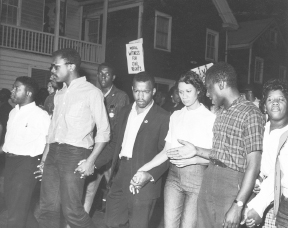

John Lewis, third from left, links hands with others during a march in protest of a scheduled speech by the pro-segregationist Alabama governor, George Wallace, Cambridge, Maryland, May 1964.

CREDIT: Photo by Francis Miller/Time & Life Pictures/Getty Images © Time Life Pictures

ONLY A handful of the 250,000 people at the March on Washington in August 1963 knew anything about the drama taking place behind the Lincoln Memorial. Under A. Philip Randolph’s leadership, the march had brought together the major civil rights organizations. A representative of each group would address the huge crowd. Bayard Rustin, who was in charge of the event’s logistics, required all speakers, even Martin Luther King Jr., to hand in the texts of their speeches the night before. The speech submitted by the twenty-three-year-old chairman of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), John Lewis, criticized President John F. Kennedy for moving too slowly on civil rights legislation. Rustin, Randolph, and others considered Lewis’s text inflammatory, threatening the unity they had so carefully built for the event. It included these lines:

The revolution is a serious one. Mr. Kennedy is trying to take the revolution out of the street and put in the courts. Listen, Mr. Kennedy. Listen, Mr. Congressman. Listen, fellow citizens. The black masses are on the march for jobs and freedom, and we must say to the politicians that there won’t be a “cooling-off” period. We won’t stop now. The time will come when we will not confine our marching to Washington. We will march through the South, through the Heart of Dixie, the way Sherman did. We shall pursue our own “scorched earth” policy and burn Jim Crow to the ground—nonviolently.

The evening before the march, Patrick O’Boyle—the archbishop of Washington, who was scheduled to give the rally’s invocation—saw Lewis’s speech. A staunch Kennedy supporter, he alerted the White House and told Rustin that he would pull out of the event if Lewis was allowed to give those remarks.

The next day, as the marchers assembled in front of the Lincoln Memorial, the controversy over Lewis’s speech continued behind the stage. An intense argument, with raised voices and fingers shaking in each other’s faces, broke out between Lewis and Roy Wilkins, the director of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. Rustin persuaded O’Boyle to start the program with his invocation while an ad hoc committee battled with Lewis over the language of his speech. Finally Randolph, the civil rights movement’s beloved elder statesman, appealed to Lewis. “I’ve waited all my life for this opportunity,” he said. “Please don’t ruin it, John. We’ve come this far together. Let us stay together.”

Lewis toned down the speech. His closing paragraphs no longer had the incendiary reference to William Tecumseh Sherman’s march, but the address remained a powerful indictment of politicians’ failure to deal boldly with discrimination. Lewis’s skepticism toward the Kennedy administration was understandable. Lewis had risked his life as a Freedom Rider, but the White House had been reluctant to use federal troops to protect the protesters. Kennedy had referred to the SNCC activists as “sons of bitches” who “had an investment in violence.” His brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, told a reporter that the violence surrounding the Freedom Rides provided “good propaganda for America’s enemies.”

Lewis was lucky to survive the Freedom Rides without permanent injury. Indeed, that Lewis was speaking at the March on Washington at all reflected a remarkable personal transformation and act of self-discipline. Born into a large family of sharecroppers in Alabama, Lewis was shy and suffered from a speech impediment. At fifteen he heard King’s speeches and sermons on the family radio during the Montgomery, Alabama, bus boycott and decided to become a minister. He practiced preaching to chickens in his parents’ barnyard and then preached at local Baptist churches.

At seventeen, after becoming the first member of his family to graduate from high school, he attended the American Baptist Theological Seminary in Nashville, Tennessee, which allowed students to work in lieu of tuition. He worked as a janitor and simultaneously attended the all-black Fisk University, graduating with degrees from both the seminary and the university.

Rev. Kelly Miller Smith, a local black minister and activist, introduced Lewis to James Lawson, a divinity student at nearby Vanderbilt University, who was conducting workshops on nonviolent social action through the Fellowship of Reconciliation. Lawson prepared his students intellectually, psychologically, and spiritually, assigning the works of Mohandas Gandhi, Henry David Thoreau, and theologian Reinhold Niebuhr. The students debated whether they could learn to forgive, even love, white segregationists who might beat them. They wondered if they had the self-discipline not to strike back, especially if they were called “nigger” or other epithets while being hit.

Lewis spent a weekend at a Highlander Folk School retreat, where he met Myles Horton, Septima Clark, and other activists who helped him visualize what could happen if thousands of poor working people—folks like Lewis’s parents—were galvanized into direct action. “I left Highlander on fire,” Lewis recalled. The fire got even hotter in the summer of 1959, when Lewis attended a workshop at Spelman College in Atlanta, Georgia, and heard veteran organizers Bayard Rustin, Ella Baker, Glenn Smiley, and Lawson discuss what it would take to dismantle Jim Crow.

When Lewis returned to college in the fall, the number of students attending Lawson’s workshops had grown and included some white students from Vanderbilt. As Lewis wrote in his memoir, Walking with the Wind, “We were itching to get started.” They planned to launch a full-scale nonviolent protest campaign targeting the major downtown department stores that refused to serve black people. But to their surprise, on February 1, 1960, four students from the Agricultural and Technical College in Greensboro, North Carolina, beat them to it, organizing a sit-in at the local Woolworth’s. The news generated excitement on Nashville’s campuses. Hundreds of students emulated their Greensboro counterparts and were threatened with arrest. Lewis wrote up a list of dos and don’ts to help out the students:

Do Not: Strike back nor curse if abused. Laugh out. Hold conversations with a floor walker. Leave your seat until your leader has given you permission to do so. Block entrances to stores outside nor the aisles inside.

Do: Show yourself friendly and courteous at all times. Sit straight: always face the counter. Report all serious incidents to your leader. Refer information seekers to your leader in a polite manner. Remember the teachings of Jesus Christ, Mahatma Gandhi and Martin Luther King.

Lewis was arrested at Woolworth’s for the first of many times in his life. So too were hundreds of other protestors at other stores. Day after day, Lewis and the other students sat silently at lunch counters where they were harassed, spit upon, beaten, and finally arrested and held in jail, but the students insisted that they continue. The protests continued, with Lewis playing a key leadership role, and eventually Nashville’s mayor and business leaders agreed to desegregate the downtown stores.

Lewis’s physical and spiritual courage would be tested many times over the next few years. Each time, he revealed a remarkable, calm discipline, galvanizing others to follow his lead. The success of the sit-in movement led Lewis and his counterparts across the South to start SNCC in April 1960.

In May 1961, the twenty-one-year-old Lewis participated in Freedom Rides organized by the Congress of Racial Equality to protest the segregation of interstate bus travel and terminals. Lewis was on the first Freedom Ride, which left Washington, DC, on March 4 destined for New Orleans, Louisiana. When they reached Rock Hill, South Carolina, and got off the bus, Lewis tried to enter a whites-only waiting room. Two white men attacked him, injuring his face and kicking him in the ribs.

Nevertheless, only two weeks later, Lewis was one of twenty-two Freedom Riders—eighteen blacks, four whites—on another Freedom Ride bus from Nashville to Montgomery, accompanied by a protective escort of state highway patrol cars. As they reached the Montgomery city limits, the state highway patrol cars turned away, but no Montgomery police appeared to replace them. When the bus arrived at the Greyhound terminal, several reporters approached Lewis to interview him. But they were quickly overwhelmed by a mob of angry whites carrying baseball bats, bricks, chains, wooden boards, tire irons, and pipes, screaming “git them niggers.” As Lewis wrote in his memoir: “I felt a thud against my head. I could feel my knees collapse and then nothing. Everything turned white for an instant, then black. I was unconscious on that asphalt. I learned later that someone had swung a wooden Coca-Cola crate against my skull. There was a lot I didn’t learn about until later.”

When he regained consciousness, he was bleeding badly from the back of his head and his coat, shirt, and tie were covered with blood. Jim Zwerg, a white Freedom Rider, was in much worse shape. Lewis asked a police officer to help him get an ambulance, but the cop simply said, “He’s free to go.”

Two days later, the battered Lewis was back on another Freedom Ride bus, heading to Jackson, Mississippi, but this time with National Guard escorts. When they arrived at the terminal, a police officer pointed them toward the “colored” bathroom, but Lewis and the others headed toward the “white” men’s room and were promptly arrested. Twenty-seven Freedom Riders were jailed. Lewis and others were later moved to the notorious Parchman Penitentiary state prison, which they had to endure for over three weeks.

Over the next few years, Lewis worked with SNCC to register voters, including in the Freedom Summer campaign in Mississippi. In 1965 he led 600 protesters on the first march from Selma, Alabama, to Montgomery. Police attacked the marchers, and Lewis was beaten so severely that his skull was fractured. Before he could be taken to the hospital, he appeared before the television cameras calling on President Lyndon B. Johnson to intervene in Alabama. The day, March 7, 1965, came to be known as “Bloody Sunday.”

The Freedom Rides forced the federal government to implement laws and court rulings desegregating interstate travel. The voter registration drives, as well as public outrage against the violence directed at nonviolent protesters, helped secure passage of the Voting Rights Act.

The slow pace of change and the unrelenting attacks by southern whites led some SNCC activists to question the nonviolent and integrationist tenets preached by King, Lawson, Lewis, and others. Friction grew between various camps within SNCC. Lewis lost his post as SNCC chair to the more militant Stokely Carmichael.

For the next seven years, Lewis directed the Voter Education Project (VEP), which registered and educated about 4 million black voters. President Jimmy Carter then appointed Lewis director of ACTION, the federal agency that oversaw domestic volunteer programs.

In 1981 Lewis was elected to the Atlanta City Council. Five years later, he was elected to Congress from an Atlanta district, and he has been reelected every two years since. After becoming an “insider,” Lewis continued to advocate for progressive causes regarding poverty, civil rights, and foreign affairs. In 2009 he was one of several members of Congress arrested outside the embassy of Sudan, where they had gathered to draw attention to the genocide in Darfur. He was an early opponent of the US invasion of Iraq. In 2002 he sponsored the Peace Tax Fund bill, a conscientious objection to military taxation introduced yearly since 1972. In 2011 President Barack Obama awarded Lewis the Presidential Medal of Freedom.

In 1989 Lewis returned to Montgomery to help dedicate a civil rights memorial. An elderly white man came up to him and said, “I remember you from the Freedom Rides.” Lewis took a moment to recall the man’s face. Then he recognized Floyd Mann, who had been Alabama’s safety commissioner. A committed segregationist, tough on law and order, Mann had been assured by Montgomery’s police chief that no violence would occur. Seeing the white mob attack the Freedom Riders as they got off the bus, Mann realized he had been double-crossed. He charged into the bus station, fired his gun into the air and yelled, “There’ll be no killing here today.” A white attacker raised his bat for a final blow. Mann put his gun to the man’s head. “One more swing,” he said, “and you’re dead.” When they met again, Lewis whispered to Floyd Mann, “You saved my life.” The two men hugged, and Lewis began to cry. As they parted, Mann said, “I’m right proud of your career.”