a position as a coach, manager, or executive. He became an executive with the Chock Full o’Nuts restaurant chain and became an advocate for integrating corporate America. He lent his name and prestige to several business ventures, including a construction company and a black-owned bank in Harlem. He got involved in these business activities primarily to help address the shortage of affordable housing and the persistent redlining (lending discrimination against racial minorities) by white-owned banks. Both the construction company and the Harlem bank later fell on hard times and perhaps dimmed Robinson’s confidence in black capitalism as a strategy for racial integration.

Nevertheless, Robinson’s views led him into several controversial political alliances. In 1960 he initially supported Senator Hubert H. Humphrey’s campaign for president, but when John F. Kennedy won the Democratic Party nomination, Robinson shocked his black and liberal fans by endorsing and campaigning for Richard Nixon. He came to regret that support. He later worked as an aide to New York’s Governor Nelson Rockefeller, the last of the major liberal Republicans who supported activist government and civil rights.

Until his death, Robinson continued speaking out. He was a constant presence on picket lines and at rallies on behalf of civil rights. He was one of the best fundraisers for the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, but he resigned from the organization in 1967, criticizing it for its failure to involve “younger, more progressive voices.” He pushed Major League Baseball to hire blacks as managers and executives and even refused an invitation to participate in an Old Timers game because he did not yet see “genuine interest in breaking the barriers that deny access to managerial and front office positions.”

During 1997 much of the fiftieth anniversary celebration of Robinson’s achievement—most of the news articles, movies, and museum exhibits—framed the integration of baseball as an individual’s triumph over adversity, as the story of a lone trailblazer who broke baseball’s color line on his athletic merits, with a helping hand from Dodger owner Branch Rickey.

But the true story of baseball’s integration is not primarily the triumph of either individualism or enlightened capitalism. Rather, it is a political victory brought about by social protest, part of the larger civil rights struggle. As historian Jules Tygiel explains in Baseball’s Great Experiment, beginning in the 1940s, the Negro press, civil rights groups, the Communist Party, progressive whites, and radical politicians waged a sustained campaign to integrate baseball. That push involved demonstrations, boycotts, political maneuvering, and other forms of pressure that would gain greater currency the following decade. Reporters for African American papers and for the Communist paper the Daily Worker kept the issue before the public. This protest movement set the stage for Rickey’s experiment and for Robinson’s entrance into the major leagues. The dismantling of baseball’s color line was a triumph of both a man and movement.

By hiring Robinson, the Dodgers earned the loyalty of millions of black Americans across the country. But they also gained the allegiance of many white Americans—most fiercely, American Jews, especially those in the immigrant and second-generation neighborhoods of America’s big cities—who believed that integrating the country’s national pastime was a critical stepping-stone to tearing down many other obstacles to equal treatment. In fact, however, the integration of baseball proceeded very slowly after Robinson’s entry into the big leagues, paralleling the slow progress of school integration in the larger society after the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education ruling.

Robinson recognized the paradoxes of racial progress in America. “I cannot possibly believe,” he wrote in his 1972 autobiography, I Never Had It Made, “that I have it made while so many black brothers and sisters are hungry, inadequately housed, insufficiently clothed, denied their dignity as they live in slums or barely exist on welfare.”

Robinson’s crusade helped move the country closer to its ideals. His legacy is also to remind us of the unfinished agenda of the civil rights revolution.