Lewis And Clark

An intelligent officer with ten or twelve chosen men... might explore the whole line [of the Missouri] even to the Western Ocean.

From President Jefferson’s confidential proposal to Congress in January 1801 that an expedition should be sent across the continent

***

To President Jefferson, the blend of geographical ignorance and tall-tales - rumors of prehistoric animals, a tribe of Welsh-speaking Indians, and, no doubt, mono-breasted Amazons - that came out from the mists of the continent’s vague interior was too tantalizing to be ignored. So for some years, quietly and without advertisement, he had been planning an expedition of exploration - regardless of who, at the time, actually claimed ownership of the unmapped vastness.

To this end, two years before that fortuitous transaction in Paris, he had selected a young army officer, Captain Meriwether Lewis, to be his private secretary. This was a disguise: Lewis was really being groomed as the leader of the projected expedition. Accordingly, he was sent off to various savants and scientists in Philadelphia for crash courses in navigation, surveying, botany and geology. He was instructed to read anything that had even the remotest bearing on the project being planned. There was not much.

Lewis would certainly have studied the recently published account of Alexander Mackenzie’s journey ten years earlier right across Canada to the northern Pacific. Both Lewis and his patron, the President, would have been worried by the last part of Mackenzie’s book in which he outlined British schemes for the far north-west. While predicting rich returns in fish and furs, he also forecast that the plans also had “many political reasons which it is not necessary here to enumerate”. This elliptical phrase added another purpose to Lewis’ assignment; he must get to the far Pacific to plant the new republic’s flag before the British. Elsewhere in Mackenzie’s account, Lewis would have been excited to read that the Scot claimed to have made his journey across most of the western part of the continent by paddling from one river or lake to the next with only a few intervening portages.

Lewis would also have learned that in 1792, Robert Gray, the first American to sail around the world, had discovered the mouth of a huge river (the Columbia) and deduced, from its size, that its headwaters must be far inland. Lastly, Lewis would have known that French fur men had, for several years past, been trading far up the Missouri. So the conclusion was obvious: a journey to the Missouri’s headwaters (wherever they were) should place an expedition, via a modest portage or two, within reach of the headwaters of Robert Gray’s Columbia. From there, surely, one would be able to float downstream to the Pacific. After that, it could not be far to China and the Indies. Helpfully, Jefferson suggested that if, on arrival at the far Pacific shore, the expedition found itself short of funds it should contact the American consul in Mauritius.

Even if the President had rather foreshortened ideas about global geography, his 2,000-word brief to his protégé was detailed and exact. “Your mission is to explore the most direct and practical water communication across this continent... make yourself acquainted with the names of nations... their language, traditions, monuments... their laws and customs... their diseases and remedies... the animals... the remains of any which may be extinct [Jefferson collected bones]... your observations are to be taken with great pain and accuracy... several copies... one to be written on the paper of the birch as less liable to damp... name a person who shall succeed you on your decease.”

Captain Lewis must have been glad when, eventually, he could say farewell to his demanding patron. He took the traditional route west: to Pittsburgh, then down the Ohio River and out onto the Mississippi. Presently, he was joined by an old friend whom he had asked to come as co-leader of the expedition: Captain George Clark.

By Christmas, 1803, they had established a base camp on the east bank of the Mississippi, just opposite St. Louis and near the mouth of the Missouri. They would have based themselves in St. Louis itself, but its French governor had not yet heard that his domain had just been bought by the United States. He thought the sale was so improbable that he would not take Lewis’ word for it.

The winter was passed in gathering stores and recruiting. Eventually, there were nearly 40 men in the party: soldiers, Kentucky hunters, French-speaking voyageurs with up-river experience, and Clark’s black servant, York. They would travel in the keel-boat which had brought Lewis down from Pittsburgh. She was nearly 60 feet long, had a small cabin aft, and was equipped with a large square sail and 22 oars; they also had a couple of large open canoes.

With 10 tons of stores aboard, they pushed off on 14 May 1804. “Proceeded under a jentle brease up the Missourie.” As the “brease” does not seem to have lasted, progress depended on their sweat - rowing, poling or, where possible, towing from the bank. They were plagued by “numerous and bad ticks and mosquiturs”.

After 10 weeks they had come only 500 miles. They tied up for a couple of days to “invite the Otteaus and Panies (Pawnees) to come and talk with us at our Camp”. At the meeting, presents were offered, and several chiefs were informed that as result of a recent “Change of Government”, they and their people were now subjects of the Great Father in Washington. The locals had no idea what all this meant but they willingly accepted the presents. And, because it seemed the obvious thing to do, Lewis called this meeting place Council Bluffs.

The site of that meeting is a few miles further upriver from today’s city of Council Bluffs. But no matter. You can stand in the main street of Council Bluffs and look across “the wide Missouri” to Omaha’s airport from where the jets go screaming off to San Francisco, Seattle, Salt Lake City, Chicago, New York... Incredibly, only 70 years after the expedition paused here, an iron railroad bridge would span the great river. You could then (with three changes) travel right across the continent, from New York to San Francisco Bay, from “sea to shining sea”, 2,800 miles, 10 days and $200. I mention this detail because, coming less than a lifetime after Lewis and Clark passed this way, it seems an excellent illustration of the speed with which the vast interior of the continent was tamed.

Incidentally, the locals call the river the “Mizzurah” - no final “ee”.

Going on, the expedition was encouraged to find that the river bent away toward the north-west; they optimistically reckoned that they were now paddling in the right direction - toward the Pacific. They also knew that they were now entering the country of the unpredictable Sioux.

As they feared, the Sioux were full of “rascally intentions”. Nevertheless, they thought it prudent to spend a few days with them. After all, it was just possible that the expedition might have to come back this way. There were peace pipes to be smoked, presents to be exchanged, and plate-size medallions to be hung round the necks of selected chiefs. In this last matter, Lewis and Clark were continuing a custom that the French had started more than 100 years earlier: first, to identify a few apparent leaders who seemed more amenable than the rest; then to present them with a badge of office. In this way they become the “official” chiefs through which the government could deal in any later negotiations. The system had worked well enough among the eastern tribes, where a hierarchical structure was more developed. But these tribes out on the plains did not work like that, and, down the following century, the system would cause endless aggravation to Washington’s would-be treaty-makers. For a start, the more tractable chiefs were often not the ones most respected by the tribe. Second, an agreement made with one group of chiefs was seldom regarded as binding by their rivals.

***

Even today, in any negotiation with the Sioux (particularly with the Oglala tribe), it is important to know that one is talking to the right people. Some years ago, I wanted to film a short sequence of “Native American” dancing and music at a summer festival on Pine Ridge Reservation, the homeland of the Oglala Sioux. I negotiated a day or two in advance with members of the Tribal Council. The questioning was quite tough and I had to explain to a suspicious audience that my documentary, being made by the BBC, did not have a moneybag sponsor, nor, when it was eventually transmitted, would it carry remunerative advertising. Eventually it was agreed that for $200 we could film for an hour. Willingly, I paid. A few days later we turned up at the festival somewhere in the back-country of the reservation. Entry was refused. I explained that our presence had been agreed - and paid for. I was told that the Tribal Council was made up of busybodies who had no jurisdiction over these proceedings and that I had been negotiating with quite the wrong people. Anyway, why should I be believed? “Never”, I was informed, “trust a white man.” Who was I to argue? Anyway, another $200 would be required. Maybe I was being ripped off, but given the way the Sioux have themselves been ripped off over the last 150 years, I knew that I was in no position to complain. My experience came as no surprise to those who think they know the Sioux. “So, what’s new?” was the general reaction.

In fact, though I did not know it at the time, I had naively run slap-bang into an enmity which had been developing between a dissident group and the Tribal Council. A few years later, this hostility was one of the causes of the second “battle” of Wounded Knee. We will come to that sad story...

***

As the expedition pushed on upstream it called on several other tribes until, in early November, it reached the country of the Mandan people. The river was beginning to freeze. So they tied up their boats, built a rough fort and prepared to snug down for the winter. They had come over 1,500 miles, and this was about as far as all but a very few whites had ever penetrated.

The Mandans were a more or less settled people who probably saw, in the expedition and its guns, some protection against their enemies, the marauding Sioux. And the expedition had callers: French-Canadian traders. One of them, Toussaint Charbonneau, had recently taken a young wife from among the Mandans; it is probable that the expedition leaders thought that, despite the fact that Sacajawea was only just 16 and pregnant, she would be useful to them. First, they knew that Indian war-parties never traveled with their women, let alone one carrying a papoose. So there was a fair chance that any roving Indians the expedition might meet would conclude that Sacajawea’s companions did not have any hostile intentions. Second, she was not a true Mandan, but had been taken five years earlier from a tribe called the Shoshone who lived away to the west. Now, the two Captains, thinking ahead, knew that when they eventually had to leave the river they might need horses. Sacajawea would be a useful interpreter and go-between. So it may well be that Sacajawea’s husband really owed his engagement to the fact that he had a potentially useful wife. As for her pregnancy, she would have the baby at least two months before the expedition moved on; Indian mothers were quite accustomed to traveling within a very few days of giving birth.

Of course, the piquancy of just one girl among so many men has been altogether too much for some people. The situation particularly appealed to the Victorians, who saw Sacajawea as a curvaceous, high-bosomed, wasp-waisted, dark-eyed Valkyrie with twinkling rings on her toes, a dagger in her belt, and feathers in her waist-long plaits. And, of course, Lewis or Clark or both fell in love with her. The unsentimental truth is that Sacajawea seems to have been a quiet and modest young woman who became a thoroughly useful member of the team and, yes, in time everyone became fond and caring towards her and her baby.

By late March the ice was melting and they were ready to go. On an afternoon in early April, they watched their keel-boat with its 14-man crew drift away downstream. It carried a cargo of specimens and reports for their patron in far-away Washington. Then they loaded their own small dug-outs (built during the winter) and the two larger canoes that they had brought with them.

For the next few weeks, they bent their heads against the stinging sleet and hail of the spring storms - they were in present-day North Dakota. Then, as the weather got warmer, there were clouds of midges and more of those “mosquiturs”. Details of all the creatures they met went down in the journals: grizzly bears, buffalo, antelope, rattlesnakes, cougar and, above all, beaver. Jefferson would be disappointed; he had hoped for mammoth elephants.

Jefferson was also going to be disappointed in the expedition’s failure to find any of those Welsh Indians. (There were also rumors of Israelite Indians and Chinese Indians, but about these Jefferson was more skeptical.) This beguiling piece of Celtic lunacy had its origins in the legends of a Prince Madoc, who was supposed to have led his people across the Atlantic hundreds of years before. Always, according to the tales, the Welshmen had inconveniently wandered off somewhere “more west”. A few years earlier, a single-minded Celt, John Evans, got as far as the Mandan villages looking for them. True, some of the Mandans were lighter skinned than most other Indians, and, yes, they built Welsh-looking coracles. But, no, they did not know what John Evans was talking about.

By early June they could see mountains on the western horizon. Then they came to a series of impassable cascades. These were the Great Falls of the Missouri. There was nothing for it but to drag the boats and all the stores around the rapids until they reached smooth water again. They must have been deeply frustrated. They had so hoped that, like Mackenzie away to the north 10 years before, they would have been able to make their way right across the continent with only a few short and easy portages.

The biggest boat was too heavy; it had to be left behind. For the other boats, they made crude rollers with logs. For day after day they pulled and pushed. As soon as one load had been taken forward, they had to make the 18-mile hike back to get another. It took three weeks.

Once back on the river, they paddled, poled and towed themselves as fast as they could manage. Soon, the river (they called it the Jefferson) became a mountain torrent; the canoes could go no further. Now it was urgent that they found the Shoshone - Sacajawea’s people - and traded for horses. Lewis and three others went ahead to try to make contact.

“After refreshing ourselves”, wrote Lewis on the third day of his trek, “we proceeded on the top of the dividing ridge from which I discovered immense ranges of high mountains still to the west of us with their tops partially covered with snow.” Lewis must have been devastated: he could see that there was now no possibility of a convenient portage to take them across to some river that would lead them easily down to the Pacific.

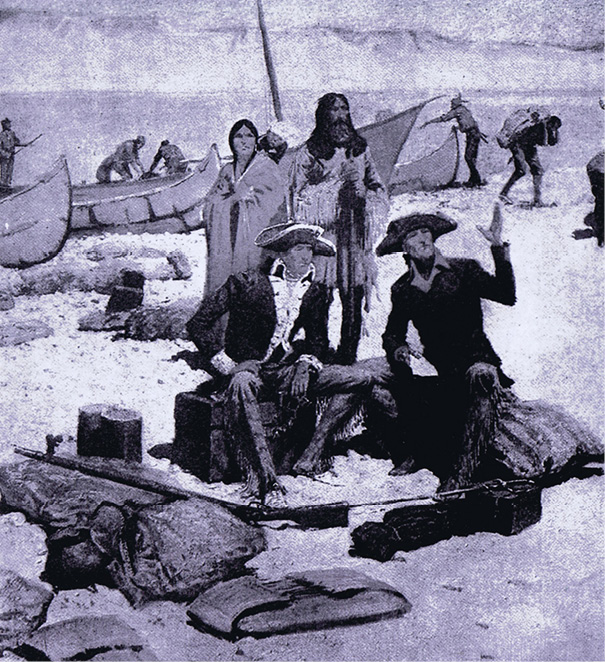

Sacajawea in another romantic reconstruction

***

I was sitting in the departure lounge at Salt Lake City waiting for a flight north to the town of Great Falls, to make preliminary arrangements for a film about the wheat harvest. On my knees was a large road atlas and it was turned to the double-spread of Montana; I was trying to work out how close the flight-path would go to the Lewis-and-Clark country at the head of the Missouri. Maybe the man waiting in the next seat thought I was trying to find some small town. Anyway, he said that he was from Montana and asked if he could help. Well, maybe he could. He doubted that we would fly quite that far west; we would miss those particular mountains by about 100 miles. But he was a western history “buff” himself and, being an executive with Western Airlines, he would ask the pilot when we got aboard. Then, while we were about it, how was “jolly old London”, and why not fly Club Class with him, courtesy of the airline? Thank you very much.

An hour later the aircraft seemed to bank slightly. My friend explained that there was no question of the pilot diverting by more than the smallest fraction from the airline’s normal routing, but he might, for a few seconds, drop the port wing slightly so that “we can get a better view”. It was one of those blue, mountain days when one can see for 100 miles or more. Somewhere ahead was Three Forks, and away off to the west, sliding under the wing, were the very foothills up which Lewis had struggled on Monday, 12 August 1805. On the farthest horizon, partially covered with snow, were what I reckoned to be the Salmon River Mountains, probably what Lewis could see from the crest of his windy ridge.

At 28,000 feet and close to 500 m.p.h. I did not learn much except an even greater wonder at the nerve of those first explorers; and that the Rockies stretched away forever, range after range. It was enough. I would not have missed it.

A few minutes later we were over the wheat country of the plains. Then we passed the broken water of the Missouri and landed at Great Falls. From my map I could see that the runway was just across the river from the place where the expedition put its boats back on the river after that 18-mile portage. I remember that, on leaving the aircraft, I was allowed to put my head round the door to the cockpit to thank the pilot for what might have been a slight divergence from his normal flight-path. “Well, we dodged over a little-bitty to the west”, and I’m sure he gave a wink, “’cause we figured on some clear-air turbulence to the east - and we always aim to give you folks a real smooth ride.”

“It was great. Thank you very much.”

“You’re welcome.”

***

As Lewis and his companions went on, they began to realize that the valleys and the streams had a westerly thrust to them. In geography and in history, they had crossed the continental divide. More prosaically, they were running out of food. Then, just when they were about to turn back, they came on four women. Two of them ran away. But an old woman and a young girl were too frightened or too slow to run. The white men tried to reassure them by sign language, and by giving them some beads and a small mirror. Suddenly, with a rushing of hooves, the explorers found themselves facing 60 or more warriors. Lewis put his gun on the ground and walked forward. The Indians sat their horses and watched; some fingered their bows. This was the most critical moment of the expedition so far. Then the old lady shouted; she seemed to be calling out that these strange pale beings had given her some presents. She ran across to show the beads. The Indians rode slowly forward. Perhaps the chief leaned down from his horse and touched Lewis to see what kind of man this was. It was enough.

“The men advanced and embraced me very affectionately in their way, which is by putting their left arm over your right shoulder, clasping your back, while they apply their left cheek to yours and frequently vociferate ah-hi-e, ah-hi-e, that is ‘I am much pleased, I am much rejoiced!’ We were all caressed and besmeared with their grease and paint till I was heartily tired of the national hug.” Given his luck, Lewis seems unreasonably grumpy.

They spent the night in the Shoshone camp where they were received with much dancing and mutual smoking of ceremonial pipes. But it took two more frustrating days of sign language before the Indians could be persuaded to go back to meet the rest of the expedition. When they reached the pre-arranged rendezvous with the main party, there was no one there. The Indians became very edgy, fearful of some treachery. Lewis was on tenterhooks lest they took off for some hiding place where he would never find them or their horses again.

Now comes the moment so beloved by all tellers of the expedition’s story, whether they are romantics or dry old realists. The Indians pointed to three distant figures coming up the river; Lewis recognized them as Clark, Charbonneau and Sacajawea. Slowly the three figures came on, unaware that they were being watched. Then Sacajawea must have seen them; she knew immediately that they were her own people and, scrambling forward, she embraced the chief. Lewis reports rather flatly that “Captain Clark arrived with the Interpreter Charbono and the Indian woman who proved to be the sister of the Chief; the meeting of these people was really affecting”.

The next day was Lewis’ 30th birthday. He spent it giving presents to the Shoshone. The main party had now come up. With no time for a rest, they hid their canoes and transferred their loads to a string of newly bartered horses. Then whites and Indians made their way back into the mountains. As they wound their way up, the whites questioned their guides, presumably through Sacajawea, about the best route to reach the great western river, the Columbia.

On one point the information was quite specific: the upper Columbia (in fact the tributary now called the Salmon) was impassable to any rafts. Nor would horses be able to find a footing on the sheer canyon walls. If this were true - and Clark set off to verify it while Lewis bartered for more horses - it could be a disaster.

Clark was away for four days. He found that the river was everything that the Indians had claimed. Now, not only was there no hope of making a quick passage through the mountains, but gone too was the chance of establishing a workable route across the continent to the Pacific. Perhaps there was some easier way that they had missed? Anyway, with winter coming, they would have to scramble forward as fast as they could.

They said goodbye to their Shoshone friends. The next few weeks were the hardest of the whole journey. Often they had to climb high up along the ridges in the wind and clouds, with only the mistiest idea of where they were going. They were always cold, and damp. They could find no game, so they ate dog. Their clothing was quite inadequate, their boots and moccasins were ripped and torn. At night, there was never enough dry wood to build a fire; anyway, they were usually too tired to try. Most of them had dysentery at one time or another, either that or an aching hunger. This was no way to reach the Pacific.

Coming down, at last, into the beautiful and warmer valley of the Bitter-root, they met Indians again. These were the friendly Flatheads. They paused long enough to regain some strength (they called the place Travelers’ Rest) and to buy more horses. They also transcribed many words of the local language. “They appear to us as though they had an impediment in their speech.” Welsh, perhaps? Anyway, Lewis, conscientious as ever, was taking no chances and noted down “the names of every thing in their Language, in order that it may be found whether they Sprang or origenated first from the welch”.

A few miles beyond the Flatheads, they climbed into more mountains, more snow, more dysentery, more frostbite. Often they only managed to make 9-10 miles in the day, but the wonder is that, somehow, they kept going at all. Perhaps Sacajawea had something to do with it. If a 16-year-old mother with a papoose on her back could take the hardships... It was during this scramble over the Lolo Pass that the expedition really came to admire the uncomplaining spirit of the girl. They had grown fond of the baby swaddled on her back, whom they called Pompey; it meant “little chief” in his mother’s language.

At last they limped down into the easier valleys of the Pierced Nose Indians (the Nez Percé). The Indians told them that they were only a few days from a large river. It turned out to be the Clearwater and, on the evidence of the salmon they could see, they reckoned that it must eventually flow into the Columbia and thence into the Western Ocean. So now they built another flotilla of canoes, and left their horses with the Nez Percé. The worst, they hoped, was now behind. They reckoned that they had come 300 miles since they had hidden their boats back on the Jefferson; it had taken 8 weeks.

Today, in summer, the map shows that one can drive the whole distance from the Jefferson to the Clearwater in about 5 hours. I have not made the journey (one day perhaps), but the road winds through the same mountains and over the same passes; it follows the expedition’s route, sometimes exactly, always within a few miles. Dynamite and bulldozers have made the difference. True, you will need to fit chains to your tires in autumn - if the road is still open. In winter it is firmly closed: both the Lost Trail Pass and the Lolo Pass are blocked by snow and ice. All this you can learn from any worthwhile road map. And you can see too that the Flatheads still have their lands, a reservation now, just to the north of Travelers’ Rest.

On water once more, the party’s morale revived. They had no accurate way of knowing how far they were from the Pacific. In fact, they had nearly 300 miles to go. But now, traveling with the current, progress was much faster. Sometimes, round the “smokey” evening fire (smokey to drive off the “mesciters”?) they even found time to relax and laugh again: “After dark we played the fiddle and danced a little.”

When they came out onto the Columbia, they were amazed at its size; it was even wider than the Missouri at St. Louis. Now they paddled easily toward the sea on the Great River of the West; it had been flowing through Lewis’ mind ever since he had first read the accounts of Mackenzie and Gray. But... if only there were an easier way across or around those cursed mountains.

Now the river broadened to nearly a mile, and the Indians hereabouts, the Chinooks, had canoes larger than any they had yet seen. Then they met a chief who kept repeating a phrase someone deciphered as “son-of-a-bitch”. A day or two later they came up with another chief who wore a scarlet coat and carried a sword. It began to rain. The dug-outs dipped to waves. They paddled on. Now gulls skimmed the boats, and the river grew to an estuary so wide that they could hardly see the other shore. The water became too salty to drink; the wind blew damp and raw; the beaches on which they camped each night showed the flotsam line of tides. Yet they still had not reached the sea.

For the next three days they took a terrible battering from gales which, blowing up the wide and unsheltered estuary, almost swamped their boats. Then one morning they saw far ahead a line of breakers where the “great Pacific Octean” pounded across the bar. It was 7 November 1805. The pathfinders of the prairies and the mountains had come at last to that “which we had been so long anxious to See”. In 18 months they had trekked 2,000 miles. In elation, they must have felt like Columbus when he first made landfall in his imagined Cathay. But, unlike him, they had some idea of where they were and what they had done. More or less.

“Ocian in view!” noted Clark. “Oh, the joy!”

***

Conscientious as ever, the two Captains had already decided that there were too many questions of geography on which they had failed. So even if a ship did come into the Columbia and offer them passage home, they would have to refuse. They would have to go back the hard way in order to fill in the gaps. But there was no point in starting yet; the high country would be impassable with winter snow. So they chopped down some trees and knocked together some rude shacks; they ran up the flag and called the place Fort Clatsop - after the thieving local tribe. From November to April, the coast of what, today, we call the Pacific North-West can be a very wet place indeed: day after day, the sodden winds blow in from the sea. The expedition’s journal tells that, in five months, it stopped raining for just twelve days. Even then, everything dripped.

Inside the fort, they were out of liquor, tobacco and salt. Outside, the opportunities for R’n’R were limited. A few of the more energetic souls ambled off to a nearby establishment run by a Clatsop matron and her six “nieces”. One of the nieces sported a tattoo which read “J. Bowmon”. So, in more ways than one, someone had already been here. The Captains disapproved of these goings-on, but on practical rather than moral grounds: there was the problem of payment. They were going to need all the trade goods they still had, to “pay” the various tribes during their return journey. In the end, they handed out a few colored ribbons and hoped for the best.

Not surprisingly, they all grew heartily sick of Fort Clatsop. In spring, as soon as the rains eased, they got ready to move. Before going, they carved their names on a few trees, raised more flags and handed out proclamations to the natives. While all this undoubtedly had an element of “Kilroy Was Here”, it was also part of the ritual of declaring to any subsequent passers-by that these parts were now formally claimed by the United States. On such very slender assertions of ownership, the nation was to become more than merely argumentative with the British three decades later.

On 23 March 1806, they abandoned Fort Clatsop and headed east. Four weeks later, when they reached the easy-going Nez Percé, they learned that the snows were still far too deep on the passes ahead; they would have to wait 30-40 “sleeps”. This enforced idleness was infuriating to the Captains, because there was so much to be done once they got beyond those mountains. But for everyone else, the delay in the spring sunshine of the high country must have been a golden time. The longer they stayed, the more they appreciated the hospitality of their hosts. They were given horses for food without mention of payment; they learned enough of the language to ease the monotony of only speaking to each other. That skill must have been handy when fraternizing with the younger of their hostesses. Indeed, after a few weeks, several of the explorers were quite ready to quit exploring. Apparently, even today, it is still a point of pride among a few families in that tribe to claim descent from those times; some even suggest that Captain Clark might be their five-times-great grandfather. There is no allusion to this possibility in the Captain’s journal.

When the expedition eventually pulled itself together to move on, it had spent seven contented weeks on the Clearwater.

Now, each man had a horse to ride and a pack-horse to lead. For five days they scrambled up, down, and along the ridges. On the sixth day, almost before they knew it, they were coming down to the warmth of the valleys again, to the comfortable place that earlier they had called Travelers’ Rest. Now, the plan was to split into three different parties for the next six or seven weeks, so that they could cover more ground in searching for a better route through the mountains.

Lewis reckoned to take six men directly east to look for an easier line back to the Great Falls of the Missouri. Meanwhile, Clark would take the rest of the expedition off to the south, to the place where, the year before, they had left their canoes and their stores. A part of this group would then take the re-loaded canoes directly downriver to the Great Falls, while Clark would try to find the headwaters of the Yellowstone River. If he and his small party succeeded, they would build a raft and float 400 miles down the Yellowstone until it flowed into the Missouri. There, at the junction of the two rivers, the three different parties would rendezvous in about six weeks’ time.

Astonishingly, the plan worked just as they had hoped.

***

Halfway down the Yellowstone there is what my guidebook mundanely called “a point of interest”. Without stretching things, the writer might have been more enthusiastic. He or she is referring to the one and only “in situ” remnant that, today, one can see of the whole long expedition. Three weeks into Clark’s raft journey down the Yellowstone, he noticed a massive sandstone outcrop half a mile or so from the river. He pulled in to the bank; he scrambled halfway up the outcrop and, in a looping script several inches high, he carved his name: Wm Clark July 25, 1806. “I marked my name and the day of the month and the year.” Today, one climbs 100 feet or so up a series of steep wooden stairways to reach a small platform. From there, one looks across a gap of about 12 feet to this simple piece of graffiti. It is guarded by a thick panel of plate glass. Clark called the whole outcrop Pompey’s Tower. Perhaps, as Clark left his mark, Pompey sat on his mother’s hip and watched from below. One would like to think so. Today, the place is known as Pompey’s Pillar. The afternoon I was there, I had the whole place, including the National Parks Visitors Center at the base of the cliff, entirely to myself - time and peace to wander and wonder. And to be not a little moved.

***

Three weeks after he had “marked” his name, Clark and his small party arrived at the junction of the Yellowstone with the bigger Missouri. He was ahead of schedule, so he settled down to wait for Lewis and his party. They came in just two days later. They were full of a narrow escape, when they had bumped into a small party of hostile Blackfeet. In getting away, they had killed two Indians. So, fearful that the remaining Blackfeet would summon a very much larger group of their fellows and come after them, Lewis and his men had just made a forced ride of over 100 miles in the previous 24 hours.

Now that the whole expedition was together once again, the fiddle came out, and they “went to dancing” around their cooking fires. Then, extraordinarily, just as they were pushing off downriver, they met two white men coming the other way. Dickson and Hancock were the first whites that the expedition had seen since leaving the Mandan villages 16 months before. They were the forward scouts of an extraordinary army of trapper-adventurers who, over the next 30 years, would beaver their way into every valley and over every pass of the western mountains.

The news the two newcomers brought from downriver was discouraging. The Mandans were feuding with the Aricara; the Minnatarees were squabbling with each other, and the Sioux were being bloody-minded toward the world in general. The expedition would have to run this complex gauntlet.

Before they paddled on, the two trappers asked if anyone could be spared from the expedition to join them as a partner and guide. John Colter was keen to go, and asked for his discharge; perhaps he was one of those people who prefer the dangers of the wilderness to the comforts of civilization. Anyway, he collected his few belongings and headed back west again with his newfound companions. But we will meet him again, for John Colter was now taking his first steps towards becoming his own special legend.

When the expedition arrived at the Mandan and Minnetaree villages, the inhabitants were only too happy to see the white men again; they represented protection against their enemies. Charbonneau announced that he and his wife wanted to stay with the Mandans, where they had started. So please, could they have their wages, $500 for the last 17 months? Clark wanted to take Sacajewea’s young Pompey, of whom he had become very fond, on to St. Louis for a white man’s education. His mother said that perhaps she would bring him when he was a little bigger. After all, he was not yet fully weaned. They gave one of their guns to a local chief, “to ingratiate him more strongly in our favor”. Then they pushed off. One hopes that the Charbonneau family came down to the bank to wave goodbye.

Now there were only 1,500 miles to go. With the current behind them, they could make 50 miles a day and hardly raise a sweat. In the afternoons, the sun “warmed our backs”. But, in the evenings, as always, “the mosguetors were excessive troublsom”. (Of the two Captains, Clark was the more inventive speller.) They paused several times for diplomatic meetings with various tribes. But when they came to the Sioux, they drifted past with their weapons levelled. The Sioux pranced about on the bank and shouted an invitation for the expedition to step ashore, so that they could all have a good fight. “We took no notice.”

As they went on, Lewis and Clark must surely have felt some pride in what they had done. By their leadership and judgement, they had not only held their men together under the greatest hardships, but they had forged them into an extraordinarily efficient “Corps of Discoverie”. In the whole long journey they had taken only two lives - those two Blackfeet. Even then, it had been “take or be taken”. Above all, they were fortunate in each other; never once had they had a serious disagreement. So, it is entirely appropriate that in all the subsequent histories, one name is hardly ever mentioned without the other. Captains Lewis and Clark were a most remarkable pair.

There were more traders on the river than there had been two years before. Every few days the expedition would sight a new party and, to a shouted welcome, pull over to a sandbank and talk. The traders would have been astonished to see them; the whole party had long been given up for lost. Indeed, the river-men had been specially asked by President Jefferson to try to find out what had happened. Even to these hardened river-traders, the men who now clambered out of their canoes and waded across to ask for news of home must have seemed as if they had come back from the dark side of the moon. Burnt as brown as any Indian, they would have had a way of standing, talking and laughing among themselves which would have marked them as men who had been alone together for a very long time. To those other men, so lately come from “civilization”, everything about this brotherhood must have been intriguing: their ragged but serviceable clothes, their questions, their stories, their music and songs, their jokes and ribaldries, even the Indian patois they sometimes used among themselves. They had been away for over two years.

Five weeks after leaving the Mandans, the expedition’s flotilla steered out of the Missouri onto the Mississippi. A few more miles and they could see St. Louis - now under the American flag. After all that they had been through, their diaries for Tuesday 23 September, 1806 are marvelously matter-of-fact. “12 o’Clock”, wrote one of the Sergeants, “we arrived in Site of St Louis, fired three rounds as we approached the Town... then the party all considerable much rejoiced that we have the Expedition Completed and now we look for boarding in Town.” So, they were back to the mundane reality of civilization: looking for lodgings. Sergeant Gass concludes, “We were received with great kindness and marks of friendship by the inhabitants, after an absence of two years, four months and ten days.” Perhaps, for the time being, that was all that was worth saying. They seem to have been men of no recognizable pretensions.

And what of Sacajewea and young Pompey? Captain Clark wrote repeating his earlier offer to educate the lad. He even offered, if the family came down to St. Louis, to see Charbonneau set up as a small trader or farmer. In due course, the family arrived. Clark kept his promises. He looked after the growing boy and made himself responsible for his education. Later, while still in his teens, Pompey met the touring Prince Paul of Wurtemburg; he must have been a personable lad because the Prince took him back to Europe. By the time Pompey returned to the United States it is said that he spoke at least three languages. Sadly, other than working for a time as a guide, he then seems to disappear. His mother too poses a mystery. Most histories report her dying of “the bloody flux” while still a young woman, somewhere in what is now North Dakota. But to this day the Shoshone people, her people, insist that she lived to be over 90 and is buried on their reservation in western Wyoming. Her gravestone is there for all to see.

The fact is that Lewis and Clark’s expedition had not found an easy or practical route to the Pacific shore or beyond to China; they had not discovered an obvious path for settlement; they had not laid an indisputable claim to new lands. But they had been to the Farthest Beyond, and returned; that was their achievement. In time, when the news spread, it would add immeasurably to their young nation’s self-confidence and knowledge of itself. From now on, Americans would come to know that, despite all the difficulties, the journey right across the continent to the other ocean could be made - had been made. In time, other Americans, travelling by other routes, would be spurred to go themselves. Most of the continent was theirs - if they could take it. In the end, surely that was what mattered about Lewis and Clark; that was their achievement.

I received, my dear sir, with unspeakable joy your letter of Sep 23 announcing the return of yourself & your party in good health to St Louis.

A letter from President Jefferson to Captain Lewis