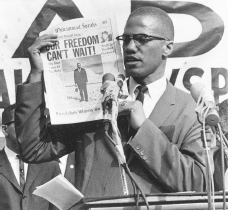

CREDIT: Associated Press

FOR MUCH of his life, FBI agent strailed Malcolm X’s every move, tapped his phone, and infiltrated meetings where he was speaking. The political and media establishment considered him a dangerous demagogue and hatemonger whose antiwhite rants could only exacerbate the nation’s racial tensions. But even FBI informants could not help but be impressed with the Nation of Islam preacher. In a 1958 memo one of them described Malcolm X as “an excellent speaker, forceful and convincing. He is an expert organizer and an untiring worker” whose hatred for whites “is not likely to erupt in violence as he is much too clever and intelligent for that.”

Malcolm X’s influence spread much farther than his religious followers. In the early 1960s he expressed the anger of many poor urban African Americans who felt trapped in ghettos and were the victims of humiliating police brutality, underfunded schools, and job discrimination. Before Malcolm, the Nation of Islam was a relatively small religious cult. His electrifying rhetoric and charisma attracted mainstream media attention, which gave him a much larger audience. His assassination in 1965 at age thirty-nine—probably at the hands of Nation of Islam rivals who resented his celebrity—heightened his fame.

Soon after his death, Grove Press published The Autobiography of Malcolm X. The book, written by Alex Haley based on long interviews with Malcolm, depicts his evolution from street hustler to controversial public figure. It quickly became a best seller. Since then, it has sold millions of copies and has become one of the most powerful memoirs in history, a staple of American culture, taught in high schools and colleges. Although the book exaggerates some parts of Malcolm’s story—whether because of Malcolm’s telling or Haley’s literary license is unclear—it is, like many autobiographies, a story of redemption. Malcolm pulled himself out of the hell of pimping, stealing, and drug dealing, finding spiritual salvation and intellectual enlightenment by virtue of an extraordinary self-discipline. He was, as his biographer Manning Marable noted, constantly evolving and reinventing himself. Toward the end of his life, Malcolm was abandoning his black separatism, embracing a more mainstream version of Islam, and revising his political views.

He was born Malcolm Little, the seventh of ten children, in Omaha, Nebraska, in 1925. As a young child, he absorbed the passion of his father. Earl Little was an itinerant Baptist preacher and an organizer for Marcus Garvey’s Universal Negro Improvement Association, a black self-help organization. Malcolm’s mother, Louise, was from the West Indies, the daughter of a white man she never knew.

When Malcolm was three, the family moved to Lansing, Michigan. Three years later, his father died a violent death. His battered body was found on the streetcar tracks, and many in the city’s black community believed he had been murdered by white supremacists. After her husband died, Louise found it impossible to put food on the table and went on public welfare. Malcolm recalled often being “dizzy” with hunger. His mother suffered a mental breakdown and in 1939 was institutionalized for the rest of her life.

Malcolm, already a troubled youth, was uprooted, being sent first to foster care and then to a detention home. At a mostly white junior high school, he was a bright student, but he grew disillusioned when his English teacher told him it was unrealistic for him to consider being a lawyer because of his race, suggesting that he take up carpentry instead. In the summer of 1940, when he was fifteen, he moved to Boston to live with his sister Ella. There he underwent the first of many transformations. He changed himself from a small-town restless teen to a streetwise hustler who furnished marijuana and bootleg liquor to white men whose shoes he shined.

He moved to Harlem and took on the persona of Detroit Red, selling drugs and running numbers up and down the East Coast. He also became a gun-toting drug addict and robber. Arrested with stolen property, in 1946 he received a ten-year prison term—and it was in prison, he wrote, that “I found Allah and the religion of Islam, and it completely transformed my life.”

He began his time in jail bitter and angry—so much so that his fellow prisoners nicknamed him “Satan.” His brother Philbert wrote him in prison and introduced him to the Nation of Islam. He quenched his thirst for knowledge in the prison library, copying words from a dictionary to expand his vocabulary and reading prodigiously, tackling Plato, Aristotle, Spinoza, Kant, Nietzsche, and Schopenhauer. He joined the prison debate club and became an effective public speaker, a skill that would serve him well. At the urging of another sister, Hilda, he wrote to the Nation of Islam’s leader, Elijah Muhammad. Muhammad responded, introducing Malcolm to the idea that “the white devil” was the true criminal in society.

After his release from prison in 1952, Malcolm went to Detroit to live with his brother and welcomed the chance to be part of a well-ordered, religious family that practiced Muslim traditions. His trip to Chicago to hear Elijah Muhammad speak was an electrifying experience, especially when Muhammad singled Malcolm out, asked him to stand, and told the audience about his prison conversion. After the meeting, Muhammad invited the Little family to dine in his eighteen-room home. Muhammad took a special liking to Malcolm and nurtured his leadership in the Nation of Islam.

In 1953 Malcolm Little took the name “Malcolm X” as a way of repudiating the “slave” name he had inherited as an African American. He began proselytizing door-to-door in poor Detroit neighborhoods, focusing especially on the most down-and-out. A gifted orator, he rose quickly through the ranks of the Nation of Islam, first as assistant minister of his Detroit mosque, then as a minister in Boston and Philadelphia, and finally as minister of Harlem Mosque No. 7, a congregation second in importance only to the Nation of Islam’s Chicago headquarters. In those cities, and as a speaker elsewhere, he drew in new recruits with his compelling presence. He was the Nation of Islam’s most gifted salesman.

During the late 1950s he was seen as the public voice of the Nation of Islam and was frequently interviewed in the media. He rejected the pacifism and integration advocated by Martin Luther King Jr. and the mainstream civil rights organizations. He argued instead for black nationalism, “which means that . . . the so-called Negro controls the politics and the politicians of his own community. Our people need to be re-educated into the importance of controlling the economy of the community in which we live, which means that we won’t have to constantly be involved in picketing and boycotting other people in other communities in order to get jobs.”

He espoused the primacy of racial dignity. In a 1964 radio interview, he encouraged “the black man to elevate his own society instead of trying to force himself into the unwanted presence of the white society.”

Malcolm’s indictment of white racism struck a chord with black Americans, especially those living in the urban ghettos. His fiery words—such as calling whites “blue-eyed devils”—struck fear into many white Americans, who imagined that Malcolm X was fomenting an armed rebellion by ghetto residents. He was portrayed in the media as an apostle of violence. Malcolm’s words were tough talk, but as the FBI informant recognized, they were more a matter of arming blacks psychologically to overthrow the negative self-images imposed by white racism. Malcolm was preaching black pride, much as Garvey had done a generation earlier and much as the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee and the Black Panthers did in the mid- and late-1960s when they proclaimed, “Black is beautiful.”

Although Malcolm said that the choice was between “the ballot or the bullet,” he clearly preferred the ballot. In April 1964, speaking in Cleveland at an event sponsored by the pacifist Congress of Racial Equality, Malcolm X said that President Lyndon B. Johnson and the Democrats in Congress should pass the Civil Rights Act if they wanted to avoid a black uprising. He observed:

All of us have suffered here, in this country, political oppression at the hands of the white man, economic exploitation at the hands of the white man, and social degradation at the hands of the white man. Now in speaking like this, it doesn’t mean that we’re anti-white, but it does mean we’re anti-exploitation, we’re anti-degradation, we’re anti-oppression. And if the white man doesn’t want us to be anti-him, let him stop oppressing and exploiting and degrading us. Whether we are Christians or Muslims or nationalists or agnostics or atheists, we must first learn to forget our differences.

The Nation of Islam was an inward-looking cult. Its members were told to avoid politics and not to vote. In contrast, Malcolm recognized that the civil rights movement had energized black Americans to demand full citizenship and an end to Jim Crow in the South and discrimination in the North. Although Malcolm regularly taunted civil rights leaders as “lackeys” and “Uncle Toms,” he also admired Martin Luther King Jr., A. Philip Randolph, Bayard Rustin, and others for their courage and movement-building skills. He even occasionally sought common ground with them. In 1962, for example, Malcolm joined with Los Angeles civil rights leaders to protest the killing of Ronald Stokes—an unarmed Muslim who had been a friend of his—in a parking lot. Elijah Muhammad objected to his consorting with the civil rights groups and his protesting against political authorities. It is no accident that Malcolm’s most important protégé and convert—boxer Cassius Clay, renamed Muhammad Ali—spoke out against the Vietnam War, a stance not approved by Elijah Muhammad.

By 1963 Malcolm had discovered that his spiritual leader was hardly an ascetic, as he demanded of followers, but, rather, had fathered several children through extramarital affairs. He confronted Muhammad about his activities, which further alienated him from his one-time mentor. Malcolm was also beginning to doubt the “white devil” theory, in part because of his encounters with light-skinned Arab Muslims during an international tour in 1959.

After President Kennedy was assassinated in November 1963, Malcolm defied Elijah Muhammad’s instructions and spoke out publicly, saying that the murder in Dallas represented “the chickens coming home to roost.” Angry that Malcolm’s inflammatory words might put the Nation of Islam at risk, Elijah Muhammad prohibited him from speaking for ninety days.

Politically, intellectually, and spiritually, Malcolm had outgrown the Nation of Islam. In March 1964 he broke with the group, knowing that doing so might mean he would be targeted for assassination.

Soon after founding a new group, the Muslim Mosque in New York, Malcolm went on a transformative two-month tour of Africa and the Middle East, including a hajj (pilgrimage) to Mecca. This journey further challenged his views, opening his mind to the potential for good in all people, regardless of race. He disavowed black separatism. He became a Sunni Muslim and changed his name again, to El-Hajj Malik El-Shabazz. His faith in black economic self-help and entrepreneurial capitalism shifted to socialism. As he wrote in a letter from Mecca to his assistants in Harlem:

You may be shocked by these words coming from me. But on this pilgrimage, what I have seen, and experienced, has forced me to re-arrange much of my thought-patterns previously held, and to toss aside some of my previous conclusions. . . . In the words and in the actions and in the deeds of the “white” Muslims, I felt the same sincerity that I felt among the black African Muslims of Nigeria, Sudan, and Ghana. . . . I could see from this, that perhaps if white Americans could accept the Oneness of God, then perhaps, too, they could accept in reality the Oneness of Man—and cease to measure, and hinder, and harm others in terms of their “differences” in color.

Until his death, he toured internationally, especially in Africa. He saw parallels between the anticolonial struggles in Africa and the struggles of African Americans. In June 1964 he formed the Organization of Afro-American Unity, and in July he attended the African Summit Conference in Cairo, appealing to the delegates of thirty-four nations to bring the cause of America’s black people before the United Nations.

Malcolm X was assassinated in 1965 as he was giving a speech at the Audubon Ballroom in New York. Three members of the Nation of Islam were found guilty of the murder, although controversy continues over who was ultimately responsible.