CREDIT: Associated Press

DURING THE 1970s, Ralph Nader was a household name, frequently interviewed and profiled in the media, regularly appearing in the Gallup Poll’s annual list of most-admired men in America. Beginning in 1965 with his exposé of the auto industry, Unsafe at Any Speed, and for three decades after that, Nader inspired, educated, and mobilized millions of Americans to fight for a better environment, safer consumer products, safer workplaces, and a more accountable government. Americans viewed Nader as a selfless David fighting the greedy Goliath of corporate America.

Although sometimes seen as a Lone Ranger, Nader worked closely with the consumer, environmental, community organizing, and labor movements to push for progressive reforms. He built a huge network of nonprofit organizations designed to investigate and advocate for reform, training thousands of Americans to be more effective organizers, researchers, and public interest lobbyists. Many people who got their start with one of Nader’s groups became influential activists, government officials, and journalists.

Thanks to Nader, our cars, airplanes, and workplaces are safer, our air and water is cleaner, and our food is healthier. We also have Nader to thank for seat belts and air bags. Over the years, millions of defective, unsafe cars have been recalled because of Nader’s work.

Nader played a key role in campaigns for such important milestones as the Clean Air Act (1970), the Safe Drinking Water Act (1974), and the Superfund Law (1980), which requires the cleanup of toxic-waste sites. He helped mobilize the public to get Congress to pass the Environmental Protection Act (1970), the Consumer Product Safety Act (1972), and the Occupational Safety and Health Act (1970) and to strengthen the Freedom of Information Act (1974). It is impossible to calculate the number of deaths and injuries prevented as a result of these landmark laws.

Nader was born in Winsted, Connecticut, to Lebanese restaurateur immigrants who instilled in him a strong belief in the importance of being an active citizen. He enjoyed reading copies of the Congressional Record (the speeches of members of Congress) that his high school principal gave him.

While studying at Princeton University, Nader tried but failed to stop the spraying of campus trees with the pesticide DDT, which he considered dangerous and harmful to the environment. (This was almost a decade before the publication of Rachel Carson’s Silent Spring.) He graduated magna cum laude from Princeton in 1955, majoring in government and economics. He attended Harvard Law School, where he was an editor of the Harvard Law Review, and upon graduation in 1958 he set up a small legal practice in Hartford, Connecticut.

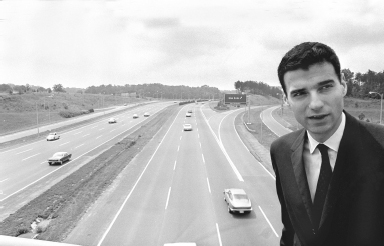

While still at Harvard, Nader investigated automobile injury cases and came to believe that design flaws, rather than driver error, were responsible for most car accidents. He testified on the subject before state legislative committees and wrote articles for magazines, including a landmark 1963 article in The Nation. Nader’s consequent book, Unsafe at Any Speed: The Designed-In Dangers of the American Automobile (1965) focused on the General Motors Corvair but indicted the whole auto industry for its indifference to safety. Nader testified before the Senate Government Operations Subcommittee’s hearings on auto safety. He soon became a target of auto manufacturers, who were hit with lawsuits by victims of auto accidents.

In March 1966 General Motors president James Roche admitted, in response to charges by Nader, that his company—then the most powerful corporation in the world—had hired detectives to harass Nader and to investigate his private life in order to discredit his views on car safety. The controversy generated media attention, made Nader a public figure, and turned Nader’s book into a best seller. This put the issue of auto safety on the public agenda, leading to the passage in 1966 of the National Traffic and Motor Vehicle Safety Act, one of the first auto safety laws.

Nader’s effort to fund a network of nonprofit organizations dedicated to investigating corporate abuse got a big boost after he sued General Motors for $26 million for invasion of privacy and was awarded $425,000, which he used to hire a small army of young law students and college graduates, dubbed “Nader’s Raiders.”

During the late 1960s and 1970s, Nader’s low-paid but dedicated researchers published a remarkable series of reports on irresponsible corporate practices and lax government regulation. Their early studies focused on mine safety, the dangers of oil and gas pipes, water pollution, nursing home fraud, pesticides in agriculture, and—like Upton Sinclair’s work several generations earlier—food safety. The resulting publicity led to the 1967 Wholesome Meat Act.

In 1968 Nader’s task force of law students investigated the Federal Trade Commission (FTC), which had been created to protect consumers from shoddy products, fraudulent business practices, and deceptive advertising. They found that the agency was virtually held hostage by the industries it was supposed to monitor and regulate. The report triggered a congressional investigation and a major overhaul of the FTC.

In 1969 he founded the Center for the Study of Responsive Law, which examined incompetence and corruption at the Interstate Commerce Commission, the hazards of air pollution, and the Food and Drug Administration’s lax oversight of the food industry. Nader recruited several hundred college students to profile every member of Congress and six key congressional committees. The resulting best-selling book, Who Runs Congress?, educated the public about Congress’s inner workings. This project turned into Congress Watch, which for years advocated for sunshine laws that opened up congressional committees to public exposure and led to new rules that have weakened the power of entrenched committee chairpersons.

Nader has been a staunch critic of government subsidies for business, including the nuclear power industry, the aerospace industry, agribusiness, the synthetic fuel industry, and dozens of others. “Ours is a system of corporate socialism,” Nader explained, “where companies capitalize their profits and socialize their losses. In effect, they tax you for their accidents, bungling, boondoggles and mismanagement, just like a government. We should be able to dis-elect them.”

Time magazine called Nader the country’s “toughest customer.” The New York Times said, “What sets Nader apart is that he has moved beyond social criticism to effective political action.” As Nader became increasingly well-known and his reform efforts more successful, business groups tried to tarnish his reputation, in part by challenging his findings (which they were rarely able to do successfully). Nader’s own frugal lifestyle contributed to his image as a selfless and incorruptible crusader, a Pied Piper of citizen activism.

Nader’s reports scrutinized the failures of federal agencies to protect consumers, workers and the environment, and they investigated the ties between big business and politicians. They named names, meticulously documented abuses, and proposed practical solutions. In the early 1970s Nader founded the Capitol Hill News Service, which pioneered investigative reporting about Congress. Nader’s Freedom of Information Clearinghouse trained journalists in how to obtain government documents. In this way, Nader was following the tradition of such early muckrakers as Lincoln Steffens and Upton Sinclair and such postwar gadflies as I. F. Stone.

Nader did more than unmask specific scandals. His organizations became ongoing watchdogs of big business and government, a role that the mainstream media, with greater resources, only occasionally played. He also started a network of campus-based organizations called public interest research groups (PIRGS) that have trained thousands of college students in the skills of citizen activism, published hundreds of reports, drawn attention to environmental and energy problems, and lobbied for hundreds of laws in state legislatures. Nader also led efforts to reform university governance, educational testing, legal services, and professional sports.

In 1980 Nader resigned as director of the consumer advocacy organization Public Citizen but continued his activism. Freed from the day-to-day oversight of his many nonprofit organizations, Nader took on wider issues of corporate power, including campaign finance, health insurance, trade, telecommunications, and banking. During the Reagan era and beyond, his challenges to big business became more radical as he indicted the whole corporate system rather than just specific industries. Increasingly, he attacked both major political parties as pawns of corporate America, dependent on contributions from big business and the very rich.

Had Nader retired in the early 1990s, his reputation and legacy as one of American history’s most effective progressive leaders would have been secure. But he decided to run for president in 1996 and 2000 on the Green Party ticket and in 2004 as an independent.

Some Nader supporters encouraged him to run in the Democratic Party primaries, where he might have gotten considerable TV and radio airtime in the debates. They argued that although he would not have won the nomination, he could have helped strengthen the progressive wing within the party, as Jesse Jackson did in 1988 and 1992.

But because Nader saw both the Democratic and Republican Parties as essentially the same—as tools of corporate America—he chose to run as a third-party candidate. He claimed that his campaigns would help build a permanent progressive third party that could contest for power. But that influential third party never materialized, mostly because America’s winner-take-all rules make it virtually impossible for third parties to gain traction, but also because Nader never devoted himself to the hard work of party building.

During his 2000 campaign, Nader argued that there was virtually no difference between Democratic candidate Al Gore and Republican candidate George W. Bush. He won nearly 3 million votes nationwide, close to 3 percent of the votes cast. After the scandalous miscounting of votes in Florida, Bush “officially” beat Gore by 537 votes (out of more than 5.8 million cast), making it the closest presidential election in the state’s history. This gave Bush Florida’s twenty-five Electoral College votes and, with the help of the US Supreme Court in Bush v. Gore, the presidency.

Nader won 97,488 votes in Florida. Polls showed that some of Nader’s supporters would have stayed home if he had not been in the race, but most would have voted for Gore. A week before election day in November, when polls showed Gore and Bush neck and neck, many progressives urged Nader to encourage his supporters to vote for Gore in order to avoid a Bush victory. Many believe that had he done that, Gore would have beaten Bush.

Nader was unable to translate his reputation as an incorruptible reformer into support for his electoral campaigns, making him an increasingly marginalized figure in American politics.