The success of the Confederate forces at the battle of Manassas convinced many of the Southern volunteers that the objectives of the war had been accomplished, that the South was secure from further invasion, and they had done all that their country expected of them. President Davis and his military advisors knew otherwise and faced the daunting task of consolidating their victory and preparing for the longer war.

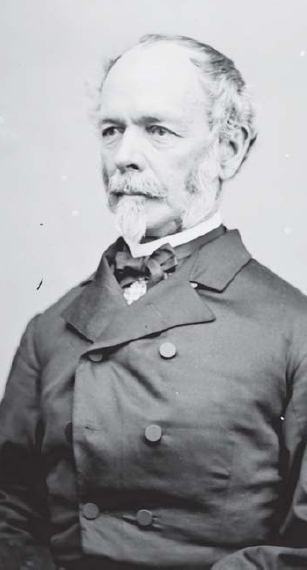

In his Narrative, General Joseph E. Johnston stated of First Manassas, “the Confederate Army was more disorganized by victory than that of the United States by defeat.” (LOC)

The Federal Army may have been temporarily disrupted by their defeat, but the North was not yet ready to concede anything to the South, and was still dictating the overall direction of the war. In May 1861, Lt. Gen. Scott had proposed his “Anaconda Plan,” calling for a blockade of all Southern ports and a simultaneous advance down the Mississippi River to cut the Confederacy in two and persuade the anti-Secessionists in the Southern States to rise up and reclaim their government. The plan was derided by the Northern firebrands, who thought it too passive and, particularly after Bull Run, demanded an all-out war effort by the North.

Lincoln also desperately wanted action, but first had to repair his shattered army. He turned to Maj. Gen. McClellan, who was a superb organizer who transformed the Union Army. His goal was to instill a confidence in that army that would enable it to heed the North’s battle cry, “On to Richmond.” Where he fell short was in leading his troops in the field.

Despite the Union commander’s faults, Johnston and Davis knew he would take the field eventually. A conference of the senior leadership of the Confederate Army at the end of September had persuaded Davis that a shortage of the basic requirements of an army, namely men and equipment, dictated a primarily defensive stance against the North, at least initially. Johnston felt that “the next important service of that army would be near the end of October, against the invasion of a much greater Federal army” than the one they’d fought in July.

As the months passed with nothing more than a series of small blunders by the North, like the badly bungled affair at Ball’s Bluff which led to Scott’s retirement, the preparatory actions continued. Jackson established his headquarters at Winchester on November 4. As the left wing of Johnston’s department his duties were straightforward: keep an eye on the enemy in the region, keep open the lines of communication with Johnston, and be ready to join the main army, as he had the previous summer, when Union forces began to advance.

“I find myself in a new & strange position here – Presdt, Cabinet, Genl Scott & all deferring to me.” McClellan to his wife Mary Ellen, July 27, 1861. (LOC)

Jackson yearned to go on the offensive. In October 1861 he proposed an invasion of Pennsylvania. “McClellan,” he said, “with his army of recruits, will not attempt to come out against us this autumn. If we remain inactive they will have the advantage over us next spring.” He concluded, “We ought to invade their country now, and not wait for them to make the necessary preparations to invade ours.” When his plan to “force the people of the North to understand what it will cost them to hold the South in the Union at the bayonet’s point,” was disapproved, he submitted a second proposal to advance on the Federal garrison at Romney in northwestern Virginia. This, Davis was willing to allow.

As Jackson was launching his Romney Expedition on January 1, 1862, Johnston was reporting an effective total of 57,337 troops within the Department of Northern Virginia. Of those, 10,241 were in the Valley District. Coincidentally, McClellan was reporting 183,507 present for duty in the Army of the Potomac, of which 16,000 were with Banks’s Division, responsible for the Shenandoah Valley region. Any disparity in troop strength did little to dissuade Jackson. He understood that the bulk of the Union troops was north of the Potomac, but the opportunity to attack the isolated garrison of 5,000 men under Brig. Gen. Benjamin F. Kelley at Romney was too good an opportunity to miss.

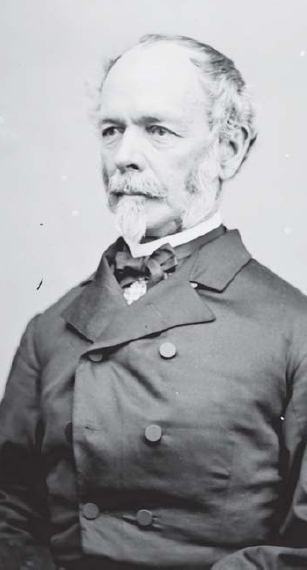

In the fall of 1861, Jackson proposed an invasion of the North through Romney, occupied by the 4th Ohio Infantry. From northwest Virginia, he would join with Johnston to take Philadelphia. (LOC)

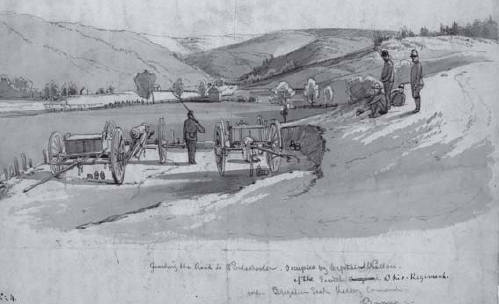

McClellan’s delays were ridiculed in the Northern press. This cartoon shows him with Uncle Sam before a playbill announcing, “Every day this week, Onward to Richmond, by a select company of star Generals.” (LOC)

Kelley’s men withdrew as Jackson approached. The weather was brutal and Jackson decided upon capturing the town to return to Winchester, leaving a detachment under Brig. Gen. William W. Loring, behind. He had hardly returned to the Valley when he received a letter from Secretary of War Judah P. Benjamin. “Our news indicates that a movement is making to cut off General Loring’s command; order him back immediately.”

As soon as Jackson had left Romney, the officers under Loring had filed a complaint through government civilian channels, with Loring’s approval, of Jackson’s handling of the Romney expedition. They maintained that they had been poorly used, and Romney itself held little strategic value. Jackson did as he was directed and then submitted his resignation. “With such interference in my command I cannot expect to be of much service in the field.” The fact that the order had come, not from his military superior General Johnston but directly from the civilian Secretary of War, induced Jackson to believe that his judgment was being called into question.

Jackson wrote to Johnston and Virginia governor John Letcher explaining his actions. Both men were well aware of Jackson’s abilities and persuaded him to withdraw his request. A potential crisis was averted, but the issue of civilian control of the military was one that would affect more than one officer during the Civil War.

McClellan had submitted his original plan of operations for all Union forces on August 4, 1861. He proposed an advance on all fronts, with particular emphasis on Nashville and Richmond, supported by operations down the Mississippi. Initially, Lincoln waited patiently for McClellan to put his plan into action. As fall dragged into winter, the President became increasingly anxious for McClellan to do something, anything. McClellan reassured him that he was getting close, but in December he fell ill and it wasn’t until mid-January that he was again ready to take up the issue of going on the offensive.

On January 20 Edwin M. Stanton was appointed Secretary of War in place of Simon Cameron. One of Stanton’s first acts was to direct McClellan to take immediate steps to reopen the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, which ran through the northern end of the Shenandoah Valley, and to readdress his plan for attacking Richmond. McClellan proposed sending his army “down the Chesapeake, up the Rappahannock to Urbana, and across land to the terminus of the railroad on the York River,” whereas Lincoln proposed a more direct overland attack.

Lincoln eventually complied with McClellan’s desires, with one critical caveat, that “no change of the base of operations of the Army of the Potomac shall be made without leaving in and about Washington such a force as, in the opinion of the General-in-Chief and the commanders of army corps, shall leave said city entirely secure.” In Lincoln’s mind, the security of Washington depended on leaving McDowell’s Corps within supporting distance of any enemy action against the Capital. McClellan was adamant that the success of his Peninsula campaign hinged on a simultaneous advance of his own forces up the Peninsula with McDowell’s advance overland via Fredericksburg.

At the end of February, McClellan traveled to Harper’s Ferry to observe Banks’s advance into Virginia to secure the reopening of the railroad. Johnston and Davis told Jackson that it was his job to do everything that Lincoln and McClellan most feared – tie up Union troops in the Valley, convince Lincoln to keep McDowell where he was, and ultimately slip away to join Johnston at Richmond and attack McClellan.

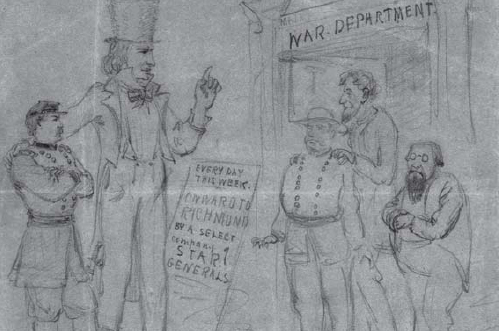

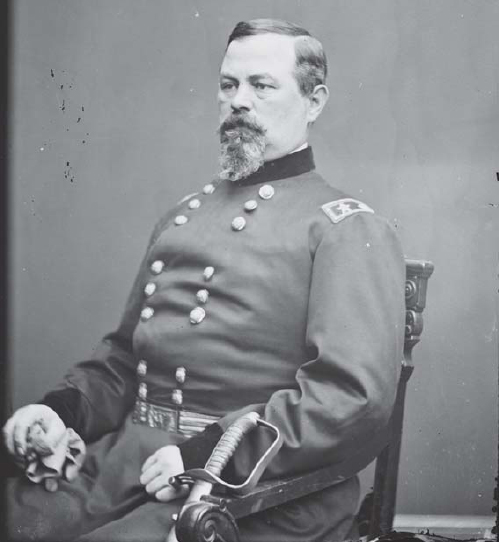

McDowell took the brunt of criticism for the Bull Run disaster. During the Valley campaign he became entangled in a tug-of-war between Lincoln and McClellan for the use of his corps. (LOC)