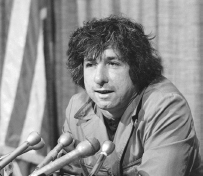

CREDIT: Associated Press/George Brich

INSPIRED BY Jack Kerouac’s On the Road, Tom Hayden, the twenty-year-old editor of the Michigan Daily (the University of Michigan’s student newspaper), took a cross-country hitchhiking trip during the summer of 1960.

During his trip, Hayden visited the San Francisco area, where he met activists who were organizing pickets in front of Woolworth’s and Kresge five-and-dime stores to support the southern sit-ins. Some activists took Hayden to Delano, California, a rural agricultural area, where he encountered the near-slavery under which Mexican farmworkers toiled. He also interviewed Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., who was walking a picket line outside the 1960 Democratic convention in Los Angeles to demand that the party endorse a strong civil rights platform.

“There I was,” Hayden recalled years later, “with pencil in hand, trying to conduct an objective interview with Martin Luther King, whose whole implicit message was: ‘Stop writing, start acting.’ That was a compelling moment.” King gently told Hayden, “Ultimately, you have to take a stand with your life.” When Hayden returned to Ann Arbor that fall, he committed himself to the life of an activist.

No single figure embodies the spirit of that generation more than Tom Hayden. He played a part in almost every aspect of the decade’s major battles for justice. He remained an activist during the 1970s, 1980s, and 1990s and into the 21st century, working to build a progressive movement based on values of social justice and grassroots democracy.

Named for St. Thomas Aquinas, Hayden went to Catholic schools in Royal Oak, Michigan, an all-white middle-class Detroit suburb. By the time he reached high school, Hayden was already an iconoclast. The editor of his school paper, Hayden was banned from attending his own graduation and kicked out of the National Honor Society for writing an incendiary editorial.

In the spring of 1960, thirty-two-year-old Michael Harrington, by then a veteran socialist activist, met Hayden in Ann Arbor at a student conference about civil rights. Harrington and Hayden had much in common—they were both midwestern middle-class Irish Catholics, with literary and journalistic bents—but Hayden resisted Harrington’s efforts to recruit him to the Socialist Party’s youth group, thinking that joining a group labeled “socialist” would immediately marginalize him, particularly at a time when the Red Scare was still a strong force in American politics. Hayden helped organize VOICE, a left-liberal campus political party that called for a greater “student voice in the decisions affecting our lives.” Ann Arbor activists Al Haber and Bob Ross recruited Hayden to join Students for a Democratic Society (SDS), which began in 1960 as a vehicle to enlist white students on northern campuses to support the southern civil rights movement.

Along with the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), SDS became the decade’s key catalyst for recruiting and radicalizing some of the babyboom generation’s most effective activists.

In late 1960 Hayden agreed to be SDS’s first field secretary—or organizer. He worked on voter registration campaigns, joined protest marches in Mississippi, and participated in the Freedom Rides. In the South, he was inspired by the courage of SNCC volunteers (one of whom, Sandra Cason, he married), especially Bob Moses. He filed stories about these events for the Michigan Daily, Progressive magazine, and even Mademoiselle.

Hayden began writing the SDS manifesto—what would become the Port Huron Statement—while sitting in a jail in Albany, Georgia. (He had been arrested for trying to integrate the waiting room in the local train station.) His draft was circulated to SDS supporters around the country. A group of members convened at a union retreat center in Port Huron, Michigan, to debate the document and plot the organization’s—and their generation’s—future. The document reflected the early SDSers’ hope for a new beginning in American political life, inspired by the nonviolent direct action of the southern civil rights movement and the growing protests against the nuclear arms race.

The Port Huron Statement begins: “We are people of this generation, bred in at least modest comfort, housed now in universities, looking uncomfortably to the world we inherit.”

SDS believed that young people could play a role in changing America. It asserted a vision of society rooted in the concept of participatory democracy. Under Hayden’s leadership, SDS played a significant part in four major issues:

•Lessening restrictions to free speech and political activism on college campuses

•Supporting the southern civil rights movement

•Mobilizing student opposition to the war in Vietnam

•Setting up community organizing projects to help mobilize the poor.

Hayden moved to New Jersey in 1964 to build the Newark Community Union. For over three years, Hayden and his colleagues knocked on doors in Newark’s black ghetto, recruiting jobless and low-wage residents into the community group, which aimed to help them gain a voice over such problems as slum housing, police brutality, inadequate schools, and other issues. But progress was slow, and Hayden, like the poor residents trapped in Newark’s ghetto, began to lose patience as corrupt local white politicians resisted change and as funding for Lyndon B. Johnson’s War on Poverty gave way to funding for the Vietnam War. In August 1967 Newark’s ghetto exploded in riots, one of dozens of urban uprisings (including one in Detroit) during that “long hot summer.” Hayden wrote a long analysis of the roots of the riot in his book Rebellion in Newark.

While living in Newark, Hayden devoted careful study to the history and culture of Vietnam and to US foreign policy in Southeast Asia. In 1965 he joined pacifist historian Staughton Lynd and Communist Party official Herbert Aptheker on a fact-finding trip to North Vietnam, a journey that violated US State Department rules and was attacked in the media. He and Lynd wrote a book, The Other Side, about their journey. In 1967 he returned to North Vietnam with other antiwar activists to investigate the human impact of US bombing. While they were there, the North Vietnamese government asked them to bring home several American prisoners of war. Because the United States did not recognize the Hanoi government, the Vietnamese wanted to release them to Americans involved in the peace movement. The release was viewed as both an act of humanitarianism and a propaganda gesture.

The optimism of the 1962 Port Huron Statement reflected the views of the early leaders of SDS, who were, like Hayden, born in the late 1930s and early 1940s. By the middle and late 1960s, many of these early SDSers, as well as many of the somewhat younger baby-boom generation of radicals, had lost faith in liberalism. The Kennedy administration’s reluctance to reign in the vigilantes and law enforcement officials who perpetrated or condoned violence against civil rights activists, the conflict over seating the integrated Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party at the 1964 Democratic convention, the bloody escalation of the Vietnam War, America’s opposition to anticolonial movements in the Third World, and the urban riots of the decade led some activists to embrace a strident attitude. They considered moderates and liberals as obstacles to progress, viewing them with almost the same disdain they held for segregationists, conservatives, and the military-industrial complex.

By 1967, America’s growing military presence in Vietnam began to change public opinion and to increase opposition to the war. Many liberals and religious groups protested, but under LBJ the war and the death toll continued. To many frustrated and impatient antiwar activists, the United States felt like a war machine, not a democracy.

Hayden’s antiwar activities embodied a distinctive combination of political pragmatism and moral outrage. He worked with SDS and other groups to organize protest rallies. He wrote for a variety of publications, attacking US policy and describing Vietnamese history and culture. In April 1968 he helped SDSers at Columbia University who occupied several buildings and shut down the university to protest both its no-longer-secret affiliation with research projects funded by the Defense Department and its plans to expand its campus into nearby Harlem.

By the late 1960s, many radicals had begun to view the war as an inevitable outcome of America’s empire building, lust for profits, and racism toward the world’s populations of color. Frustrated, some called for more-militant tactics, including burning draft cards (a federal crime). Hayden often shared this perspective, but he not only opposed violence and bombings, he also still had faith in the potential of electoral politics, particularly the promise of Robert Kennedy’s 1968 antiwar and antipoverty campaign.

Kennedy’s assassination that June was traumatic for the country and for Hayden. At Kennedy’s funeral in St. Patrick’s Cathedral in New York City, he cried over the tragic loss of the one politician who had the potential to unite the antiwar and antipoverty movements. That summer, Hayden joined other activists in planning protests at the Democratic convention, scheduled for late August in Chicago.

For eight days during the convention, protesters and the Chicago Police Department battled for control of the streets, while the Democrats nominated Vice President Hubert H. Humphrey as their standard-bearer. An official investigation would later describe the violence as “police riots.” Despite this finding, the administration of newly elected Richard Nixon indicted Hayden and seven others for “conspiracy” to riot. The trial made headlines for months, as both sides used theatrics to turn the court proceedings into a political battleground. Hayden privately opposed some of the antics of his codefendants, particularly Jerry Rubin and Abbie Hoffman. Hayden nevertheless gained a reputation as a radical who condoned street violence. Hayden and five of the others were convicted in 1969 but were acquitted on appeal in 1973.

In the early 1970s Hayden began to rethink the antiwar movement’s strategy. In 1972 he and other peace activists formed the Indochina Peace Campaign (IPC). They brought speakers, slide shows, and music to churches, campuses, and venues near military bases (to attract disillusioned soldiers) in order to educate the public about the war and to urge them to vote for antiwar candidates. During this period, Hayden met and married actress Jane Fonda, who had become a high-profile opponent of the war. IPC succeeded in pushing Congress to reduce war appropriations.

In 1971 Hayden moved to Santa Monica, California. He decided to challenge Senator John Tunney, a moderate Democrat who had supported the Vietnam War and who was running for reelection, in the 1976 Democratic primary. With Fonda’s seed money, he knitted together a feisty statewide campaign, but he found himself attacked by some leftists for working within the system. The media also assailed Hayden for what they considered his radical views. Although no major daily newspaper endorsed him, Hayden shocked political pundits by garnering about 40 percent of the vote.

After the election, Hayden and others founded the Campaign for Economic Democracy (CED). In its decade-long existence, CED won local and statewide victories on rent control and solar energy, helped shut down a nuclear power plant through a referendum (the first successful antinuclear referendum), led a successful campaign to require labels on cancer-causing products, and won a statewide ballot campaign to triple tobacco taxes to fund public health and antitobacco initiatives. It also helped elect more than a dozen progressive candidates to office.

One of those candidates was Hayden, who was elected to the California State Assembly in 1982 and to the state Senate ten years later. Overall, he served eighteen years in the state legislature. The Sacramento Bee described Hayden as “the conscience of the Senate.” While serving in the legislature, he worked closely with progressive groups to sponsor and enact legislation on a variety of environmental, educational, public safety, and human rights issues. Concerned about the upsurge of gang violence between African Americans and Latino immigrants in Los Angeles, he played a key role in negotiating a gang war truce and wrote a book about the experience, Street Wars, in 2005.

Ironically, the state legislature was Hayden’s longest-lasting political home. Although he built a number of organizations over the years, none lasted long enough to sustain his career as an activist. Since leaving public office, he has earned his living by writing, speaking, organizing, and teaching. He has written eyewitness accounts of the global justice movements around the world, including moving firsthand accounts of the 1999 protests against the World Trade Organization (the “Battle in Seattle”). He played an important role in organizing opposition to the war in Iraq and penned a book on the subject, Ending the War in Iraq.

In 2008 Hayden helped launch Progressives for Obama, investing in the young Illinois senator some of the same hopes he had had for Robert Kennedy. After Barack Obama took office, Hayden supported his progressive initiatives but criticized what he considered the new president’s weak policies to bolster the economy and his reluctance to quickly withdraw troops from Iraq and Afghanistan. Soon after the 2008 election, Hayden committed most of his energy to organizing opposition to the war in Afghanistan. Once again, Hayden understood the necessity of linking outsiders and insiders to bring about needed change. “No sooner had a social movement elected [Obama] than it was time for a new social movement to bring about a new New Deal,” Hayden wrote. “Lest his domestic initiatives sink in the quagmires of Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, a new peace movement must rise as well.”