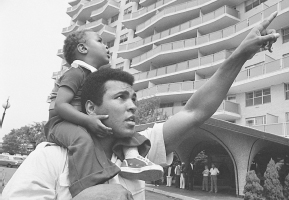

CREDIT: Associated Press/Bill Ingraham

AT THE opening ceremonies of the 1996 Olympic Games in Atlanta, Georgia, Muhammad Ali suddenly appeared on a platform in the stadium. Janet Evans, a five-time Olympic medalist in swimming, passed the heavy Olympic torch to Ali. Shaking from Parkinson’s disease and perhaps also from nervousness, he stood for a moment acknowledging the cheering crowd. Then he lit the cauldron that symbolized the official start of the Olympics. His role had not been announced in advance, so his appearance was a surprise to all but a handful of the spectators in the stadium and to the billions around the world watching on television. Already one of the most recognizable figures in the world, Ali had been selected to represent the United States, the host country.

This was a long way from the 1960s and 1970s, when, to many white Americans, Ali—the former Cassius Clay and one-time heavyweight champion of the world—was vilified as a menacing black man, a symbol of a “foreign” religion (Islam), and a fierce opponent of America’s war in Vietnam who defied his government by refusing to be drafted, risking prison and the withdrawal of his boxing title.

Ali is regarded as one of the greatest boxers in history, even though his career was interrupted for more than three years. At his peak, powerful figures in government, media, and sports inflicted great hardship on the boxer-turned-activist for following his religious and political convictions. Eventually, Ali transcended his role as a sports figure to become a man acclaimed around the world as a person of conscience.

He was born Cassius Clay in Louisville, Kentucky, part of the Jim Crow South. His father was a house painter and his mother was a domestic worker. When he was twelve, Clay’s bike was stolen. He told a police officer, Joe Martin, that he wanted to beat up the thief. Martin, who also trained young boxers at a local gym, started working with Clay and quickly recognized his raw talent. Clay won the 1956 Golden Gloves Championship for light heavyweight novices and three years later won the Golden Gloves Tournament and the Amateur Athletic Union’s light heavyweight national title. In 1960 the eighteen-year-old Clay won a spot on the US Olympic Boxing Team and returned from Rome a hero with the gold medal.

The next week, Clay went to a segregated Louisville restaurant with his medal swinging around his neck and was denied service. He threw the medal in the Ohio River.

He quickly turned professional and seemed unbeatable. He won his first nineteen bouts, most of them by knockouts. In 1964, in a match in which he was considered an underdog, he knocked out Sonny Liston to become the heavyweight champion of the world at age twenty-two.

Unlike most boxers, Clay was brash, articulate, and colorful outside the ring. He referred to himself as “The Greatest.” He wrote poems predicting which round he would knock out his opponents. As a fighter, Ali was incredibly fast, powerful, and graceful. He told reporters he could “float like a butterfly, sting like a bee.”

In his personal life, however, he was on a spiritual quest. In 1962 Malcolm X recruited him to the Nation of Islam, which was known to the public as the “black Muslims” and was almost universally condemned by the mainstream media, by white politicians, and by most civil rights leaders, who disagreed with the Nation of Islam’s belief in black separatism. Clay waited until the day after he beat Liston in 1964 to announce that he had joined the Nation of Islam and that he had changed his name to Muhammad Ali.

At that point, the public turned against Ali. Most reporters initially refused to call him by his new name and attacked his association with Malcolm X. Even Martin Luther King Jr. told the press, “When Cassius Clay joined the Black Muslims, he became a champion of racial segregation and that is what we are fighting against.” Many black Americans who disagreed with the Nation of Islam nevertheless admired Ali’s defiance. In 1965, when some Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC) volunteers in Alabama launched an independent political party, the Lowdes County Freedom Organization, using the symbol of a black panther, the slogan on their bumper stickers and T-shirts came straight from Ali: “We Are the Greatest.”

Ali’s announcement jeopardized many commercial endorsement opportunities. The media pressed Ali to explain his convictions. “I’m the heavyweight champion,” he said, “but right now there are some neighborhoods I can’t move into.”

Despite the controversy, he continued to dominate in the ring, besting all opponents who sought to topple him off his heavyweight throne.

Ali also found himself in another fight—a battle within the Nation of Islam between Malcolm X and Elijah Muhammad. When Muhammad suspended Malcolm X, Ali sided with Muhammad and broke off all relations with his mentor, with whom he had become close friends. When Malcolm X was assassinated in February 1965, Ali’s public comments were chilling: “Malcolm X was my friend and he was the friend of everybody as long as he was a member of Islam. Now I don’t want to talk about him.”

Despite this break, Ali had absorbed Malcolm X’s political views, which were more radical than those of the Nation of Islam. In 1966 Ali was drafted by the US Army. Had he agreed to join the military, he would not have had to fight in Vietnam but would instead have served as an entertainer for the troops. But Ali refused military service, asserting that his religious beliefs prohibited him from fighting in Vietnam. “I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong,” Ali explained. Another Ali explanation—“No Vietcong ever called me nigger,” which suggested that US involvement in Southeast Asia was a form of colonialism and racism—became one of the most famous one-line statements of the 20th century.

“When Ali refused to take that symbolic step forward everyone knew about it moments later,” explained Julian Bond, a SNCC leader and later head of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). “You could hear people talking about it on street corners. It was on everybody’s lips. People who had never thought about the war—Black and white—began to think it through because of Ali.”

The US government denied Ali’s claim for conscientious objector status on the grounds that his objections were political, not religious. Ali reported to the induction center but refused to respond when his name was called. He was arrested and found guilty of refusing to be inducted into the military. He was sentenced to five years in prison, and his passport was revoked. He remained free pending many appeals. Even though he was not in prison, he was banned from boxing after its governing body stripped him of his boxing title and suspended his boxing license.

Ali was not permitted to box for over three years at the height of his athletic ability, from age twenty-five to twenty-eight. During those years he was a frequent speaker on college campuses, speaking out against the ongoing Vietnam War.

By 1970 public opinion about Vietnam, and about Ali, was changing, and the boxing establishment allowed Ali to fight again. Ali beat Oscar Bonavena at Madison Square Garden. But on March 8, 1971, also at Madison Square Garden, Ali failed in his attempt to regain the heavyweight title from the undefeated Joe Frazier.

Three months later, the US Supreme Court voted 8–0 to reverse his draft evasion conviction. But the Court could not give him back the three years and millions of dollars he lost during his boxing exile.

Ali kept fighting. Between 1971 and 1973, he beat Ken Norton, George Chuvalo, Floyd Patterson, and Frazier in a 1974 rematch. In October of that year the underdog Ali defeated the younger, hard-hitting champion George Foreman with an eighth-round knockout and reclaimed the heavyweight crown, in a fight in Zaire that the media called the “Rumble in the Jungle.” The next year Ali defeated Frazier in the “Thrilla in Manila,” one of the greatest battles in boxing history. In both Africa and the Philippines, Ali was greeted as a hero by people in the streets.

In February 1978 an overconfident Ali lost his championship belt to Leon Spinks, the 1976 Olympic champion. Friends urged Ali to retire, but he wanted to keep fighting. That September Ali defeated Spinks, becoming boxing’s first three-time heavyweight champion. The next June he announced his retirement. He came out of retirement to fight again, revealing a dramatic decline in his skills. He retired for good in 1981 with an overall professional record of fifty-six wins and five losses.

By then, Ali was possibly the most recognized individual in the world, not only for his boxing achievements but also for his political views and courage. He left the Nation of Islam in 1975 (at the death of Elijah Muhammad), converting to Sunni Islam in 1982. He announced that he had Parkinson’s disease in 1984.

Since his retirement, he has devoted much of his time to world travel and humanitarian work, such as his efforts with Amnesty International. In 1990 Ali traveled to Baghdad to negotiate for the release of US hostages held by Saddam Hussein. After ten days of negotiations, which included Ali’s submitting to the indignity of a strip search prior to meeting with Saddam, he returned to the United States with the fifteen former captives.

In 1998 he was chosen to be a UN Messenger of Peace because of his work in developing countries. In 2005 he received the Presidential Medal of Freedom and in 2009 the President’s Award from the NAACP for his public service efforts.

Political activism has never been widespread among athletes. Most dissident athletes have been African Americans. Ali was venturing into territory untried by any except Jackie Robinson. (Boxer Joe Louis quietly challenged racism in the military during World War II, but he never did so publicly.) The civil rights and antiwar movements, however, inspired some athletes to speak out. Bill Russell led his teammates on boycotts of segregated facilities while starring for the Boston Celtics. Olympic track medalists John Carlos and Tommie Smith created an international furor with their black power salute at the 1968 Olympics in Mexico City, which hurt their subsequent professional careers.

In 1969 All-Star St. Louis Cardinal outfielder Curt Flood refused to accept being traded to the Philadelphia Phillies. He objected to being treated like a piece of property and to the restriction placed on his freedom by the reserve clause, which allowed teams to trade players without their having any say in the matter. Flood, an African American, considered himself a “well-paid slave.” With support from the players union, Flood sued Major League Baseball. In 1970 the US Supreme Court ruled against Flood, but five years later the reserve clause had been abolished and players became free agents, paid according to their abilities and their value to their teams.

Since the 1960s, a handful of athletes have challenged the political status quo. In the 1970s tennis great Arthur Ashe campaigned against apartheid well before the movement gained widespread support. In 1992 he was arrested outside the White House in a protest against American treatment of Haitian refugees. In the 1970s and 1980s tennis star Billie Jean King, followed by Martina Navratilova, spoke out for women’s rights and gay and lesbian rights.

In 2003, just before the United States invaded Iraq, Dallas Mavericks guard Steve Nash wore a T-shirt during the National Basketball Association (NBA) All-Star weekend that said “No War. Shoot for Peace.” Several other pro athletes—including NBA players Etan Thomas, Josh Howard, Adam Morrison, and Adonal Foyle, baseball’s Carlos Delgado, and tennis star Martina Navratilova—raised their voices against the war in Iraq.